Tax on 'Ghost Income'? Japanese Supreme Court Allows Refund for Uncollectible Vested Rights

Date of Judgment: March 8, 1974

Case Name: Claim for Unjust Enrichment (昭和43年(オ)第314号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

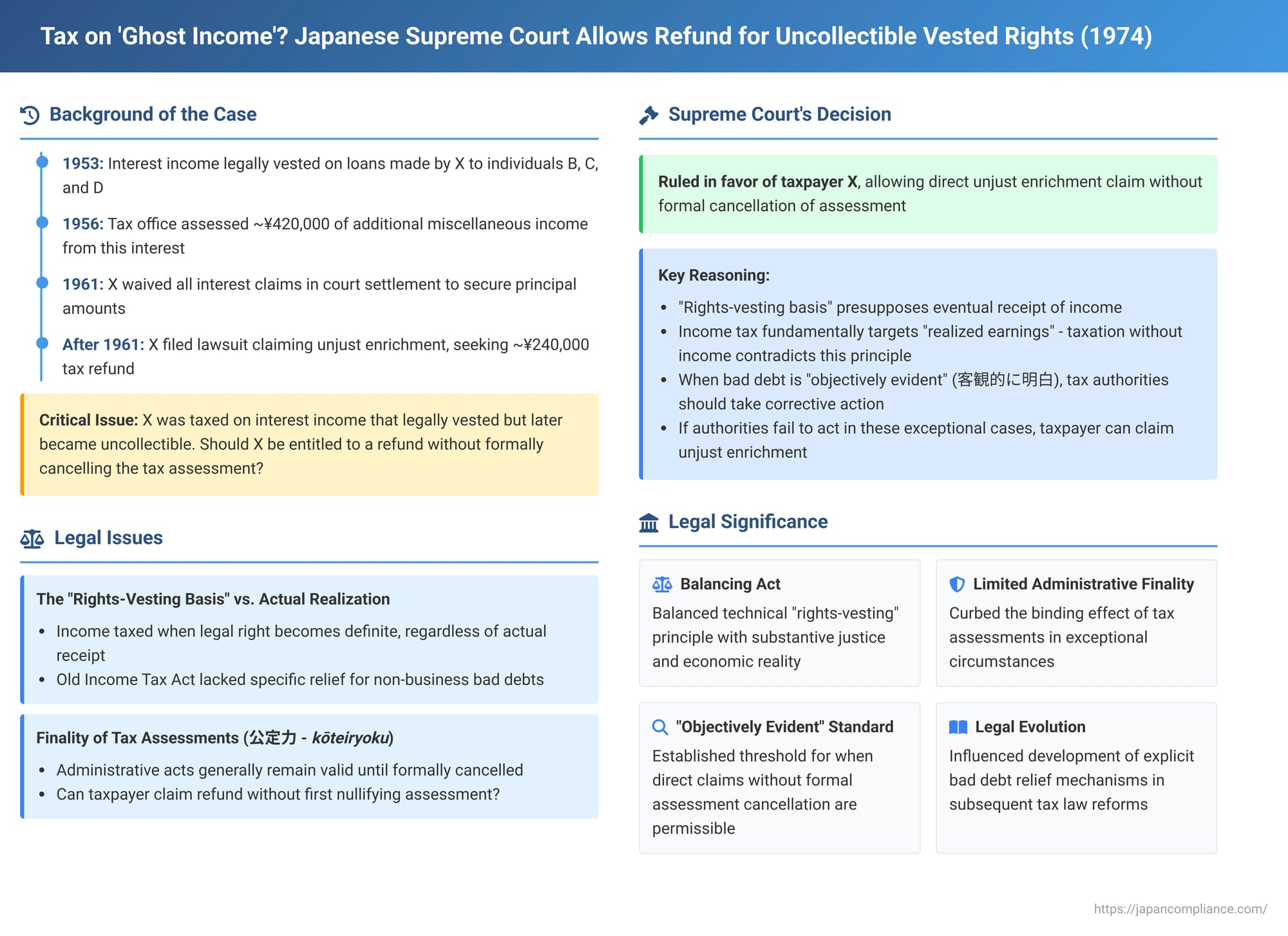

In a significant judgment delivered on March 8, 1974, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed a fundamental issue of fairness in income taxation: what happens when a taxpayer pays income tax on income that, although legally "vested" at one point, subsequently becomes uncollectible? The case concerned interest income assessed under the old Income Tax Act, which lacked specific relief provisions for bad debts arising from non-business activities. The Court, emphasizing principles of justice and fairness, allowed the taxpayer to recover the tax paid on this "ghost income" through a direct claim of unjust enrichment against the State, even though the original tax assessment remained formally uncancelled.

The Uncollectible Interest: A Taxpayer's Predicament

The plaintiff, X, was an individual taxpayer. In November 1956, the head of the A Tax Office issued a corrective income tax assessment to X for the 1953 tax year. This assessment increased X's total income by adding approximately ¥420,000 in miscellaneous income. This miscellaneous income amount was derived by applying a standard income rate to the total sum of:

- Interest and damages that had accrued during 1953 on loans X had made in 1952 to individuals B, C, and D (D was C's father; upon D's death, his rights and obligations were inherited by C and others).

- Interest and damages that had accrued during 1953 on other loans X had made to B et al. in that same year.

The income tax resulting from this corrective assessment was subsequently collected from X by the tax authorities through tax delinquency procedures.

X had initially secured these loans by obtaining mortgages on real estate owned by C and D. However, disputes later arose concerning these mortgages, and X faced a significant risk of losing both properties as security. Faced with the prospect that even the principal amounts of the loans might become irrecoverable, X entered into a court-mediated settlement with D's heirs in July 1961. As part of this settlement, in exchange for the debtors acknowledging the existence of the principal loan amounts, X agreed to waive all his claims for the accrued interest and damages related to these two loans—the very interest and damages that had formed the basis of the ¥420,000 miscellaneous income assessed to him for 1953.

Following this waiver, X asserted that the previously assessed miscellaneous income of approximately ¥420,000 had effectively become a bad debt and was uncollectible. He argued that, as a result, he had been taxed on income that never actually materialized. Consequently, X filed a lawsuit against the State (Y), claiming unjust enrichment. He sought a refund of approximately ¥240,000, representing the portion of the income tax and underpayment penalties he had paid that was attributable to this now-uncollectible miscellaneous income. It is important to note that this lawsuit was filed while the original 1956 corrective tax assessment remained formally in effect and had not been cancelled or amended by the tax authorities.

The lower courts (Tokyo District Court and Tokyo High Court) both ruled in favor of X, ordering the State to refund the claimed amount. The State then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Challenge: "Rights-Vesting," Bad Debts, and the Finality of Tax Assessments

The case presented a significant legal challenge under the old Income Tax Act (Law No. 27 of 1947, prior to its 1962 amendment by Law No. 44 of 1962). The core issues involved:

- The "Rights-Vesting Basis" (Kenri Kakutei Shugi): The prevailing principle for income recognition under the old Income Tax Act was the "rights-vesting basis". This meant that income was generally considered realized and subject to tax in the year the legal right to receive that income became definite and unconditional, regardless of whether the cash had actually been received by the taxpayer. X's interest income had been assessed on this basis.

- Subsequent Uncollectibility (Bad Debt): What happens if income, taxed upon the vesting of the right to receive it, subsequently becomes uncollectible? The old Income Tax Act provided a mechanism for deducting bad debts as necessary expenses if they arose in the context of business income. However, it lacked specific provisions for relief when non-business income, such as the interest income in X's case, became uncollectible.

- Finality of Tax Assessments (Kōteiryoku): A fundamental principle in Japanese administrative law is the "public force" or "binding effect" (公定力 - kōteiryoku) of administrative acts. This means that an administrative decision, such as a tax assessment, even if potentially flawed, is generally treated as valid and binding unless and until it is formally cancelled or revoked through prescribed administrative appeal procedures or a specific type of administrative lawsuit (an action for revocation). X had filed an unjust enrichment claim, which is a civil action, without first having the original tax assessment formally nullified.

The State argued, in essence, that the original tax assessment was legally valid when made (based on the then-vested right to interest) and remained so. Therefore, the tax collected under it had a legal basis, and no unjust enrichment could arise unless the assessment itself was first cancelled through the proper administrative or administrative litigation channels.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Justice and Fairness Demand Correction

The Supreme Court dismissed the State's appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' decisions that ordered a refund to X. The Court's reasoning navigated the tension between the formal "rights-vesting basis" of taxation, the finality of administrative acts, and the fundamental principles of fairness and justice in taxation.

The Court's key points were:

- "Rights-Vesting Basis" Presupposes Eventual Receipt: The Supreme Court acknowledged that the old Income Tax Act indeed adopted the "rights-vesting basis" for income recognition. However, it critically clarified the underlying rationale and limits of this principle. The Court stated that adopting this principle was a "technical consideration from a tax collection policy standpoint" (徴税政策上の技術的見地から - chōzei seisakujō no gijutsuteki kenchi kara). It was designed to prevent taxpayers from arbitrarily deferring taxation by delaying the actual receipt of income and to ensure a degree of fairness and predictability in tax assessment. However, the Court emphasized that the rights-vesting basis inherently "presupposes that the right will subsequently result in actual payment" (権利について後に現実の支払があることを前提として - kenri ni tsuite nochi ni genjitsu no shiharai ga aru koto o zentei toshite). It is essentially a standard for determining the timing of income attribution, not a definitive statement that tax is due regardless of ultimate realization.

- Taxation Without Realized Income is Fundamentally Flawed: The Court stressed that income tax is fundamentally a tax on "income brought about by realized earnings and expenses" (究極的には実現された収支によってもたらされる所得について課税するのが基本原則 - kyūkyokuteki ni wa jitsugen sareta shūshi ni yotte motarasareru shotoku ni tsuite kazei suru no ga kihon gensoku). If a monetary claim, having been taxed upon the vesting of the right to receive it, subsequently becomes uncollectible due to a bad debt, the very premise of that taxation is lost. This results in "taxation where there is no income" (所得なきところに課税 - shotoku naki tokoro ni kazei), a situation that inherently demands some form of correction. Such correction is a "corollary" or "reverse-side request" (反面としての要請 - hanmen toshite no yōsei) of adopting the rights-vesting basis.

- Status of the Original Tax Assessment: The Court clarified that an initially valid and lawful tax assessment does not retroactively become illegal or void merely because a subsequent event (like a bad debt) makes the underlying income uncollectible. However, if the tax authority, despite the premise of taxation being lost due to the bad debt, continues to exercise its collection powers based on that original assessment, or retains taxes already collected, such action would "not only contravene the essence of income tax but also create an unwarranted imbalance in relief measures" (所得税の本質に反するばかりでなく...いわれなき救済措置の不均衡をもたらす - shotokuzei no honshitsu ni hansuru bakari de naku...iwarenaki kyūsai sochi no fukinkō o motorasu) compared to situations where bad debts from business income were deductible. The Court found it "unthinkable that the law would condone such a result."

- Ideal Corrective Measures vs. Taxpayer's Direct Claim in Exceptional Cases:

- The Supreme Court noted that the most appropriate way to rectify such a situation would be for the tax authority itself to take corrective action. Once a subsequent bad debt becomes apparent, the tax authority should assess the existence and amount of the bad debt, recalculate the taxable income for the original year (by effectively deeming that the income corresponding to the uncollectible amount never existed for that year), and then cancel or amend all or part of the original tax assessment. If tax has already been collected, the overpaid portion should be refunded to the taxpayer. (The Court pointed out that subsequent amendments to the Income Tax Act, such as the former Article 10-6 and Article 27-2, had introduced such formal corrective mechanisms). The tax authority is "legally expected and required" (hōritsujō kitai sare, katsu, yōsei sareteiru) to take such corrective measures.

- However, the old Income Tax Act applicable to X's case lacked provisions granting the taxpayer a specific right to demand such corrective action if the tax authority failed to act.

- Given this lack of a specific statutory remedy for the taxpayer to compel correction, and considering that the reasons for entrusting tax assessment to the tax authorities are primarily technical and administrative complexity, the Supreme Court carved out an exception: If the occurrence of the bad debt and its amount are "objectively evident" (客観的に明白 - kyakkanteki ni meihaku) to the extent that there is no "rational necessity for reserving the power of recognition and judgment" (認定判断権を留保する合理的必要性が認められない - nintei handan-ken o ryūho suru gōriteki hitsuyōsei ga mitomerarenai) to the tax authority, and yet the tax authority fails to take corrective action, then requiring the taxpayer to simply bear the burden of the original taxation would be "grossly unfair and contrary to the principles of justice and fairness" (著しく不当であつて、正義公平の原則にもとる - ichijirushiku futō de atte, seigi kōhei no gensoku ni motoru).

- In such exceptional cases, even without a formal correction of the assessment by the tax authority, the authority (or the State) can no longer assert the validity of the original tax assessment against the taxpayer to the extent of the uncollectible amount. Consequently, the State cannot collect further tax based on that portion, and any tax already collected on it is deemed a benefit lacking legal cause and must be returned to the taxpayer as unjust enrichment.

- Application to X's Case: The Supreme Court found that in X's situation, the subsequent bad debt (the uncollectibility of the interest income) and its amount became "objectively evident" through the court settlement in which X waived the interest claims. There was no rational need for the tax authorities to reserve further judgment on this established fact. Therefore, the tax collected on this unmaterialized interest (¥243,315) was an unjust enrichment for the State and should be refunded to X.

Key Legal Principles and Implications

The Supreme Court's 1974 judgment was a landmark decision that profoundly impacted the understanding of income tax principles and taxpayer remedies in Japan:

- Balancing "Rights-Vesting" with Substantive Justice: The ruling demonstrated a crucial balancing act. While upholding the technical "rights-vesting basis" for income timing, it underscored that this principle cannot lead to the substantive injustice of taxing income that ultimately never materializes. The fundamental nature of income tax as a levy on actual economic gain was prioritized.

- Circumscribing the "Public Force" (Kōteiryoku) of Tax Assessments: This case is a leading example of the judiciary limiting the otherwise strong binding effect (kōteiryoku) of administrative acts like tax assessments. It established that subsequent, objectively verifiable events that fundamentally undermine the basis of an initial (and otherwise valid) assessment can, in exceptional circumstances, allow a taxpayer to seek direct restitution via an unjust enrichment claim without first having to go through the potentially lengthy and uncertain process of formally cancelling the original assessment through administrative litigation.

- The "Objectively Evident" Standard: The requirement that the subsequent bad debt be "objectively evident" and leave no rational need for further tax office discretion is a critical threshold for this exceptional remedy. This standard serves to limit purely subjective claims by taxpayers and prevents widespread collateral attacks on tax assessments.

- Evolution of Bad Debt Relief in Tax Law: While this judgment addressed a specific gap in the old Income Tax Act, subsequent tax reforms in Japan have introduced more explicit statutory mechanisms for taxpayers to seek relief or make adjustments when accrued income later becomes uncollectible (e.g., through provisions for bad debt reserves, or rules for correcting income in later periods). These later legislative developments have reduced the necessity for taxpayers to rely directly on the type of unjust enrichment claim sanctioned in this specific historical context. However, the underlying principles concerning the limits of administrative finality in the face of manifestly unjust outcomes remain jurisprudentially significant. Legal commentary has extensively debated the theoretical underpinnings of this decision, exploring how it reconciles the finality of tax assessments with the principles of unjust enrichment, particularly when post-assessment events negate the economic premise of the original tax.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1974 decision in this case was a pivotal moment in Japanese tax jurisprudence. It affirmed that, under the old Income Tax Act, principles of justice and fairness could, in exceptional circumstances, allow a taxpayer to recover taxes paid on income that was initially recognized based on a "vested right" but subsequently became definitively and objectively uncollectible. By permitting a direct claim for unjust enrichment against the State without requiring a formal cancellation of the original tax assessment, the Court provided a crucial remedy against what would otherwise be "taxation without income." While later legislative reforms have provided more specific pathways for addressing such situations, this judgment remains a testament to the judiciary's role in ensuring that the technical application of tax rules does not lead to results that are fundamentally at odds with the core principles of fairness and the economic reality of income realization.