Tax Law and Trust: A Balancing Act – The 1987 "Blue Return" Case

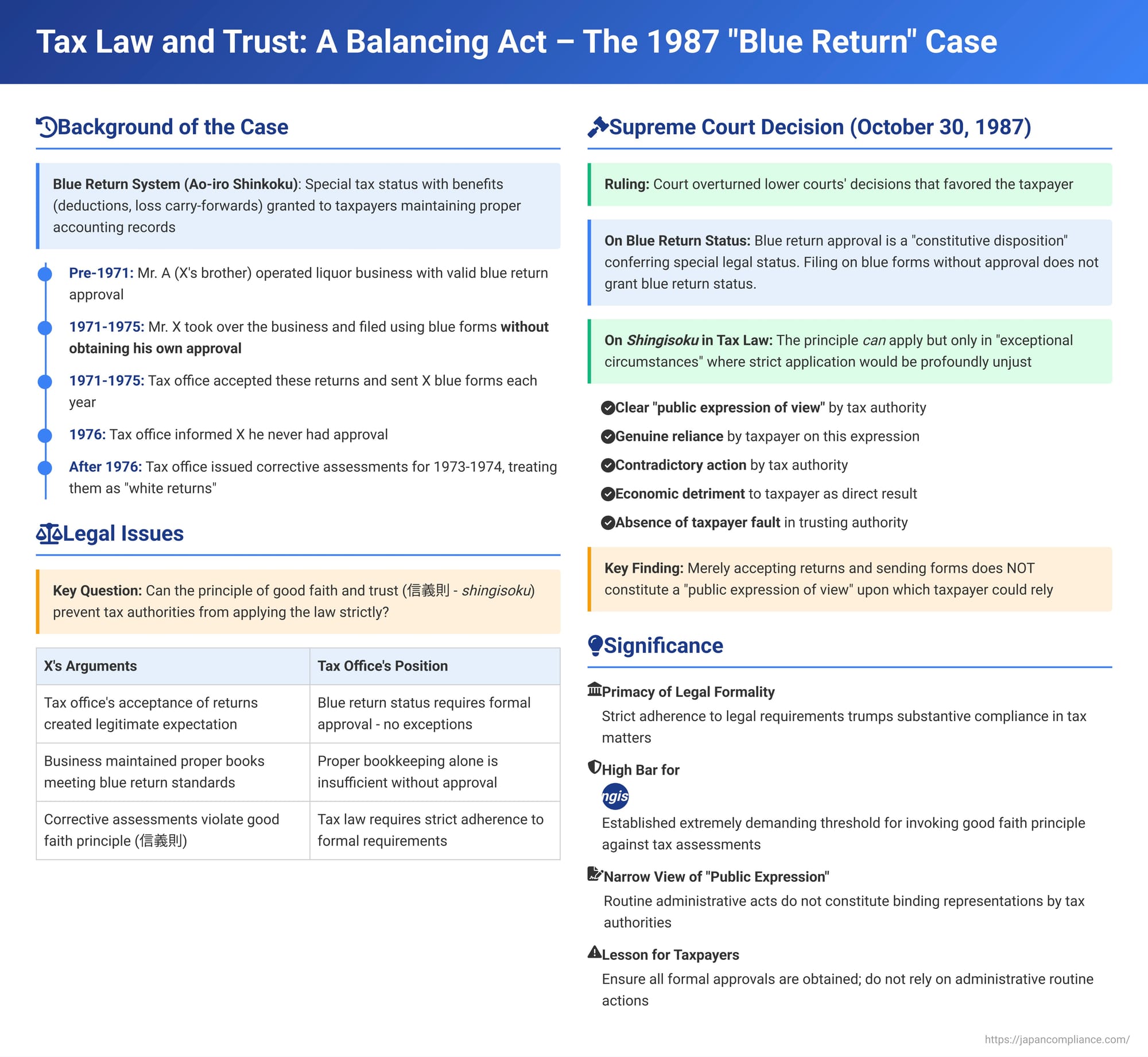

In the realm of taxation, a constant tension exists between the strict application of tax laws, designed to ensure fairness and predictability, and broader legal principles like good faith and trust (信義則 - shingisoku). Can a taxpayer rely on the tax authority's actions, even if those actions are later found to be inconsistent with formal legal requirements? A significant Japanese Supreme Court judgment delivered on October 30, 1987, grappled with this very issue in the context of Japan's "blue tax return" system, setting a high bar for invoking such equitable principles against the tax administration.

The Blue Tax Return System (青色申告制度 - Ao-iro Shinkoku Seido): A Primer

Understanding Japan's blue tax return system is crucial to appreciating the case:

- Purpose: The ao-iro shinkoku seido aims to promote sound bookkeeping practices among taxpayers.

- Benefits: In return for maintaining detailed and accurate accounting records in a prescribed manner, taxpayers who opt into this system are eligible for various tax advantages. These can include special deductions, the ability to deduct salaries paid to family employees, the establishment of certain reserves and allowances as necessary expenses, and the carry-forward or carry-back of net business losses.

- Approval Required: To utilize the blue return system, a taxpayer must first apply for and receive approval from the director of the relevant tax office. This approval grants a specific legal status or qualification to file using a blue return form.

- Personal Nature: The blue return approval is generally considered personal to the taxpayer who received it (一身専属的 - isshin senzoku-teki) and is not automatically transferable to another individual, for instance, upon business succession.

Facts of the Case: An Unapproved Blue Return Filer

The case revolved around Mr. X, a former employee of the Moji Tax Office, who later became involved in a liquor sales business.

- The business was originally operated by Mr. A, X's elder brother and father-in-law, who had valid approval for filing blue tax returns. From around 1954, X gradually took over the primary operational responsibilities.

- Up to the 1970 tax year, returns for the business were filed in Mr. A's name under his blue return approval.

- In March 1972, for the 1971 income tax year, X filed a tax return for the business in his own name, using a blue return form. However, X had not applied for or obtained his own blue return approval.

- The Yahata Tax Office Director (hereafter "Y" or "the tax office") accepted X's 1971 blue return filing, apparently without verifying whether X personally held blue return approval status.

- For the subsequent tax years from 1972 through 1975, Y continued to send X blue return forms. X used these forms to file his tax returns, which Y accepted, and X paid the declared tax amounts.

- Throughout this entire period (1971-1975), the business maintained its bookkeeping and record preservation practices to a standard compliant with blue return requirements, continuing the system previously used under A's approval.

- In March 1976, Y informed X that X had never actually applied for blue return approval in his own name. X promptly submitted an application and received approval for the 1976 tax year and onwards.

- Despite this, Y subsequently issued corrective tax assessments (更正処分 - kōsei shobun) for X's income for the 1973 and 1974 tax years. These assessments treated X's filings for those years as "white returns" (ordinary returns not eligible for blue return benefits), thereby disallowing the advantages associated with blue returns. Y also imposed an additional tax for underreporting (過少申告加算税 - kashō shinkoku kasanszei).

Lower Courts' Rulings: Focus on Substance and Good Faith

The case then proceeded through the lower courts:

- The Fukuoka District Court (first instance) ruled in favor of X, revoking the corrective assessments and the underreporting penalties. The court reasoned that the primary purpose of the blue return system is to encourage and ensure the maintenance of proper books and records. If this underlying purpose was fulfilled, the court believed there could be exceptional situations where a return could be recognized as a blue return even without formal approval. Given the gradual business succession, the consistent high standard of bookkeeping, and the fact that X was not attempting to gain an unjust tax advantage, the District Court found that denying blue return status merely because of the missing application, especially in light of the tax office's conduct, would violate the principle of good faith and trust (shingisoku).

- The Fukuoka High Court (second instance) upheld the District Court's decision regarding the violation of shingisoku. It reiterated that X's record-keeping was sound and stated that X was "not gaining an unfair tax advantage".

The tax office (Y) appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding Legal Formalities and Defining Shingisoku in Tax Law

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of October 30, 1987, overturned the rulings of the lower courts and remanded the case.

Blue Return Approval is Indispensable

- The Court emphasized that blue return approval is a "constitutive disposition" (sekken-teki shobun) – an administrative act that confers a special legal status or qualification upon the taxpayer. This status allows the taxpayer to file using the special blue return forms, which come with various procedural and substantive tax benefits.

- The Income Tax Act provides a clear mechanism for obtaining this approval, including specific grounds for rejection and provisions for "deemed approval" if the tax office doesn't act on an application within a set timeframe. This system is designed to ensure that eligible taxpayers can obtain approval without undue delay.

- Crucially, the Court stated that under this statutory framework, even if a taxpayer (like X) takes over a business from a predecessor (A) who had blue return approval, the successor must independently apply for and receive their own approval. Filing a return on a blue form without such personal approval does not grant it blue return status.

- Therefore, the lower courts' suggestion that there could be "exceptional cases" where blue return status is recognized without formal approval was an error in interpreting the Income Tax Act. X's returns for 1973 and 1974, filed without his own approval, could not be treated as blue returns.

The Principle of Good Faith and Trust (Shingisoku) in Tax Law

The Supreme Court then addressed the core issue: whether the principle of good faith and trust could prevent the tax office from making corrective assessments that were otherwise consistent with the tax statutes.

- General Applicability: The Court acknowledged that shingisoku, as a general principle of law, can theoretically be applied in tax law relationships to invalidate a tax assessment that technically conforms to tax statutes.

- Strict Conditions for Application: However, its application in tax law must be approached with extreme caution and restrictiveness. This is due to the fundamental "principle of administration by law" (法律による行政の原理 - hōritsu ni yoru gyōsei no genri), and particularly the paramount "principle of no taxation without law" (租税法律主義 - sozei hōritsu shugi) that governs tax relationships.

- The Court declared that shingisoku should only be considered to negate a lawful tax assessment in "exceptional circumstances" (特別の事情 - tokubetsu no jijō) where protecting the taxpayer's trust by waiving the tax is deemed necessary to prevent a profound injustice, even if it means sacrificing the broader goals of equality and fairness among taxpayers that tax statutes strive to achieve.

- Key Factors for "Exceptional Circumstances": The Supreme Court laid out a set of essential factors to be considered when determining if such exceptional circumstances exist. At a minimum, these include:

- Public Expression of View by Tax Authority: The tax authority must have made a clear "public expression of view" (kōteki kenkai no hyōji) upon which the taxpayer could reasonably rely.

- Taxpayer's Reliance and Action: The taxpayer must have genuinely trusted this public expression and acted in reliance upon it.

- Subsequent Contradictory Action: The tax authority must have later taken an action (such as the disputed tax assessment) that contradicted its earlier public expression.

- Resulting Economic Detriment: The taxpayer must have suffered an economic disadvantage as a direct result of this contradictory action.

- Absence of Taxpayer Fault: The taxpayer must not have been at fault or negligent in placing their trust in the tax authority's expression and in acting upon that trust.

Application to X's Circumstances

Applying these stringent criteria to the facts of X's case, the Supreme Court found that the conditions for invoking shingisoku were not met:

- No "Public Expression of View": The Court determined that the tax office's actions – merely accepting X's returns filed on blue forms and subsequently sending him new blue forms for the following years – did not constitute a "public expression of view" that X had valid blue return approval or that his filings would definitively be treated as such.

- The Court clarified that under Japan's self-assessment tax system, the act of filing a tax return is completed when the taxpayer submits the document to the tax office director. The director's acceptance of the return and the collection of the tax amount declared do not signify an official endorsement or approval of the return's contents. Tax authorities retain the right to examine and correct returns later (as per Article 24 of the General Law of National Taxes).

- Furthermore, a taxpayer filing a return on a blue form cannot be construed as an implicit application for blue return approval. The tax office's failure to check X's approval status and its subsequent mailing of blue forms were not actions that X could reasonably interpret as granting him blue return approval. The commentary notes that sending forms can be seen as a mere "administrative service".

- Since this first critical condition (a "public expression of view") was not satisfied, the Supreme Court concluded there was no basis to consider the application of the principle of good faith and trust to invalidate the corrective assessments.

Outcome

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its interpretation and application of the law concerning both the blue return system and the principle of good faith and trust. The judgment of the High Court was reversed in the part unfavorable to the tax office, and the case was remanded to the Fukuoka High Court for further proceedings. The instruction was to re-examine the legality of the corrective assessments on the premise that X's returns for 1973 and 1974 were to be treated as white returns.

Analysis and Implications

This 1987 Supreme Court decision has had a lasting impact on the understanding and application of the principle of good faith and trust in Japanese tax law:

- Primacy of Legal Formality in Tax Law: The judgment strongly emphasizes the importance of adhering to formal legal requirements in tax matters. For systems like the blue return scheme, which offer significant benefits, obtaining the requisite formal approval is indispensable. Good intentions or substantive compliance (like X's good bookkeeping) cannot, by themselves, substitute for mandated legal formalities.

- Extremely High Bar for Shingisoku in Tax Disputes: The ruling established a very demanding threshold for taxpayers seeking to invoke shingisoku against a tax assessment. It clarified that mere perceived acquiescence, administrative oversight, or routine actions by tax authorities are generally insufficient grounds for such a claim. The "exceptional circumstances" test, requiring a potential injustice that outweighs fundamental tax principles, is difficult to meet.

- Narrow Interpretation of "Public Expression of View": The Court's interpretation of what constitutes a "public expression of view" by tax authorities is notably narrow. Routine administrative acts, such as accepting tax forms or mailing documents, do not qualify. This suggests that a more explicit, definitive, and official statement or guidance from the tax authority would be necessary to form a basis for legitimate taxpayer reliance.

- Balancing Taxpayer Protection with Legal Certainty and Equality: While the decision clearly prioritizes the principles of "no taxation without law," legal certainty, and the equal application of tax laws to all taxpayers, it does not entirely close the door on shingisoku. However, the window for its application is deliberately kept very narrow, reserved for situations of clear and egregious injustice stemming from misleading official representations.

- Important Lesson for Taxpayers: This case serves as a critical reminder for taxpayers in Japan to diligently ensure they have all necessary formal approvals and permissions before claiming any tax benefits or special statuses. They should be extremely cautious about interpreting routine administrative actions or informal communications from tax authorities as substantive endorsements or as a waiver of formal requirements.

- Outcome on Remand: The legal commentary accompanying the case summary notes that upon remand, the Fukuoka High Court ultimately dismissed X's claim. The reasons cited were consistent with the Supreme Court's strict criteria: there was no "public expression of view" by the tax office that X could rely on; being required to pay the legally correct amount of tax as a white return filer (without blue return benefits) did not constitute an undue economic detriment; and X, given his background as a former tax official, was deemed to have been at fault for not knowing that personal approval for blue returns was necessary.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1987 judgment in this "blue return" case significantly shaped the landscape of taxpayer rights and tax administration in Japan. It affirmed the critical importance of formal blue return approval and established that while the principle of good faith and trust (shingisoku) can, in theory, apply in tax law, its successful invocation requires truly exceptional circumstances. These circumstances must include, at a minimum, a clear and reliable "public expression of view" by the tax authority, on which the taxpayer reasonably relied, without fault, to their subsequent economic detriment when the authority acted inconsistently. The decision underscores the judiciary's commitment to upholding legal certainty and taxpayer equality in the complex and often contentious field of tax administration, placing a heavy onus on taxpayers to ensure strict compliance with formal statutory requirements.