Tax Investigations vs. Constitutional Rights: A 1972 Japanese Supreme Court Landmark

Case Title: Income Tax Act Violation Case

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

Judgment Date: November 22, 1972

Case Number: 1969 (A) No. 734

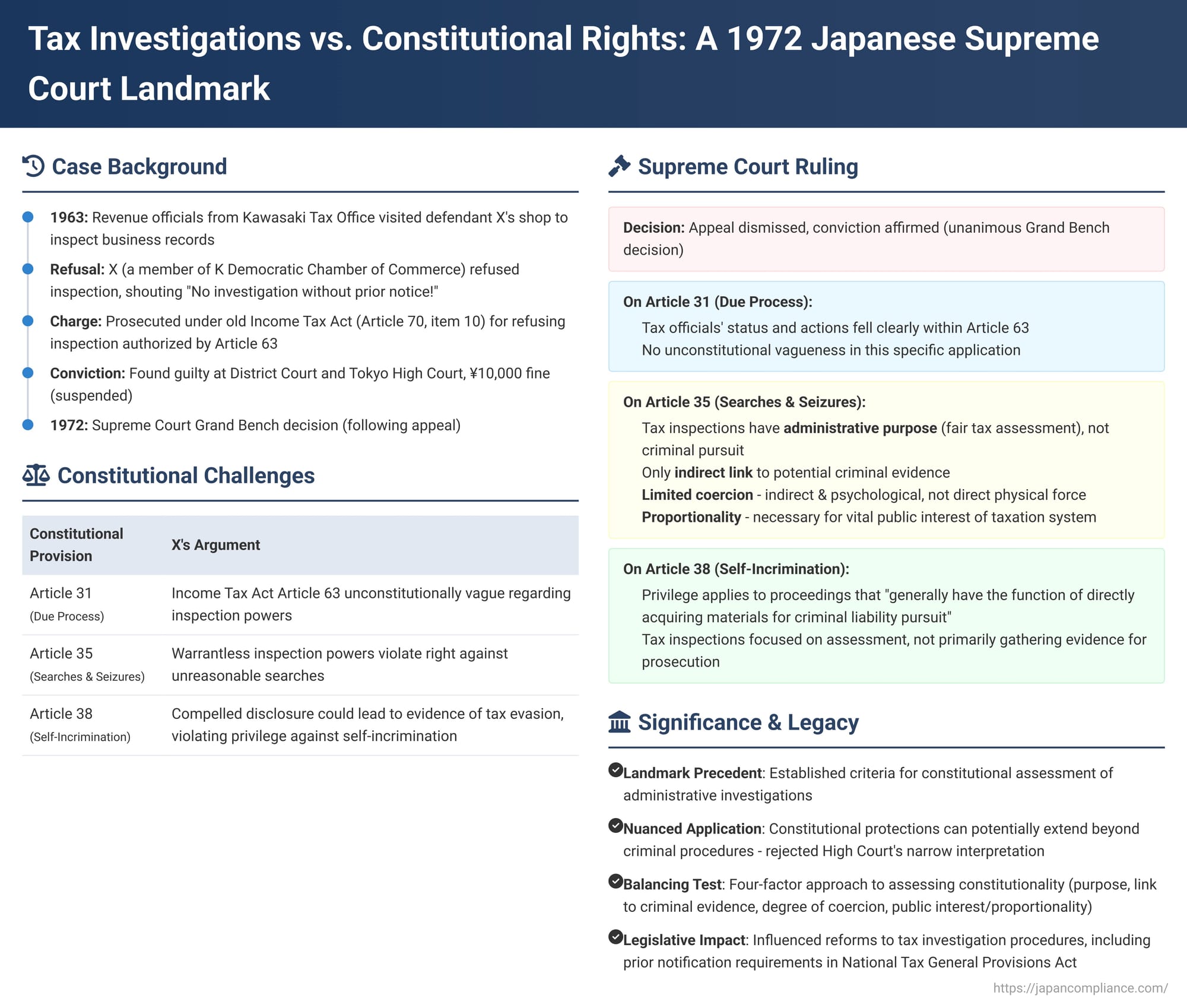

This seminal 1972 Grand Bench decision of the Supreme Court of Japan addressed fundamental constitutional questions arising from the exercise of tax investigation powers by revenue officials. The case involved a taxpayer, X, who was prosecuted for refusing to comply with an inspection of his business records. His appeal challenged the constitutionality of the then-existing Income Tax Act provisions authorizing such inspections, alleging violations of due process, the right against unreasonable searches and seizures, and the privilege against self-incrimination.

Background: A Taxpayer's Resistance

The defendant, X, operated a meat sales business with his wife. Around 1955, he joined the K Democratic Chamber of Commerce and Industry (K Minshō) in Kawasaki, later becoming an officer. At that time, there were ongoing conflicts between members of such "Minshō" organizations (primarily small and medium-sized business owners) and local tax offices concerning tax investigations. The K Minshō, like similar groups, aimed to promote what it termed the "democratization of tax administration," conduct tax system research, and provide tax and business management guidance and consultation to its members, including negotiating with tax authorities. Since its establishment, the K Minshō in Kawasaki was reportedly one of the most influential such groups within the jurisdiction of the Tokyo Regional Taxation Bureau, and some of its members were known to engage in group demonstrations and exert pressure on tax offices.

Against this backdrop, around May 1963, the National Tax Agency had identified Minshō organizations as a significant impediment to proper tax enforcement and investigation. Consequently, it had issued directives to tax offices to conduct thorough income investigations of Minshō members.

The Incident:

On October 3, 1963, revenue officials from the Kawasaki Tax Office visited X's combined residence and shop. Their purpose was to conduct an investigation related to X's final income tax return for the year 1962, specifically intending to inspect his business books and documents.

X resisted the inspection. He reportedly shouted, "No, no, I can't comply with an investigation without prior notice!" He also physically interfered by pulling one of the official's upper arms and saying, "Let's go over there." Due to this refusal, X was subsequently indicted and prosecuted for violating the old Income Tax Act.

Relevant Legal Provisions (Old Income Tax Act, prior to 1965 amendment):

- Article 63: Stipulated that revenue officials (shuzei kanri), when deemed necessary for an income tax investigation, could question taxpayers or other relevant persons, or inspect their business-related books, documents, or other items.

- Article 70, item 10: Prescribed penalties (imprisonment for up to one year or a fine of up to 200,000 yen) for any person who "refused, obstructed, or evaded an inspection" conducted under Article 63.

- Article 70, item 12: Similarly penalized those who "did not answer questions" during such an investigation.

Lower Court Proceedings:

Both the first instance court and the Tokyo High Court found X guilty of violating the Income Tax Act. He was sentenced to a fine of 10,000 yen, with the execution of the sentence suspended for two years.

X's Appeal to the Supreme Court:

X appealed to the Supreme Court, raising several constitutional arguments:

- Violation of Article 31 (Due Process - Procedural Guarantees): He contended that Article 63 of the old Income Tax Act, which defined the substance of the offense under Article 70, item 10, was unconstitutionally vague regarding the scope and meaning of the inspection powers, thereby violating the due process clause.

- Violation of Article 35 (Right against Unreasonable Searches and Seizures): He argued that Articles 70, item 10, and 63 were unconstitutional because they authorized compulsory inspection of documents without a warrant issued by a court, thereby infringing the right to be secure against entry, search, and seizure.

- Violation of Article 38 (Privilege Against Self-Incrimination): He asserted that the inspection and questioning powers under Articles 63 and 70, items 10 and 12, effectively compelled individuals to provide information that could potentially lead to criminal prosecution for tax evasion, thus violating the privilege against self-incrimination.

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench Judgment

The Supreme Court, sitting as a Grand Bench, unanimously dismissed X's appeal on November 22, 1972, upholding his conviction. The Court meticulously addressed each of X's constitutional claims.

1. Regarding the Alleged Violation of Article 31 (Due Process - Vagueness):

The Court found this argument to be without merit as applied to the facts of X's case. It noted that:

- The investigation was initiated because the Kawasaki Tax Office, after reviewing X's 1962 final income tax return, suspected underreporting of income.

- The officials conducting the inspection were employees of the tax office's income tax division, engaged in the assessment and collection of income tax. They requested X to present his sales ledgers, purchase ledgers, and similar documents.

- The Court determined that the officials' status and their actions clearly fell within the conditions prescribed by Article 63 of the old Income Tax Act.

- Therefore, as applied to X's case, Article 63, which formed the basis of the criminal charge under Article 70, item 10, presented no ambiguity in its content or application. The claim of unconstitutional vagueness was dismissed as lacking a proper premise.

2. Regarding the Alleged Violation of Article 35 (Right Against Unreasonable Searches and Seizures - Warrantless Inspection):

This was a central point of the appeal. The Court acknowledged that the penal sanction in Article 70, item 10, for refusing inspection indeed had a coercive effect, compelling individuals to submit to the inspection provided under Article 63. However, it ultimately found no constitutional violation, based on a multi-faceted analysis:

- Purpose of the Inspection: The Court emphasized that inspections under Article 63 were conducted solely for the purpose of collecting data necessary for the fair and accurate assessment and collection of income tax. By their inherent nature, these inspections were not procedures aimed at the pursuit of criminal liability.

- Indirect Connection to Criminal Liability: While the Court conceded that an inspection might uncover facts of underreporting, which could, in turn, lead to the discovery of tax evasion (a criminal offense), this possibility did not mean that the inspection itself generally functioned as a direct means of acquiring or collecting evidence for criminal prosecution. The scope of these tax inspections was limited to matters concerning income tax, targeted specific individuals or entities based on their relationship to tax assessment and collection procedures, and focused on business-related books and records. The scope was not determined by suspicion of criminal tax evasion.

- Nature and Degree of Coercion: The method of compulsion involved imposing a penal sanction (under Article 70) on those who refused inspection without a justifiable reason. This was characterized as an indirect and psychological means of compelling submission. While the penalty was not insignificant, the Court found that the degree of coercion exerted did not reach a level that would severely overwhelm an individual's free will to the extent that it could be equated with direct physical force.

- Public Interest and Proportionality: The Court underscored the critical public interest in ensuring the proper functioning of the tax collection system, which forms the basis of national finance, and in achieving fair and accurate income tax assessment and collection. An effective inspection system was deemed indispensable for these purposes. Given these objectives and the necessity of the system, the Court concluded that the level of indirect coercion involved was not disproportionate or unreasonable as a means of ensuring the system's effectiveness.

- Scope of Constitutional Protection under Article 35: The Court stated that Article 35(1) of the Constitution (guaranteeing security from warrantless entry, search, and seizure) is primarily intended to ensure that coercive measures taken in the context of criminal liability pursuit procedures are subject to prior judicial restraint (i.e., warrants). However, it also significantly added that it would not be appropriate to conclude that all coercive measures in non-criminal procedures are automatically outside the protective ambit of Article 35 merely because the procedure is not aimed at criminal prosecution.

- Conclusion on Article 35: Weighing all these factors, the Supreme Court concluded that the inspection powers under Articles 70, item 10, and 63 of the old Income Tax Act, even without a general requirement for a prior judicial warrant, did not violate the spirit (hōi) of Article 35 of the Constitution. X's claim of unconstitutionality on this ground was therefore rejected.

3. Regarding the Alleged Violation of Article 38 (Privilege Against Self-Incrimination):

X argued that the inspection and questioning powers could compel him to provide information that might incriminate him for tax evasion, thus violating his Article 38 rights. The Court disagreed:

- It reiterated that the inspections and questions under these provisions were solely for fair tax assessment and collection, not for criminal pursuit, and did not generally function to directly gather evidence for criminal cases. Such a system was deemed to have public necessity and rationality. This applied to both the inspection power and the questioning power.

- The Court affirmed its precedent (a 1957 Grand Bench decision) that the spirit of Article 38(1) of the Constitution—that no person shall be compelled to testify against himself when facing the risk of criminal liability—extends not only to purely criminal proceedings but also to other types of proceedings that, in substance, generally have the function of directly acquiring or collecting materials for the pursuit of criminal liability.

- However, given the nature of the inspection and questioning powers under the old Income Tax Act as previously analyzed (i.e., primarily administrative and not directly aimed at criminal evidence gathering), the Court concluded that these provisions themselves could not be said to compel "testimony against oneself" in the sense prohibited by Article 38(1). This constitutional claim was also found to be without reason.

Clarification on Lower Court's Constitutional Interpretation:

The Supreme Court noted that the High Court, in its judgment, had stated that Articles 35 and 38 of the Constitution, being provisions related to criminal procedure, do not directly apply to administrative procedures. The Supreme Court found this specific interpretation by the High Court to be erroneous. However, since the High Court's ultimate conclusion—that the Income Tax Act provisions in question were not unconstitutional under Articles 35 and 38—was deemed correct by the Supreme Court, this error in constitutional interpretation by the High Court did not affect the final judgment.

The Supreme Court also dismissed X's other constitutional arguments (violations of Articles 14, 19, 21, 12, and 28) as either being based on factual premises not supported by the lower courts' findings or, in the case of Article 28 (workers' rights), being inapplicable as X's refusal of inspection was not deemed an exercise of collective labor rights.

Analysis and Enduring Significance

This 1972 Grand Bench decision remains a landmark in Japanese constitutional and administrative law, particularly concerning the interface between administrative investigations (especially tax audits) and fundamental human rights.

Evolution from Earlier Jurisprudence:

The judgment marked a significant development from a somewhat ambiguous 1955 Grand Bench ruling that had dealt with investigative procedures under the National Tax Evasion Control Act. That earlier decision had not definitively clarified whether constitutional protections like Article 35 (against unreasonable searches) applied to administrative procedures, nor had it clearly categorized those specific tax investigation procedures as either criminal or administrative in nature. The 1972 ruling came at a time when legal thinking about procedural controls over administrative investigations was still evolving.

Key Criteria for Upholding Warrantless Tax Inspections:

The Supreme Court, in upholding the warrantless tax inspection powers, articulated four key grounds:

- Administrative Purpose: The primary aim of the investigation was administrative (fair tax assessment and collection), not the pursuit of criminal liability.

- Indirect Link to Criminal Evidence: The inspection did not generally function as a direct means of gathering evidence for criminal prosecution, even if it could incidentally uncover information leading to such.

- Limited Degree of Coercion: The compulsion was indirect and psychological, relying on the threat of a penalty for non-compliance, and was not deemed equivalent to direct physical force that would overwhelm free will.

- Overriding Public Interest and Proportionality: The inspection system was deemed essential for the vital public interest of maintaining the national tax system, and the level of coercion was considered a not disproportionate or unreasonable means to ensure its effectiveness.

Nuance on the Scope of Constitutional Protections:

A crucial aspect of this judgment is that the Supreme Court did not adopt the stance that constitutional criminal procedure safeguards like Articles 35 and 38 never apply to administrative procedures. While the High Court had leaned in that direction, the Supreme Court explicitly corrected this, acknowledging that Article 35's protection, for instance, could extend beyond purely criminal proceedings. This was a significant step.

However, the judgment did not provide a clear roadmap for which specific types of administrative procedures would fall under the protective umbrella of these constitutional provisions. Critics at the time, and since, have pointed out that if tax investigations carrying penalties for non-compliance (as in X's case) are deemed to fall outside the general warrant requirement of Article 35, then it becomes difficult to imagine many administrative inspection regimes that would require a warrant. Given that tax investigations can indeed uncover evidence leading to criminal charges for tax evasion, some argue that such situations are precisely where Article 35 protections (if understood as safeguarding privacy and preventing arbitrary administrative intrusion) should be most salient.

An alternative interpretation of the Court's reasoning on the warrant issue is that since tax authorities typically have other investigative tools at their disposal (e.g., inquiries with third parties, information analysis), and the system relies heavily on taxpayer cooperation, a warrant to forcibly overcome resistance to this specific type of on-site inspection might not be constitutionally mandated if the primary goal is administrative data collection and other avenues can achieve the same end without direct confrontation.

Regarding Article 38 (the privilege against self-incrimination), the Court established a standard: the privilege applies not only to purely criminal proceedings but also to any other procedure that "in substance, generally has the function of directly acquiring materials for criminal liability pursuit." While this standard appears broad, its application to the income tax inspection powers in this case was found not to trigger the privilege. This led some to believe that the practical scope for invoking Article 38 in most administrative investigations might be quite limited.

Legislative Impact and Ongoing Debate:

The 1972 judgment fueled considerable discussion and eventually contributed to legislative reforms concerning tax investigation procedures. The National Tax General Provisions Act was later amended to include a specific chapter (Chapter 7-2) on "Tax Investigations." These provisions codified aspects such as the questioning and inspection powers related to income tax (Article 74-2) and, notably, introduced a general requirement for prior notification of tax investigations (Article 74-9), along with specified exceptions where prior notice is not required (Article 74-10).

These legislative developments reflect an ongoing effort to balance the needs of effective tax administration with taxpayer rights. The 1972 Supreme Court decision remains a critical reference point in this balance, particularly in discussions about whether statutory controls alone are sufficient for regulating administrative investigations, or whether more direct constitutional oversight is necessary, especially when information obtained through administrative means might later be used in criminal proceedings.

Underlying Context of Taxpayer Resistance:

The broader context of the case, involving organized taxpayer groups like the K Minshō and their confrontations with tax authorities, also invites reflection. Phenomena such as "slippage" (where laws are not uniformly or perfectly enforced due to resource constraints or policy choices) and the potential for selective or targeted enforcement against particular groups can contribute to taxpayer resistance and perceptions of unfairness in the tax system. Evaluating the effectiveness and fairness of regulatory regimes often requires looking beyond the letter of the law to these practical realities of enforcement.

In conclusion, the 1972 Grand Bench ruling in X's case is a foundational judgment in Japanese law concerning the constitutional limits of administrative investigative powers. While it upheld the challenged tax inspection provisions without a general warrant requirement, it significantly advanced the principle that fundamental constitutional safeguards, traditionally associated with criminal procedure, could, at least in theory, extend their protective reach to administrative processes. The criteria laid out by the Court for assessing the constitutionality of such powers continue to shape legal discourse and practice, even as statutory frameworks for administrative investigations and taxpayer rights continue to evolve.