Tax Exemptions and Public Land Use: Japanese Supreme Court on 'Rented for a Fee' and Mayor's Liability

Date of Judgment: December 20, 1994

Case Name: Claim for Damages (平成5年(行ツ)第15号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

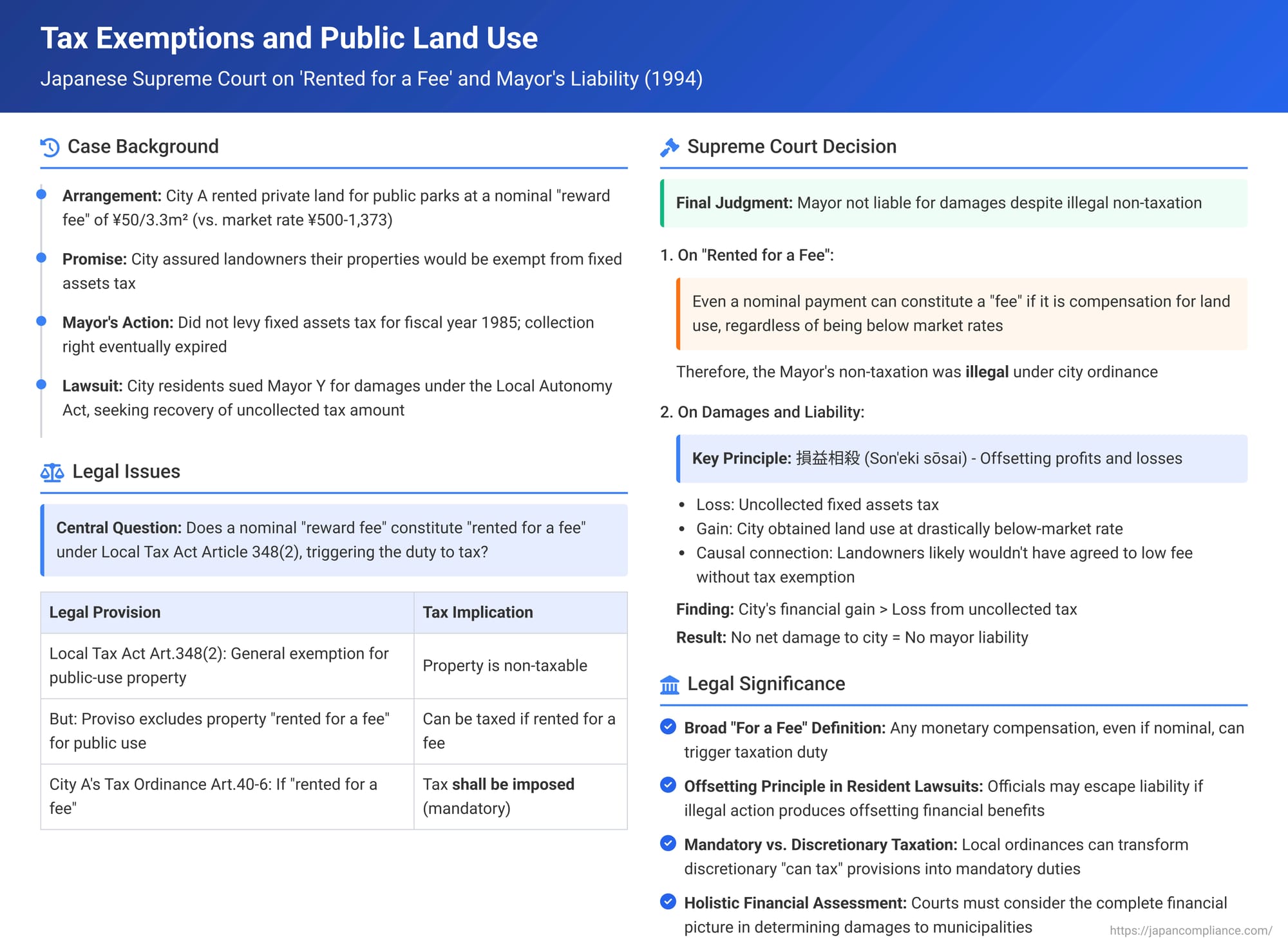

In a noteworthy decision on December 20, 1994, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a nuanced judgment concerning the fixed assets tax implications when a municipality rents private land for public use at a nominal fee. The case involved a residents' lawsuit against a city mayor, alleging financial damage to the city due to the mayor's failure to levy fixed assets tax on landowners. The Supreme Court clarified the meaning of "rented for a fee" under the Local Tax Act, finding that even a low "reward fee" qualified, thus making the non-taxation illegal. However, it ultimately absolved the mayor of liability by applying the principle of offsetting benefits, concluding that the city suffered no net financial damage.

City Parks on Private Land: The Tax Exemption Dilemma

The case originated in City A (identified in the judgment text as Higashimurayama City), which planned to establish public recreational facilities—tennis courts, a youth baseball field, and a gateball field—for its citizens. To secure the necessary land ("the subject lands"), City A approached private landowners. Instead of paying market-rate rent, the city proposed to pay a modest "reward fee" (hōshōhi) of ¥50 per 3.3 square meters per month. Concurrently, the city indicated to the landowners that if they provided their land under this arrangement, the fixed assets tax on these properties would be made non-taxable. The landowners agreed to this proposal, and City A proceeded to rent the subject lands.

It was noted that the typical market rent for similar land in the area, when leased for purposes other than building construction, ranged from ¥500 to ¥1,373 per 3.3 square meters per month. Furthermore, the estimated fixed assets tax that would have been levied on the subject lands amounted to ¥100 to ¥200 per 3.3 square meters per month. Thus, the ¥50 reward fee paid by the city was significantly below both the market rental value and even the potential tax liability on the properties.

The Mayor of City A, Y (the appellant, Kazuo Ichikawa), acting on the agreement with the landowners, implemented a measure not to levy fixed assets tax on the subject lands for the fiscal year 1985 (Showa 60) ("the subject non-taxation measure"). Subsequently, the city's right to collect this particular tax expired due to the statute of limitations.

A group of residents, X et al. (the respondents, Akiko Asaka et al.), filed a residents' lawsuit against Mayor Y. Such lawsuits are permissible under Article 242-2, paragraph 1, item 4 of the Local Autonomy Act (pre-2002 amendment version), allowing residents to sue local officials for actions deemed to cause financial damage to the municipality. The residents argued that Mayor Y had unlawfully neglected his duty to levy and collect fixed assets tax on the subject lands, thereby causing financial loss to City A, and they sought damages from Y equivalent to the uncollected tax amount.

The Legal Framework: Fixed Assets Tax Exemption and "Rented for a Fee"

The legal dispute centered on Article 348, paragraph 2 of the Local Tax Act. This provision generally grants an exemption from fixed assets tax for certain types of property used for public purposes, such as parks or public squares (referred to as "material non-taxation" as it focuses on the property's use or nature). However, a critical proviso to this paragraph states: "However, this shall not apply... to fixed assets which a person uses for any of the purposes... by renting them for a fee (yūryō de kariuketa) from their owner...". If property used for an exempt public purpose is "rented for a fee," the exemption can be lifted, and the municipality can impose fixed assets tax on the property owner.

Further complicating matters, City A's own municipal tax ordinance (Article 40-6, as referenced in the judgment text) stipulated that if fixed assets falling under the Local Tax Act's public use category were "rented for a fee," fixed assets tax "shall be imposed" (ka suru). This phrasing suggested a mandatory duty to tax in such circumstances, rather than mere discretion.

The core legal questions were:

- Did the significantly below-market "reward fee" paid by City A to the landowners constitute "renting for a fee" within the meaning of the Local Tax Act proviso?

- If so, was Mayor Y's decision not to levy fixed assets tax an illegal act?

- If the non-taxation was illegal, did it result in net financial damage to City A for which Mayor Y could be held personally liable, especially considering the low cost at which the city secured the use of the land?

The lower courts (Tokyo District Court and Tokyo High Court) had ruled in favor of the residents. They found that even if the reward fee was substantially lower than market rent, it still qualified as a "fee," making the rental "for a fee." Consequently, they held that Mayor Y's non-taxation measure was illegal under the city ordinance and that he was liable for damages equal to the uncollected tax. The High Court specifically rejected the argument that the city benefited from the low rental cost by stating that such a "factual benefit" was not a legal counterpart to the uncollected tax and therefore could not offset the damage. Mayor Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Two-Part Ruling

The Supreme Court overturned the judgments of the lower courts and dismissed the residents' claim for damages against Mayor Y. The Court's decision addressed two main points: the interpretation of "rented for a fee" and the calculation of damages.

Part 1: "Rented for a Fee" – A Broad Interpretation

The Supreme Court agreed with the lower courts on the interpretation of "rented for a fee" as used in the proviso to Article 348, paragraph 2 of the Local Tax Act and in City A's tax ordinance.

- The Court held that the phrase "rented for a fee" means that monetary payment is made as compensation for the use of the fixed asset, even if the amount of that payment does not reach the level of consideration typically found in ordinary market transactions for similar property.

- In this case, City A paid the landowners a "reward fee" that was consistently calculated at ¥50 per 3.3 square meters per month. The Court found that because this fee was calculated based on the area of land used and was paid in return for the city's use of the land, it constituted compensation for that use, regardless of its being substantially below market rates.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court affirmed that City A's arrangement with the landowners did indeed fall under the category of "renting for a fee". Consequently, Mayor Y was legally obligated under the city ordinance (which made taxation mandatory in such cases) to levy fixed assets tax on the landowners. His failure to do so meant that "the subject non-taxation measure was illegal".

Part 2: No Net Damage to the City Due to Offsetting Benefits (Application of Son'eki Sōsai)

This was the crucial point where the Supreme Court diverged from the lower courts and ultimately ruled in favor of Mayor Y.

- The Court stated that a residents' lawsuit seeking damages against a public official under Article 242-2, paragraph 1, item 4 of the Local Autonomy Act is, in terms of assessing damages, no different in nature from a general claim for damages under private law (e.g., the Civil Code).

- Therefore, when determining the existence and amount of damage, the legal principle of "offsetting profits and losses" (損益相殺 - son'eki sōsai) must be applied. This principle dictates that if an act causes damage but also results in a related benefit to the injured party, that benefit should be deducted from the loss to arrive at the net damage.

- Applying this to the current case:

- City A undoubtedly suffered a loss equivalent to the amount of fixed assets tax that went uncollected due to Mayor Y's illegal non-taxation measure.

- However, simultaneously, as a direct result of the agreement that included this (illegal) non-taxation assurance, City A secured the use of the subject lands by paying only a nominal "reward fee," thereby avoiding the much higher cost of market-rate rent. This avoidance of higher rental payments constituted a significant financial benefit or gain for the city.

- The Supreme Court found a clear "causal relationship" (相当因果関係 - sōtō inga kankei) and a "counterpart relationship" (対価関係 - taika kankei) between the illegal non-taxation measure and the benefit of securing land use at a very low cost. The Court reasoned that if Mayor Y had not implemented the non-taxation measure and had instead lawfully levied the fixed assets tax, it was highly probable that the landowners would not have agreed to lease their land for such a minimal reward fee. To secure the land under those circumstances, City A would likely have had to pay rent at or near prevailing market rates.

- The monetary value of this benefit (market rent avoided minus the nominal reward fee actually paid) was clearly greater than the amount of the loss (the uncollected fixed assets tax).

- Therefore, after applying the principle of offsetting profits and losses, the Supreme Court concluded that City A ultimately suffered no net financial damage as a result of Mayor Y's illegal non-taxation measure.

Because there was no net damage to the city, the residents' claim for damages against Mayor Y failed. The Supreme Court, therefore, quashed the High Court's decision and cancelled the first instance judgment, ultimately dismissing the residents' lawsuit.

Analysis and Implications

The Supreme Court's 1994 decision carries significant implications for local governance, tax administration, and resident lawsuits in Japan:

- Broad Interpretation of "Yūryō" (For a Fee): The ruling confirms that the term "for a fee" in the context of fixed assets tax exemptions is interpreted broadly. Any payment made as actual compensation for the use of property, regardless of whether it aligns with market rates, can trigger this condition. This means that even nominal or significantly below-market rental payments can lead to a property, otherwise exempt due to its public use, becoming taxable if the local ordinance so mandates. Municipalities must therefore be cautious when structuring agreements involving the use of private property for public purposes if their intent is to maintain the property's non-taxable status for the landowner.

- Discretion vs. Mandatory Taxation under Local Ordinances: The Local Tax Act's proviso to Article 348, paragraph 2 uses the phrase "can impose tax" (ka suru koto ga dekiru), which grants municipalities discretion in whether to tax properties rented "for a fee" for public use. However, as was the case with City A, if a local municipal ordinance makes such taxation mandatory ("shall be imposed" - ka suru), then local officials, including the mayor, lose that discretion and are bound to levy the tax. Mayor Y's failure to do so, despite the ordinance, rendered his action illegal.

- Application of Son'eki Sōsai (Offsetting Profits and Losses) in Resident Lawsuits: This is arguably the most impactful aspect of the judgment. The Supreme Court's clear application of the private law principle of son'eki sōsai to resident lawsuits under the Local Autonomy Act means that an official's action, even if proven to be technically illegal and causing a direct financial loss in one respect (such as uncollected taxes), might not result in personal liability for damages if that same illegal action simultaneously produced a causally linked offsetting financial benefit for the local government that equals or exceeds the loss. This provides a more holistic view of financial impact and can temper the potential financial liability of public officials.

- Policy Behind Public Use Exemptions and the "For a Fee" Proviso: Legal commentary explains that the general exemption for fixed assets used for public purposes (Local Tax Act Art. 348(2)) is intended to support the provision of public goods and services by reducing the tax burden on such properties. The proviso concerning assets "rented for a fee" exists because if the owner of the property is already deriving income from it (even if it's used for a public purpose by a lessee), the policy rationale for granting tax relief to that owner is diminished.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision in this 1994 case offers a nuanced resolution to a complex interplay of tax law, administrative law, and principles of damages. While it affirmed a broad interpretation of "rented for a fee," meaning that even nominal payments for the use of land can make that land taxable if used publicly, it crucially applied the principle of offsetting benefits (son'eki sōsai) to the mayor's conduct. This led to the conclusion that, despite the illegality of the non-taxation measure, the city suffered no net financial damage because the benefit of obtaining land use at a very low cost (a benefit directly linked to the non-taxation promise) outweighed the loss from the uncollected taxes. This ruling underscores the importance of considering the complete financial picture and the interconnectedness of actions and their consequences when assessing liability in resident lawsuits against public officials.