Tax-Exempt Status on the Line: Japanese Supreme Court on Calculating 'Taxable Sales' for Consumption Tax

Date of Judgment: February 1, 2005

Case Name: Consumption Tax Determination Disposition, etc. Invalidation Lawsuit (平成12年(行ヒ)第126号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

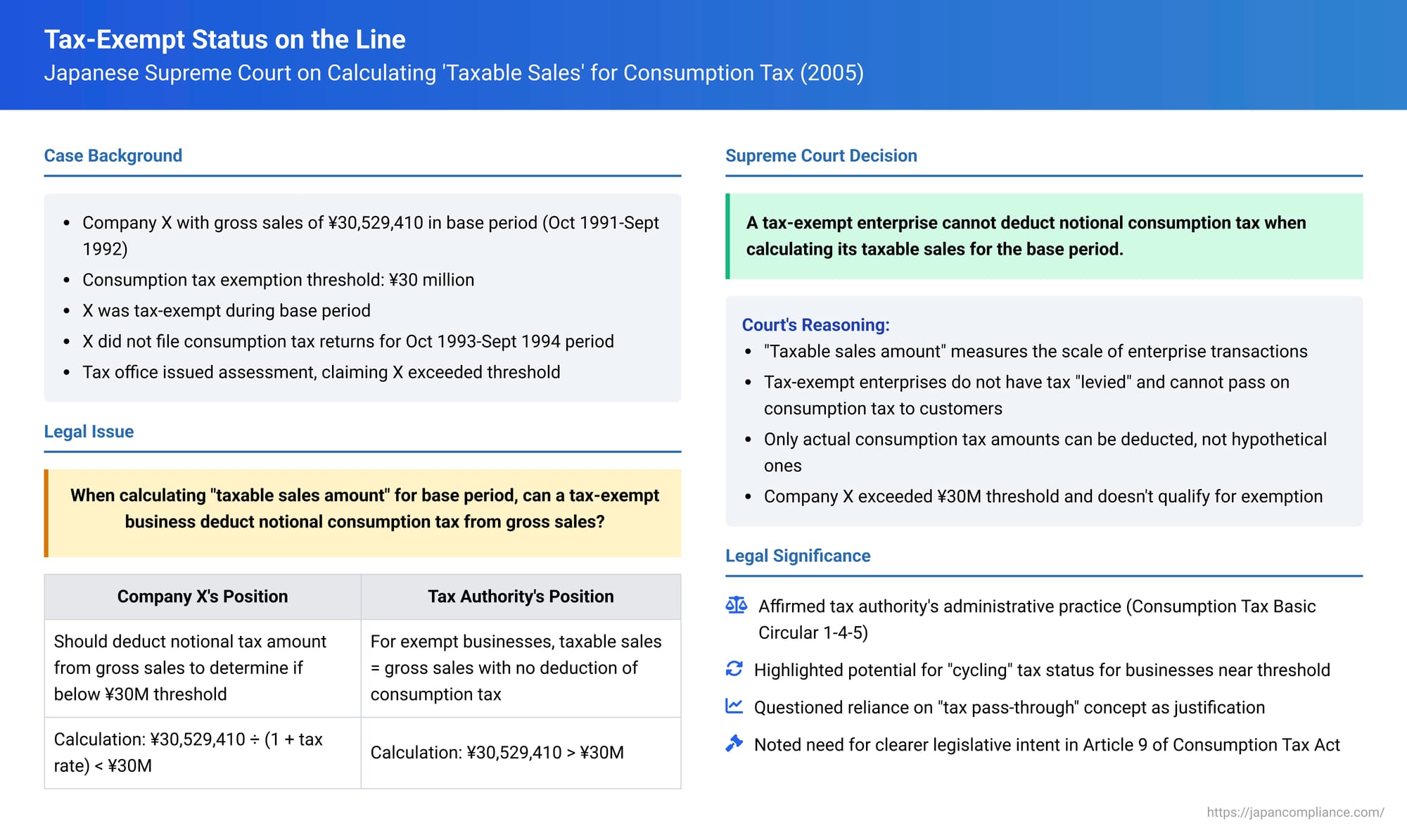

In a significant decision clarifying the application of Japan's consumption tax exemption for small-scale enterprises, the Supreme Court on February 1, 2005, addressed how an already tax-exempt business should calculate its "taxable sales amount" for a base period. This calculation is crucial as it determines whether the enterprise continues to qualify for tax exemption in a subsequent taxable period. The Court ruled that an enterprise exempt from consumption tax during the base period cannot deduct a notional amount of consumption tax from its gross sales when determining its taxable sales for that period.

The Consumption Tax Exemption and the Crucial Calculation

Japan's Consumption Tax Act provides an exemption from the obligation to pay consumption tax for small-scale enterprises. At the time of the transactions in this case, an enterprise whose "taxable sales amount" (課税売上高 - kazei uriage-daka) during its "base period" (基準期間 - kijun kikan – typically the business year two years prior) was ¥30 million or less was generally exempt from consumption tax for the current taxable period (Article 9, paragraph 1 of the Consumption Tax Act, "CTA").

The plaintiff, Company X, was an enterprise subject to the Consumption Tax Act. For its taxable period from October 1, 1993, to September 30, 1994 ("the subject taxable period"), X did not file a consumption tax return. X's reasoning was that it qualified as a tax-exempt enterprise. This assessment was based on its calculation of the taxable sales amount for the relevant base period, which was from October 1, 1991, to September 30, 1992 ("the subject base period").

During the subject base period, X was, in fact, a tax-exempt enterprise. Its actual gross sales for that period amounted to ¥30,529,410, a figure slightly above the ¥30 million exemption threshold. However, X took the view that, in calculating its "taxable sales amount" for this base period, it should be entitled to deduct an amount equivalent to the consumption tax that it would have been liable for if it had been a taxable enterprise during that base period. By making such a deduction, X's calculated taxable sales amount for the base period would fall below the ¥30 million threshold, thereby, in its view, maintaining its tax-exempt status for the subject taxable period.

The head of the competent tax office, Y, disagreed with X's interpretation. Y determined that X did not qualify as a tax-exempt enterprise for the subject taxable period because its taxable sales amount for the base period, when calculated without deducting any notional consumption tax, exceeded ¥30 million. Consequently, Y issued a tax assessment to X for the consumption tax due for the subject taxable period (amounting to ¥399,400 after an initial correction) and also imposed a non-filing penalty (amounting to ¥58,500 after an initial correction). X challenged these dispositions, and after losing in the lower courts (Tokyo District Court and Tokyo High Court), appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Definitions: "Taxable Sales Amount" and "Consumption Tax to be Levied"

The dispute hinged on the interpretation of key definitions within the Consumption Tax Act:

- "Taxable sales amount" for the base period (CTA Article 9, paragraph 2, item 1): This provision defines how to calculate the taxable sales amount for the base period. For a corporation with a one-year base period, it is the total amount of consideration (as defined in CTA Article 28, paragraph 1) for taxable asset transfers, etc., made in Japan during that base period, less certain sales returns and allowances.

- "Consideration" for the tax base (CTA Article 28, paragraph 1): This article defines the tax base for consumption tax. It states that the tax base for the transfer of taxable assets is the "amount of consideration for the transfer of taxable assets (meaning the total amount of money, or the fair market value of non-monetary consideration or other economic benefits, received or receivable as consideration, and excluding an amount equivalent to the consumption tax to be levied [課されるべき消費税に相当する額 - kasareru beki shōhizei ni sōtō suru gaku] on the transfer of taxable assets, etc.)".

The central interpretative challenge was the meaning of the phrase "consumption tax to be levied" when applied to an enterprise that was tax-exempt during the base period and therefore had no consumption tax actually levied upon it for its sales in that period.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: No Deduction of Notional Tax for Exempt Enterprises

The Supreme Court dismissed Company X's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions and the tax office's position. The Court held that an enterprise that was tax-exempt during the base period cannot deduct a notional amount of consumption tax when calculating its taxable sales amount for that base period to determine its exemption status for a subsequent period.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Purpose of "Base Period Taxable Sales Amount": The "taxable sales amount" mentioned in Article 9, paragraph 1 of the CTA serves as the criterion for determining whether an enterprise qualifies as a small-scale enterprise eligible for consumption tax exemption. It is fundamentally a measure intended to gauge the "scale of the enterprise's transactions."

- Link to Tax Base Definition: Article 9, paragraph 2, item 1 defines this "taxable sales amount" by directly referencing the definition of the "amount of consideration" in Article 28, paragraph 1, which establishes the tax base for consumption tax. The tax base, being the amount of consideration for taxable asset transfers, is conceptually akin to sales revenue and directly reflects the scale of an enterprise's transactions.

- Rationale for Excluding Consumption Tax in Article 28(1): The Court explained that the reason Article 28, paragraph 1 excludes an "amount equivalent to the consumption tax to be levied" from the consideration received by an enterprise is that such consideration received by a taxable enterprise is generally understood to include an amount of consumption tax that the enterprise has passed on to its customers. It is therefore appropriate to exclude this passed-on tax component when determining the true economic base upon which the consumption tax itself should be levied.

- Application to Tax-Exempt Enterprises: A tax-exempt enterprise, by definition, does not have a legal obligation to pay consumption tax on its sales and, consequently, is not in a position to pass on to its customers any "consumption tax to be levied on itself." The Court reasoned that because tax-exempt enterprises do not bear this tax liability, the rationale for deducting an equivalent amount of consumption tax from their sales (as is done for taxable enterprises under Article 28(1)) does not apply to them. Such a deduction for a tax-exempt entity, the Court stated, is "not envisaged by the Act" (法の予定しないところ - hō no yotei shinai tokoro).

- Meaning of "Consumption Tax to be Levied": Based on the above, the Supreme Court concluded that when calculating the "base period taxable sales amount" under Article 9, paragraph 2, the phrase "amount equivalent to the consumption tax to be levied" (which is excluded from the consideration amount) refers to the consumption tax amount that is actually to be levied on the enterprise for the taxable period that constitutes the base period. It does not include a hypothetical or notional amount of consumption tax that a tax-exempt enterprise would have been liable for if it had been a taxable enterprise during that base period.

Applying this interpretation to Company X, since its gross sales in the subject base period (¥30,529,410) exceeded the ¥30 million threshold, and since X was tax-exempt during that base period (meaning no consumption tax was actually levied on its sales from which a deduction could be made), its "taxable sales amount" for that base period was its gross sales amount. This amount was above ¥30 million. Therefore, Company X did not qualify for tax exemption in the subsequent subject taxable period, and the tax office's assessment was deemed lawful.

Analysis and Implications

The Supreme Court's decision in this case had several notable implications:

- Affirmation of Tax Authority Practice: The ruling upheld the existing administrative practice of the tax authorities, which had been formalized in a Consumption Tax Basic Circular (1-4-5) issued in 1995, stating that tax-exempt enterprises should not deduct a consumption tax equivalent when calculating their base period taxable sales.

- Critique of the "Pass-Through" Rationale: Legal commentary on the decision has questioned the Supreme Court's reliance on the concept of tax "pass-through" (転嫁 - tenka) as a primary justification. Critics argue that the ability of an enterprise to pass on consumption tax to its customers is an economic phenomenon dependent on market conditions, supply and demand elasticity, and bargaining power, rather than a guaranteed legal right or obligation. The Court's assertion that tax-exempt businesses are not in a "position" to pass on tax has been viewed by some as normatively insufficient, given the economic nature of price setting.

- Potential for "Cycling" Tax Status: A practical consequence highlighted by commentators is the potential for businesses whose gross sales hover just above the exemption threshold to experience a "cycling" of their tax status. For example, if an exempt business's gross sales are slightly above ¥30 million, it becomes taxable. In the subsequent base period (when it is taxable), its "taxable sales" (calculated net of the actual consumption tax it now charges) might then fall below the ¥30 million threshold, potentially making it tax-exempt again two years later. If its gross sales remain stable, it could then exceed the threshold again when measured as an exempt entity, leading to an alternating taxable/exempt status. This outcome was seen by some as an arguably unintended consequence of the interpretation.

- Statutory Interpretation vs. Legislative Clarity: Some commentators have suggested that if the legislature had intended a different method for calculating base period taxable sales for enterprises that were already tax-exempt versus those that were already taxable, this distinction should ideally have been more explicitly stated within Article 9 of the CTA itself, rather than relying on an interpretation of Article 28, which is primarily concerned with defining the tax base for taxable enterprises. The argument is that Article 9 aims to provide a simple and uniform yardstick for measuring business scale for all enterprises to determine exemption eligibility.

Subsequent Legislative Changes to Exemption Thresholds

It is important to note that since this 2005 judgment, the landscape of consumption tax exemptions in Japan has evolved. The monetary threshold for the small-scale enterprise exemption was subsequently lowered from ¥30 million to ¥10 million (effective from April 1, 2004). Additionally, further rules, such as the "specified period" (特定期間 - tokutei kikan) test (introduced by the 2011 reforms, CTA Article 9-2), have been implemented, which can make an enterprise taxable even if its base period taxable sales are below the threshold, if its taxable sales (or salary payments) in a shorter, more recent period (the first six months of the preceding business year) exceed ¥10 million. However, the core principle established by this Supreme Court ruling concerning the method of calculating the base period taxable sales amount for an enterprise that was tax-exempt during that base period likely remains influential for interpreting that specific calculation.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision in this case provided a significant clarification regarding the calculation of the "taxable sales amount" for determining consumption tax exemption eligibility for small-scale enterprises in Japan. It firmly established that enterprises that were tax-exempt during their base period must use their gross sales figures from that period, without deducting any notional consumption tax amount, to determine if they remain below the exemption threshold for a subsequent period. While this ruling affirmed the prevailing tax administration practice, it also spurred further academic discussion regarding the economic underpinnings of the consumption tax system and the practical effects of its exemption rules on businesses operating near the threshold.