Tax Disputes: Can the Taxman Change Reasons in Court? A 1981 Blue Form Case

Judgment Date: July 14, 1981

Case Number: Showa 52 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 62 – Claim for Revocation of Corporation Tax Correction Disposition

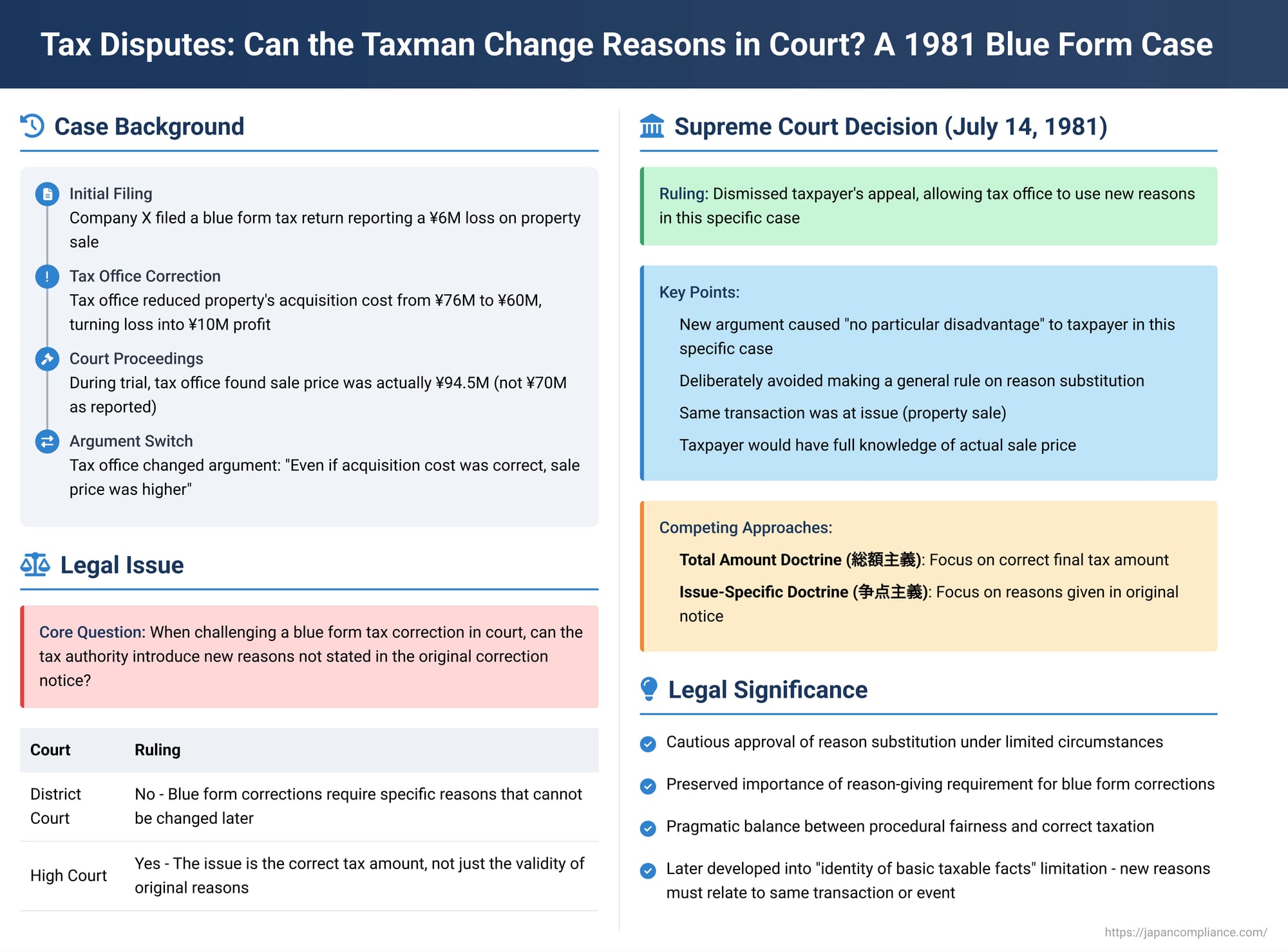

In Japan's tax system, taxpayers using the "blue form" (青色申告 - ao-iro shinkoku) method—which involves more rigorous bookkeeping in exchange for certain tax benefits—are entitled to be informed of the specific reasons if the tax authorities correct their filed returns. This reason-giving requirement is intended to ensure transparency and allow taxpayers to understand and, if necessary, contest the correction. But what happens if, during a court challenge to such a correction, the tax office seeks to justify its assessment using new reasons or facts not mentioned in the original notice? A 1981 Supreme Court decision addressed this delicate issue, balancing procedural fairness with the objective of accurate taxation.

The Case of the Disputed Property Sale

The plaintiff, K K.K. (hereinafter "X"), a family-owned real estate company, filed a blue form corporation tax return for the relevant business year. In this return, X reported a loss of just under 6 million yen from the sale of a property, declaring a sale price of 70 million yen and an acquisition cost of 76,009,600 yen.

The Nakagyo Tax Office Director (the Defendant, "Y") issued a correction disposition (更正処分 - kōsei shobun). One of the key reasons provided in the correction notice was that Y assessed the property's acquisition cost to be only 60 million yen. Based on this, Y determined that X had actually made a profit of 10 million yen on the sale, not a loss.

X filed a lawsuit to revoke this correction disposition. During the first instance trial at the Kyoto District Court, the facts began to evolve. It appeared that X's claimed acquisition cost of approximately 76 million yen (which included a 16,009,600 yen payment for business cessation compensation to facilitate the property acquisition) was likely correct. However, Y also uncovered new information suggesting that the actual sale price of the property was significantly higher than X had declared—94.5 million yen instead of 70 million yen.

Faced with this, Y introduced an "additional argument" (tsuika shuchō) in court: even if X's acquisition cost of 76 million yen was accepted, the newly discovered actual sale price of 94.5 million yen would mean X still realized a profit of nearly 18.5 million yen on the transaction. This profit would be even greater than the profit calculated in the original correction, thus, Y argued, the correction disposition was ultimately justified and should stand.

X countered that in a lawsuit challenging a correction made to a blue form return, the tax authority should not be permitted to introduce new factual grounds, different from those stated in the original notice's list of reasons, to uphold the disposition.

Lower Courts Clash: Strict Adherence vs. Overall Correctness

- The Kyoto District Court (first instance) sided with X. It held that the purpose of requiring reasons to be stated for blue form corrections meant that the tax authority could not later rely on different, unstated facts to justify its assessment. The court disallowed Y's additional argument and partially revoked the correction disposition concerning the disputed property transaction.

- The Osaka High Court (second instance) reversed this decision. While largely accepting the same factual findings, it permitted Y's additional argument. The High Court reasoned that a lawsuit to revoke a tax correction is essentially a lawsuit to confirm the non-existence of a tax debt. Therefore, the core factual issue is the correct total income for the business year, not merely the validity of the reasons initially provided by the tax office. If new income is identified based on reasons other than those originally stated, and the final income amount determined by the court equals or exceeds that in the correction disposition, then the disposition itself is not illegal. The High Court accordingly dismissed X's claim.

X appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that the High Court's ruling allowing the substitution of reasons was improper and contradicted precedents regarding the importance of reason-giving for blue form returns.

The Supreme Court's Cautious Approval (July 14, 1981)

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the Osaka High Court's decision in its conclusion. However, the Supreme Court's reasoning was notably more constrained than that of the High Court.

The Court acknowledged that Y had presented the argument about the higher sale price as a "new offensive/defensive method" concerning the lawfulness of the correction. It then stated that allowing Y to submit this additional argument, in this specific case, "does not cause any particular disadvantage" (kakubetsu no furieki o ataeru mono dewa nai) to X in its ability to contest the correction disposition.

Crucially, the Supreme Court explicitly stated that it was affirming the High Court's conclusion "without deciding generally whether any fact differing from the stated reasons can be argued" in a revocation suit concerning a blue form correction. Thus, while permitting the substitution in this instance, it deliberately avoided laying down a broad, universally applicable rule. The Court also found that this approach did not conflict with a precedent cited by X, which dealt with a different issue: whether a deficiency in the initial reasons provided could be "cured" by a subsequent administrative appeal decision.

The Underlying Debate: "Total Amount Doctrine" vs. "Issue-Specific Doctrine"

This case touches upon a long-standing debate in Japanese tax law regarding the fundamental nature, or "subject matter" (訴訟物 - soshōbutsu), of a lawsuit seeking to revoke a tax assessment:

- Total Amount Doctrine (総額主義 - sōgaku shugi): This view, generally favored in judicial practice, holds that the lawsuit is ultimately about the correctness of the final tax amount assessed. If the court finds that the correct total tax due is equal to or greater than the amount in the challenged disposition, the disposition will be upheld, even if the tax authority's original reasons were flawed or if new reasons are needed to support that total amount. This approach prioritizes substantive accuracy in taxation and allows more flexibility for the tax authority to correct its reasoning during litigation. The High Court's reasoning in this case strongly reflected this doctrine.

- Issue-Specific Doctrine / Point-at-Issue Doctrine (争点主義 - sōten shugi): This view, prominent among tax law scholars, argues that the lawsuit is about the correctness of the tax assessment based on the specific reasons and factual grounds provided by the tax authority at the time of the disposition. Proponents emphasize the importance of the taxpayer's procedural guarantees, including the right to know precisely why they are being assessed a certain way, so they can prepare an adequate defense. Under this view, allowing the tax authority to freely substitute reasons in court would undermine the purpose of the mandatory reason-giving for blue form returns.

While the Supreme Court in this 1981 decision did not explicitly endorse either doctrine, its pragmatic focus on whether the taxpayer X suffered "any particular disadvantage" allowed for an outcome consistent with the total amount doctrine in this instance. The Court seemed to treat the issue not as a strict matter of defining the lawsuit's subject matter, but as a question of whether limitations on the tax authority's arguments were warranted given the specific facts.

Why "No Particular Disadvantage" Was Key

The Supreme Court's emphasis on the absence of "particular disadvantage" to X was pivotal. Although not explicitly detailed in the judgment's reasoning for this point, the circumstances suggest why this might have been the case:

- The new reason introduced by Y (the higher actual sale price) pertained to the very same transaction—the sale of the specific property—that was already the central point of contention.

- As the seller, X would have been fully aware of all aspects of this transaction, including the actual sale price. The new argument did not introduce a completely unrelated taxable event that might have caught X off guard.

Legal commentary suggests that if the tax authority had attempted to introduce a completely different income item from an unrelated transaction, the court might well have found that this would cause a particular disadvantage and disallowed such a substitution.

The Significance of Reason-Giving for Blue Returns

The blue form tax return system is built on a premise of cooperation and trust, where taxpayers maintain detailed and reliable accounting records, and the tax authorities, in turn, are expected to respect these records and provide clear reasons if they deviate from the taxpayer's declaration. The Supreme Court's cautious phrasing in this judgment—avoiding a general endorsement of reason substitution—suggests it did not intend to diminish the importance of the reason-giving requirement for blue form corrections. Rather, it found a narrow ground to permit substitution when, on the specific facts, the taxpayer's ability to fairly contest the assessment was not compromised.

Post-Judgment Developments and Scholarly Views

Following this decision, legal scholarship and subsequent court cases have further explored the permissible scope of reason substitution in tax litigation. A prevailing view is that such substitution should generally be limited by the "identity of the basic taxable facts" (基本的(な)課税要件事実の同一性 - kihon-teki(na) kazei yōken jijitsu no dōitsusei). This means that if the new reason offered by the tax authority relates to the same fundamental economic transaction or taxable event that was initially in dispute, and if allowing the substitution does not unduly prejudice the taxpayer's procedural rights (e.g., their ability to prepare and present their case), then it may be permissible. However, introducing a completely different taxable event, even if it falls within the same tax year, might be disallowed.

Other considerations that scholars argue should limit reason substitution include the statutory exclusion period for making tax corrections (除斥期間 - joseki kikan), suggesting that reasons should not be substitutable after this period has expired. Additionally, some argue that if the tax authority wishes to add or change reasons, it should do so through a formal re-correction disposition (再更正 - sai-kōsei), as provided for in tax laws, rather than informally in court.

The quality of the initial reason-giving also remains crucial. If the tax authority provides only perfunctory or vague reasons initially, intending to freely substitute them later in court, this would undermine the entire purpose of the reason-giving requirement (which includes enabling the taxpayer to understand the basis of the disposition and to prepare for any challenge). Such a flawed initial reason-giving might be treated as a defect in the disposition itself.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1981 ruling in this blue form correction case navigated a complex area of tax procedure. It pragmatically allowed the tax authority to introduce a new factual basis to support its assessment during litigation, but did so on narrow grounds, emphasizing the absence of any specific prejudice to the taxpayer in that particular instance. The decision underscored the continuing tension in tax disputes between the state's objective of ensuring the correct amount of tax is ultimately paid and the vital need to protect taxpayers' procedural rights through transparent and adequate reason-giving by the tax authorities. While not providing a blanket approval for reason substitution, the judgment suggested that its limits are often defined by considerations of fairness and the taxpayer's unimpeded ability to mount a defense.