Tax Audits and Criminal Probes: Japanese Supreme Court on Use of Administratively Gathered Evidence

Date of Decision: January 20, 2004

Case Name: Corporate Tax Act Violation Case (平成15年(あ)第884号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

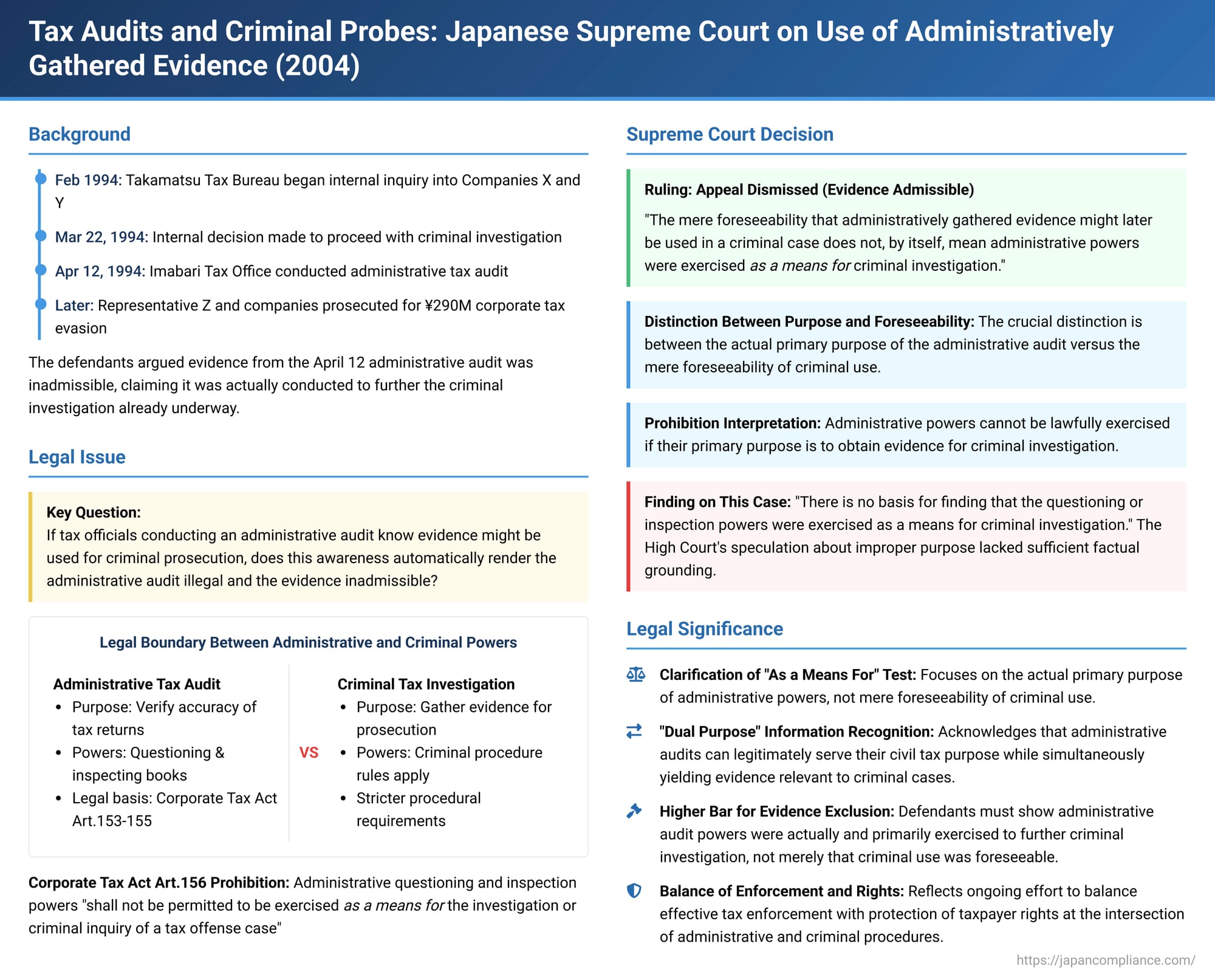

In a key decision on January 20, 2004, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the sensitive issue of using evidence obtained through administrative tax audits in subsequent criminal tax evasion prosecutions. The Court clarified that while administrative "questioning and inspection powers" (質問検査権 - shitsumon kensa ken) cannot be exercised as a means for criminal investigation, the mere foreseeability that information gathered during a legitimate administrative audit might later be used in a criminal case does not automatically render the administrative investigation illegal or the evidence inadmissible.

The Evasion and the Audit Trail

The case involved Z, who was the representative director or de facto manager of two companies, Company X and Company Y. Z, in conspiracy with the companies' chief accountant, was accused of corporate tax evasion over five fiscal years. The methods employed included omitting sales revenue from the books and reporting fictitious expenses, resulting in an alleged evasion of approximately ¥290 million in corporate taxes.

The timeline of the tax authorities' actions became a central point of contention:

- By February 1994, at the latest, the investigation and examination division (調査査察部 - chōsa sasatsubu) of the Takamatsu Regional Tax Bureau had already commenced an internal inquiry (naitei - 内偵) into the tax affairs of Companies X and Y. This internal inquiry is a preliminary stage that can lead to a formal criminal tax investigation.

- On March 22, 1994, an internal decision was made within the tax authorities to proceed with a formal criminal investigation (内偵立件決議 - naitei rikken ketsugi) targeting the companies and Z.

- Z, apparently becoming aware of this escalating scrutiny, consulted with a tax accountant, A, regarding the possibility of filing amended tax returns to correct past understatements.

- On April 11, 1994, tax accountant A met with the deputy head of the Imabari Tax Office (the local tax office with jurisdiction over the companies) to discuss the potential filing of amended returns.

- Crucially, on the following day, April 12, 1994, senior tax investigators from the Imabari Tax Office conducted on-site "tax audits" (税務調査 - zeimu chōsa) at the offices of Companies X and Y. These audits were carried out using the administrative questioning and inspection powers granted to tax officials under Articles 153 to 155 of the Corporate Tax Act (the versions prior to the 2001 amendment).

The defendants (Z, Company X, and Company Y) were subsequently prosecuted for corporate tax evasion. In their defense, they argued that the evidence obtained during the April 12 administrative tax audit by the Imabari Tax Office officials was inadmissible. Their core contention was that this administrative audit was, in reality, conducted as a means to further the already initiated criminal investigation, thus violating Article 156 of the Corporate Tax Act (which prohibited the use of administrative audit powers for criminal investigation purposes).

The first instance court (Matsuyama District Court) convicted Z and the companies. The Takamatsu High Court upheld these convictions. However, in its reasoning, the High Court acknowledged some ambiguity regarding the April 12 audit. It stated that it "could not rule out the possibility" that the tax officials' exercise of their administrative questioning and inspection powers on that day was, in part, carried out at the request of, or with the intent to cooperate with, those officials responsible for the criminal tax investigation, for the purpose of securing evidence. The High Court suggested that the April 12 audit "could be assessed as having been exercised, in one aspect, as a means for criminal investigation or prosecution." Despite this observation about a potential improper purpose, the High Court ultimately found the evidence admissible. The defendants appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, focusing on the alleged illegality of the April 12 audit and the inadmissibility of the evidence derived from it.

The Legal Boundary: Administrative Audit vs. Criminal Investigation Powers

The case brought to the fore the delicate legal boundary between administrative tax audits and criminal tax investigations in Japan.

- Administrative Tax Audits: These are conducted by tax officials under powers granted by specific tax laws (like the Corporate Tax Act or Income Tax Act, now largely consolidated into the General Act of National Taxes Articles 74-2 et seq.). Their primary purpose is to verify the accuracy of tax returns and determine the correct amount of civil tax liability. These audits involve questioning taxpayers and inspecting their books and records. While cooperation is expected, these are not typically coercive in the same way as criminal investigations.

- Criminal Tax Investigations (犯則事件の調査 - hansoku jiken no chōsa): When there is suspicion of deliberate tax evasion, tax authorities (often specialized units like the Regional Tax Bureau's investigation and examination division, or "Marusa" - マルサ) can conduct criminal investigations. These investigations are aimed at gathering evidence for potential criminal prosecution and are subject to stricter procedural rules, more akin to general criminal procedure, including in some instances the need for warrants for searches and seizures.

- The Prohibition in Corporate Tax Act Article 156: The version of Article 156 of the Corporate Tax Act applicable at the time (prior to its 2001 amendment; a similar provision is now found in Article 74-8 of the General Act of National Taxes) stipulated that the administrative powers of questioning and inspection granted under Articles 153 to 155 "shall not be permitted to be exercised as a means for the investigation or criminal inquiry of a tax offense case" (犯則事件の調査あるいは捜査のための手段として行使することは許されない - hansoku jiken no chōsa aruiwa sōsa no tame no shudan toshite kōshi suru koto wa yurusarenai). This provision aimed to prevent the misuse of administrative audit powers as a subterfuge to bypass the more stringent requirements of a formal criminal investigation.

The core legal question was: If tax officials conducting an administrative audit are aware that a criminal tax investigation is also being considered or is underway, and that any evidence they gather through administrative means might subsequently be used in a criminal prosecution, does this awareness or potential for "dual use" automatically mean that the administrative audit was conducted "as a means for" criminal investigation, thereby rendering it illegal and the evidence inadmissible?

The Supreme Court's Decision: Foreseeability of Criminal Use Doesn't Invalidate Administrative Audit

The Supreme Court dismissed the defendants' appeals and upheld their convictions. While it disagreed with a part of the High Court's reasoning, it ultimately affirmed the admissibility of the evidence obtained from the April 12 administrative tax audit.

The Supreme Court's key findings were:

- Interpretation of the Prohibition in Article 156: The Court first affirmed the fundamental principle: the administrative questioning and inspection powers granted to tax officials for determining civil tax liability cannot be lawfully exercised if their purpose is to obtain, collect, and preserve evidence for a criminal tax investigation or prosecution. These administrative powers are distinct from the powers and procedures applicable to criminal investigations.

- Distinction Between Purpose and Foreseeability of Criminal Use: This was the central point of the Supreme Court's decision. It held that: "However, even if it could be foreseen, during the exercise of the said questioning or inspection powers, that the evidentiary materials obtained and collected would later be used as evidence in a criminal tax case, this fact does not, by itself, immediately mean that the said questioning or inspection powers were exercised as a means for the investigation or criminal inquiry of a criminal tax case."

In essence, the mere foreseeability or anticipation that administratively gathered evidence might eventually be relevant to, and used in, a criminal proceeding does not retroactively taint the legality of the administrative investigation itself, provided that investigation was genuinely conducted for its proper administrative purpose. - No Evidence of Improper Primary Purpose in This Case: The Supreme Court reviewed the High Court's findings and the case record. It disagreed with the High Court's suggestion that the April 12 administrative audit could be assessed as having been partly motivated by a desire to assist the criminal investigation. The Supreme Court stated: "According to the original judgment's findings and the record, in the present case, it merely amounted to the fact that, during the exercise of the said questioning or inspection powers, it could be foreseen that the evidentiary materials obtained and collected would later be used as evidence in a criminal tax case. There is no basis for finding that the said questioning or inspection powers were exercised as a means for the investigation or criminal inquiry of a criminal tax case. Therefore, there was no illegality in the exercise of those powers."

The Supreme Court essentially found that the High Court had speculated about a possible improper purpose without sufficient factual grounding in the record. The actual evidence only supported the conclusion that criminal use was foreseeable, not that the administrative audit was a pretext or primarily driven by criminal investigative aims. - Admissibility of Evidence: Since the administrative tax audit conducted on April 12 was deemed lawful, the evidence obtained during that audit, and any evidence derived from subsequent procedures flowing from it, was admissible in the criminal trial.

Therefore, while disagreeing with the High Court's specific observation about the possibility of an improper motive for the April 12 audit, the Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's ultimate conclusion that the evidence was admissible and that the defendants' convictions should stand.

Analysis and Implications

This 2004 Supreme Court decision provides crucial guidance on the often-blurred lines between administrative tax audits and criminal tax investigations:

- Clarifying the "As a Means For" Test: The ruling is vital for its interpretation of the prohibition (formerly in CTA Art. 156, now in General Act Art. 74-8) against using administrative audit powers "as a means for" criminal investigation. The Supreme Court clarified that this prohibition targets the actual primary purpose for which the administrative powers are exercised. If the audit is genuinely aimed at determining civil tax liability, it is not rendered illegal merely because it might also uncover evidence of criminal wrongdoing or because criminal prosecution is a foreseeable outcome.

- Acknowledging the Reality of "Dual Purpose" Information Gathering: The decision implicitly recognizes that administrative tax audits can legitimately serve their primary civil tax determination purpose while simultaneously yielding information that may become relevant to a potential criminal tax case. As long as the administrative investigation is not a mere pretext or subterfuge for a criminal probe, the evidence it uncovers generally remains admissible. This is often referred to as the "dual purpose" or "parallel proceedings" issue in administrative and criminal law.

- Limits on Taxpayer Challenges to Evidence Admissibility: This ruling makes it more challenging for defendants in criminal tax evasion cases to seek the exclusion of evidence obtained during prior administrative audits simply by arguing that a criminal investigation was also being contemplated or was underway by the tax authorities at the time of the administrative audit. To succeed in such a challenge, the defense would likely need to present stronger evidence that the administrative audit powers were actually and primarily exercised for the purpose of furthering the criminal investigation, rather than for their legitimate administrative functions.

- Ongoing Efforts to Balance Enforcement and Rights: As noted in legal commentary, the Japanese legal system continues to evolve in balancing the needs of effective tax enforcement (which requires robust investigative powers) with the protection of taxpayer rights and due process guarantees, especially at the intersection of administrative and criminal procedures. The comprehensive amendments to the General Act of National Taxes in 2011 (effective from 2013), which introduced more detailed procedural rules for conducting tax audits, including requirements for prior notification and disclosure of reasons in many instances, reflect this ongoing effort to enhance transparency and fairness in tax administration.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2004 decision provides an important delineation of the boundary between administrative tax audits and criminal tax investigations in Japan. It establishes that evidence lawfully obtained through administrative questioning and inspection powers is not rendered inadmissible in a subsequent criminal tax prosecution merely because it was foreseeable at the time of the administrative audit that such evidence might eventually be used for criminal proceedings, or because there was some level of inter-agency awareness or coordination. The crucial factor is whether the administrative powers were actually exercised as a means for the criminal investigation, rather than for their legitimate administrative purpose of determining correct civil tax liability. This judgment affirms the tax authorities' ability to utilize information from proper administrative audits in subsequent criminal enforcement, provided the administrative audit itself was not a mere pretext for a criminal probe.