Talent Mobility in Japan’s Entertainment Industry: Antitrust Risks, “Oshigami” Lessons & Contract Tips

TL;DR

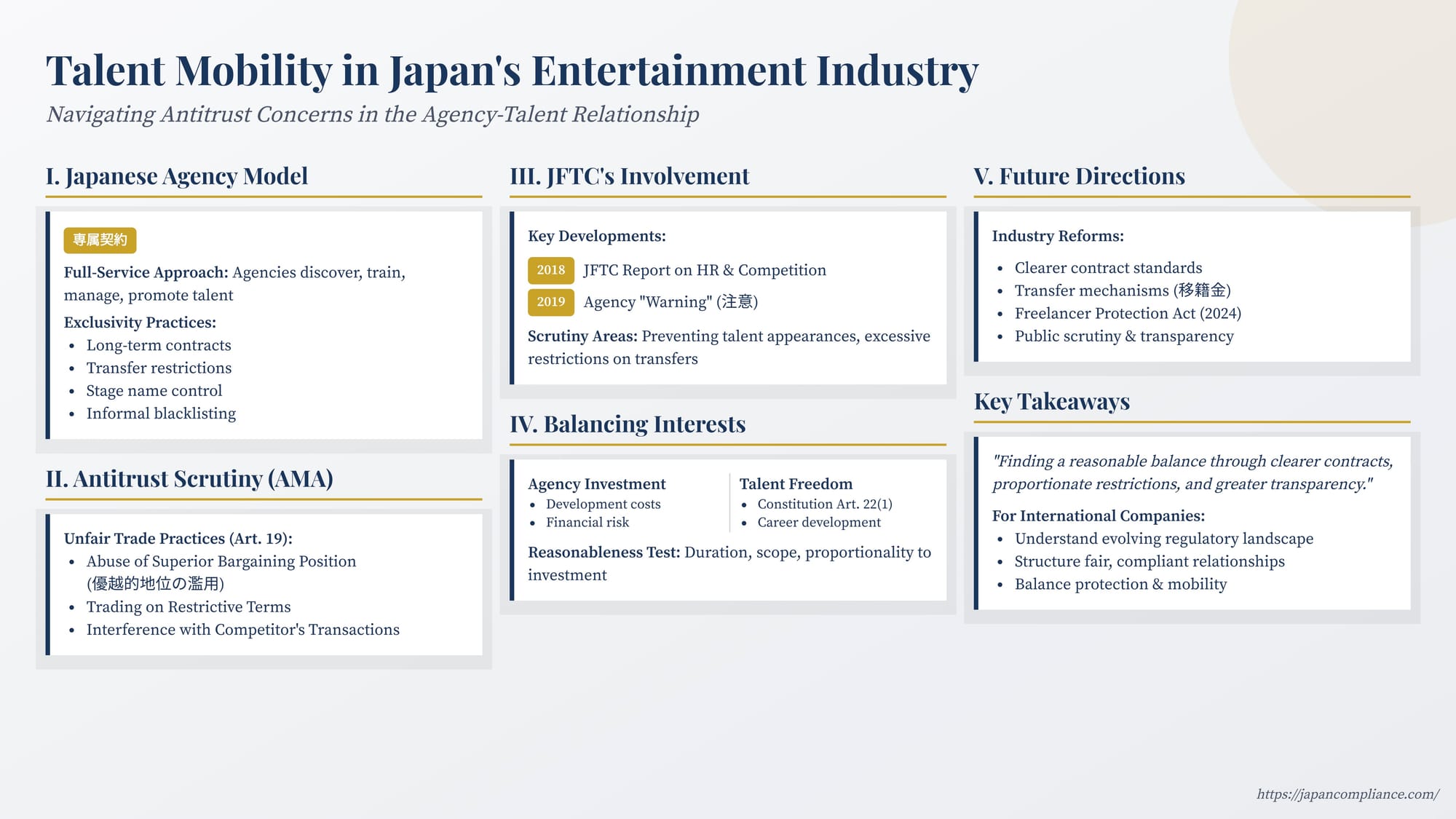

- Long-term exclusivity and post-contract non-competes in Japan’s talent-agency deals face growing Antimonopoly Act (AMA) scrutiny.

- JFTC investigations and the 2019 “idol-group” warning signalled that black-listing and excessive restrictions may breach Abuse-of-Superior-Bargaining-Position (ASBP) rules.

- Agencies must justify contract length, avoid retaliatory conduct and embrace clearer, proportionate terms before the 2024 Freelancer Protection Act tightens oversight.

Table of Contents

- The Japanese Agency Model and Exclusivity

- Antitrust Scrutiny under the AMA

- The JFTC's Involvement and Guidance

- Balancing Investment Protection and Talent Freedom

- Alternatives and Future Directions

- Conclusion

Japan's entertainment industry, encompassing actors, musicians, comedians (owarai geinin), models, and increasingly online personalities like VTubers, often operates under a structure significantly different from that in the United States. Long-term, exclusive contracts between talent (geinōjin) and management agencies (geinō jimusho) are common. While this system can facilitate talent development through agency investment, certain practices related to talent transfers (iseki) and independence (dokuritsu) have faced growing scrutiny under Japan's Antimonopoly Act (独占禁止法, AMA), raising important considerations for businesses operating in this space.

The Japanese Agency Model and Exclusivity

Unlike the typical US model where agents primarily focus on booking and talent assemble their own team, Japanese talent agencies often play a much broader role. They frequently discover, train, manage, promote, and book talent under comprehensive, exclusive management contracts (senzoku keiyaku). This "full-service" approach involves significant upfront investment by the agency in nurturing a performer's career, often before the performer generates substantial income.

This investment rationale is the primary justification agencies offer for demanding exclusivity during the contract term and, sometimes, imposing restrictions even after the contract ends. Common practices that raise competition law concerns include:

- Long-term Exclusivity: Contracts binding talent to a single agency for many years.

- Transfer/Independence Restrictions: Contract clauses or industry pressure preventing talent from moving to a competitor agency or working independently for a period after leaving.

- Control over Professional Identity: Attempts to control the use of a stage name (geimei) or likeness post-contract.

- Pressure Tactics: Alleged informal blacklisting or interference with a departed talent's opportunities.

Antitrust Scrutiny under the AMA

These practices can potentially violate Japan's AMA, primarily through the provisions governing Unfair Trade Practices (UTPs - Article 19, referencing the JFTC's General Designation). The relevant UTPs often discussed are:

- Abuse of Superior Bargaining Position (ASBP - General Designation Item 14, based on AMA Art. 2(9)(v)): This applies if an agency leverages its stronger bargaining position relative to the talent to impose unduly disadvantageous terms (e.g., excessively long exclusivity, unfair compensation, unreasonable post-contract restrictions).

- Trading on Restrictive Terms (General Designation Item 12): This prohibits imposing terms that unduly restrict a counterparty's business activities. Clauses preventing talent from working with any other party during or after the contract could fall under this if deemed unreasonable.

- Interference with a Competitor's Transactions (General Designation Item 14): This could apply if an agency actively obstructs a former talent's ability to sign with or receive work through a new agency or production company.

The JFTC's Involvement and Guidance

Historically, the AMA was rarely applied in the entertainment sector. However, this began to change around 2018-2019.

- 2018 JFTC Report: A key turning point was the JFTC's Competition Policy Research Center issuing a "Report by the Study Group on Human Resources and Competition Policy" in February 2018. This report acknowledged that freelancers, including entertainers and athletes, could be protected under the AMA, particularly from ASBP, paving the way for closer scrutiny.

- 2019 Agency "Warning": Public attention intensified in July 2019 when the JFTC reportedly issued a "warning" (chūi) to a major, influential talent agency. The warning related to suspicions that the agency had pressured television networks not to feature former members of a highly popular idol group after they left the agency. While a chūi is not a formal finding of violation (it typically means insufficient evidence for violation was found, but the conduct risks future violation), the JFTC's public acknowledgment of its investigation sent shockwaves through the industry.

- Subsequent Clarification: Following these events, the JFTC published guidance and Q&As clarifying that actions such as preventing talent from appearing with former colleagues without justification, or unduly restricting transfers or independence beyond what's reasonably needed to recoup investment, could potentially violate the AMA.

Despite this increased attention, challenges remain in applying the AMA. Proving ASBP, for instance, requires demonstrating not only the agency's superior position but also that the disadvantage caused was "unjust in light of normal business practices." Establishing these elements, especially regarding the impact on broader competition, can be difficult in individual talent disputes, particularly with smaller agencies.

Balancing Investment Protection and Talent Freedom

The core tension lies in balancing the agency's legitimate need to recoup its investment in talent development against the talent's freedom to pursue their career (a reflection of the constitutional freedom of occupation, Article 22(1)).

- Agency Investment: The argument that agencies undertake significant financial risk by investing heavily in often unproven talent is valid. Exclusivity for a reasonable period allows the agency a chance to earn back its investment through commissions on the talent's earnings. This investment benefits the talent and contributes new content and performers to the market, which can be seen as pro-competitive.

- Reasonableness of Restrictions: The key question under the AMA becomes whether the restrictions imposed (duration of exclusivity, post-contract non-competes) are reasonably necessary and proportionate to protect that investment interest.

- Duration: Excessively long exclusive contracts (e.g., potentially 7-10 years or more without clear justification or opt-out clauses) are likely to be viewed as potentially unreasonable.

- Non-Competes: Post-contract bans on working for any competitor are generally viewed skeptically under Japanese competition law. Agencies must demonstrate a specific, legitimate interest being protected (beyond just preventing competition). Protecting genuine trade secrets is a possible justification, but it's often argued that typical agency know-how or client lists don't qualify, and specific confidentiality clauses are a less restrictive means. Recouping training costs might justify some limited restriction, but it must be proportionate to the actual unrecouped investment.

- Transparency and Fairness: The JFTC emphasizes the importance of clear contracts and fair negotiations. Ambiguous contract terms, automatic renewals favoring the agency, excessive penalties for breach, or lack of transparency in accounting can be indicative of ASBP.

Alternatives and Future Directions

The industry and regulators are exploring ways to better balance these interests:

- Clearer Contract Standards: Industry associations, like the Japan Association of Music Enterprises (mentioned in the roundtable), are working on standard contract templates with clearer terms regarding duration, termination, and rights management, aiming to establish fairer norms.

- Transfer Mechanisms: While direct "transfer fees" (isekikin) common in sports face practical hurdles in entertainment (difficulty in valuation, varying agency sizes), mechanisms allowing talent to "buy out" remaining contract time or structured revenue-sharing agreements post-transfer might offer less restrictive alternatives to outright bans.

- Freelancer Protection Act: The "Act on the Promotion of Appropriate Transactions for Freelance Workers," expected to take effect in late 2024, aims to enhance protections for freelancers generally. It mandates written contracts specifying key terms (including remuneration and contract duration) and prohibits certain unfair conducts by commissioning businesses. While its direct application to the nuanced agency-talent relationship requires clarification, it signals a broader legislative push for fairer terms for non-employee workers.

- Public Scrutiny: High-profile disputes and scandals have increased public awareness and pressure on the industry to reform practices perceived as unfair or exploitative.

Conclusion

The relationship between talent and agencies in Japan's entertainment industry is under transformation, with increasing attention paid to fairness and mobility under the Antimonopoly Act. While agencies have legitimate interests in protecting their investments, practices that excessively restrict an entertainer's ability to change representation or work independently are facing heightened legal risk. The focus is shifting towards finding a reasonable balance through clearer contracts, proportionate restrictions, and greater transparency. For international companies engaging with Japanese talent or agencies, understanding this evolving regulatory landscape and the potential application of competition law is crucial for structuring fair and compliant relationships.

- Protecting Stardom in Japan: Publicity Rights for Stage & Group Names

- Digital Doubles in Japan: Legal Guide to AI Avatars, Privacy & Portrait Rights for Entertainers

- False IP Takedowns on Japanese E-Commerce Platforms: UCPA Liability & Risk-Control Guide

- JFTC Q&A on Talent Agency Practices and the AMA (Japanese)