Publicity & Portrait Rights in Japan: Legal Guide for US Marketing and Entertainment Businesses

TL;DR

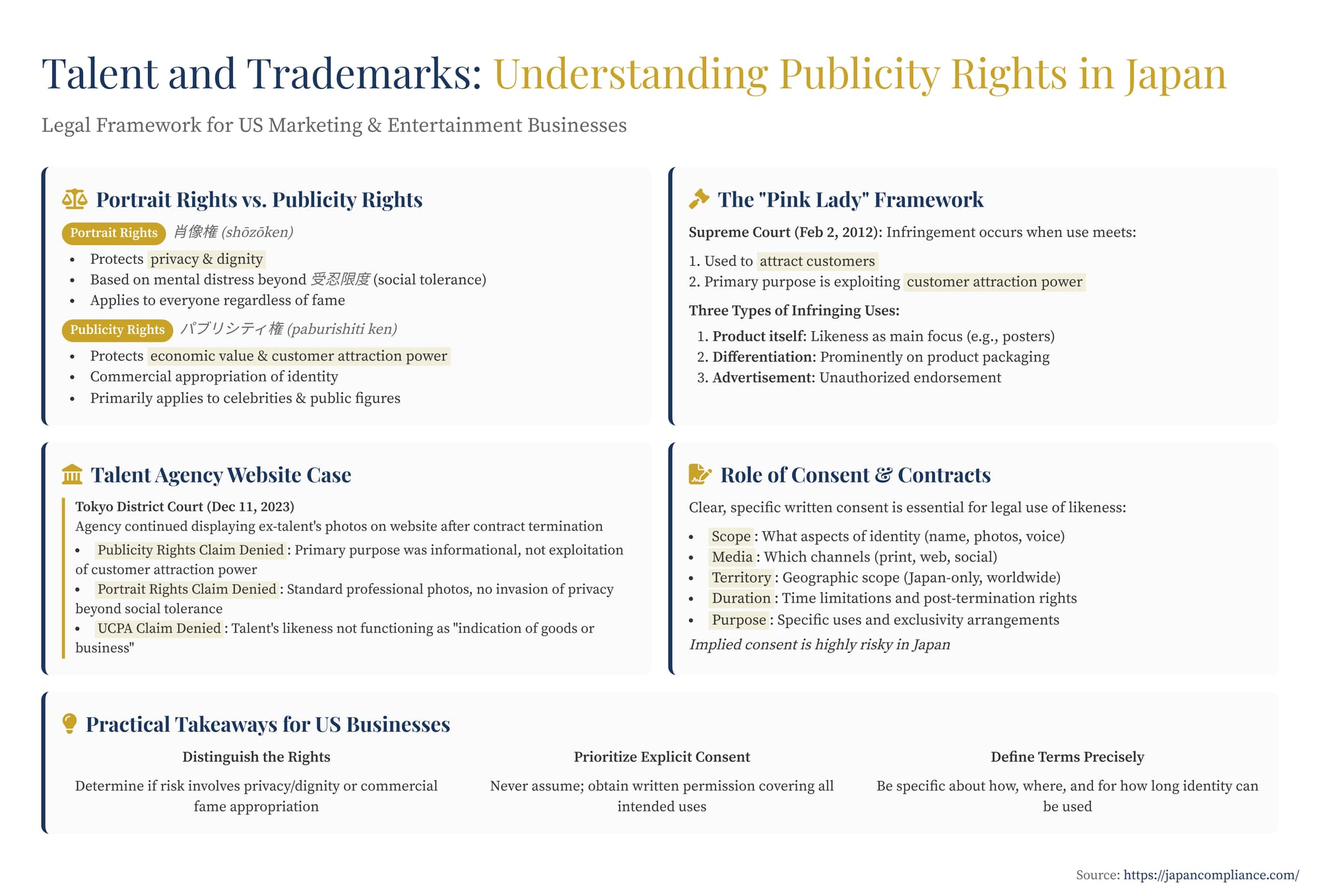

- Japan protects identity value through judge-made Publicity Rights (economic) and Portrait Rights (privacy/dignity).

- The Supreme Court’s Pink Lady test finds infringement only when use is exclusively to exploit customer-attraction power.

- A 2023 Tokyo case shows roster-style website uses can be lawful if primarily informational. Written consent and precise contracts remain best practice.

Table of Contents

- Publicity Rights vs. Portrait Rights: A Key Distinction

- The Core Test for Publicity Rights Infringement: The "Pink Lady" Framework

- The Talent Agency Website Case: Applying the Framework

- Can the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA) Protect Likenesses?

- The Crucial Role of Consent and Contracts

- Comparison with US Right of Publicity (Briefly)

- Practical Takeaways for US Businesses

- Conclusion

In today's image-driven world, the names and likenesses of individuals – particularly celebrities, athletes, and influencers – hold significant commercial value. For US businesses involved in marketing, advertising, entertainment, or merchandising in Japan, leveraging these personal identities can be highly effective. However, doing so requires careful navigation of Japan's unique legal framework surrounding personality rights, primarily the distinct concepts of "Publicity Rights" (パブリシティ権 - paburishiti ken) and "Portrait Rights" (肖像権 - shōzōken).

Unlike the US, where the Right of Publicity is often a distinct statutory or common law tort, Japan's approach is largely judge-made, evolving from broader constitutional and civil code protections for personality rights (人格権 - jinkakuken). Understanding the specific tests applied by Japanese courts, particularly regarding the commercial exploitation of fame versus the protection of personal privacy, is crucial. A recent Tokyo District Court decision concerning a talent agency's use of a former client's photographs provides a practical lens through which to examine these principles.

Publicity Rights vs. Portrait Rights: A Key Distinction

While both rights concern the use of a person's identity or appearance, their focus and scope differ significantly in Japanese law:

- Portrait Rights (肖像権 - shōzōken):

- Focus: Primarily protects an individual's privacy, dignity, and psychological well-being against the unauthorized taking (photographing, filming) and publication of their physical appearance.

- Harm: Measured by whether the unauthorized use causes mental distress exceeding the limits of social tolerance (junin gendo - 受忍限度). This involves a balancing test considering factors like the location (public vs. private), the nature and purpose of the depiction, and the extent of dissemination.

- Scope: Applies to everyone, regardless of fame. Even an ordinary person has the right not to have their photograph taken intrusively or published without consent in a way that causes unreasonable distress.

- Legal Basis: Rooted in the right to privacy and personality rights derived from the Constitution (Article 13) and general tort principles (Civil Code Article 709).

- Publicity Rights (パブリシティ権 - paburishiti ken):

- Focus: Protects the economic value associated with a person's identity – specifically, their power to attract customers or attention (customer attraction power - 顧客吸引力, kokyaku kyūinryoku) based on their name, likeness, or other identifying attributes.

- Harm: Measured primarily by the unauthorized commercial appropriation of this economic value.

- Scope: Primarily applies to famous individuals (celebrities, athletes, public figures) whose identities have acquired commercial value that can be licensed or exploited. While theoretically applicable to non-famous individuals if their likeness generates specific economic value in a context, it's most relevant for well-known personalities.

- Legal Basis: Also derived from personality rights, but specifically focusing on the economic aspect. The legal framework has been significantly shaped by landmark Supreme Court decisions.

Understanding this distinction is vital because the legal test for infringement differs substantially between the two.

The Core Test for Publicity Rights Infringement: The "Pink Lady" Framework

The leading authority on publicity rights infringement in Japan is the Supreme Court judgment in the "Pink Lady" case (Supreme Court, February 2, 2012). This decision established that an infringement of publicity rights occurs only when the use of a person's name, likeness, etc., meets two conditions:

- It is used as a means to attract customers (i.e., leveraging the person's fame or image for commercial gain).

- The primary purpose of the use is the exploitation of the customer attraction power inherent in the person's identity.

The court identified three main scenarios where such infringing use typically occurs:

- (Type 1) Use as the Product Itself: Using the person's likeness as the main focus of appreciation in products or services (e.g., selling unauthorized photographs, posters, or merchandise featuring the celebrity).

- (Type 2) Use for Differentiation: Using the person's likeness prominently on a product or its advertising to differentiate it from competitors, leveraging the celebrity's image to draw attention to the product itself.

- (Type 3) Use as an Advertisement: Using the person's name or likeness as an advertisement for a product or service, clearly identifying the person with the product or service to attract customers (e.g., unauthorized celebrity endorsements).

Crucially, the Pink Lady judgment implies that uses falling outside these categories, or where the exclusive purpose is not the exploitation of customer attraction power, generally do not constitute an infringement of publicity rights. This includes informational uses, news reporting, critical commentary, and potentially parody (though the boundaries here can be complex).

The Talent Agency Website Case: Applying the Framework

The Tokyo District Court decision of December 11, 2023, provides a useful illustration of how these principles are applied.

Background:

A talent (X) terminated their exclusive contract with their agency (Y). Despite the termination notice, the agency continued to feature the talent's photographs and profile on its official website for a period. The talent sued, claiming infringement of both publicity rights and portrait rights. (A separate claim under the Unfair Competition Prevention Act was also made).

Court's Decision on Publicity Rights:

The court denied the publicity rights claim. Its reasoning closely followed the Pink Lady framework:

- It found that the agency's purpose in displaying the photo and profile was primarily informational – specifically, to indicate the (past, during the relevant period) affiliation of the talent with the agency and to provide basic biographical details about the talent represented by the agency.

- This use did not fit into the three infringing categories identified in Pink Lady (it wasn't selling the photos themselves, using them to differentiate agency services generally, or using them as a specific advertisement beyond identifying the talent roster).

- Therefore, the court concluded that the use was not "exclusively for the purpose of utilizing the customer attraction power" of the talent's likeness. While the presence of famous talent on an agency roster inherently has some customer attraction power for the agency, the primary purpose of the specific profile display was deemed informational identification within that context.

Court's Decision on Portrait Rights:

The court also denied the portrait rights claim. It applied the "social tolerance" standard:

- The photographs themselves were standard professional headshots or profile pictures, not taken in a private or compromising context.

- Using them on the agency's website to identify a represented (or recently represented) talent was considered a use that did not invade the talent's privacy or cause mental distress beyond socially acceptable limits for a public-facing professional.

This case underscores that merely using a famous person's image, especially in a context related to their professional activities (like an agency roster), does not automatically infringe publicity or portrait rights if the primary purpose is informational and the use is not unduly intrusive or offensive.

Can the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA) Protect Likenesses?

The talent in the agency case also brought a secondary claim under Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA), specifically Article 2, Paragraph 1, Item 1, which prohibits the misappropriation of another party's "well-known indication of goods or business" (周知な商品等表示 - shūchi na shōhin tō hyōji) in a way that causes confusion.

The court swiftly dismissed this claim as well. The key reason was the failure to meet the requirement of an "indication of goods or business." The court found:

- The talent's name and likeness identified them as a famous performer or individual.

- It did not function as an indicator of the source of specific goods or services provided by the talent themselves (e.g., the talent's own production company or branded merchandise line). Their fame was personal, not inherently tied to a specific commercial enterprise operated by them.

- Therefore, their name/likeness did not qualify as a "well-known indication of goods or business" under the UCPA.

This highlights a general limitation: while the UCPA strongly protects trademarks and trade names, it is typically difficult to use it to protect a person's name or likeness as such, unless that identity has strongly acquired secondary meaning specifically as a source identifier for the individual's own distinct business activities, separate from their personal fame. Relying on publicity rights or portrait rights (via tort law) is usually the more appropriate avenue for protecting personal identity value.

The Crucial Role of Consent and Contracts

Given the nuances of Japanese case law, the most reliable way for businesses to legally use an individual's name or likeness is by obtaining clear, specific, and informed consent. This is typically achieved through well-drafted contracts.

For US businesses engaging talent, influencers, or even ordinary individuals for endorsements, advertising campaigns, or merchandising in Japan, contracts are paramount. Key considerations include:

- Scope of Consent: The agreement must clearly define what aspects of the person's identity can be used (name, specific photos, videos, voice, signature?), how they can be used (specific media channels – print, web, TV, social media?), where (geographic scope – Japan only, worldwide?), and for how long. Ambiguity often leads to disputes.

- Purpose Specification: Clearly state the intended purpose (e.g., "advertising campaign for Product X," "merchandise featuring Talent Y's likeness").

- Exclusivity: Define any exclusivity arrangements clearly.

- Compensation: Detail the payment structure.

- Termination and Post-Termination Rights: Specify what happens upon contract termination. Can the business continue using previously created materials? For how long? Under what conditions? The agency website case implicitly highlights the importance of this – had the contract clearly prohibited any post-termination use on the website, the outcome might have differed (though the infringement analysis itself might still stand, a breach of contract claim could arise).

- Model Releases: For non-celebrities appearing in advertisements or marketing materials, standard model releases securing consent are essential.

Relying on implied consent is highly risky in Japan. Written agreements tailored to the specific use case are the best practice.

Comparison with US Right of Publicity (Briefly)

While sharing the goal of protecting identity value, Japan's approach differs from the US Right of Publicity in key ways:

- Legal Basis: US rights vary significantly by state, often based on specific statutes or evolving common law torts focused on appropriation of commercial value. Japan's rights are judge-made interpretations of broader personality rights.

- Infringement Test: The US often focuses on whether the defendant appropriated the plaintiff's identity for commercial advantage without consent. While similar to Japan's Type 3 (advertising use), the strict "exclusive purpose of exploiting customer attraction" test from Pink Lady might be narrower than some US state approaches, potentially allowing more leeway for incidental or informational uses in Japan.

- Post-Mortem Rights: Many US states recognize publicity rights that survive death (descendible rights), allowing heirs to control the commercial use of a deceased celebrity's likeness. Post-mortem publicity rights are not clearly established in Japanese law, though related rights concerning reputation or privacy might persist to some extent.

Practical Takeaways for US Businesses

When planning to use names or likenesses in the Japanese market, US companies should:

- Distinguish the Rights: Determine if the primary legal risk involves privacy/dignity (Portrait Rights) or the appropriation of commercial fame (Publicity Rights), as the applicable tests differ.

- Prioritize Explicit Consent: Never assume consent. Obtain clear, specific, written permission covering the intended scope, duration, and purpose of use through carefully drafted contracts or release forms.

- Define Contractual Terms Precisely: Leave no room for ambiguity regarding how, where, and for how long a person's identity can be used, especially concerning post-termination usage.

- Evaluate Website/Informational Uses: Be cautious when using images even for seemingly informational purposes (e.g., showcasing clients, partners, or team members). Ensure the context doesn't inadvertently cross the line into primarily exploiting customer attraction power without clear consent for that purpose.

- Don't Rely Primarily on UCPA for Likeness: While relevant for trademarks, the UCPA is generally not the main tool for protecting personal likeness unless it functions unequivocally as a source identifier for that person's own business.

Conclusion

Japan provides legal protection for the personal and economic value inherent in an individual's identity, but through the distinct lenses of Portrait Rights and Publicity Rights. The landmark Pink Lady case established a specific, relatively narrow test for infringing Publicity Rights, focusing on uses exclusively aimed at exploiting customer attraction power. As the recent talent agency case illustrates, not all commercial uses of a celebrity's likeness meet this stringent test, particularly if the primary purpose can be framed as informational within a relevant context. For US businesses, the clearest path to avoiding legal pitfalls remains obtaining explicit, well-defined consent through carefully negotiated contracts that respect the nuances of Japanese personality rights law.

- False IP Takedowns on Japanese E-Commerce Platforms: UCPA Liability & Risk-Control Guide

- Who Owns AI-Generated Works in Japan? Copyright, Authorship & Article 2 Criteria Explained

- Antitrust Green Lights?: Navigating Sustainability Collaborations in Japan

- Agency for Cultural Affairs FAQ on Portrait & Publicity Rights (Japanese)