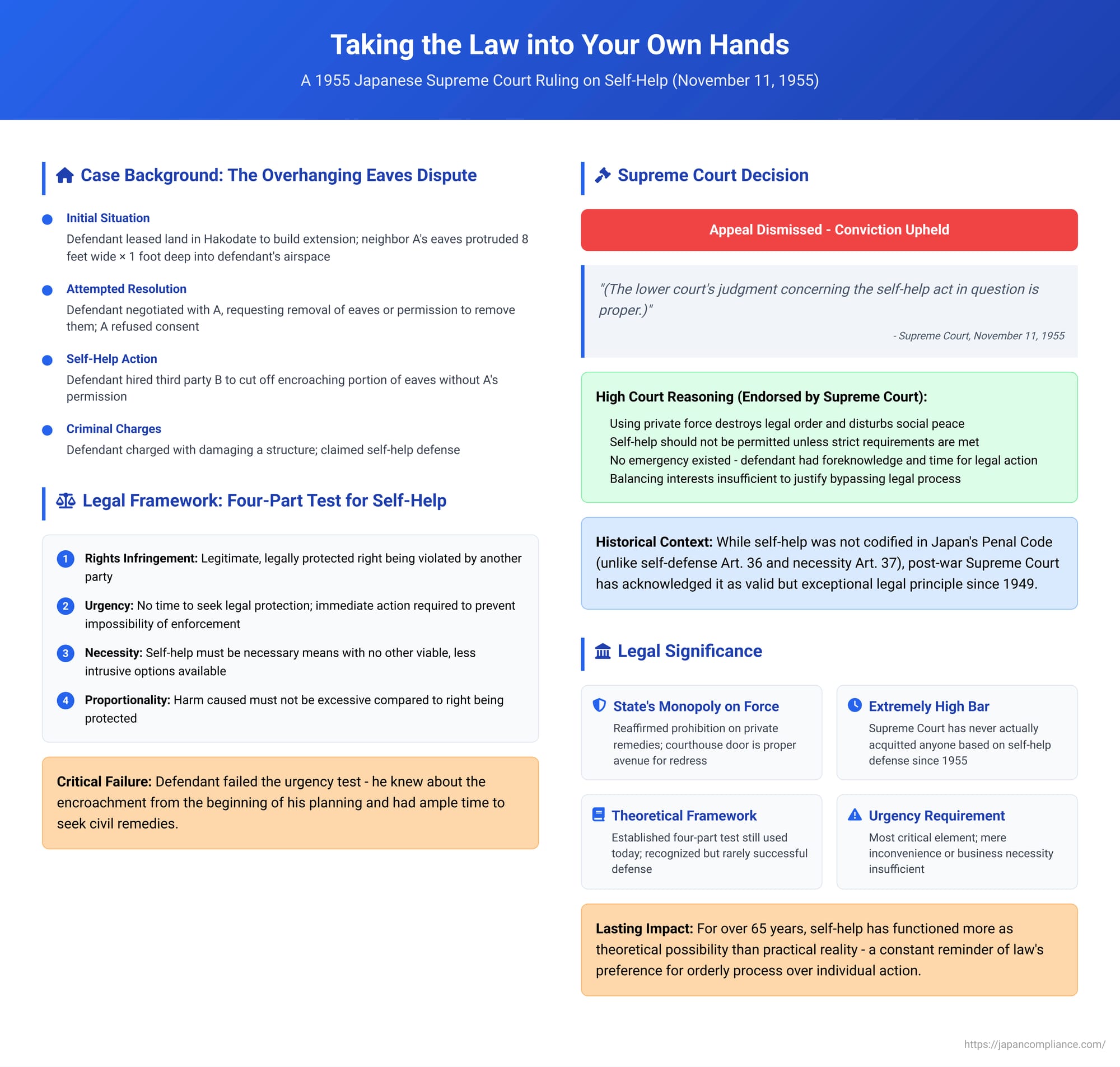

Taking the Law into Your Own Hands: A 1955 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Self-Help

Decision Date: November 11, 1955

A foundational principle of any modern legal system is the state's monopoly on the legitimate use of force. Citizens are expected to turn to courts and law enforcement to resolve disputes and protect their rights, not to resort to private enforcement. This prohibition on "self-remedy" is what separates the rule of law from anarchy. Yet, the law also recognizes that there can be exceptional, urgent circumstances where waiting for official intervention is not a viable option. This narrow exception is known as the doctrine of "self-help" (jikyū kōi), a legal concept that justifies taking matters into one's own hands to prevent the irreparable loss of a legal right.

On November 11, 1955, the Supreme Court of Japan issued a pivotal, albeit terse, decision in a case that perfectly illustrates the high bar for this doctrine. The case, involving a dispute over encroaching building eaves, did not result in an acquittal, but by endorsing the lower court's detailed reasoning, it helped to crystallize the strict conditions under which self-help might ever be considered a valid defense in Japanese criminal law.

The Factual Background: The Case of the Overhanging Eaves

The incident took place in the city of Hakodate. The defendant was leasing a parcel of land upon which he intended to build an extension to his property. He discovered a problem: the eaves of the entrance to his neighbor A's house were protruding over the boundary and into his leased airspace.

The defendant first attempted to resolve the issue through proper channels. He engaged in negotiations with A, requesting that A either remove the encroaching eaves or, failing that, give the defendant permission to remove them himself. A refused to consent.

Faced with this refusal, the defendant decided to take direct action. He hired a third party, B, who was unaware of the legal dispute, and instructed him to cut off the offending portion of A's eaves. A section measuring approximately 8 feet in width and 1 foot in depth was removed. As a result, the defendant was charged with the crime of damaging a structure.

The Lower Courts: A Firm Rejection of Private Force

The defendant was convicted at trial, and the conviction was upheld by the Sapporo High Court. The High Court's reasoning, which was later endorsed by the Supreme Court, is central to understanding the legal principles at play. The High Court made several key points:

- Primacy of the Legal Order: The court acknowledged that the eaves were indeed encroaching on the defendant's leased property. However, it declared that "even if this were an unauthorized and illegal construction by A as argued, using one's own force to eliminate the infringement without relying on legal remedies is a method of protecting rights that is utterly impermissible in our current form of state, as it destroys the legal order and disturbs the peace of society."

- Self-Help as a Non-Statutory Exception: The court stated that unless the strict requirements for legally codified defenses like self-defense or necessity are met, "an uncodified act such as self-help should not be permitted."

- Lack of Urgency: Crucially, the court found that the defendant was aware of the protruding eaves from the beginning of his own extension planning. This foreknowledge undermined any claim of a sudden, unforeseen emergency. The court explicitly found that the circumstances did not meet the test for self-help, which it defined as a situation where "there is no time to seek the protection of the law, and where, unless the act is done immediately, there is a risk that the realization of the claim will become impossible or markedly difficult."

- Balancing of Interests is Insufficient: The court considered the defendant's arguments that the extension was necessary to save his business from the brink of bankruptcy and that the damage to A's property was minor compared to the great benefit the defendant would receive. It dismissed these claims as insufficient to justify bypassing the legal process.

In essence, the High Court rejected the self-help claim primarily on the grounds that the situation lacked the requisite urgency.

The Supreme Court's Terse Endorsement

The defendant appealed to the Supreme Court, which dismissed the appeal in an extremely brief decision. The ruling itself contains little analysis, but it includes one critically important parenthetical statement:

"(The lower court's judgment concerning the self-help act in question is proper.)"

With this single phrase, the Supreme Court effectively adopted the High Court's entire reasoning as its own. While not a detailed opinion in itself, the 1955 decision thereby gave the nation's highest judicial imprimatur to the strict, urgency-focused framework for evaluating self-help claims.

The Doctrine of Self-Help (Jikyū Kōi) in Japanese Law

The 1955 ruling must be understood within the broader context of how Japanese law treats the concept of self-help.

An Uncodified Defense:

Unlike self-defense (Article 36) and necessity (Article 37), self-help is not explicitly defined in Japan's Penal Code. A 1940 draft revision of the penal code did include a provision for self-help, defining it as an act to prevent a legal claim from becoming "impossible or markedly difficult to execute" when it is not possible to receive timely legal assistance. However, this provision was dropped from later drafts, largely due to the difficulty of crafting an appropriately precise legal text.

The Evolution of Case Law:

Despite the lack of a statute, the post-war Supreme Court has acknowledged self-help as a valid, albeit exceptional, legal principle. This marked a shift from the pre-war era, when courts were generally hostile to the idea.

- A 1949 Supreme Court decision, concerning a food riot during the post-war food crisis, recognized the concept in theory. It defined self-help as an act by a right-holder to preserve a claim when there is "no time to wait for the hand of public authorities," giving the classic example of "a victim retrieving stolen goods at the scene of a theft."

- The 1955 eaves case reinforced this, showing the Court's willingness to consider self-help as a legal category, even while rejecting it on the facts.

- Finally, a 1971 Supreme Court decision explicitly stated that "self-help, along with self-defense and justifiable business acts, is a ground for precluding the illegality of a crime."

Despite this theoretical acceptance, to this day, the Supreme Court of Japan has never found a set of facts compelling enough to actually acquit a defendant based on a self-help defense.

The Four-Part Test for Self-Help:

From these cases and legal scholarship, a general four-part test for justifying a self-help act can be distilled:

- Infringement of a Right: There must be a legitimate, legally protected right that is being infringed upon by another party.

- Urgency (The Lack of Alternatives): This is the most critical hurdle. It must be demonstrated that seeking protection through official legal procedures (e.g., a court injunction) is not possible in a timely manner. The situation must be such that without immediate private action, the enforcement of the right would become impossible or at least extremely difficult.

- Necessity (Supplementarity): The act of self-help must be a necessary means to preserve the right in question. There must be no other less intrusive, viable options available.

- Proportionality (Appropriateness): The harm caused by the act of self-help must not be excessive in comparison to the right being protected. The means used must be reasonable and not violate public order or morals.

In the eaves case, the defendant's claim failed decisively on the second element: urgency. The High Court found that since he had known about the encroachment from the start of his planning, he had ample time to seek a civil remedy. There was no sudden crisis that made bypassing the courts necessary.

However, as some legal commentary has noted, one could construct an argument in the defendant's favor. If his business was truly on the verge of imminent collapse, and the extension was the only way to prevent it, a case for urgency and necessity could be made. If the financial devastation of bankruptcy far outweighed the cost of the damaged eaves, an argument for proportionality could also be advanced. This illustrates just how fact-dependent and narrowly construed the doctrine is.

Conclusion: A Principle Acknowledged in Theory, Elusive in Practice

The 1955 Supreme Court decision in the case of the overhanging eaves stands as a powerful reaffirmation of the state's authority and the prohibition on private remedies. While it implicitly accepted that self-help could, in theory, be a valid legal defense, its endorsement of the lower court's stringent application of the "urgency" requirement sent a clear message: the bar for justifying such actions is extraordinarily high. The ruling solidifies the principle that in a society governed by the rule of law, the courthouse door, not private force, is the proper avenue for redress. For over half a century since this decision, while the doctrine of self-help has remained a recognized part of Japan's legal landscape, it has functioned more as a theoretical possibility than a practical reality, a constant reminder of the law's deep-seated preference for orderly process over individual action.