Tackling Disinformation Online: Japan's Approach and Free Speech Considerations

TL;DR: Japan tackles online disinformation mainly through process-focused platform transparency and enhanced notice-and-takedown rules, sidestepping direct content bans to safeguard constitutional free speech. Businesses must strengthen moderation workflows, ad-screening, and disclosure compliance.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Nature and Impact of Online Disinformation in Japan

- Japan’s Current Regulatory and Self-Regulatory Framework

- Policy Debates and Directions: The MIC Study Group

- Freedom of Expression Considerations: A Balancing Act

- Implications for Businesses (Platforms and Advertisers)

- Conclusion

Introduction

The rapid spread of disinformation and misinformation across digital platforms presents a formidable global challenge, impacting everything from democratic processes and public health to financial stability and individual reputations. Japan, with its highly connected society and vibrant online sphere, is actively confronting this complex issue. However, crafting effective countermeasures requires navigating a delicate balance, weighing the need to mitigate the harms caused by false and misleading information against the deeply entrenched constitutional protections for freedom of expression.

Unlike illegal content such as defamation or copyright infringement, which have clearer legal boundaries and remedies (recently enhanced by revisions to Japan's law on intermediary liability), "disinformation" itself—information that is false but not necessarily illegal—occupies a more ambiguous space. Direct government regulation targeting the truthfulness of content raises significant concerns about censorship and the potential chilling of legitimate speech.

This article explores Japan's current approach to tackling online disinformation and misinformation. It examines the nature of the problem within the Japanese digital context, analyzes the existing legal and self-regulatory frameworks, discusses ongoing policy debates informed by recent events, and delves into the crucial free speech considerations that shape and constrain potential regulatory solutions.

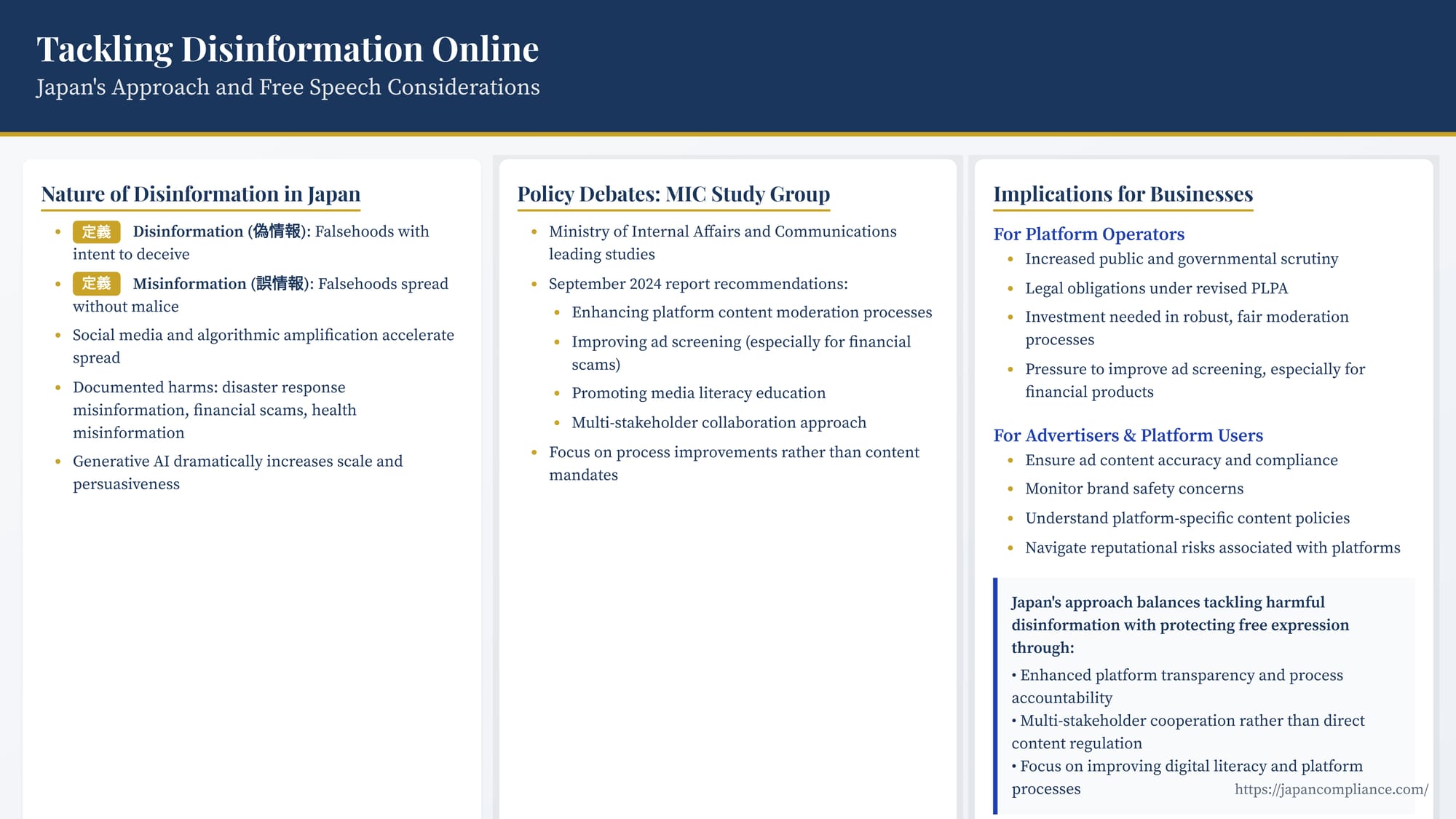

1. The Nature and Impact of Online Disinformation in Japan

Before examining regulatory approaches, it's essential to understand the specific contours of the disinformation challenge in Japan.

- Defining the Terms: Following common international usage, discussions in Japan often distinguish between:

- Disinformation (gijouhou): Information containing falsity, spread with the intent to deceive or mislead.

- Misinformation (gojouhou): Information containing falsity, spread without necessarily malicious intent (e.g., due to misunderstanding or error).

The term "Fake News" is also used, often referring specifically to disinformation presented in the style of legitimate news reporting. A particularly problematic recent phenomenon in Japan, as elsewhere, involves financially damaging "Fake Ads," especially investment scams using unauthorized likenesses of celebrities.

- Drivers of Spread in the Digital Space: The reasons for the rapid proliferation of false information online are multifaceted and mirror global trends, as analyzed by Japanese experts:

- Low Barrier to Entry: Social media platforms and user-generated content (UGC) models dramatically lower the cost and effort required to create and disseminate information widely, leading to information overload.

- Algorithmic Amplification: Platform algorithms, often designed to maximize user engagement and "attention" (the core of the "Attention Economy"), can inadvertently prioritize sensational, emotionally charged, or novel content, which often includes disinformation, over factual accuracy.

- Speed and Virality: Features like "likes," shares, and reposts enable false narratives to spread much faster and wider than corrections. Studies suggest novelty makes false information inherently more viral than truth.

- Psychological Factors: Cognitive biases, such as the "illusory truth effect" (repeated exposure making falsehoods seem more plausible) and the "continued influence effect" (misinformation persisting even after correction), make users susceptible to believing and retaining false information.

- Generative AI: The advent of sophisticated generative AI tools dramatically increases the potential scale, speed, and persuasiveness of disinformation campaigns.

- Documented Harms in Japan: The tangible negative consequences are increasingly recognized:

- Disaster Response: Following the Noto Peninsula Earthquake in early 2024, false rumors about rescue efforts and aid availability spread online, potentially hindering relief operations.

- Financial Scams: Widespread reports of sophisticated online investment scams using deepfaked images or unauthorized endorsements of famous personalities have led to significant financial losses for individuals.

- Public Health: Misinformation regarding vaccines or health treatments continues to pose challenges.

- Erosion of Trust: The constant exposure to potential falsehoods can erode trust in legitimate news sources, institutions, and even interpersonal communication online.

- Democratic Processes: While large-scale foreign interference like that seen in the US 2016 election hasn't been definitively proven to the same extent in Japan, concerns exist about the potential impact of disinformation on public opinion and political discourse.

2. Japan's Current Regulatory and Self-Regulatory Framework

Japan's current approach to online disinformation is characterized by limited direct legislative intervention targeting falsehoods per se, relying instead on a combination of existing laws applicable to specific harms, platform self-regulation, and recent efforts to enhance platform procedural transparency.

- Limited Direct Legislation on Falsehoods: Due to strong constitutional protections for freedom of expression (Article 21), Japan lacks a general law prohibiting the dissemination of "false information" as such. Unlike defamation (harm to reputation) or incitement (direct link to illegal action), falsity alone is generally not a basis for legal sanction against speech.

- Existing Relevant Laws: Certain specific types of harmful falsehoods are covered by existing laws:

- Public Offices Election Act: Prohibits spreading false information intended to influence election outcomes (Art. 235).

- Act against Unjustifiable Premiums and Misleading Representations: Prohibits false or misleading advertising regarding goods and services.

- Defamation/Libel (Civil Code Art. 709/710, Penal Code Art. 230): False statements harming reputation are actionable, but require proving specific harm and meeting legal standards (which include considerations of public interest and truthfulness defenses).

- Platform Self-Regulation (Content Moderation - CM): The primary mechanism for dealing with online disinformation currently rests with the digital platforms themselves. Major platforms (SNS, search engines, video sites) maintain their own terms of service and community guidelines that often prohibit certain types of disinformation (e.g., related to election integrity, public health, harmful conspiracies) even if the content isn't strictly illegal under Japanese law. Enforcement relies on the platform's own content moderation efforts, which typically involve a range of actions:

- Labeling potentially misleading content.

- Reducing the visibility or reach of such content (downranking).

- Removing content that violates specific policies.

- Suspending or banning users or accounts that repeatedly violate rules.

The effectiveness, consistency, and transparency of these self-regulatory efforts vary significantly across platforms and have been a major focus of public and governmental scrutiny.

- The Role of the Revised PLPA (Jouhou Platform Act) (Effective late 2024/early 2025): As discussed in the previous article, the 2024 revision of the Provider Liability Limitation Act imposes new duties on large designated platforms. While it does not mandate the removal of content solely because it is false or misleading (unless it also infringes specific legal rights like reputation), it does impact the disinformation landscape indirectly by requiring:

- Transparency of Moderation Policies (Art. 26): Platforms must publish clear criteria detailing what types of content violate their policies (including potentially their own rules against disinformation) and are subject to removal or other actions.

- Transparency of Actions (Art. 27-28): Platforms must generally notify users when their content is actioned and provide reasons, and publish annual transparency reports on their moderation activities.

- Implication: While not forcing removal of disinformation, these transparency requirements aim to make platforms more accountable for how they apply their own rules regarding such content, potentially leading to more consistent and understandable moderation practices.

3. Policy Debates and Directions: The MIC Study Group

The Japanese government, primarily through the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC), has been actively studying the disinformation problem via expert committees (like the kenzensei ken, "Study Group on Ensuring the Soundness of Information Distribution in the Digital Space"). Their September 2024 report (torimatome) provides insight into the likely direction of future policy efforts, which lean towards multi-faceted solutions rather than direct content bans:

- Enhancing Platform Content Moderation (Process Focus): Recommendations focus on improving the effectiveness and transparency of platforms' existing CM efforts, aligning with the goals of the revised PLPA. This includes clearer standards, more consistent application, and better communication with users.

- Improving Ad Screening: Particular emphasis is placed on tackling fraudulent advertising, especially financial scams. Recommendations include strengthening platforms' pre-screening processes for advertisements before they are distributed.

- Promoting Media Literacy: Recognizing that regulation alone cannot solve the problem, enhancing digital media literacy among citizens to help them critically evaluate online information is seen as crucial.

- Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration: Encouraging cooperation between platforms, traditional media outlets, independent fact-checking organizations, researchers, and government bodies to share information and develop best practices.

Importantly, the study group report reflects the prevailing caution regarding legislative measures that would mandate the removal of content based solely on its perceived falsity, due to the significant freedom of expression concerns.

4. Freedom of Expression Considerations: A Balancing Act

Any attempt to regulate disinformation directly confronts fundamental principles of free speech enshrined in Article 21 of Japan's Constitution.

- High Value of Free Speech: Japanese constitutional jurisprudence places a high value on freedom of expression as essential for individual self-realization and the functioning of democracy. Restrictions are subject to careful scrutiny.

- The "Marketplace of Ideas" Theory and its Critics: The traditional Western liberal theory, influential in Japan, posits that truth will eventually emerge from the free competition of ideas, and the best remedy for bad speech is "more speech," not censorship (state non-intervention). However, Japanese scholars, like their counterparts elsewhere, increasingly question whether this model holds true in the modern digital environment. They argue that factors like information overload, algorithmic manipulation driving engagement over accuracy (the "Attention Economy"), and the speed of viral falsehoods distort the "marketplace," potentially necessitating some form of intervention not to dictate truth, but to ensure the conditions for meaningful public discourse ("substantive" free speech).

- Prior Restraint Concerns (Jizen Yokusei): Content removal or blocking by platforms before content reaches its intended audience can be viewed as a form of prior restraint, which is subject to the strictest constitutional scrutiny in Japan (as established in cases like Hoppo Journal, Supreme Court, June 11, 1986). While platform CM is conducted by private entities, governmental pressure or mandates encouraging or requiring such actions raise complex questions about state involvement in potentially censorious activity. The revised PLPA attempts to sidestep this by focusing on process after a request is made or after content is posted, rather than mandating pre-publication filtering by the state. Nonetheless, the sheer scale of platform CM means vast amounts of content are effectively subject to a form of pre-distribution (or immediate post-distribution) review by platforms based on their own policies. Reconciling this reality with traditional prior restraint doctrine remains a theoretical challenge.

- The Difficulty of Defining "Truth" and "Falsity": Determining the objective truth or falsity of information, especially in complex political or scientific debates, is often difficult and contentious. Granting the state or even platforms broad power to adjudicate truth and remove "false" information risks suppressing dissenting opinions, satire, or simply information that turns out to be true later.

- Japan's Current Path: Process over Content: Reflecting these deep concerns, Japan's current legislative approach, exemplified by the revised PLPA, carefully avoids mandating removal based on falsity alone. It instead focuses on improving the processes surrounding content moderation (requester rights, sender notifications, policy transparency) for actions platforms already take based on illegality or their own terms of service. This suggests a policy choice prioritizing procedural fairness and transparency as the primary regulatory levers in this sensitive area, rather than attempting direct content regulation of non-illegal disinformation.

5. Implications for Businesses (Platforms and Advertisers)

The ongoing focus on disinformation and the related regulatory environment have practical consequences:

- For Platform Operators (Especially Large Designated Ones):

- Increased Scrutiny: Expect continued public and governmental scrutiny of content moderation policies and practices, particularly regarding harmful disinformation (scams, health misinformation, election interference).

- Transparency Obligations: Compliance with the revised PLPA's transparency requirements regarding moderation policies, actions, and reporting is now a legal mandate.

- Process Enhancements: Investment in robust, fair, and timely processes for handling takedown requests (for illegal content) and for applying internal policies (including those related to disinformation) is essential.

- Ad Screening Pressure: Significant pressure to improve vetting processes for advertisers and ad content, especially in high-risk areas like financial products, potentially requiring more resources and stricter standards.

- For Advertisers and Businesses Using Platforms:

- Ad Content Diligence: Increased need for advertisers to ensure their own content is accurate and compliant with both legal standards and evolving platform policies against misleading claims.

- Brand Safety: Greater awareness required regarding the types of content their advertisements might appear adjacent to, and potential use of brand safety tools or platform controls.

- Reputational Risk: Association with platforms perceived as being lax on disinformation or harmful content could pose reputational risks.

- Navigating Platform Policies: Understanding and complying with individual platform rules regarding specific types of content (e.g., health claims, political advertising, use of AI) becomes increasingly important.

Conclusion

Japan is actively navigating the complex challenge of online disinformation, seeking solutions that protect users and democratic processes without unduly infringing upon the vital constitutional right to freedom of expression. Unlike approaches centered on direct state regulation of false content, Japan's current strategy emphasizes enhancing the procedural accountability and transparency of the large digital platforms that mediate online information flows.

The recent revision of the Provider Liability Limitation Act (now the Jouhou Platform Taisho Hou) exemplifies this approach, mandating clearer processes for content removal requests and greater transparency regarding platforms' own moderation rules and actions. While not directly targeting disinformation unless it infringes specific rights, these measures aim to foster a more responsible and understandable online environment.

Policy debates continue, particularly concerning issues like fraudulent advertising and the potential impact of disinformation on national security and elections. Future regulatory developments are likely to focus on further strengthening platform processes, promoting media literacy, and encouraging multi-stakeholder cooperation, rather than embarking on direct content censorship.

For businesses operating in this space, the landscape demands a proactive approach. Platforms must invest in transparent and fair moderation systems, while advertisers and companies utilizing platforms need to be vigilant about their own content and associations. The delicate balance between combating online harms and safeguarding free speech remains central to Japan's evolving digital governance framework, requiring continuous monitoring and adaptation by all stakeholders.

- Content Moderation and Intermediary Liability in Japan: Understanding the Revised Provider Liability Act

- Japan’s Evolving Platform Regulation Landscape: An Overview for Global Businesses

- Online Defamation as Customer Harassment in Japan

- MIC Study Group on Sound Information Distribution — 2024 Final Report (JP)

https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_sosiki/kenkyu/johotech2024/index.html