Swinging the Sword: How a Threat Becomes a Physical Assault in Japanese Law

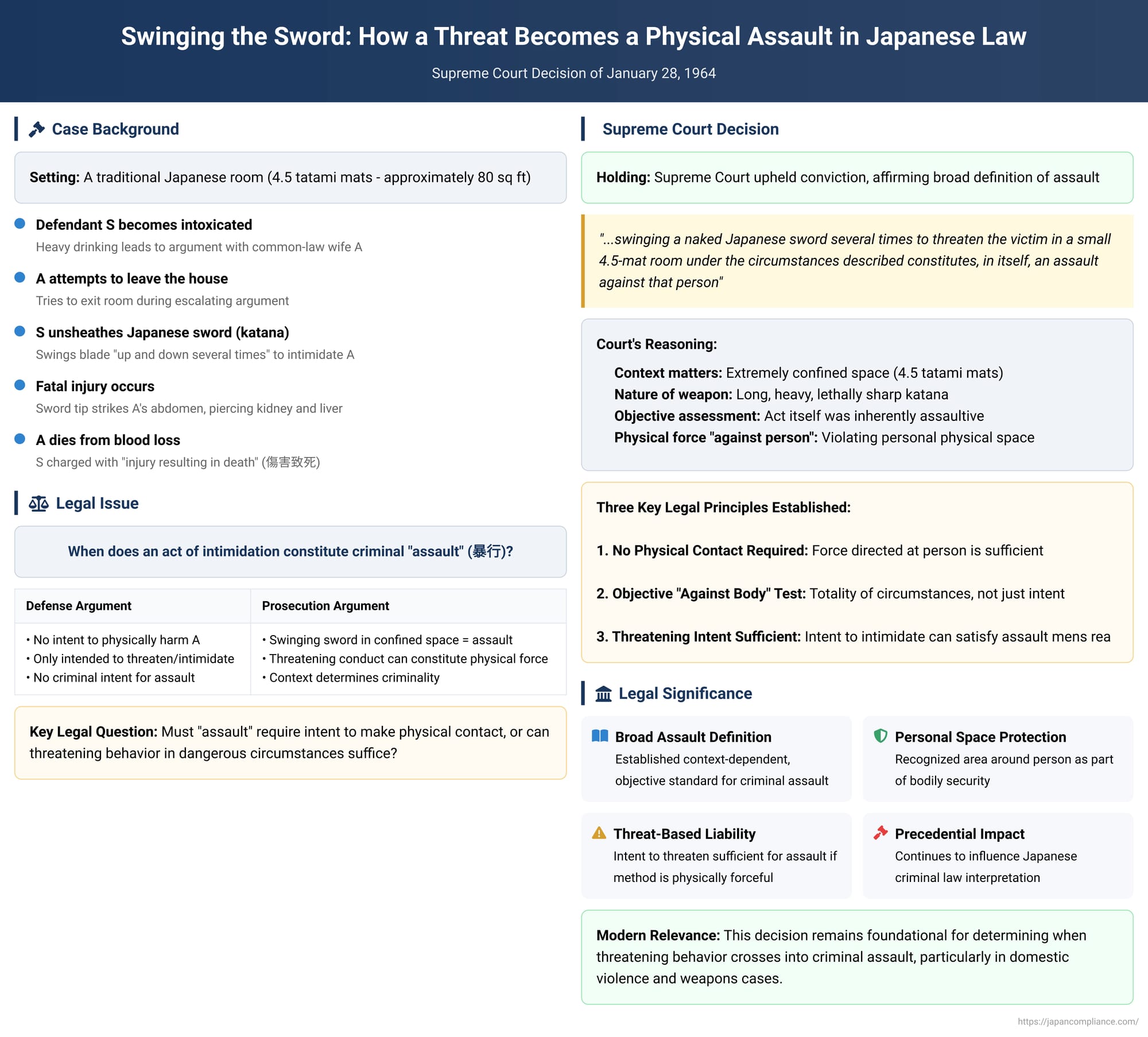

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Decision of January 28, 1964. Case No. (A) 2048 of 1961.

Introduction

Imagine a small room, barely 80 square feet. An intoxicated man, in a fit of rage, unsheathes a glittering Japanese sword, a katana. He doesn't intend to strike his common-law wife, who is trying to leave, but only to threaten her, to stop her in her tracks. He swings the naked blade in the cramped space. In a moment, his threat tragically materializes into a fatal injury. This dramatic and grim scenario was at the heart of a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on January 28, 1964. The case forced the judiciary to answer a fundamental question at the core of criminal law: When does an act of pure intimidation, without the specific intent to make physical contact, cross the line to become a physical "assault"?

The Court's answer solidified a broad and objective definition of assault that continues to influence Japanese jurisprudence. The ruling is a powerful exploration of the legal boundary between a menacing gesture and a criminal act, demonstrating that in the eyes of the law, the context, proximity, and nature of the force used can transform a threat into an unlawful attack, regardless of the actor's ultimate intention. This article delves into the facts of this pivotal case and the complex legal debates it brings to light about the very meaning of assault.

The Fatal Encounter: Factual Background

The events unfolded in the defendant's home. The defendant, S, was drinking heavily and became intoxicated. When his common-law wife, A, returned home, he began to lash out at her in a drunken tirade. As the argument escalated, A attempted to leave the room and exit the house.

Determined to stop her, S reached for a nearby Japanese sword. He unsheathed the blade and, in his own words, swung it up and down several times in front of her to intimidate her into staying. The setting for this act was a crucial factor: a traditional Japanese room of just 4.5 tatami mats, a space so small that any significant movement with a long weapon would inevitably command the entire area.

During this act of brandishing the sword, the defendant lost control. The sharp tip of the blade struck A, piercing her abdomen. The resulting wound, a stab wound to her kidney and liver, caused massive blood loss, and A died from her injuries. S was subsequently charged with "injury resulting in death" (shōgai chishi), a crime that requires proving an initial act of assault which then leads to an unintended, fatal result. The entire case, therefore, hinged on whether his act of swinging the sword could be legally classified as an "assault."

The Lower Court's Finding and the Supreme Court's Terse Affirmation

The defense argued that S never intended to harm A. His "criminal intent," they claimed, did not extend to striking her body; he only swung the sword in her presence to frighten her. Therefore, the foundational element of an "assault" was missing.

The Tokyo High Court, hearing the case on appeal, disagreed. It found that the defendant, intending to stop A from leaving, "thought to threaten her by unsheathing and swinging a Japanese sword in front of her eyes." The court concluded:

"...swinging a naked Japanese sword several times to threaten A in a small 4.5-mat room, as in the facts presented, must be described as, in and of itself, an assault against that person."

The High Court held that the act itself, given the context, was an assault. The intent to threaten was sufficient to establish the intent for this assault. With the assault established, the unintentional death that followed completed the crime of injury resulting in death.

The case then went to the Supreme Court of Japan. The Court's final decision was remarkably brief, dismissing the appeal primarily on procedural grounds. However, it included a short, parenthetical statement that would become its lasting legacy:

"(...the High Court's judgment that swinging a naked Japanese sword several times to threaten the victim in a small 4.5-mat room under the circumstances described constitutes, in itself, an assault against that person, is correct.)"

With this single sentence, the nation's highest court gave its full endorsement to a broad, context-dependent definition of assault. It affirmed that an act of intimidation can, by its very nature, be a physical assault, setting a precedent that has been analyzed and debated ever since.

Deconstructing "Assault" (Bōkō): The Core of the Legal Debate

The 1964 ruling is significant because it touches upon several fundamental and contested issues within the legal definition of "assault" (bōkō). Under Article 208 of the Japanese Penal Code, assault is generally defined as the "unlawful use of physical force against a person's body." But what does this phrase truly mean? The 1964 case serves as a perfect lens through which to examine three central debates.

1. The Question of Physical Contact: Must Force Touch the Body?

A primary point of contention in assault law is whether the defendant's use of force must make actual physical contact with the victim.

The dominant view in Japanese law, supported by numerous court precedents, is that contact is not necessary. This perspective holds that an unlawful use of force directed at a person is an assault, even if it misses. Examples from case law include throwing a stone that flies past the victim's head, or aggressively driving a car so close to a pedestrian as to cause alarm. The rationale is that criminal liability should not depend on the victim's good fortune or skill in dodging the attack. The crime is in the unlawful act of projecting force against the person.

A minority of legal scholars, however, argue for a strict "contact requirement," believing that without a physical touching, the crime is not complete.

The 1964 sword case stands as a powerful affirmation of the dominant, no-contact-required position. Even if one were to hypothetically accept the defendant's claim that he was only swinging the sword in front of his wife, the act of propelling a deadly weapon through the air in such close proximity to her was deemed a sufficient use of "physical force against a person." The space around a person is considered part of their bodily security, and violently intruding upon it with force can constitute an assault.

2. The Direction of the Force: What Does "Against the Body" Mean?

The defense argued that the force was not directed "against" A's body, but merely in her presence. This raises the question of how the law determines the target of a physical force.

The legal consensus, solidified by this case, is that the determination is not based solely on the defendant's subjective state of mind but on an objective assessment of the totality of the circumstances. The factors considered include:

- Proximity: The act occurred in an extremely confined space, making the distinction between "in front of" and "at" almost meaningless.

- The Nature of the Force: The force was not trivial. It involved a long, heavy, and lethally sharp weapon being swung with enough energy to be uncontrollable.

- The Inevitable Result: The fact that the sword did ultimately strike the victim, even if claimed to be accidental, serves as powerful evidence of the inherent direction of the force against her.

Some legal theories even conceptualize the "body" as extending to the immediate physical space surrounding a person. An attack on this personal sphere is an attack on the person. Swinging a katana within inches of someone in a tiny room is a quintessential violation of this personal space. Therefore, the court had little trouble concluding that the defendant's actions constituted force "against the person's body."

3. The Role of "Danger": Must an Assault Carry a Risk of Injury?

Another deep theoretical divide in Japanese assault law is whether the act must carry a concrete "danger of causing injury" to qualify as assault.

One school of thought argues that danger is a necessary element. This view understands the crime of assault as being fundamentally a form of attempted injury. For an act to be a criminal assault, it must create a tangible risk of physical harm. Proponents of this view would readily support the 1964 decision, as swinging a sword in a small room is self-evidently an act fraught with the danger of causing serious injury. Many court decisions involving non-contact assaults, such as high-speed car chases, explicitly reference the "danger" created by the act as a reason for classifying it as an assault.

However, another influential school of thought argues that danger of injury is not an essential element of assault. This perspective sees assault as a distinct crime protecting a person's physical integrity and security from any unlawful application of force, whether it is dangerous or not. They argue that requiring danger would mean that a non-dangerous but offensive touching (e.g., spitting on someone, grabbing their clothes without force) might not be considered an assault, leaving a gap in the law. According to this view, the law already filters out truly trivial acts through the doctrine of de minimis non curat lex (the law does not concern itself with trifles).

While the 1964 case involved an obviously dangerous act, its core reasoning—that the act of swinging the sword was in itself an assault—aligns with the broader interpretation. It focuses on the unlawful application of significant physical force in a threatening manner, rather than grounding its decision solely on a calculation of risk.

The Implications of the 1964 Ruling

The Supreme Court's decision in the sword case had significant implications. It cemented a broad, objective standard for assault in Japanese criminal law. It established that the intent required for assault (bōkō no koi) can be satisfied by the intent to threaten, so long as the act used to carry out that threat is an unlawful physical force directed against a person.

This principle is especially critical for "result-qualifying crimes" like injury resulting in death. For such a charge to succeed, the prosecution must prove a foundational crime of assault that led to a more severe, unintended outcome. The 1964 ruling clarifies that a defendant cannot escape liability by claiming they "only meant to scare" the victim if the method of scaring them was, by objective standards, a physical assault. S intended the menacing swing—the assault—and that assault unintentionally caused death. This two-step logic completes the elements of the crime.

Conclusion

The legacy of the 1964 Supreme Court decision is its clear and uncompromising answer to the question of when a threat becomes a crime of physical violence. It teaches that the law does not operate in a vacuum; it evaluates actions within their full context. The image of a sword being swung in a 4.5-mat room has become a powerful legal metaphor. It represents an act so inherently violent, so intrusive upon a person's physical security, and so directed at the victim by virtue of its environment, that the law cannot interpret it as anything less than an assault. The ruling serves as a stark reminder that in the enclosed spaces of human conflict, the line between a gesture and an attack can be as thin as the edge of a blade.