Japan Supreme Court 2023 Pension‑Cut Ruling: Balancing Sustainability and Recipient Rights

TL;DR

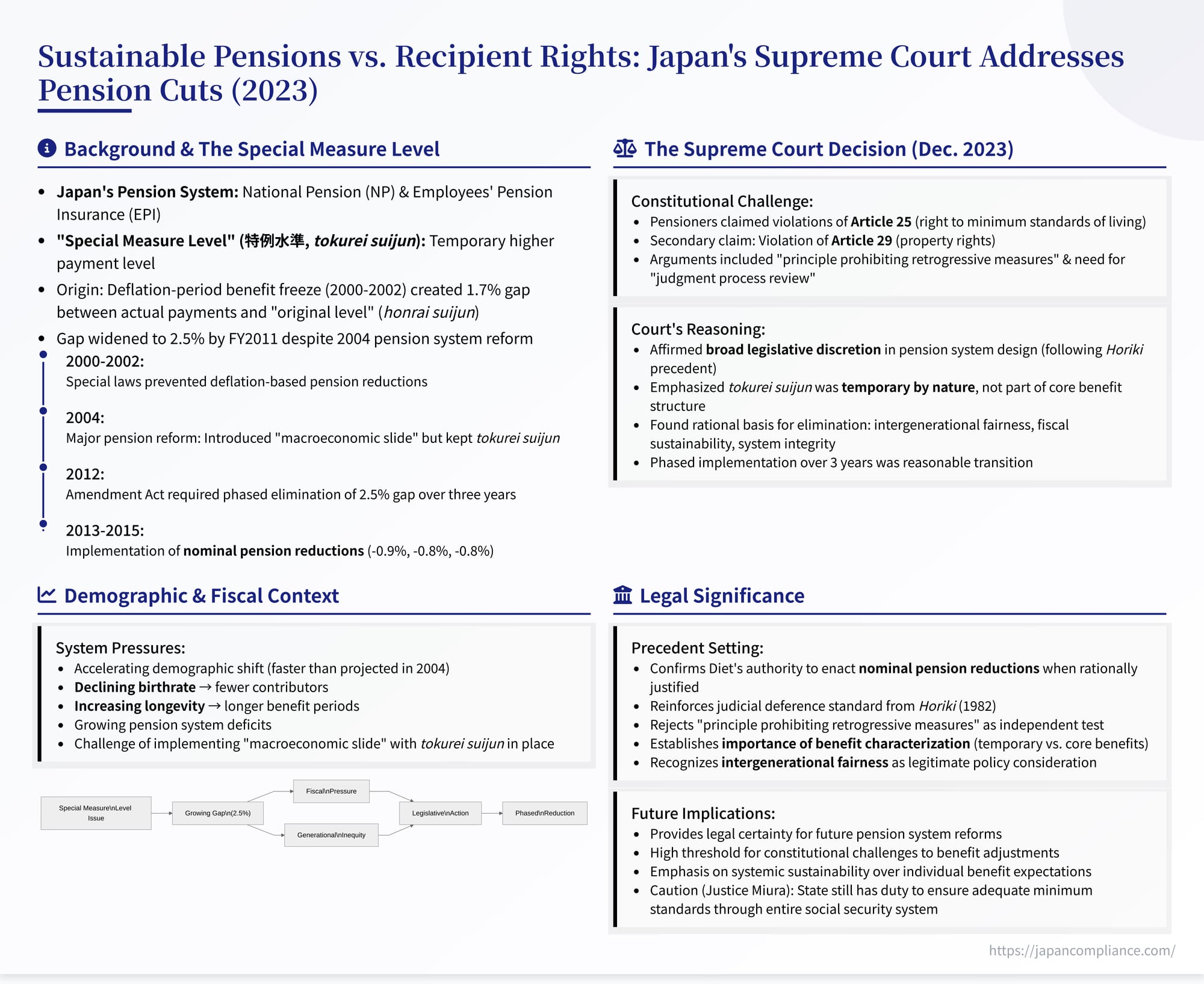

- In December 2023 Japan’s Supreme Court upheld the 2012 law phasing out a 2.5 % “special‑measure” pension surplus.

- The Court applied the Horiki standard: legislation is invalid only if “markedly irrational.”

- Key justifications: inter‑generational fairness, fiscal sustainability, and restoring the macro‑economic slide.

- Challenges based on Articles 25 & 29, non‑retrogression, and process review were all rejected.

- Ruling signals broad Diet discretion to trim anomalous benefits while preserving Article 25 minimum‑standard duties.

Table of Contents

- Background: Japan’s Pension System and the “Special Measure Level”

- The 2012 Amendment Act and the Legal Challenge

- The Supreme Court’s Decision: Upholding the Reductions

- Significance and Analysis

- Conclusion

The long-term sustainability of public pension systems is a pressing concern for many aging societies worldwide. Balancing the promises made to current and future retirees with fiscal realities and intergenerational fairness often necessitates difficult reforms, including potential reductions in benefit levels. How courts review the legality and constitutionality of such reductions is a critical question. A recent landmark decision from Japan's Supreme Court, issued on December 15, 2023, provides significant insights into this issue within the Japanese context. This case, formally the Case Concerning Request for Revocation of Pension Reduction Revision Decision, etc. (Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, Reiwa 4 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 275), addressed the constitutionality of a legislative act that phased out a temporary, higher level of pension payments, resulting in nominal benefit cuts for many retirees.

Background: Japan's Pension System and the "Special Measure Level"

Japan operates a complex public pension system, primarily consisting of the National Pension (NP, Kokumin Nenkin), providing the Old-Age Basic Pension to all residents, and the Employees' Pension Insurance (EPI, Kōsei Nenkin Hoken), providing earnings-related benefits (Old-Age Employees' Pension) to salaried workers. These systems largely operate on a pay-as-you-go basis, meaning current workers' contributions primarily fund current retirees' benefits.

To maintain the real value of pensions, Japan introduced a "price slide system" (bukka suraido sei) in 1973. This mechanism automatically adjusted pension amounts based on changes in the national Consumer Price Index (CPI).

However, during a period of deflation in the early 2000s, the government intervened. Special legislation (collectively termed the "Price Slide Special Measures Acts," Bukka Suraido Tokurei Hō) was enacted for Fiscal Years (FY) 2000, 2001, and 2002. These laws froze pension benefit levels at the FY1999 amount, preventing the downward adjustments that would have occurred under the normal price slide system due to falling prices.

This freeze created a discrepancy. The actual amount paid to pensioners (termed the "special measure level," 特例水準, tokurei suijun) became higher than the amount they should have received had the normal price indexation been applied (termed the "original level," 本来水準, honrai suijun). By the end of FY2002, this gap reached approximately 1.7%. Further special legislative measures in FY2003 and FY2004 involved nominal benefit reductions (reflecting continued deflation) but were designed to preserve this 1.7% gap, meaning pensions continued to be paid at a level higher than mandated by the underlying price indexation rules.

The 2004 Pension Reform Act (Heisei 16nen Kaiseihō) brought significant changes. It formally abolished the old price slide system and introduced a new indexation mechanism based on changes in prices and wages. Critically, it also introduced the "macroeconomic slide" (makuro keizai suraido sei). This mechanism was designed to automatically restrain future benefit increases (during periods of price/wage growth) by factoring in demographic changes – specifically, the decline in the number of contributors (due to falling birthrates) and the increase in life expectancy (longevity). This was intended to ensure the long-term fiscal balance and sustainability of the pension system under fixed contribution rates.

However, the 2004 Act did not immediately eliminate the tokurei suijun. Instead, it established a mechanism for its gradual resolution: the tokurei suijun level would be frozen, and only when inflation caused the honrai suijun (calculated under the new rules) to naturally rise and surpass the frozen tokurei suijun would the gap be closed. Furthermore, the macroeconomic slide mechanism was explicitly not to be applied to pensions as long as they were being paid at the tokurei suijun.

Unfortunately, due to continued periods of low inflation or deflation after 2004, the honrai suijun never caught up. The tokurei suijun persisted, and the gap actually widened, reaching approximately 2.5% by FY2011. Compounding the issue, updated fiscal projections released around 2010 indicated that Japan's demographic shift (declining birthrate, increasing longevity) was proceeding even faster than anticipated in 2004, and the pension system's finances were facing increasing deficits.

This situation – a persistent, unintended higher level of benefit payments coupled with worsening long-term fiscal prospects – prompted further legislative action.

The 2012 Amendment Act and the Legal Challenge

In 2012, the Diet enacted the "Act for Partial Revision of the Act for Partial Revision of the National Pension Act, etc." (平成24年改正法, Heisei 24nen Kaiseihō, hereinafter "2012 Amendment Act"). Article 1 of this Act specifically addressed the tokurei suijun. It mandated the phased elimination of the 2.5% gap over three fiscal years: FY2013, FY2014, and FY2015. The reduction was scheduled to occur in steps (-0.9% in Oct 2013, -0.8% in Apr 2014, -0.8% in Apr 2015), regardless of whether prices or wages increased during FY2013 or FY2014. This meant nominal reductions in the monthly pension checks received by retirees.

A group of retirees receiving Old-Age Basic Pension and/or Old-Age Employees' Pension (the Appellants) were subject to these reductions based on individual revision decisions issued by the MHLW Minister. They challenged these decisions, arguing that the underlying legislative provision mandating the elimination of the tokurei suijun (Article 1 of the 2012 Amendment Act, referred to by the Court as "the provision at issue," honken bubun) was unconstitutional.

Their main claims were that the provision violated:

- Article 25 (Right to minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living)

- Article 29 (Right to property – arguing the pension right was a form of property being infringed)

They also invoked related constitutional arguments, including the principle prohibiting retrogressive measures in social security (arguing that once a standard is set, it cannot be lowered without strong justification) and advocating for the application of "judgment process review" (a standard typically used for administrative discretion) to scrutinize the legislative process itself.

After lower courts dismissed their claims, the case reached the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding the Reductions

On December 15, 2023, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court unanimously dismissed the appeal, finding the challenged provision of the 2012 Amendment Act constitutional under both Article 25 and Article 29.

1. Reasoning on Constitutionality (Articles 25 & 29):

The Court's core reasoning centered on the concept of legislative discretion in social security matters, heavily referencing the principles established in the 1982 Horiki decision.

- Broad Legislative Discretion Affirmed: The Court reiterated that designing and modifying the pension system falls within the broad discretion of the Diet. This is because:

- The goals of Article 25 are realized through specific legislation.

- Determining "minimum standards" is complex and relative.

- Pension system design requires consideration of numerous, multifaceted factors: socio-economic conditions, demographic trends, fiscal realities (including pension finances), financial policy, living standards, interaction with other social programs, system stability and trust, public opinion, and importantly, fairness between generations (sedai-kan no kōhei).

- Assessing these factors and making policy judgments involves specialized expertise and political negotiation, making it inherently a task for the political branches (the Diet) within the framework of democratic processes and the separation of powers.

- Standard of Review (Horiki Standard): Therefore, judicial review of such legislative choices is highly deferential. Courts should only intervene if the legislation is markedly lacking in rationality and constitutes a clear deviation from or abuse of legislative discretion.

- Nature and Origin of the Tokurei Suijun: The Court emphasized the specific history of the tokurei suijun. It was not part of the originally designed benefit structure but arose from ad hoc special laws freezing benefits during an unusual period of deflation. The Court stated that, given this origin, the tokurei suijun was intended from the outset to be temporary and eventually eliminated. It represented a level of payment above the one justified by the system's own indexation rules at the time.

- Justification for Eliminating the Tokurei Suijun: The Court found several rational justifications for the Diet's decision in 2012 to eliminate this temporary level:

- Intergenerational Fairness: Maintaining the tokurei suijun indefinitely would force current workers (under the pay-as-you-go system) to bear a burden exceeding what was required to fund the "original level" benefits, essentially subsidizing past legislative choices. It would also deplete resources needed for when current workers retire.

- Fiscal Sustainability: By 2012, projections clearly showed accelerating aging and declining birthrates, alongside growing pension deficits. Eliminating an artificially inflated benefit level was a rational step towards mitigating fiscal deterioration and ensuring the long-term sustainability of the entire system.

- Public Trust: Persistently paying benefits above the system's own rules could undermine public trust in the pension system's fairness and viability.

- Enabling Macroeconomic Slide: Resolving the tokurei suijun was a prerequisite for applying the macroeconomic slide mechanism, which was itself designed as a rational tool for ensuring long-term balance and intergenerational equity in the face of demographic pressures.

- Rationality of the Measure: Considering these factors – the temporary/anomalous nature of the tokurei suijun, the principle of intergenerational fairness, the need for fiscal sustainability and public trust, and the connection to implementing the macroeconomic slide – the Court concluded that the legislative decision to eliminate the tokurei suijun uniformly over three years was not irrational.

- Conclusion on Articles 25 & 29: Since the legislative action was found to be within the Diet's broad discretion and not markedly irrational, it did not violate Article 25. Regarding Article 29 (property rights), the Court viewed the appellants' claim as substantively similar to the Article 25 claim, given the nature of statutory pension rights which are subject to legislative modification for public welfare purposes. Citing precedents (including Horiki and cases on property rights regulation), it found no unreasonable restriction on vested pension rights that would constitute a violation of Article 29. The Court explicitly stated that its conclusion was evident based on the principles of these prior Grand Bench decisions.

2. Addressing Other Arguments (via Supplementary Opinions):

While the main opinion focused on the Horiki standard, two concurring Justices provided supplementary opinions addressing other arguments raised by the appellants, reinforcing the majority's conclusion.

- Prohibition Against Retrogressive Measures: Justice Ojima directly tackled the argument that Article 25(2)'s mandate for the state to "strive for the promotion and extension" of social security implies a "principle prohibiting retrogressive measures" (seido kōtai kinshi gensoku). He found this principle, as argued, to be underdeveloped and ambiguous in Japanese constitutional law. He questioned what constitutes "retrogression" (is any reduction automatically suspect?) and how such a principle interacts with the hierarchy between the Constitution and statutes. He concluded it was not currently a mature or appropriate independent standard for judicial review of legislation like the 2012 Act. The mere fact that benefits were reduced did not, in his view, automatically trigger a stricter standard of review under this purported principle.

- Legislative Judgment Process Review: Justice Ojima also rejected the appellants' call to apply "judgment process review" (handan katei shinsa)—a doctrine used to scrutinize the reasoning process behind administrative discretionary decisions—directly to legislative acts. He argued that judicial review of legislation's constitutionality primarily examines the objective normative content of the law and its compatibility with the Constitution. It does not typically involve a direct assessment of the adequacy of the legislative process itself (e.g., whether the Diet sufficiently considered all relevant facts or debated thoroughly), distinguishing it from the review of specific administrative actions where procedural rationality is often key. While courts consider legislative facts to understand a law's purpose and effect, this is different from scrutinizing the legislative deliberation process itself as a direct test of constitutionality. Since the normative content of the 2012 Act was deemed reasonable, examining the legislative process through this lens was unnecessary.

- Acknowledging Hardship: Justice Miura, while concurring with the outcome, added a note of caution. He acknowledged that pension reductions inevitably cause hardship, especially for those with limited other resources, pointing to the increasing number of elderly households receiving public assistance. He stated that while the legislative decision was constitutionally permissible given the specific circumstances (temporary nature of tokurei suijun, sustainability needs), the state's broader duty under Article 25 remains. This duty requires ensuring minimum standards through the entire social security system (pensions, healthcare, welfare, public assistance) and necessitates ongoing efforts to provide adequate support and smooth access to necessary benefits for those facing hardship.

Significance and Analysis

The 2023 Supreme Court decision carries substantial weight for the future of social security law and constitutional interpretation in Japan:

- Upholding Legislated Pension Cuts: It represents a significant affirmation of the Diet's authority to enact legislation that results in nominal reductions to existing public pension benefits, provided there is a rational basis grounded in public welfare concerns like fiscal sustainability and intergenerational equity.

- Importance of Benefit Characterization: The Court's emphasis on the tokurei suijun's origin as a temporary, anomalous level, distinct from the core, rule-based benefit calculation, was crucial to its finding of rationality. This suggests that future attempts to reduce "core" or standard benefit levels might face different scrutiny, though the Horiki standard of broad discretion would still likely apply.

- Reinforcement of Judicial Deference: The ruling strongly reinforces the Horiki precedent of judicial deference to legislative policy choices in the complex domain of social security. The threshold for finding such legislation unconstitutional ("markedly lacking in rationality," "clear abuse of discretion") remains exceedingly high.

- Rejection of Non-Retrogression / Legislative Process Review: The explicit rejection (in supplementary opinions) of the non-retrogression principle and the direct application of judgment process review to legislation further narrows the potential avenues for constitutional challenges to social security reforms that involve benefit adjustments. The focus remains firmly on the rationality of the legislative outcome (the law's normative content) rather than the quality of the legislative process or a strict prohibition on reducing benefit levels.

- Implications for Future Reforms: This decision provides a degree of legal certainty for policymakers contemplating adjustments to social security benefits in response to ongoing demographic pressures and fiscal challenges. It confirms that measures aimed at ensuring long-term sustainability and fairness between generations, even if involving reductions from previously higher (potentially anomalous) levels, are likely to be considered within the Diet's constitutional powers. However, Justice Miura's opinion serves as a reminder of the underlying constitutional duty to ensure adequate minimum standards through the system as a whole.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's December 2023 judgment concluded that the phased elimination of the temporary "special measure level" of public pension payments, mandated by the 2012 Amendment Act, was a constitutional exercise of legislative discretion. The Court found the measure rational in light of its purpose: rectifying an anomaly, ensuring intergenerational fairness, bolstering fiscal sustainability, and enabling the proper functioning of the pension system's adjustment mechanisms like the macroeconomic slide. By reaffirming the Horiki standard of broad legislative discretion and limited judicial review, and declining to adopt stricter standards like the non-retrogression principle or legislative process review, the decision underscores the primary role of Japan's political branches in navigating the complex trade-offs inherent in maintaining a viable social security system for an aging society. While upholding the specific reduction, the judgment implicitly acknowledges the ongoing challenge of meeting the substantive goals of Article 25 through the combined efforts of various social programs.