Surrogacy Across Borders: Japan's Supreme Court on Legal Motherhood and Foreign Judgments

Date of Decision: March 23, 2007, Supreme Court of Japan (Second Petty Bench)

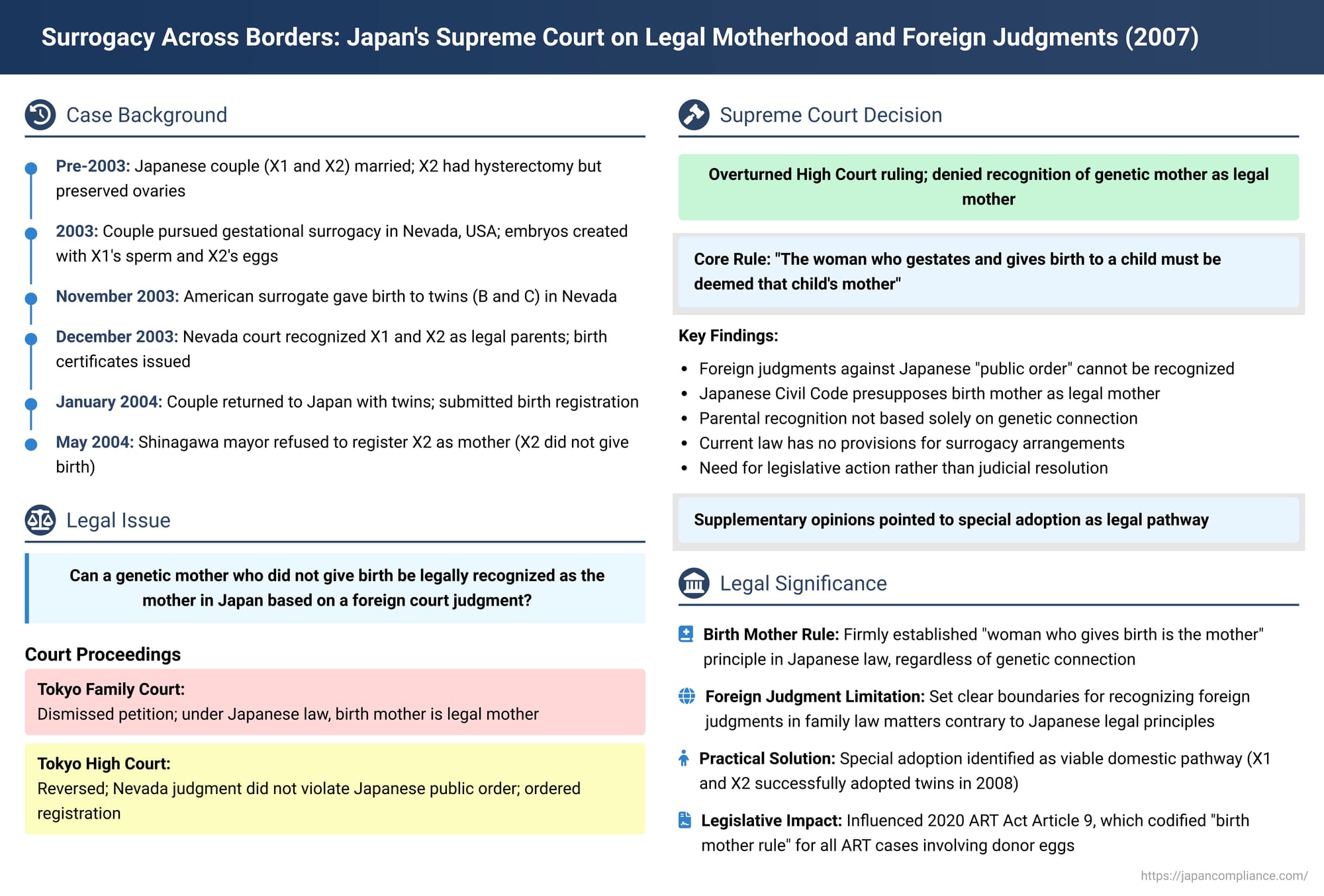

Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) have revolutionized family building, offering hope to many who cannot conceive naturally. However, methods like surrogacy, particularly when they involve international arrangements, often create intricate legal quandaries regarding the determination of parentage. A landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on March 23, 2007, confronted such a scenario, delivering a crucial judgment on legal motherhood in the context of gestational surrogacy and the recognition of foreign court orders in Japan.

The Facts: A Japanese Couple's Journey to Parenthood via US Surrogacy

The case involved X1 (husband) and X2 (wife), a married Japanese couple. X2 had undergone a hysterectomy due to cervical cancer, rendering her unable to carry a pregnancy. However, her ovaries had been preserved, allowing for the possibility of using her own eggs for conception.

In 2003, the couple pursued gestational surrogacy in the United States. Embryos were created using X2's eggs and X1's sperm. These embryos were then implanted into the uterus of A, an American woman residing in Nevada, who had entered into a paid surrogacy agreement with X1 and X2. In November 2003, A gave birth to twins, B and C, in Nevada.

Following the birth, in December 2003, a Nevada state court, acting on a petition by X1 and X2, issued a judgment. This judgment recognized X1 and X2 as both the genetic and legal parents of the twins, B and C. Subsequently, the State of Nevada issued birth certificates for B and C, officially listing X1 as the father and X2 as the mother.

In January 2004, X1 and X2 returned to Japan with the twins. They submitted a birth registration to Y, the mayor of Shinagawa Ward in Tokyo, seeking to register B and C as their legitimate children, with X1 as the father and X2 as the mother. However, in May 2004, Mayor Y issued a disposition refusing to accept the birth registration. The grounds for refusal were that there was no factual evidence of X2 having given birth to the children, and consequently, a legitimate parent-child relationship between X1/X2 and B/C could not be recognized under Japanese law.

Navigating the Japanese Legal System: Lower Court Battles

X1 and X2 challenged the ward mayor's decision by petitioning the Tokyo Family Court to order the acceptance of the birth registration.

- Tokyo Family Court: The Family Court dismissed the couple's petition. It determined that Japanese law was the governing law for establishing parentage in this case. Under the prevailing interpretation of the Japanese Civil Code, the legal mother is considered to be the woman who gives birth to the child. Since X2 had not given birth to B and C, the court found the ward mayor's refusal to register her as the mother to be lawful.

- Tokyo High Court: X1 and X2 appealed to the Tokyo High Court, which reversed the Family Court's decision. The High Court found that recognizing the Nevada court's judgment, which declared X1 and X2 as the legal parents, would not substantially violate Japanese "public order or good morals" (公序良俗 - kōjo ryōzoku). The High Court applied, or analogously applied, Article 118 of Japan's Code of Civil Procedure (which governs the recognition of foreign court judgments). It concluded that as a result of recognizing the foreign judgment, B and C were confirmed as the children of X1 and X2. Therefore, it ordered the ward mayor to accept the birth registration.

The ward mayor, Y, then sought and was granted permission to appeal the High Court's ruling to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (March 23, 2007)

The Supreme Court unanimously overturned the Tokyo High Court's decision, thereby upholding the Family Court's original ruling and the ward mayor's refusal to accept the birth registration as submitted.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was multifaceted:

Key Principle 1: Recognition of Foreign Judgments and Public Order

The Court first addressed the conditions for recognizing a foreign court judgment in Japan under Article 118 of the Code of Civil Procedure. One critical requirement (item 3 of Article 118) is that the content of the foreign judgment must not be contrary to the "public order or good morals" of Japan.

The Supreme Court clarified that while a foreign judgment based on a legal system or institution not adopted in Japan is not automatically contrary to public order, it will be deemed so if its recognition "conflicts with the fundamental principles or basic tenets of Japan's legal order."

Key Principle 2: Maternal Definition under Japanese Civil Code – "The Woman Who Gives Birth is the Mother"

The Supreme Court then delved into the principles of establishing parent-child relationships under Japanese law:

- It emphasized that parent-child relationships are among the most fundamental of personal status relations, forming the basis for many aspects of social life, deeply affecting public interest, and having a significant impact on the welfare of children.

- The criteria for recognizing such relationships must be clear and uniformly applied, as they pertain to the core of Japan's family law system.

- The Japanese Civil Code is understood to recognize parent-child relationships only in the circumstances it explicitly provides for or presupposes.

- Therefore, a foreign court judgment that recognizes a parent-child relationship in a manner not permitted by the Japanese Civil Code inherently conflicts with these fundamental principles and, as such, violates Japanese public order.

Specifically regarding maternity, the Court stated:

- While the Civil Code does not contain a direct, explicit provision defining the mother of a legitimate child, its structure (e.g., Article 772, paragraph 1, concerning the presumption of legitimacy of a child conceived during marriage) operates on the fundamental premise that the woman who conceives and gives birth to a child is that child's mother.

- This principle—that maternity is established by the act of giving birth—has also been consistently applied to non-marital children (citing a Supreme Court precedent from April 27, 1962).

- The Court acknowledged that these legal provisions were established at a time when it was a natural and virtually invariable fact that the woman who gave birth was also the child's genetic mother. The law recognized the objective and externally obvious fact of birth as the basis for establishing maternity, which also served the child's welfare by quickly and clearly defining the maternal relationship.

With the advent of ART, it is now possible for the woman who provides the egg (the genetic mother) to be different from the woman who gestates and gives birth (the gestational mother). The Court directly addressed whether, under the current Civil Code, a woman who provides an egg but does not give birth can be recognized as the legal mother. It concluded:

"Upon examining this point, the Civil Code contains no provisions that would suggest a woman who did not conceive and give birth to a child should be deemed that child's mother. The absence of provisions for such cases is due to such situations not being contemplated at the time of the Code's enactment. However, considering that parent-child relationships deeply concern public interest and child welfare and should be determined uniformly by clear standards, the interpretation of the current Civil Code compels the conclusion that the woman who gestates and gives birth to a child must be deemed that child's mother. A legal maternal relationship cannot be recognized with a woman who did not gestate and give birth to the child, even if she provided the egg."

Application to the Nevada Judgment and the Need for Legislation

Based on this interpretation, the Supreme Court found that the Nevada court judgment, by recognizing X2 (the genetic mother who did not give birth) as the legal mother of B and C, established a parent-child relationship inconsistent with the fundamental principles of Japanese family law. Consequently, the Nevada judgment was deemed contrary to Japanese public order and could not be granted legal effect in Japan.

Since the foreign judgment was not recognized, Japanese law (as the law of the parents' home country) would apply to determine the parentage of B and C. Under Japanese law, X2, not having given birth, could not be recognized as the mother. Therefore, the birth registration listing X1 and X2 as the parents of legitimate children could not be accepted as filed.

The Supreme Court explicitly stated that the issue of surrogacy, being a situation not contemplated by the current Civil Code, requires thorough legislative examination. This examination should cover medical, ethical, and social aspects, the potential problems for all parties involved (including the surrogate mother, the intending parents, and the child), the sincere desire of individuals to have genetically related children, and public sentiment. The Court strongly urged "prompt legislative action."

Supplementary Opinions: Highlighting the Path of Special Adoption

While the legal conclusion denied X2 direct maternal status based on the Nevada judgment, three of the Supreme Court justices provided important supplementary opinions. They concurred with the majority's legal reasoning but went further to address the welfare of the children, B and C. Significantly, these justices pointed out that "special adoption" (特別養子縁組 - tokubetsu yōshi engumi) offered a viable legal pathway for X1 and X2 to establish a secure legal parent-child relationship with B and C under Japanese law. They noted that considering factors like the lack of parental intent from the surrogate mother (A) and her husband, and X1 and X2's clear desire and actions to raise the children, the conditions for special adoption could likely be met.

The Aftermath and Legislative Response

This Supreme Court decision had significant repercussions and spurred further legal and societal discussion.

- Special Adoption Granted: Following the Supreme Court's ruling, in March 2008, X1 and X2 were reportedly successful in legally adopting B and C through the special adoption system in Japan. This provided the children with legal security within the Japanese framework, albeit through a different route than direct recognition of X2 as the birth mother.

The 2020 ART Act: Years later, in December 2020, Japan enacted the "Act on Special Provisions to the Civil Code Concerning Parent-Child Relationships with Regard to Assisted Reproductive Technology Provided by a Third Party and Other Related Matters" (often referred to as the ART Act). While this Act primarily focuses on issues related to third-party gamete donation, Article 9 of the Act is highly relevant to the principle discussed in the surrogacy case. It states:

"When a woman gives birth to a child conceived through assisted reproductive technology using an egg from another woman (including an embryo derived from such an egg), the woman who gave birth shall be that child's mother."

This provision effectively codifies the "birth mother is the legal mother" rule for all ART births involving donated eggs, regardless of whether a surrogacy arrangement is involved. This aligns directly with the Supreme Court's 2007 interpretation of the Civil Code.

It is important to note that the ART Act did not legalize or regulate the practice of surrogacy itself in Japan. The Act's supplementary provisions indicate that the broader issues surrounding ART, including surrogacy, are subjects for future governmental review and potential legislative action.

Challenges for International Surrogacy and "Child Welfare"

The Supreme Court's decision highlighted the legal precarity that can arise for children born through international surrogacy arrangements when their parentage, though legally established in the country of birth, is not recognized in their intended parents' home country. This creates a "limping relationship," where the child's legal status differs across jurisdictions.

While the strict application of domestic law (the "birth mother rule") was upheld, the supplementary opinions favoring special adoption signaled a pragmatic concern for the welfare of the children already born. Special adoption offers a means to achieve legal parentage and stability for the child within Japan, even if it doesn't recognize the commissioning mother's maternal status from birth based on genetics or a foreign surrogacy contract.

Conclusion

The Japanese Supreme Court's 2007 decision in this landmark surrogacy case decisively affirmed that, under the then-current interpretation of the Civil Code, legal motherhood is established by the act of giving birth, not solely by a genetic link. It also robustly defended the principle that foreign judgments fundamentally conflicting with Japan's core family law principles will not be recognized on grounds of public order.

While denying the direct registration of the commissioning mother as the legal mother based on the US judgment and surrogacy arrangement, the Court, through its justices' supplementary opinions, acknowledged the importance of the children's welfare and pointed towards special adoption as a viable domestic legal solution. The subsequent enactment of the 2020 ART Act, particularly Article 9, has further solidified the "birth mother rule" in Japanese law for ART births. The case continues to be a significant reference for the complex legal and ethical debates surrounding surrogacy and the ongoing efforts to adapt national laws to the realities of globalized assisted reproductive technologies.