Surrogacy Across Borders: Japanese Supreme Court on Recognizing Foreign Parentage Orders

Date of Decision: March 23, 2007

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

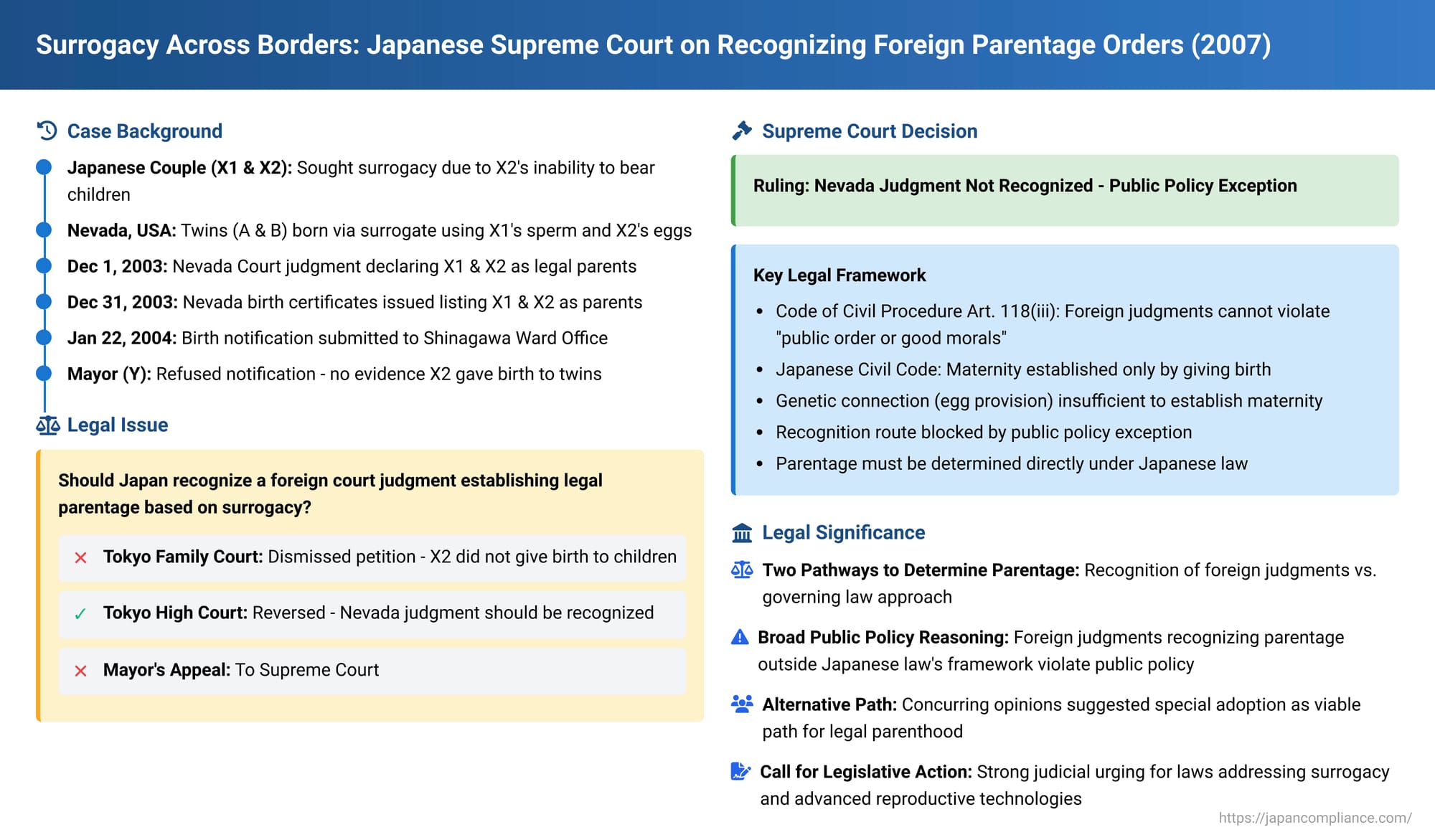

The rise of assisted reproductive technologies (ART), including international surrogacy arrangements, presents profound legal challenges globally. When a child is born through surrogacy in one country where it is legal and parentage is established there, the intended parents often face difficulties obtaining legal recognition in their home country if its laws differ. A pivotal Japanese Supreme Court decision on March 23, 2007, confronted this issue directly, ruling on the recognition of a U.S. court order that declared a Japanese couple the legal parents of twins born via a surrogate mother in Nevada using the couple's genetic material. The case highlights the significant role of domestic public policy in the recognition of foreign judgments concerning parent-child relationships.

The Factual Background: A Journey for Parenthood via International Surrogacy

The case involved a Japanese married couple, Mr. X1 and Ms. X2, who sought to have children:

- Due to Ms. X2 being unable to carry a pregnancy, the couple pursued surrogacy in Nevada, USA, a jurisdiction where such arrangements were legally permitted under specific conditions (primarily that the surrogate mother received no payment beyond medical and living expenses).

- The twins, A and B, were conceived using Mr. X1's sperm and Ms. X2's eggs, and were carried to term and delivered by a U.S. surrogate mother.

- On December 1, 2003, the Second Judicial District Court, Family Division, in Washoe County, Nevada, issued a judgment ("Nevada Judgment"). This judgment confirmed that Mr. X1 and Ms. X2, being the genetic parents, were the legal parents of A and B.

- Subsequently, on December 31, 2003, a Nevada birth certificate was issued listing Mr. X1 as the father and Ms. X2 as the mother of the twins.

- Upon returning to Japan with A and B, Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 submitted a birth notification (出生届 - shusshō todoke) to the Shinagawa Ward Office in Tokyo on January 22, 2004, seeking to register the twins as their legitimate children.

- The Ward Mayor (Y) refused to accept (不受理 - fujuri) this birth notification. The reason given was that there was no factual evidence that Ms. X2 (the intended mother) had actually given birth to A and B, which is the conventional basis for establishing maternity in Japan.

The Legal Path in Japan: From Family Court to Supreme Court

The couple challenged the Ward Mayor's refusal:

- The Tokyo Family Court dismissed their petition, upholding the Ward Mayor's decision on the grounds that Ms. X2 had not given birth to the children.

- On appeal, the Tokyo High Court reversed the Family Court's decision. The High Court ruled that the Nevada Judgment establishing Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 as the legal parents should be recognized in Japan under Article 118 of Japan's Code of Civil Procedure (which governs the recognition of foreign court judgments). Consequently, it ordered the Ward Mayor to accept the birth notification.

- The Ward Mayor then brought the case to the Supreme Court via a permitted appeal.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Nevada Judgment Not Recognized Due to Public Policy

The Supreme Court overturned the Tokyo High Court's decision, ultimately upholding the Ward Mayor's refusal to register Ms. X2 as the mother based on the Nevada Judgment. The Court's reasoning was rooted in the public policy exception to the recognition of foreign judgments:

1. Recognition of Foreign Judgments and Public Policy:

The Court began by outlining the conditions for recognizing a foreign judgment under Article 118 of the Code of Civil Procedure. A key condition (Article 118(iii)) is that the content of the foreign judgment must not be contrary to Japan's "public order or good morals" (公の秩序又は善良の風俗 - kō no chitsujo mata wa zenryō no fūzoku). A foreign judgment is considered contrary to public order if it is incompatible with the fundamental principles or basic ideals of Japan's legal system.

2. Parent-Child Relationships as a Fundamental Part of Japan's Legal Order:

The Supreme Court emphasized that the determination of how legal parent-child relationships are established forms a cornerstone of a nation's family law system. It stated that Japan's Civil Code, which defines the country's family law order, intends to recognize such relationships only in the specific circumstances it outlines, and not in others. Therefore, a foreign court judgment that recognizes a parent-child relationship between individuals in a manner not permitted by the Japanese Civil Code is deemed incompatible with the fundamental principles of Japan's legal order and, thus, contrary to public policy.

3. Japanese Law on Maternity: The Gestational Principle:

The Court then articulated its interpretation of maternity under the existing Japanese Civil Code:

- In light of the profound public interest in parent-child relationships, the welfare of the child, and the need for clear and uniform standards, the current interpretation of the Civil Code dictates that the woman who conceives and gives birth to a child is legally recognized as that child's mother.

- A maternal relationship cannot be legally established with a woman who did not conceive and give birth to the child, even if she provided the egg (i.e., is the genetic mother).

4. Conclusion on the Nevada Judgment:

The Nevada Judgment recognized Ms. X2 as the legal mother of A and B, despite her not having given birth to them. This, the Supreme Court found, establishes a parent-child relationship in a way that the Japanese Civil Code does not permit.

Consequently, the Nevada Judgment was deemed incompatible with the fundamental principles of Japan's current family law order and, therefore, contrary to Japanese public policy as stipulated in Article 118(iii) of the Code of Civil Procedure. As a result, the Nevada Judgment could not be recognized as having legal effect in Japan.

5. Consequence: Parentage Determined Under Japanese Law:

Since the Nevada Judgment was not recognized, the question of establishing a legitimate parent-child relationship between Mr. X1, Ms. X2, and the children A and B fell to be determined directly under Japanese law. As Japanese nationals, the governing law for their parent-child relationships under Japan's private international law rules (Article 28(1) of the Act on General Rules for Application of Laws) is Japanese law.

Under the Japanese Civil Code's interpretation (maternity determined by gestation and birth), Ms. X2 could not be recognized as the mother of A and B. Thus, a legitimate parent-child relationship for Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 as a married couple with A and B could not be established for the purpose of the birth registration as sought.

Two Routes to Determining Parentage in International Cases

The Supreme Court's decision implicitly acknowledged two potential pathways for determining parentage in cases with international elements:

- The Recognition Approach: If a foreign court has already rendered a judgment on parentage, Japanese courts will first consider whether to recognize that judgment under the criteria set out in Article 118 of the Code of Civil Procedure (or Article 79-2 of the Family Case Procedures Act for certain types of family judgments, following later amendments).

- The Governing Law Approach: If no foreign judgment exists, or if an existing foreign judgment is not recognized (as in this case), the parent-child relationship must then be determined by applying Japanese private international law rules (Articles 28 et seq. of the Act on General Rules for Application of Laws) to identify the applicable substantive law.

The Supreme Court's methodology in this case demonstrated that if the recognition route is barred (e.g., by public policy), the governing law approach is then employed.

Debate and Scope of the Supreme Court's Public Policy Reasoning

This decision sparked considerable academic discussion, particularly regarding the breadth of the Supreme Court's public policy reasoning:

- Focus on Systemic Differences: The Supreme Court emphasized the fundamental difference between how Japanese law establishes maternity (based on gestation and birth) and how the Nevada judgment did (based on genetic connection and parental intent in a surrogacy context). This was a departure from the High Court's approach, which had considered the specific "merits" of the surrogacy agreement and the couple's intentions to find no public policy violation.

- Scope of "Parent-Child Relationships Not Recognized by Japanese Law": The Court's statement that any foreign judgment recognizing parentage in a way the Japanese Civil Code does not is contrary to public policy appeared very broad. Commentators have suggested this should be interpreted carefully:

- It might be primarily limited to the context of surrogacy, given that Japan had (and still largely has) no specific legislation regulating or prohibiting surrogacy at the time, making it a particularly sensitive area.

- An overly broad interpretation could conflict with other Supreme Court precedents that have recognized foreign family law concepts not identical to Japanese ones (e.g., certain step-parent relationships under Korean law that have legal effects in Japan).

- The strength of the "domestic connection" to Japan in a particular case might also influence the public policy assessment; a case with weaker ties to Japan might see a foreign judgment more readily recognized.

- Evolving Nature of Public Policy: Public policy is not static. It can evolve with societal changes, scientific advancements, and legislative reforms. Future legislation in Japan specifically addressing assisted reproductive technologies and surrogacy could significantly alter the application of public policy in similar cases.

The Human Element and Alternative Paths (Concurring Opinions)

The Supreme Court's decision included concurring opinions from three justices. While agreeing with the legal outcome, they acknowledged the couple's strong desire to raise the children to whom they were genetically related and the genuine care they were providing. These opinions also pointed out that under the existing Japanese legal framework, special adoption might offer a viable pathway for Mr. X1 and Ms. X2 to establish a legal parent-child relationship with A and B. All opinions strongly urged for prompt legislative action in Japan to address the complex legal, ethical, and social issues raised by surrogacy and other advanced assisted reproductive technologies.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2007 decision in this international surrogacy case is a landmark ruling. It firmly established that, under the then-current interpretation of Japanese law, legal maternity is determined by gestation and birth, and a foreign court order establishing maternity on a different basis (such as genetic connection and intent in a surrogacy arrangement) would not be recognized in Japan if it conflicted with this fundamental principle of Japanese family law, due to the public policy exception. The case underscores the significant challenges faced by individuals using international surrogacy to build families when their home country's laws have not kept pace with evolving medical technologies and social practices. It also highlighted the pressing need for legislative reform in Japan to provide clarity and address the legal status of children born through such arrangements.