Suicide and Sanity: A 1916 Japanese Landmark Ruling on Life Insurance Exclusions

Date of Judgment: February 12, 1916

Case: Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation), Third Civil Affairs Department, Case No. 791 (o) of 1915 (Claim for Insurance Proceeds)

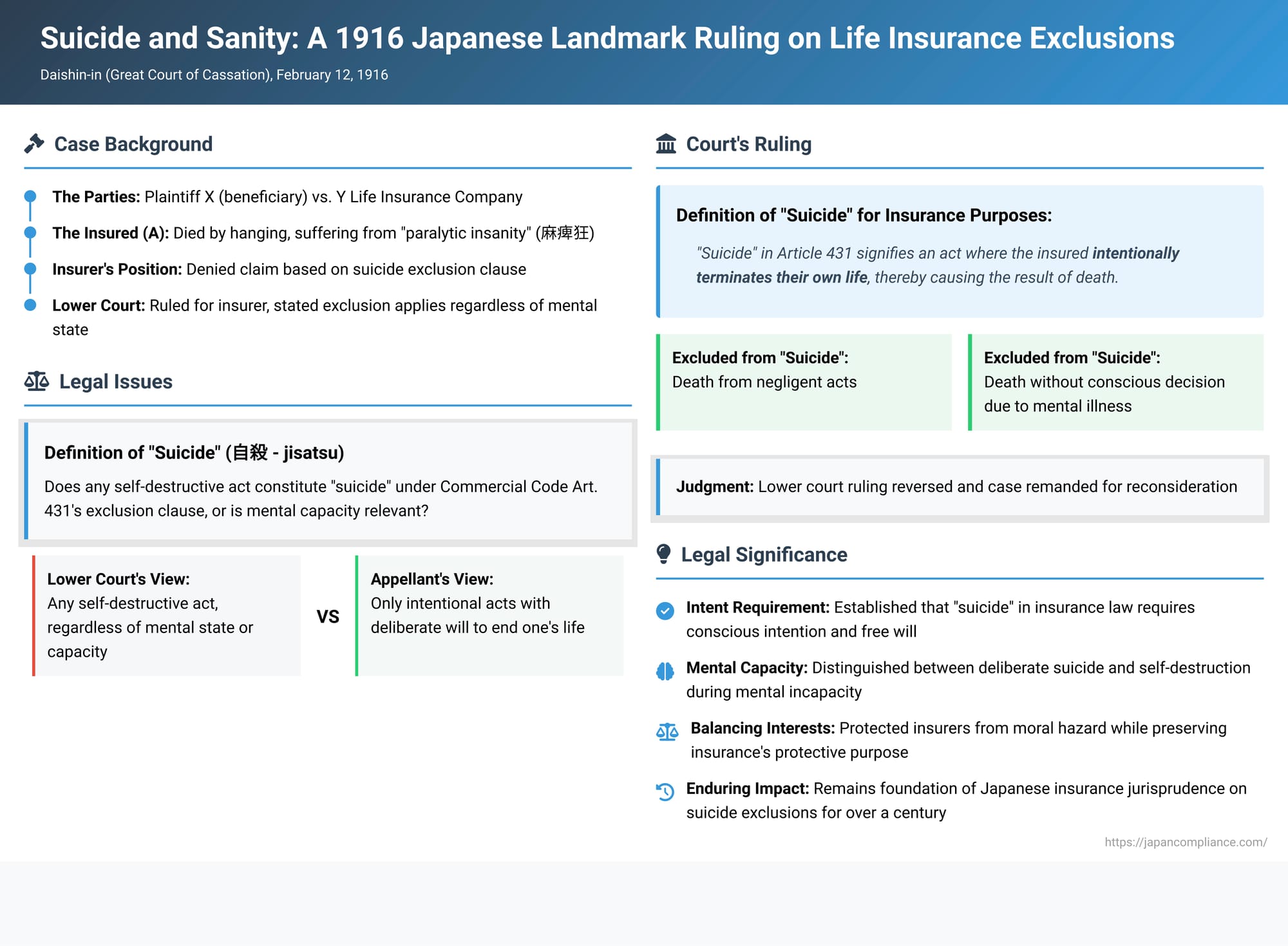

Life insurance policies often include clauses that exempt the insurer from paying benefits if the insured dies by suicide. However, the term "suicide" itself can be fraught with complexity, especially when the insured was suffering from a mental illness at the time of their death. Does any act of self-destruction fall under such an exclusion, or is the insured's mental state and capacity for free will a critical factor? This profound question was addressed in a foundational 1916 ruling by Japan's Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation), the highest court at the time, which continues to shape the understanding of suicide exclusion clauses in Japanese insurance law.

The Tragic Circumstances: Facts of the Case

The plaintiff, X, filed a claim for life insurance proceeds with Y Life Insurance Company following the death of the insured, A. A had died by hanging himself, an act attributed to a severe mental illness described as "paralytic insanity" (麻痺狂 - mahikyō). Y Life Insurance Company refused to pay the claim, presumably invoking a suicide exclusion clause.

The initial trial court, the Akita District Court, sided with the insurer. It reasoned that the relevant provision of the old Commercial Code (Article 431 at the time, later Article 680, and a precursor to Article 51 of the current Insurance Act) concerning suicide did not differentiate based on the cause of the suicide. Therefore, even if the insured took their own life due to a mental illness, the insurer was automatically exempted from liability. X, the claimant, appealed this decision to the Daishin-in.

The Legal Question: Defining "Suicide" for Insurance Purposes

The core of the appeal rested on the interpretation of "suicide" (自殺 - jisatsu) as used in Article 431 of the old Commercial Code. This article stipulated that an insurer was exempt from the obligation to pay insurance benefits if "the insured died due to suicide, dueling or other crimes, or execution of a death penalty".

X argued that this provision was established to ensure a fair distribution of risk and protection of interests between the contracting parties, considering the fundamental principles of the insurance system. Consequently, "suicide" in this legal context should exclusively refer to instances where the insured intentionally and with deliberate will takes their own life. X contended that it should not encompass situations where death results from the insured's own negligence or, crucially, from actions taken during a state of mental illness that lead to self-destruction without a conscious and free decision to end one's life.

X acknowledged that while other subsections of Article 431 (e.g., dealing with a beneficiary or policyholder intentionally causing the insured's death) explicitly used the term "intentionally" (故意ニテ - koi nite), the subsection on suicide did not. However, X argued that the absence of this specific adverb did not mean suicide could be unintentional. The very word "suicide," X asserted, inherently implies a deliberate and intentional act. Thus, the trial court, despite recognizing that A's death by hanging was due to his mental illness, erred in law by classifying it as "suicide" for the purpose of the exclusion.

The Daishin-in's Landmark Definition

The Daishin-in reversed the lower court's judgment and remanded the case for reconsideration. In doing so, it provided a seminal definition of "suicide" in the context of life insurance exclusions:

The Court ruled that "suicide," as referred to in Article 431, paragraph 1, item 1 of the Commercial Code, signifies an act where the insured intentionally terminates their own life, thereby causing the result of death.

Crucially, the Daishin-in clarified that this definition does not include situations where:

- The fatal outcome is a result of a negligent act by the insured.

- The death results from actions taken by the insured while in a state of mental derangement due to mental illness or other causes, where the insured has not formed a conscious decision to end their own life.

Therefore, the Court stated, if an insured person dies due to these latter causes—that is, without the requisite intent due to mental derangement—the insurer is, as a matter of course, not exempted from the obligation to pay the insurance benefits under the said article.

The Daishin-in noted that the lower court had found that A's death was by hanging due to "paralytic insanity". However, the Daishin-in found the lower court's judgment ambiguous. It was unclear whether the lower court believed A's act was still a "suicide" based on his own decision despite the mental illness, or if it had misinterpreted the law by deeming any self-inflicted death during mental illness as "suicide" for the purpose of the exclusion. This ambiguity or misapplication of legal principles necessitated the reversal.

Elaborating on "Intentional" Self-Destruction

This 1916 ruling established a vital principle: for a suicide exclusion clause to apply, the act of self-destruction must be the result of the insured's free and conscious will.

The Core Principle: Free and Conscious Decision-Making

The Daishin-in's decision placed paramount importance on the insured's capacity for "意思決定" (ishi kettei)—decision-making. "Suicide," in the legal sense relevant to insurance exclusions, is not merely the act of causing one's own death, but doing so with the deliberate intention to achieve that outcome.

Mental Incapacity as an Exception

Consequently, acts leading to death that occur while the insured is in a state of severe mental impairment, where free and rational decision-making is impossible, do not fall under the definition of "suicide" for exclusion purposes. This would include situations akin to shinshin sōshitsu (心神喪失), a state of being unable to discern right from wrong or to act according to such discernment, similar to legal insanity. If a mental illness vitiates the capacity for free will to such an extent, an act of self-destruction would not be considered an "intentional" suicide that triggers the exclusion clause. It's worth noting that German insurance contract law, for instance, explicitly excludes from the definition of suicide acts committed in a "pathological disturbance of mental activity" that prevents free decision-making.

However, merely suffering from a mental illness is not, in itself, sufficient to automatically negate a suicide exclusion. If the insured, despite a mental condition, still possessed the capacity to understand the nature of their actions and to form a conscious intent to end their life (perhaps during a lucid interval or if the illness was not severe enough to obliterate free will), the act could still be classified as suicide under the exclusion.

Burden of Proof

In such cases, the burden of proof is typically allocated in two stages. First, the insurer, seeking to rely on the suicide exclusion, bears the burden of proving that the insured's death was a result of suicide. If the insurer meets this burden, the onus then generally shifts to the claimant (e.g., the beneficiary or the deceased's estate) to prove that the suicide occurred while the insured was in a state of mental incapacity that rendered them unable to make a free and conscious decision to end their life. This latter proof is necessary to overcome the exclusion and establish the insurer's liability.

Factors Considered by Courts Today

Building on the principle established in 1916, modern Japanese courts, when assessing whether a suicide by a mentally ill insured falls under an exclusion clause, often consider a range of factors to determine the insured's mental state and capacity for free will at the time of the act. These typically include:

- The insured's personality and character before the onset of any mental illness.

- The insured's behavior, statements, and overall mental condition leading up to the suicide attempt.

- The manner and method of the suicide attempt (e.g., evidence of planning versus impulsivity).

- The possibility of other motives for the suicide besides the mental illness itself.

Legal scholars point out that while this framework is commonly used, it is not without its critiques. For example, pre-illness personality is an indirect indicator of mental state at the time of death; distinguishing between impulsive and planned suicides may not be straightforward when severe suicidal ideation is driven by mental illness; and other motives can often be intertwined with, or even causes of, the mental illness itself. These factors are generally viewed as elements for a comprehensive assessment rather than rigid, absolute requirements.

The Rationale Behind Suicide Exclusions (and its Limits)

The inclusion of suicide exclusion clauses in life insurance policies is generally justified on several grounds:

- Preventing Moral Hazard: Insurance contracts are aleatory (dependent on chance). Allowing coverage for intentional self-destruction could incentivize individuals to take out policies with the intent of suicide, which undermines the principle of good faith essential to insurance.

- Deterring Misuse of Insurance: Such clauses aim to prevent life insurance from being used for improper purposes, such as securing a financial windfall for others through a planned suicide.

- Social Considerations: Historically, there has been a societal concern that providing insurance benefits for suicide might be seen as condoning or even encouraging such acts.

However, the Daishin-in's interpretation implicitly recognizes the limits of these rationales. Suicide itself is not classified as a criminal act in Japan. Furthermore, a primary purpose of life insurance is often the financial protection of the insured's surviving family members. Therefore, a rigid, all-encompassing exclusion for any act of self-destruction, regardless of mental state, might run counter to this protective aim.

Reflecting this balance, current Japanese insurance law (Insurance Act Article 51) treats the suicide exclusion as an optional, rather than a mandatory, provision. In practice, most life insurance policies today do not enforce a blanket exclusion for suicide throughout the life of the policy. Instead, it is common for policies to stipulate that suicide will be excluded only if it occurs within a specified period from the policy's inception, typically two or three years. After this period, suicides are generally covered, regardless of the insured's mental state at the time, though different rules might apply to claims for severe disability benefits arising from an intentional act.

Distinction from Workers' Compensation Standards

It's interesting to note a distinction in how suicide is treated in the context of Japanese workers' compensation insurance (Rosai Hoken). In Rosai cases, if a worker commits suicide due to a recognized work-related mental disorder (e.g., those classified under ICD-10 categories F0-F4), there is a presumption that the mental disorder severely impaired their normal judgment and ability to make rational decisions, or significantly inhibited their mental capacity to refrain from suicide. In such circumstances, the suicide is generally not considered an "intentional" act that would disqualify the claim for Rosai benefits.

However, Japanese courts have generally been reluctant to automatically apply this more lenient Rosai presumption to life insurance suicide exclusion cases. They often cite the different purposes and underlying principles of the two systems. This divergence in approach means that a suicide acknowledged as resulting from a work-induced mental disorder for workers' compensation purposes might still be subject to a suicide exclusion under a private life insurance policy if the criteria for lacking free will (as per the Daishin-in's standard) are not met. This remains an area of some legal contention.

Significance and Legacy of the 1916 Ruling

The Daishin-in's 1916 decision was a landmark judgment that profoundly influenced Japanese insurance law.

- It established the foundational legal definition of "suicide" for the purpose of insurance exclusion clauses, critically linking it to the insured's intent and capacity for free and conscious decision-making.

- This ruling drew a crucial distinction between a deliberate, voluntary act of suicide and acts of self-destruction committed while in a state of severe mental incapacity where free will is absent.

- It continues to underpin how courts approach suicide exclusion clauses today, particularly when the mental state of the insured at the time of death is in question.

Concluding Thoughts

More than a century later, the Daishin-in's 1916 ruling on suicide and sanity remains a cornerstone of Japanese insurance jurisprudence. By recognizing that not all acts of self-destruction are the product of a free and conscious will, the Court set a humane and reasoned boundary for the application of suicide exclusion clauses. This principle ensures that while insurers are protected from certain types of moral hazard, the fundamental protective purpose of life insurance is not unduly undermined in tragic cases where an insured's mental illness leads to their death without a truly voluntary act of self-destruction. The decision reflects a careful balancing of contractual interests, ethical considerations, and the compassionate understanding of human frailty.