Suicide After the Waiting Period: Japanese Supreme Court on Life Insurance Payouts and 'Insurance Purpose' Suicides

Date of Judgment: March 25, 2004

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Case No. 734 (o) of 2001 & No. 723 (ju) of 2001 (Claim for insurance proceeds, main action for confirmation of non-existence of debt, and counterclaim thereto)

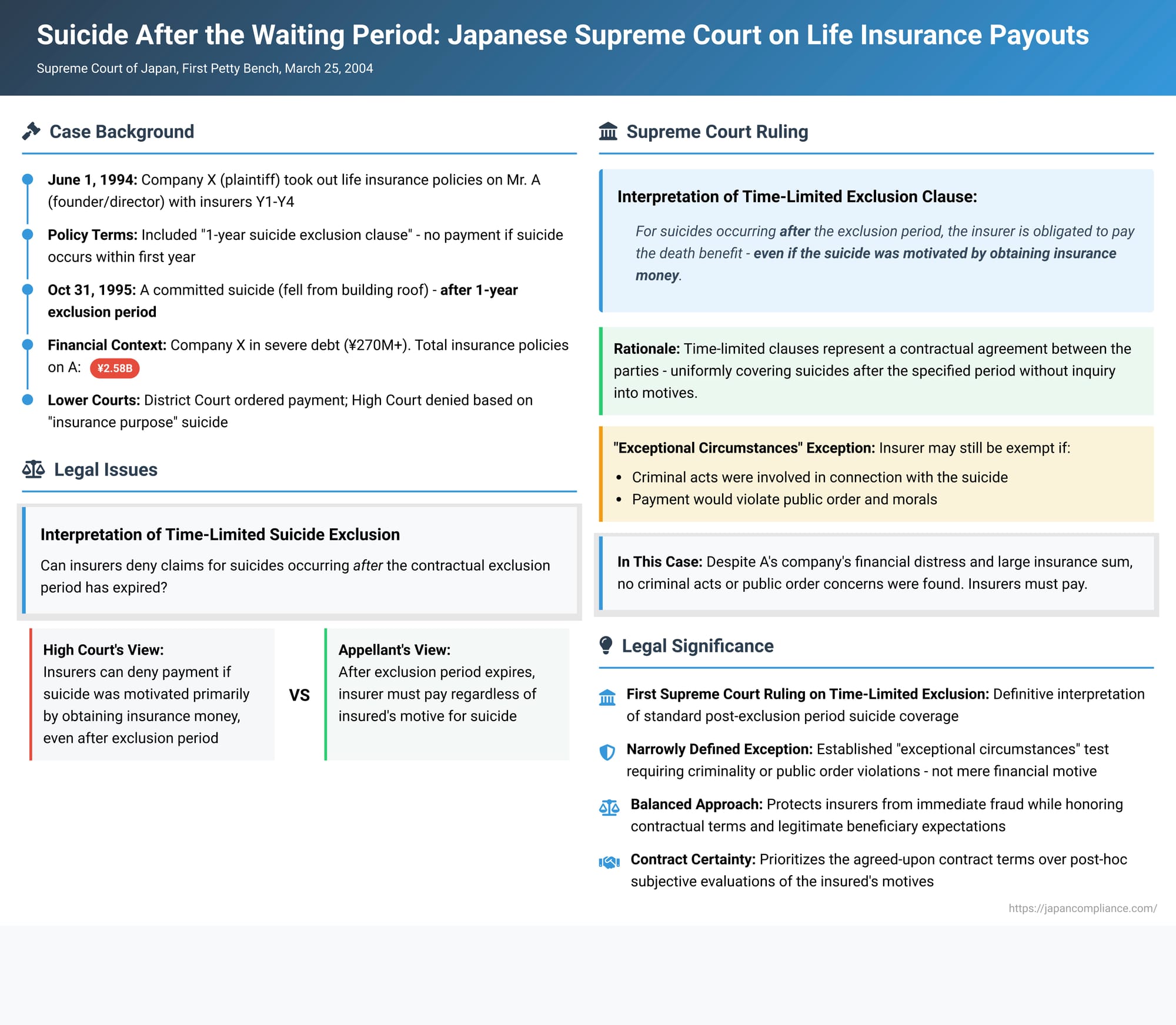

Life insurance policies commonly include a "suicide exclusion clause," which typically stipulates that the insurer will not pay death benefits if the insured commits suicide within a specified period (often one to three years) from the policy's inception. This period is designed to deter individuals from taking out insurance with the immediate intent of committing suicide for the payout. But what happens if the insured commits suicide after this contractually defined exclusion period has expired? Can the insurer still deny payment if it believes the suicide was primarily motivated by the desire for the insurance money to benefit others? This complex and sensitive issue was addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a landmark decision on March 25, 2004.

The High-Stakes Scenario: Facts of the Case

The case involved a company, X (the plaintiff and appellant), which was primarily engaged in waterproofing construction. Mr. A was the founder and representative director of X. By the end of fiscal year 1994, company X was in severe financial distress, with its total borrowings exceeding 270 million yen.

On June 1, 1994, X, acting as the policyholder and beneficiary, entered into several life insurance contracts ("1994 Contracts") with four insurance companies, Y1, Y2, Y3, and Y4 (the defendants and respondents). Mr. A was the insured under these policies. The terms and conditions applicable to these 1994 Contracts included a "1-year suicide exclusion clause" (一年内自殺免責特約 - ichinen-nai jisatsu menseki tokuyaku). This clause specified that the insurer would not pay the death benefit if the insured (A) committed suicide within one year from the date the insurer's liability commenced.

Mr. A died on October 31, 1995. His death occurred when he fell from the rooftop of a multi-unit residential building where his company, X, was undertaking rooftop waterproofing repair work. This date was more than one year after the 1994 Contracts had come into effect. The total sum of death benefits from all life insurance policies taken out on A's life (including the 1994 Contracts and others) amounted to a staggering 2.585 billion yen. As of September 1995, the combined monthly premium payments for these policies exceeded 2.25 million yen.

The Tokyo District Court, in the first instance, found that A's death was a suicide. However, it ruled in favor of company X regarding the main death benefit claims under the 1994 Contracts, effectively holding that a suicide occurring after the one-year exclusion period was covered.

The Tokyo High Court, on appeal, took a different view. It held that even if an insured person commits suicide after the contractual one-year exclusion period has passed, the insurer could still be exempt from the payment obligation if the insurer could prove that the suicide was committed solely or primarily for the purpose of obtaining the insurance money. The High Court reasoned that, in such cases, the general statutory provision regarding suicide exclusion (Article 680, paragraph 1, item 1 of the old Commercial Code) would still apply, notwithstanding the expiry of the specific one-year clause. Finding that A's suicide was indeed primarily for the purpose of securing the insurance payout, the High Court overturned the District Court's decision and rejected X's claim for the death benefits under the 1994 Contracts. Company X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Tug-of-War: Policy Clause vs. Alleged Insurance Fraud

The legal backdrop to this dispute was Article 680, paragraph 1, item 1 of the old Commercial Code (now Article 51, item 1 of the Insurance Act). This statutory provision generally listed the insured's suicide as a ground for the insurer's exemption from liability to pay insurance benefits. However, this statutory provision is not considered a mandatory rule of public order that parties cannot contractually modify.

Life insurance policies, as in this case, commonly include clauses that limit this suicide exclusion to a specific period (e.g., one year, though two or three years are common in current policies ). The crucial question was: what is the legal effect of such a time-limited exclusion clause once the specified period has passed? Does it mean that any suicide thereafter is covered, regardless of motive? Or can an insurer still invoke the spirit of the general statutory exclusion if it believes the suicide was a calculated act to trigger the policy payout? The High Court had leaned towards the latter, allowing for a broader inquiry into the motive behind a suicide even after the contractual exclusion period.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Interpretation

The Supreme Court partially set aside the High Court's judgment, particularly concerning the 1994 Contracts, and provided a definitive interpretation of the 1-year suicide exclusion clause.

Meaning of the Time-Limited Exclusion Clause:

The Court began by explaining the rationale behind the general statutory suicide exclusion in the Commercial Code. This exclusion is based on the understanding that an insured causing their own death by suicide intentionally brings about the insured event, which contravenes the principle of good faith and fair dealing required in life insurance contracts. Furthermore, if insurance benefits were paid in such cases, it could create the potential for life insurance to be exploited for improper purposes, and the exclusion aims to prevent this.

The Supreme Court then addressed the common practice of including time-limited suicide exclusion clauses (like the 1-year clause in this case) in policy terms. It reasoned that such clauses are formulated based on several considerations:

- If the motive for entering into a life insurance contract was the insured's intent to commit suicide for the insurance money, it is generally difficult to sustain such a motive over an extended period.

- For suicides occurring after a certain period has elapsed from the contract's inception, the connection to any initial motive at the time of contracting is usually tenuous.

- It is extremely challenging to definitively ascertain the true motive or cause of a suicide after the fact.

- Therefore, these time-limited clauses are designed to uniformly exempt the insurer from liability only for suicides occurring within the specified period, regardless of the specific motive (such as obtaining insurance money). This is considered an effective way to prevent the improper use of life insurance.

Based on this understanding, the Supreme Court interpreted the 1-year suicide exclusion clause as follows:

- For suicides occurring within one year of the policy's commencement, the clause provides for a uniform exemption of the insurer, without inquiry into the motive or purpose of the suicide, thereby preventing the misuse of the life insurance contract.

- Conversely, for suicides occurring after the one-year period has passed, the clause should be understood as an agreement that the insurer is not exempt from payment and will pay the death benefit. This holds true even if it is found that the motive or purpose of the suicide was the acquisition of the insurance money.

The "Exceptional Circumstances" Escape Hatch:

However, the Supreme Court introduced a critical caveat to this general rule for post-exclusion period suicides. It stated that the insurer could still be exempt from payment if "exceptional circumstances" (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō) exist. Such circumstances would include situations where:

- Criminal acts are involved in connection with the suicide.

- Permitting the payment of the death benefit for such a suicide would violate public order and morals.

The Court held that such a contractual agreement, which limits the scope of the statutory suicide exclusion to deaths occurring within a specified period, is valid and enforceable between the parties, notwithstanding the broader terms of the Commercial Code's statutory exclusion.

Application to A's Suicide (Regarding the 1994 Contracts):

Applying this interpretation to the facts of the case concerning the 1994 Contracts:

- Mr. A committed suicide after the one-year exclusion period from the commencement of these contracts had expired.

- Therefore, according to the 1-year suicide exclusion clause, the general statutory exclusion under the Commercial Code was rendered inapplicable, and the insurers were obligated to pay the death benefits, unless the aforementioned "exceptional circumstances" were present.

- The Court acknowledged that at the time of A's death, his company X was in a considerably dire financial situation, and both X and A had entered into numerous life insurance contracts with various insurers for very large sums. However, there was no evidence suggesting that any criminal acts were involved in the process leading to A's suicide, nor were there any other circumstances indicating that payment of the insurance benefits would be contrary to public order or morals.

- Consequently, the Supreme Court concluded that even if A's primary motive for suicide was to enable the beneficiary, company X, to obtain the insurance money, this did not constitute "exceptional circumstances" that would justify exempting the insurers from payment.

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its legal interpretation. The part of the judgment concerning the 1994 Contracts was therefore set aside and remanded to the Tokyo High Court for further proceedings consistent with the Supreme Court's interpretation. (The judgment also dealt with other policies and procedural aspects, leading to some parts being decided by the Supreme Court itself or dismissed).

Unpacking the "Exceptional Circumstances" Standard

The "exceptional circumstances" standard articulated by the Supreme Court is pivotal. While the Court found no such circumstances in this particular case, the standard itself echoes criteria seen in some prior lower court decisions that had denied insurance claims even for suicides occurring after the exclusion period. Those earlier cases often involved particularly egregious facts, such as murder-suicides, suicides coerced by third parties, or contract killings disguised as suicides. The Supreme Court's formulation, therefore, while providing a pathway for insurer exemption in extreme cases, sets a high bar. The mere motive of securing insurance funds for beneficiaries, in the absence of accompanying criminality or significant public order concerns, is generally insufficient to trigger this exception.

Why the Time Limit Matters

The Supreme Court's reasoning gives significant weight to the contractual agreement embodied in the time-limited suicide exclusion clause. It recognizes the practical difficulties insurers face in proving the subjective intent behind a suicide long after a policy has been in force. The clause, therefore, acts as a pragmatic solution: a strict exclusion for a limited initial period, followed by a general presumption of coverage thereafter. This approach acknowledges that while the intent to defraud an insurer through suicide might exist at the inception of a policy, it is less likely to be the sustained, primary driver of a suicide that occurs much later. The clause effectively represents a bargained-for allocation of risk between the insurer and the insured.

Significance of the Ruling

The Supreme Court's March 25, 2004, decision is a landmark in Japanese insurance law for several reasons:

- It was the first time the Supreme Court provided a definitive interpretation of standard time-limited suicide exclusion clauses with respect to suicides occurring after the specified exclusion period had ended.

- It establishes that, as a general rule, if a suicide occurs after the contractual exclusion period, the insurer is obligated to pay the death benefit, even if the suicide was motivated by a desire to secure the insurance payout for beneficiaries.

- It carves out a narrow set of "exceptional circumstances"—primarily involving criminality or violations of public order and morals—under which an insurer might still be exempt from payment for a post-exclusion period suicide. This provides a safety valve for truly egregious cases.

- The ruling brings a greater degree of certainty to policyholders and beneficiaries regarding coverage for suicides that happen after the initial exclusion window, reinforcing the idea that the primary purpose of such clauses is to deter immediate fraudulent intent rather than to scrutinize motives indefinitely.

Concluding Thoughts

The 2004 Supreme Court decision offers a carefully calibrated balance between the need to protect insurance companies from fraudulent claims and the legitimate expectations of policyholders and their beneficiaries. By generally upholding the contractual terms of time-limited suicide exclusion clauses, the Court affirmed that after the specified period, the insurer's obligation to pay is the norm. However, by also defining a narrow category of "exceptional circumstances," it left a pathway for insurers to deny claims in situations where payment would be clearly contrary to fundamental societal values. The precise contours of what constitutes "exceptional circumstances" will undoubtedly continue to be developed and refined through future case law, but this judgment provides a foundational framework for such analyses.