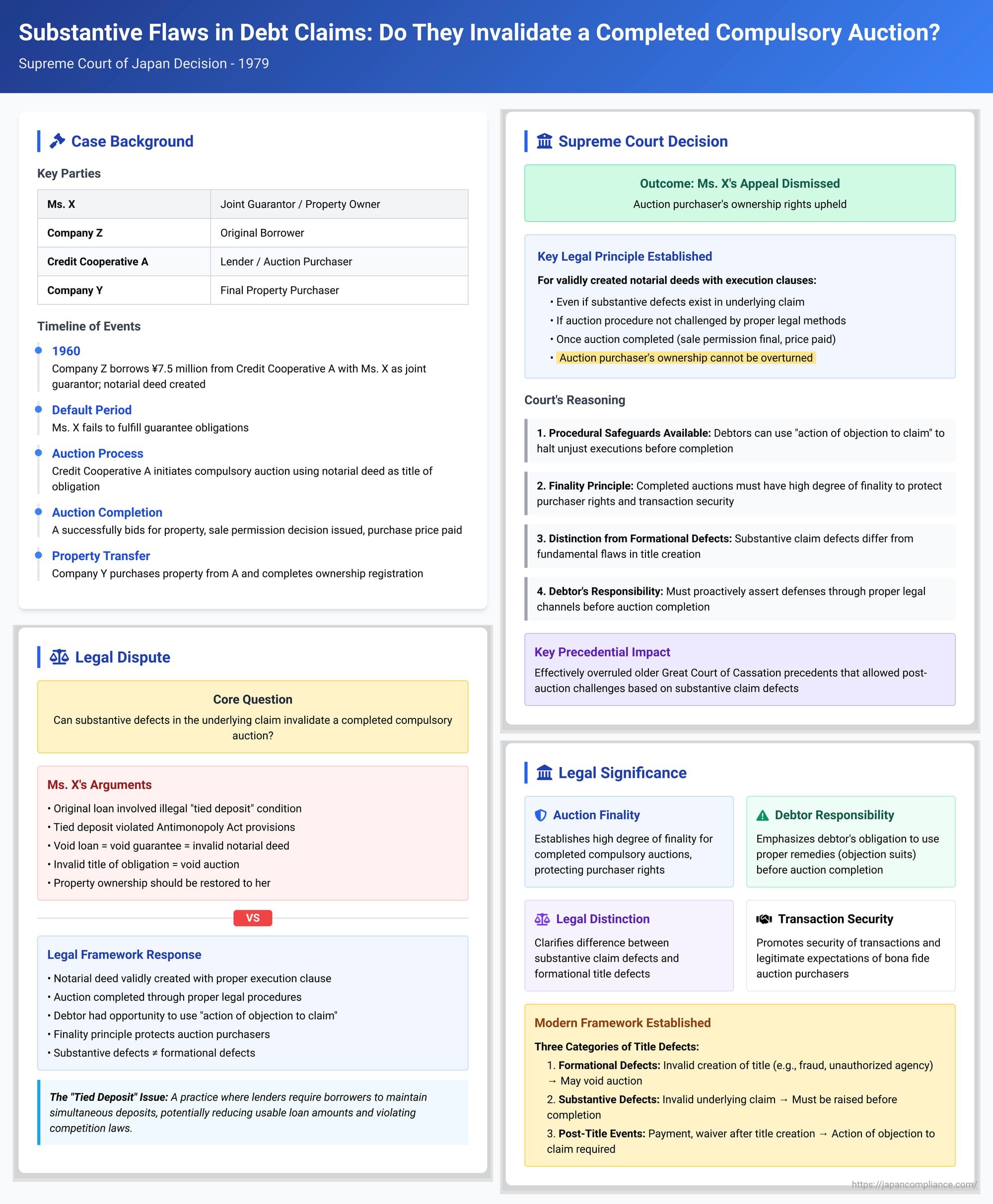

Substantive Flaws in Debt Claims: Do They Invalidate a Completed Compulsory Auction in Japan?

In Japan, initiating a compulsory execution, such as a real estate auction, requires a valid "title of obligation" (債務名義 - saimu meigi). This is typically a final court judgment, but can also be a notarial deed that includes an "execution undertaking clause" (執行受諾文言 - shikkō judaku mongon), where the debtor acknowledges they will submit to immediate execution if they default on the obligations stated in the deed. A critical question arises if the underlying claim documented in such a title of obligation is later found to have a substantive defect—for instance, if the contract forming the basis of the debt is void. Does this inherent flaw in the claim automatically nullify a compulsory auction that has already been completed based on that title, thereby undoing the ownership rights acquired by the auction purchaser? A 1979 Supreme Court of Japan decision provided a significant clarification on this issue, particularly in the context of notarial deeds used as titles of obligation.

Background of the Dispute

The case involved Ms. X (the plaintiff/appellant), who had acted as a joint guarantor for a loan of 7.5 million yen taken out by Company Z (Ms. X's auxiliary intervener in the lawsuit) from Credit Cooperative A in 1960. A notarial deed documenting this loan and Ms. X's guarantee was created among all three parties (A, Z, and X).

Ms. X subsequently failed to fulfill her guarantee obligations. As a result, Credit Cooperative A initiated compulsory auction proceedings against real property owned by Ms. X (the "Property"), using the notarial deed as its title of obligation. In the ensuing auction, Credit Cooperative A itself successfully bid for and purchased the Property. A formal "sale permission decision" (競落許可決定 - keiraku kyoka kettei, under the old law, now termed 売却許可決定 - baikyaku kyoka kettei or sale permission order) was issued, Credit Cooperative A paid the purchase price to the court, and the ownership of the Property was registered in A's name. Subsequently, Company Y (the defendant/respondent in the Supreme Court case) purchased the Property from Credit Cooperative A and also completed its ownership registration.

Ms. X then filed a lawsuit against Company Y. Her primary argument was that the original loan agreement between Credit Cooperative A and Company Z was, in fact, void. She contended that the loan was conditioned on an illegal "tied deposit" (拘束された即時両建預金 - kōsoku sareta sokuji ryōdate yokin)—a practice where a lender requires the borrower to simultaneously maintain a deposit with the lender, effectively reducing the usable loan amount and potentially violating public policy or antimonopoly laws. Ms. X argued that because the underlying loan to Z was void, her guarantee obligation for that loan was also non-existent. Consequently, the notarial deed, which documented this supposedly non-existent guarantee obligation, was an invalid title of obligation. Therefore, she claimed, the compulsory auction conducted based on this flawed title was void, and she had not legally lost her ownership of the Property. Ms. X sought a court order effectively canceling Y's registration and re-registering the property in her name, along with the surrender of the property.

It's noteworthy that the validity of the loan agreement between Credit Cooperative A and Company Z due to the tied deposit condition was also the subject of separate litigation between A and Z. While Ms. X's case against Y was pending before the Supreme Court, a different Supreme Court judgment (issued on June 20, 1977, concerning the A-Z contract) had held that such tied deposit conditions, while potentially violating Article 19 of Japan's Antimonopoly Act (Act on Prohibition of Private Monopolization and Maintenance of Fair Trade), do not automatically render the private law contract itself void. However, such a contract could be deemed void if found to be contrary to public order and good morals.

Ms. X's lawsuit against Y was dismissed by the court of first instance, and this dismissal was upheld by the appellate court. Ms. X then appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that the lower courts' decisions contradicted precedents set by the pre-WWII Great Court of Cassation.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court of Japan dismissed Ms. X's appeal, thereby upholding the lower court decisions against her. The Court laid down a clear principle regarding the effect of substantive defects in a claim underlying a notarial deed used for compulsory execution:

The Court stated that in a compulsory auction procedure based on a notarial deed that was created pursuant to a valid commissioning by the debtor (or their agent) and contains a valid execution undertaking clause by the debtor:

- Even if there exists a substantive reason that would render the rights and obligations stated in the notarial deed void (e.g., the underlying claim it represents is invalid or non-existent);

- If the auction procedure is not deemed impermissible by means of an "action of objection to claim" (請求異議の訴え - seikyū igi no uttae) or other legally prescribed methods before the auction procedure is completed (i.e., before the sale permission decision becomes final and the auction purchase price is paid);

- Then, once the auction is completed, the effect of the auction purchaser acquiring ownership of the auctioned property can no longer be overturned based on such substantive invalidity of the underlying claim.

Applying this principle to Ms. X's case, the Supreme Court noted that:

- The compulsory auction of Ms. X's Property, based on the notarial deed, had been completed: the sale permission decision in favor of Credit Cooperative A had become final, and A had paid the purchase price.

- Therefore, Ms. X's argument that the underlying loan to Company Z (and consequently her guarantee) was substantively void due to the tied deposit condition could not now negate the ownership acquired by Credit Cooperative A (and subsequently by Company Y).

- The Court also briefly referenced its 1977 ruling on the A-Z loan, reiterating that the tied deposit arrangement did not, in itself, automatically invalidate the loan contract under private law.

- The Great Court of Cassation precedents that Ms. X had relied upon were deemed to involve different factual circumstances and were not applicable to her case.

Significance and Analysis of the Decision

This 1979 Supreme Court judgment is a significant ruling that clarified the high degree of finality attached to completed compulsory auctions in Japan, even when the title of obligation (particularly a notarial deed) is based on an underlying claim that may have substantive defects.

- The Nature of Ownership Transfer in Compulsory Auctions: The PDF commentary explains that the transfer of ownership through a compulsory auction is generally understood to be founded upon the existence of an enforceable title of obligation. Article 79 of the Civil Execution Act states that the purchaser acquires the real property at the time they pay the purchase price. This provision, while specifying the timing of acquisition, presupposes that the auction was conducted based on a valid writ of execution issued for an enforceable title of obligation. The transfer effect is often conceptualized as a form of "sale" carried out under statutory procedures. For this "sale" to be effective, the authority to sell—vested in the creditor or the execution organ—is not seen as deriving from the actual, verified existence of the underlying debt, but rather from the existence of a formally valid and enforceable title of obligation (like the notarial deed here) that publicly certifies the claim. As long as the execution process itself is conducted lawfully based on such a title and is completed, the transfer of ownership to the purchaser is generally upheld.

- The Crucial Role of Debtor's Remedies (Specifically, the Action of Objection to Claim): The Supreme Court's reasoning heavily emphasizes the phrase: "unless the procedure is deemed impermissible by means of an action of objection to claim or other statutory methods." This highlights the procedural obligation on the debtor. If a debtor, like Ms. X, believes that the underlying claim documented in the title of obligation is non-existent, extinguished (e.g., by payment), or otherwise invalid, they must proactively use the remedies provided by the Civil Execution Act. The primary remedy in such situations is the "action of objection to claim" (請求異議の訴え - seikyū igi no uttae), provided for in Article 35. Through this lawsuit, the debtor can seek a court judgment declaring that the title of obligation is unenforceable due to such substantive defects. This judgment, if obtained, must then be presented to the execution court to stop or cancel the ongoing execution procedure before the auction is completed and the purchaser pays the price. The Japanese legal system is structured to protect the stability of auction sales and the legitimate expectations of bona fide purchasers. If a debtor has the opportunity to halt an unjust execution through such prescribed legal channels but fails to do so in a timely manner, they generally cannot later challenge the auction purchaser's acquired title based on those same substantive defects in the original claim.

- Distinction from Defects in the Formation or Validity of the Title of Obligation Itself: It is critical to distinguish the situation in this case—a substantive defect in the underlying claim represented by the title of obligation—from cases involving serious defects in the formation or inherent validity of the title of obligation itself. The PDF commentary points out that the Supreme Court has, in other precedents, invalidated auction sales and denied the purchaser's acquisition of title when the title of obligation was found to be essentially "non-existent" or void in relation to the debtor due to grave procedural flaws in its creation. Examples of such formational defects include:

- A title of obligation obtained by fraud where the debtor's address was falsified, and the debtor was kept entirely ignorant of the proceedings (Supreme Court, Feb. 27, 1968 – discussed in a previous blog post in this series).

- Notarial deeds created based on a commission by a person who lacked the authority to represent the debtor (e.g., an unauthorized agent) (Supreme Court, Apr. 3, 1973, and July 25, 1975).

In these kinds of scenarios, where the defect goes to the very legitimacy of the title of obligation as an instrument binding the debtor, the execution may be deemed as having been carried out "without a title of obligation." The current Supreme Court decision (1979) implicitly acknowledges this distinction by prefacing its core reasoning with the condition that the notarial deed in question was "created based on a valid commissioning by the debtor or their agent and an execution undertaking clause." The defect alleged by Ms. X concerned the substantive validity of the guaranteed loan, not a fundamental flaw in the procedure by which she, as guarantor, agreed to the execution undertaking in the notarial deed itself. The commentary concludes that there is now broad agreement that a mere substantive defect in the underlying claim (such as its non-existence or invalidity) does not rise to the level of a formational defect that would render the execution as one "without a title of obligation".

- Effective Overruling of Earlier Great Court of Cassation Precedents: The PDF commentary explains that a key reason this 1979 Supreme Court decision was considered significant enough for inclusion in the official reports (Minshū) was that it effectively changed the direction from older precedents of the Great Court of Cassation (Japan's pre-WWII Supreme Court). Some of these older precedents had suggested that if the right being enforced through an execution based on a notarial deed was "substantively invalid," the original owner could challenge the auction purchaser's title even after the auction was completed (e.g., Great Court of Cassation, Mar. 13, 1912). Another old ruling had denied the transfer of ownership where the underlying debt had been extinguished by payment prior to execution (Great Court of Cassation, July 17, 1936). This was often contrasted with the stricter approach taken when the title of obligation was a final court judgment, where even prior extinguishment of the debt generally did not undo an auction purchaser's acquired title (e.g., Great Court of Cassation, Apr. 6, 1938). The differing treatment was sometimes attributed to the perceived lesser degree of finality or procedural scrutiny involved in creating notarial deeds compared to court judgments. The 1979 Supreme Court decision, by applying a consistent rule protecting the auction purchaser from challenges based on substantive defects in the underlying claim (regardless of whether the defect was non-existence from the start or subsequent extinguishment), and by not differentiating between notarial deeds and other titles of obligation in this regard, effectively brought the treatment of notarial deeds into line with modern execution principles. It underscored the debtor's responsibility to proactively use the "action of objection to claim" to raise such substantive issues before the completion of the execution process.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1979 decision delivers a clear message regarding the finality of completed compulsory auctions in Japan. Substantive defects in the claim that underlies a formally valid title of obligation, such as a notarial deed with an execution clause, will generally not suffice to invalidate the ownership rights acquired by a purchaser at auction if the debtor failed to utilize statutory remedies like the "action of objection to claim" to halt the execution process before its completion. This ruling emphasizes the importance of timely action by debtors to assert their substantive defenses and reinforces the legal framework designed to protect the security of transactions arising from judicial auctions. It also distinguishes such substantive claim defects from more fundamental flaws in the creation or validity of the title of obligation itself, which, in certain egregious cases, can indeed lead to the nullification of an auction.