Substance Over Form: Japan's Supreme Court Scrutinizes a Movie Tax Shelter

Judgment Date: January 24, 2006

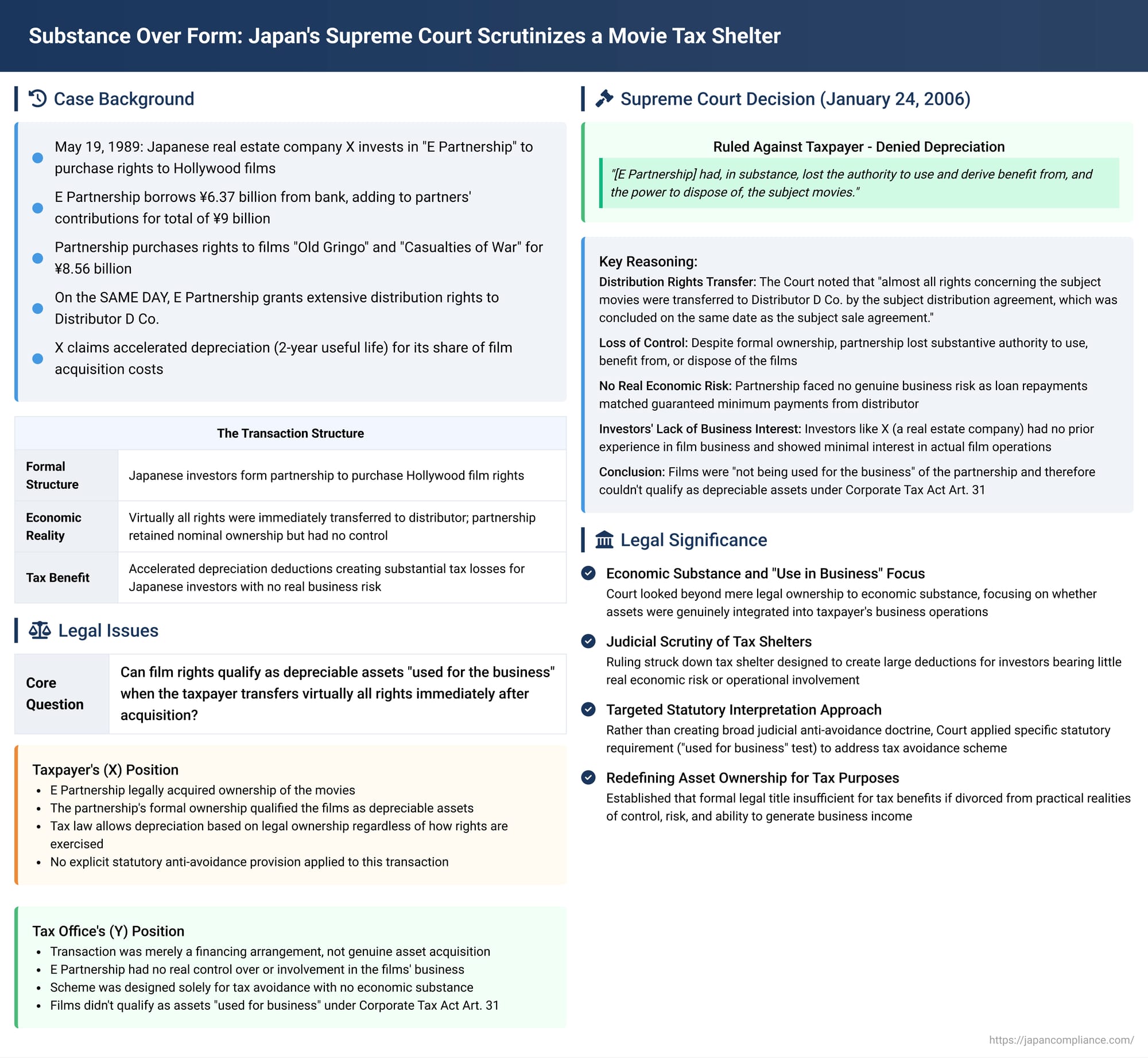

In a significant decision impacting the landscape of tax shelters in Japan, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court delivered a judgment in what is often referred to as the "Palazzina Case" (though this specific name is not used in the judgment itself, it's known by this moniker in some commentaries due to the plaintiff's name). The case involved a complex international transaction designed to generate substantial depreciation deductions for Japanese investors through investments in Hollywood movie rights. The Supreme Court, looking through the intricate legal structuring to the economic realities, upheld the tax authorities' denial of these deductions, focusing on whether the movie rights were genuinely "used in the business" of the investors' partnership.

The Allure of Hollywood: A Tax-Advantaged Investment Structure

The plaintiff, X, a Japanese real estate company, was approached by "ML Solicit Co." (an investment firm) with a proposal to participate in an investment scheme involving two Hollywood films: "Old Gringo" and "Casualties of War" (hereinafter "the subject movies"). X agreed and became a partner in "E Partnership," a partnership formed under the Japanese Civil Code, holding a 1/19th share.

The transaction, primarily executed on May 19, 1989, was structured as follows:

- Formation and Funding of E Partnership: Japanese investors, including X, formed E Partnership. X contributed approximately 137.95 million yen. E Partnership also secured a significant loan of over 6.37 billion yen from "Lender E Bank." The combined funds (partner contributions and the loan) totaled nearly 9 billion yen.

- Purported Purchase of Movie Rights: Using these funds, E Partnership purportedly purchased the subject movies from "Intermediary Seller C Co." for approximately 8.56 billion yen. The remaining funds were used for fees to ML Solicit Co. and Lender E Bank. Intermediary Seller C Co. had, in turn, acquired the movies from the original producer, "Producer F Co." (a major Hollywood studio). Producer F Co. received the sale proceeds via Intermediary Seller C Co.

- Immediate Grant of Distribution Rights: Crucially, on the same day as the purported purchase, E Partnership entered into a distribution agreement ("the subject distribution agreement") with "Distributor D Co.," a Dutch private limited company. This agreement granted Distributor D Co. extensive, virtually exclusive, and long-term rights to distribute the subject movies worldwide.

- Secondary Distribution and Fund Flow: Producer F Co. also entered into a secondary distribution agreement with Distributor D Co. Under this agreement, Producer F Co. paid approximately USD 60 million (an amount equivalent to E Partnership's loan from Lender E Bank) to Distributor D Co., and in return, Distributor D Co. granted the movie distribution rights (which it had just obtained from E Partnership) back to Producer F Co.

X's Tax Treatment and the Tax Authorities' Challenge

X, based on its participation in E Partnership, accounted for its share of the movie acquisition cost (approximately 450 million yen) on its books as "equipment and fixtures." Believing these movie rights to be depreciable assets, X proceeded to claim depreciation expenses, opting for a short useful life of two years. This resulted in a depreciation deduction of approximately 154 million yen in its corporate tax return for the fiscal year ending October 1989, with similar deductions claimed in subsequent years. The availability of accelerated depreciation was a key tax benefit sought by the investors.

The tax authorities (initially the Kita Tax Office Chief, later succeeded by Y, the Nishinomiya Tax Office Chief) challenged this treatment. They issued corrective corporate tax assessments and underpayment penalties, denying X's claimed depreciation deductions. The initial grounds for denial by the tax office was that the substantive owner of the movies was Distributor D Co. (or effectively Producer F Co.), not E Partnership.

Lower Court Proceedings

- Osaka District Court (First Instance): The tax authorities argued that the transaction was, in substance, merely a financing arrangement by X (via E Partnership) for Producer F Co.'s movie production, not a genuine acquisition of movie rights by E Partnership. They contended the "sale" to E Partnership was either legally unformed or invalid as a true sale. The District Court agreed with the tax authorities. It found that E Partnership (and thus X) did not genuinely acquire ownership or other effective rights in the movies. The contractual language suggesting E Partnership's ownership was deemed a mere formality designed for tax avoidance by the partners.

- Osaka High Court (Appellate Court): The tax authorities introduced a more explicit argument of "denial based on fact-finding and private law legal construction," effectively asking the court to look through the scheme's form to its underlying economic and legal reality. The High Court largely upheld the District Court's decision. It stated that even without specific anti-avoidance provisions in the tax law, transactions entered into for tax avoidance purposes should be taxed based on the true legal arrangement intended by the parties. The High Court concluded that Producer F Co.'s objective was to raise funds while retaining essential control over the movies, whereas E Partnership's (and its partners') sole objective was tax avoidance.

X, the plaintiff company, appealed these decisions to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis: Focusing on "Use in Business"

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal (except for a procedural rejection of a part related to a later fiscal year for which appeal reasons were not properly submitted), thereby upholding the tax authorities' denial of the depreciation deductions. However, the Supreme Court's reasoning took a more focused path than the broader anti-avoidance pronouncements of the lower courts.

The Supreme Court zeroed in on a fundamental requirement for claiming depreciation under Japanese tax law: the asset must be a "depreciable asset" as defined in Article 31, Paragraph 1 of the Corporate Tax Act (pre-2001 amendment). This provision, in essence, requires that the asset be "used for the business" (jigyō no yō ni kyōshite iru mono) of the taxpayer (or, in this case, the partnership).

The Court's reasoning unfolded as follows:

- Substantive Transfer of Rights Away from E Partnership: The Court acknowledged that E Partnership might have formally acquired "ownership or other rights" to the subject movies through the purchase agreement with Intermediary Seller C Co. However, it immediately pointed out that "almost all rights concerning the subject movies were transferred to Distributor D Co. by the subject distribution agreement, which was concluded on the same date as the subject sale agreement."

The rights transferred to Distributor D Co. were extensive, including the right to choose or change movie titles, edit the films, release them worldwide, create videotapes, handle advertising, and take action against copyright infringement. Distributor D Co.'s rights were not to be affected by any termination or breach of the distribution agreement by E Partnership, and Distributor D Co. could assign its contractual position and even had an option to purchase the movie rights outright. Conversely, E Partnership was severely restricted: it could not limit Distributor D Co.'s rights or terminate the distribution agreement even if Distributor D Co. breached its obligations, nor could it transfer the movie rights to a third party in a way that would adversely affect Distributor D Co.'s rights. - Effective Loss of Control, Use, and Benefit: As a result of this immediate and comprehensive transfer of rights to Distributor D Co., the Supreme Court concluded that E Partnership "had, in substance, lost the authority to use and derive benefit from, and the power to dispose of, the subject movies."

- Lack of Real Economic Risk for E Partnership: The Court highlighted that E Partnership was structured to bear no substantial risk concerning the repayment of the large loan from Lender E Bank (which accounted for about three-quarters of the movie purchase price). The repayment terms of this loan were matched by the minimum guaranteed payments E Partnership was to receive from Distributor D Co. under the distribution agreement. Furthermore, a significant portion of Distributor D Co.'s payment obligations to E Partnership was guaranteed by "Guarantor G Bank."

- Lack of Genuine Business Interest by Partners: The Court also considered the nature of the investors in E Partnership. X, for instance, was a real estate company with no prior experience or involvement in movie production or distribution. The information provided to X by ML Solicit Co. during the investment solicitation reportedly lacked specific details about the movies themselves, including their titles or concrete distribution plans. This suggested that the partners, including X, "did not have an interest commensurate with their investment in the profits that the movie distribution business itself might generate."

- Movies Not a Source of Income for E Partnership's Business: Taking all these factors into account—the immediate transfer of nearly all substantive rights, the lack of real economic risk in the financing, and the partners' lack of genuine interest or involvement in the movie distribution business—the Supreme Court found that "the subject movies cannot be regarded as a source of income in the business of the subject partnership."

- Not "Used for the Business" and Therefore Not Depreciable: Consequently, the Court concluded that the subject movies were "not being used for the business of the subject partnership." As such, they "cannot be recognized as depreciable assets" within the meaning of Article 31, Paragraph 1 of the Corporate Tax Act.

Judgment and Its Significance

Because the movies did not qualify as depreciable assets of E Partnership, X was not entitled to deduct its share of the depreciation expenses. The Supreme Court thus found that the High Court's conclusion (denying the depreciation) was ultimately correct, even if its reasoning pathway differed.

The "Palazzina Case" is a landmark for several reasons:

- Focus on Economic Substance and "Use in Business": The Supreme Court's decision demonstrates a clear focus on the economic substance of the arrangements rather than merely their legal form. It specifically honed in on the statutory requirement that an asset must be "used for the business" to be depreciable. Even if nominal ownership could be argued, the lack of substantive control, risk, and potential for business-related profit from the asset itself led to the denial of depreciation.

- Judicial Scrutiny of Tax Shelters: This ruling was a significant blow to the type of tax shelter that sought to create large, often accelerated, tax deductions (like depreciation) for investors who bore little real economic risk and had no genuine operational involvement with the underlying assets or business activity.

- Avoiding Broad Anti-Avoidance Doctrines: Notably, the Supreme Court reached its conclusion by applying a specific statutory requirement (the "used for business" test for depreciable assets). It did not explicitly endorse or rely on the broader and more contentious anti-avoidance theories that the lower courts had discussed, such as recharacterizing the entire transaction as mere financing based on subjective intent or applying a general doctrine of "denial based on fact-finding and private law legal construction" solely for tax avoidance motives. This targeted approach, focusing on existing statutory language, is characteristic of the Japanese Supreme Court's traditional caution in overtly creating judicial anti-avoidance doctrines without explicit legislative backing.

- Implications for Asset Ownership in Tax Law: The case suggests that for tax depreciation purposes, formal legal title or ownership may not be sufficient if it is divorced from the practical realities of control, risk, and the ability to generate income from the asset within the taxpayer's purported business.

The "Palazzina Case" serves as a critical example of how Japanese courts may scrutinize complex financial arrangements designed to achieve tax benefits. While the Court did not articulate a general anti-tax avoidance rule, its pragmatic assessment of whether an asset is truly integrated into a taxpayer's business operations to generate income provides a potent tool for tax authorities to challenge schemes that lack economic substance. It highlights that for an asset to be depreciable, it must be more than just a passive entry on a balance sheet; it must be a working component of the taxpayer's actual business endeavors.