Subsidiary's Purchase of Parent Stock: Piercing the Veil on Treasury Share Prohibitions in Japan

Judgment Date: September 9, 1993

Case: Action Seeking Enforcement of Directors' Liability (Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench)

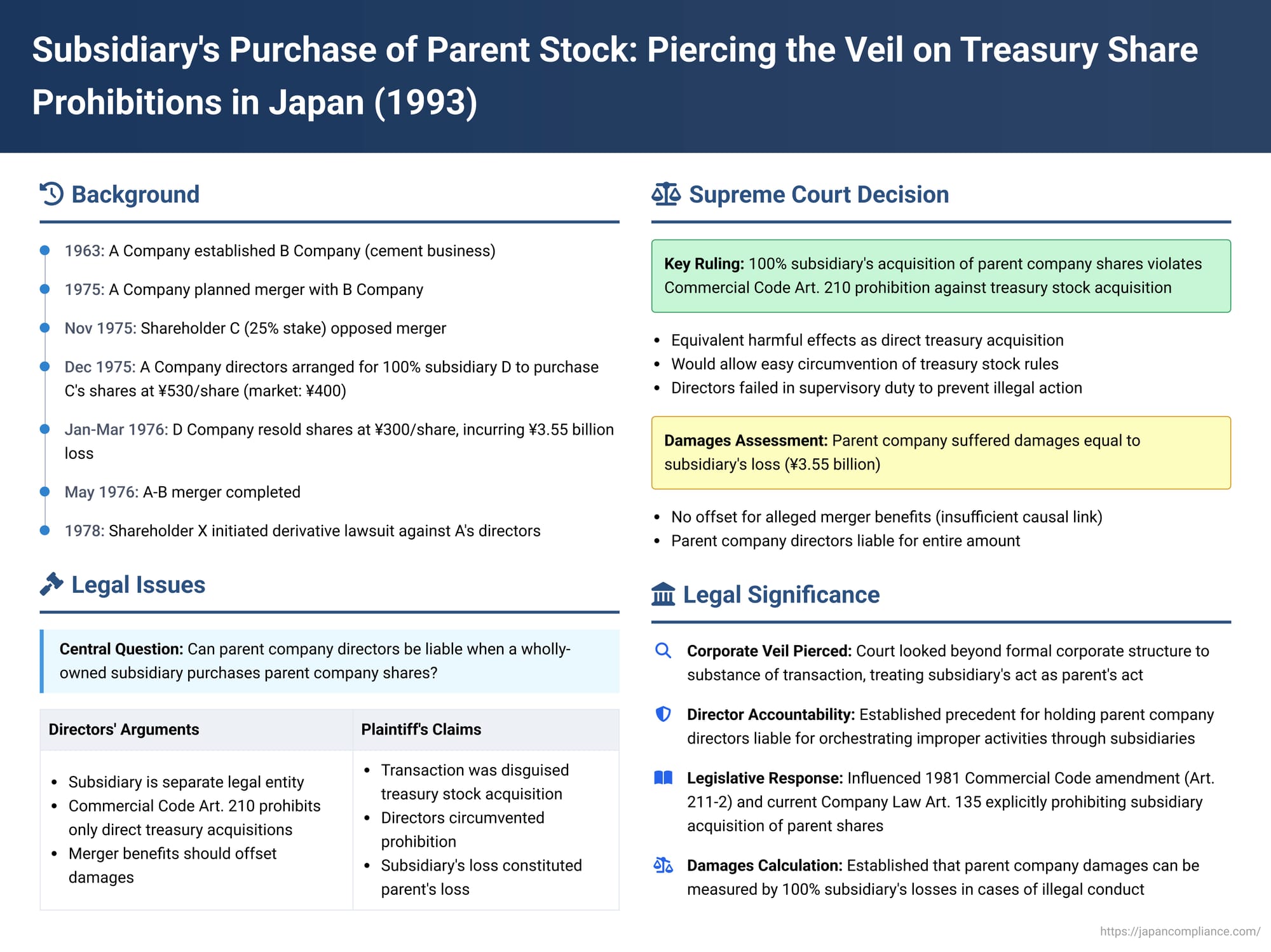

This influential 1993 Japanese Supreme Court decision addressed the liability of parent company directors when a wholly-owned subsidiary purchased shares of its parent company, resulting in a significant financial loss. At a time when Japanese law strictly limited companies from acquiring their own shares (treasury stock), this case explored whether such an acquisition by a 100% subsidiary could be equated to a prohibited act by the parent itself.

Factual Background: A Merger, a Resistant Shareholder, and a Subsidiary Buyout

The case revolved around A Company, originally a mining enterprise that was seeking to diversify its operations due to declining performance in the 1960s. As part of this strategy, A Company, along with other affiliated entities, established B Company in 1963 to focus on the cement business.

- Proposed Merger and Shareholder Opposition: By 1975, B Company's performance had stabilized, and its market share had grown. A Company's management began planning to absorb B Company through a merger. This move was intended to make the cement business A Company's core operation and to consolidate its dispersed shareholder base. However, C, a significant shareholder who had been acquiring A Company stock since around 1972 and by mid-November 1975 held at least 15.5 million shares (approximately 25% of A Company's total issued shares), voiced opposition to the merger. C feared a dilution of their shareholding ratio if the merger proceeded. This opposition put the necessary two-thirds special resolution for the merger at the A Company shareholders' meeting in jeopardy.

- The Buyout Plan: Despite repeated negotiations, A Company's management could not persuade C to support the merger. Consequently, on December 3, 1975, A Company's executive committee devised a plan: D Company, a wholly-owned (100%) subsidiary of A Company, would purchase C's shares in A Company. This purchase would be at a price significantly above the prevailing market rate (around JPY 530 per share, compared to the market price of approximately JPY 400). The shares would then be resold to various A Company group affiliates at a lower price, with D Company absorbing the resulting financial loss.

- Execution and Loss: Following the executive committee's decision, on December 4, 1975, D Company purchased the 15.5 million A Company shares (referred to as "the shares") from C for a total of JPY 8.215 billion. Between January and March 1976, these shares were sold to A Company's group affiliates for approximately JPY 300 per share. This series of transactions resulted in a substantial loss of JPY 3.5516 billion for D Company. The merger between A Company and B Company was subsequently approved at an extraordinary shareholders' meeting of A Company and became effective on May 1, 1976.

- Shareholder Derivative Suit: In 1978, X, who had acquired 1,000 shares of A Company, initiated a shareholder derivative lawsuit against Y1 through Y18, who were directors of A Company at the time of the share purchase. X alleged that D Company's acquisition of A Company shares violated Article 210 of the Commercial Code (as it stood at the time), which generally prohibited companies from acquiring their own shares, save for specific exceptions. X claimed that the JPY 3.55 billion loss incurred by D Company effectively constituted a loss for A Company. The lawsuit sought JPY 100 million in damages from the directors.

- Lower Court Rulings: The court of first instance found six of the directors (Y1-Y6), who were members of the executive committee or had attended its crucial meeting, liable. The remaining directors (Y7-Y18) were dismissed from the suit as they were not found to be involved in the share acquisition. The liable directors appealed. The High Court upheld the first instance decision, emphasizing that acquiring treasury stock was permissible only under narrowly defined statutory exceptions or in situations type-typically free of harm. It rejected the argument that such an acquisition could be justified even if deemed necessary to achieve a critical corporate benefit or avoid significant harm. The High Court also denied the directors' attempt to offset any alleged benefits from the subsequent merger against the calculated loss. The directors then appealed to the Supreme Court, adding new arguments, including that D Company's loss should not be directly equated with A Company's loss.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Parent Company Directors Held Liable

The Supreme Court dismissed the directors' appeal, affirming the lower courts' findings.

- No Abuse of Shareholder Rights: The Court first upheld the High Court's determination that X's initiation of the derivative lawsuit did not constitute an abuse of rights.

- Illegality of Parent Share Acquisition by a 100% Subsidiary: The Court laid down a crucial principle:

The acquisition of shares in a parent company by its wholly-owned subsidiary (the judgment's generic phrasing was "Company A acquiring shares of Company B, where Company B wholly owns Company A," which by analogy applies to a subsidiary buying its parent's shares) is prohibited under Article 210 of the Commercial Code (pre-1981 amendment), unless specific statutory exceptions are met or other special circumstances exist, such as a gratuitous acquisition.- Rationale: Such an acquisition by the subsidiary poses the same potential harms (e.g., market manipulation, preferential treatment of certain shareholders, depletion of corporate assets) as if the parent company were acquiring its own shares directly. Moreover, permitting such transactions would allow companies to easily circumvent the regulations on treasury stock acquisition by using their wholly-owned subsidiaries.

Applying this principle, the Court found that D Company's acquisition of A Company shares was in violation of Article 210.

- Rationale: Such an acquisition by the subsidiary poses the same potential harms (e.g., market manipulation, preferential treatment of certain shareholders, depletion of corporate assets) as if the parent company were acquiring its own shares directly. Moreover, permitting such transactions would allow companies to easily circumvent the regulations on treasury stock acquisition by using their wholly-owned subsidiaries.

- Parent Company's Loss and Causation:

The Court affirmed the High Court's assessment of damages:- D Company's assets were depleted by JPY 3.5516 billion—the difference between the purchase price and the subsequent sale price of the A Company shares.

- In the absence of special circumstances, A Company, being the sole shareholder of D Company, suffered an equivalent reduction in its own assets and, therefore, incurred damages amounting to the same sum.

- A clear causal relationship existed between the damages suffered by A Company and D Company's acquisition of the shares.

Thus, the lower court's finding that A Company suffered JPY 3.5516 billion in damages was upheld.

- Rejection of Profit Set-Off: The Supreme Court also concurred with the High Court's refusal to allow any alleged profits from the subsequent merger to be set off against A Company's damages, deeming the causal link insufficient.

Analysis and Implications: Scrutinizing Corporate Group Transactions

This 1993 Supreme Court decision was a significant ruling on director liability in the context of intra-group transactions designed to overcome corporate governance challenges, particularly concerning the then-strict rules against treasury stock acquisition.

1. Significance in Evolving Corporate Law:

The case was pivotal because it effectively held parent company directors accountable for actions taken by a wholly-owned subsidiary that were deemed equivalent to the parent itself engaging in a prohibited act—the acquisition of its own shares. At the time, Article 210 of the Commercial Code strictly limited treasury stock acquisitions. While a specific statutory provision prohibiting subsidiaries from acquiring parent company shares was introduced in a 1981 Commercial Code amendment (Article 211-2, the principles of which are now in Article 135 of the current Company Law), this 1993 judgment remains a key precedent for understanding director liability, especially if current rules under Company Law Article 135 are violated. It's worth noting that Japanese regulations on treasury stock acquisition have been significantly relaxed since this judgment. Today, if the parent company itself could have legally acquired its own shares (by adhering to current procedural and financial source regulations), the analysis of a similar factual scenario might differ.

2. Abuse of Rights in Derivative Lawsuits:

The Supreme Court's affirmation of the lower court’s narrow interpretation of what constitutes an abuse of rights in filing a derivative lawsuit is generally seen as appropriate, supporting the vital role of such lawsuits in corporate governance.

3. Illegality of a 100% Subsidiary Acquiring Parent Shares (under pre-1981 law):

Prior to the 1981 Commercial Code amendment explicitly addressing this, the unanimous view among legal scholars was that a 100% subsidiary acquiring its parent company's shares was tantamount to a prohibited treasury stock acquisition by the parent and thus violated Article 210. This was due to the identical potential for negative consequences, such as impairment of capital maintenance or market manipulation. The Supreme Court's decision aligned with this prevailing academic consensus, permitting such acquisitions only under the narrow statutory exceptions where such harms were type-typically absent.

Under current Company Law, Article 135 directly prohibits, with certain exceptions, a subsidiary from acquiring shares in its parent company. A key question is whether such an acquisition today would only constitute a violation of Article 135 (which primarily attracts an administrative non-penal fine) or could also be treated as a violation of the parent company's own treasury stock acquisition rules (potentially involving criminal penalties if financial source regulations are breached). Even if deemed subject to treasury stock regulations, penalties would likely be reserved for situations directly comparable to the parent breaching financial source rules.

4. Determining the Parent Company's Loss:

The Court's decision regarding A Company's loss sparked considerable discussion:

- Equating Subsidiary's Loss with Parent's Loss: Some commentators raised concerns that allowing the parent company (A) to claim damages for a loss directly incurred by its subsidiary (D) could be problematic from the perspective of D Company's creditors. They argued that D was the immediate victim. However, the ruling does not preclude D's creditors from pursuing D's own directors for mismanagement. The liability of A Company's directors to A Company for the loss it suffered through the diminution in D's value is not necessarily contradictory to other potential claims. Given the complete ownership and economic integration between a parent and its 100% subsidiary, equating the subsidiary's asset reduction with the parent's loss is generally accepted in the absence of overriding special circumstances. From a more technical accounting or legal standpoint, the parent's loss could be framed as the impairment in the value of its shareholding in the subsidiary.

- Calculating the Quantum of Damages: The method used to calculate damages (D Company's purchase price of A Company shares minus D's sale price of those shares) was also critiqued. Some argued that this method did not adequately account for general market price fluctuations of A Company's shares that were not attributable to the directors' wrongful actions. However, the Supreme Court, viewing the initial illegal acquisition and the subsequent resale as parts of a single, predetermined strategy to address the C's opposition, found this calculation method justifiable. It's important to note that methods for calculating damages in cases of illegal treasury stock acquisitions vary, with a more recent prominent view suggesting damages should be the difference between the fair market value at the time of acquisition and the actual price paid, if higher.

- Rejection of Benefit Set-Off (損益相殺 - Son'eki Sosai): The directors argued that any financial benefits A Company gained from the successful merger (which the share buyout facilitated) should be offset against the damages. The Supreme Court, like the High Court, rejected this argument. While, in principle, profits arising from an illegal transaction might be considered when calculating net damages, the courts found it difficult in this instance to establish a direct causal link between the illegal share buyback operation and A Company's improved performance post-merger.

Conclusion: Judicial Vigilance Over Circumvention of Corporate Norms

The 1993 Supreme Court judgment stands as a significant marker in Japanese corporate law, demonstrating judicial willingness to look beyond formal corporate structures to address substantive breaches of corporate regulations. It confirmed that, at the time, a wholly-owned subsidiary's acquisition of its parent company's shares could be treated as a prohibited treasury stock acquisition by the parent itself, holding the parent's directors accountable for the ensuing financial losses. This decision underscores the courts' role in scrutinizing transactions that may be structured to circumvent legal norms, even when conducted through legally distinct entities within a corporate group.