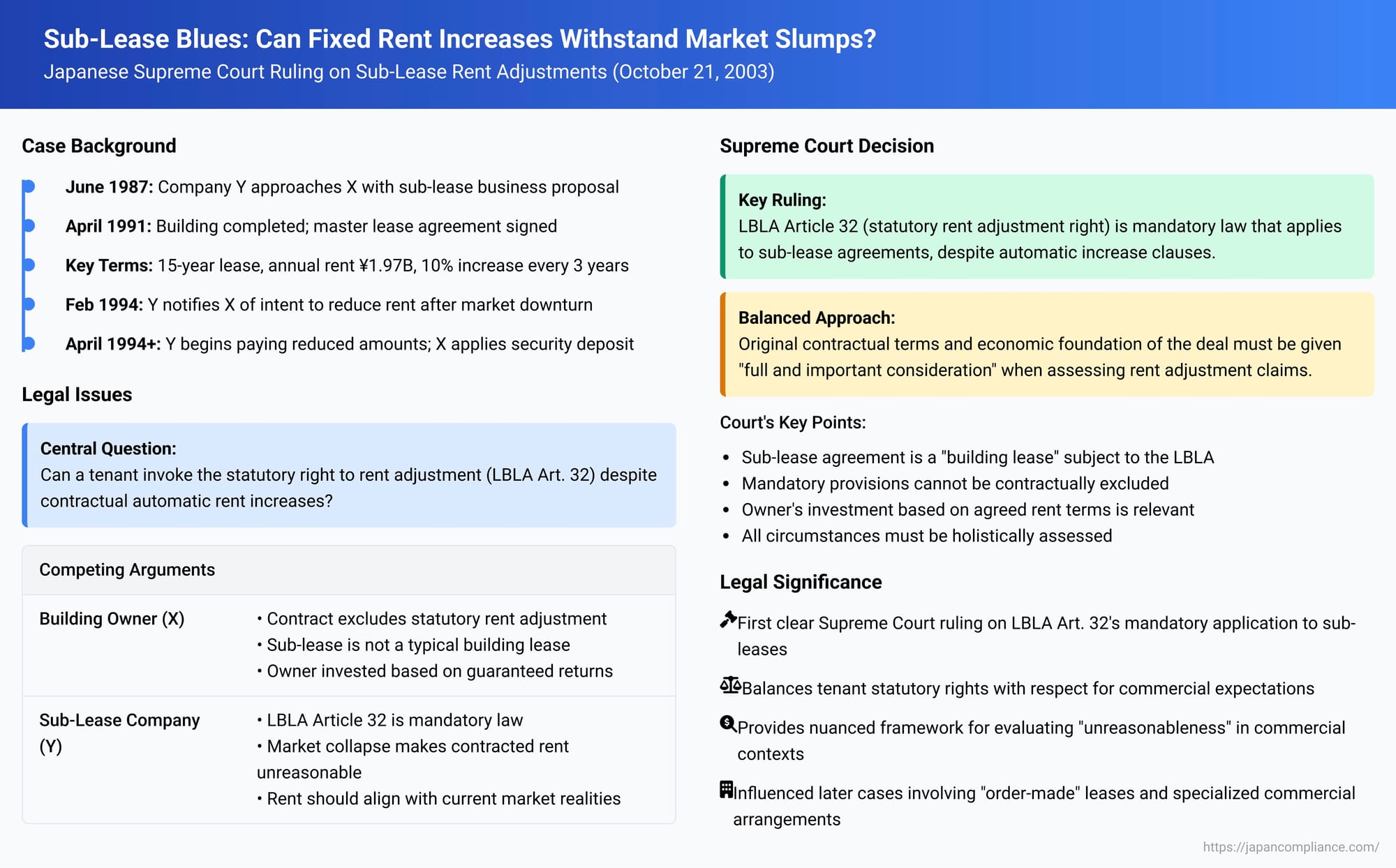

Sub-Lease Blues: Can Fixed Rent Increases Withstand Market Slumps? A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: October 21, 2003

Case Name: Claim for Security Deposit (Main Suit), Counterclaim for Confirmation of Rent Amount

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

"Sub-lease" or "master lease" arrangements have become a common feature in Japan's commercial real estate landscape. In a typical setup, a property owner leases an entire building (or a significant portion of it) to a specialized "sub-lease" company. This company then takes on the responsibility of finding and managing end-tenants, aiming to provide the property owner with a stable, long-term rental income, often with built-in rent increases. However, what happens when economic conditions sour, and the rent payable by the sub-lease company to the owner, particularly if subject to automatic escalations, becomes significantly misaligned with the income the sub-lease company can generate from actual tenants? A landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on October 21, 2003, addressed this critical issue, focusing on the applicability of statutory rent adjustment rights under Japan's Land and Building Lease Act (LBLA).

The Grand Design: A Building Owner and a Sub-Lease Operator

The case involved a large-scale commercial property and a sophisticated sub-lease structure:

- The Initial Agreement: In June 1987, X (the eventual building owner) was approached by Y (a major Japanese real estate company) with a proposal. Y suggested that it operate a sub-leasing business in a new building to be constructed by X on X's land, with the arrangement designed to guarantee X a steady and long-term income stream.

- Building Completion and Master Lease: The building (the "Subject Building") was completed in April 1991. X (as owner and head-lessor) and Y (as head-lessee and sub-lessor) then formalized their relationship through a comprehensive master lease agreement (the "Subject Agreement") for the rentable portions of the building (the "Leased Premises").

- Key Terms of the Master Lease:

- Y would lease the entire Leased Premises from X and then sub-lease individual units to end-tenants at its own risk and expense, managing the property as a commercial office building.

- The lease term was 15 years, with provisions for a further 15-year renewal upon consultation. Early termination was heavily restricted.

- The initial annual rent payable by Y to X was set at a substantial ¥1,977,400,000.

- Crucially, the agreement included an "Automatic Rent Increase Clause": the rent would increase by 10% of the immediately preceding rent amount every three years.

- It also contained an "Adjustment Clause": if the agreed 10% increase rate became unreasonable due to events like rapid inflation or other significant economic shifts, the parties could negotiate to modify this rate.

- Y provided a massive security deposit to X, amounting to ¥4,943,500,000.

- X reportedly relied on this projected rental income stream (including the automatic increases) to secure financing for the building's construction.

- Economic Downturn and Rent Disputes: Following a significant downturn in the Japanese real estate market (likely after the "bubble economy" burst), Y found it difficult to achieve the rental income from end-tenants that was anticipated when the high master lease rent and escalation clauses were set.

- Starting in February 1994, and on several subsequent occasions, Y formally notified X of its intention to reduce the rent it paid to X for the Leased Premises.

- From April 1994 onwards, Y began paying X amounts lower than the rent stipulated by the Subject Agreement (which would have included the 10% triennial increases).

- Litigation: X, asserting that the full agreed rent (including automatic increases) was due, applied Y's security deposit to cover the alleged shortfalls and accrued late payment charges. X then sued Y to compel Y to replenish the drawn-down security deposit and pay ongoing rent arrears. Y, in turn, filed a counterclaim, seeking a court declaration that the rent had been validly reduced pursuant to Article 32, Paragraph 1 of the Land and Building Lease Act (LBLA). This statutory provision grants tenants (and landlords) the right to request an adjustment (decrease or increase) of rent if the existing rent becomes unreasonable due to changes in economic circumstances, such as fluctuations in land or building values or comparisons with rents of similar properties in the vicinity.

- Lower Court Rulings:

- The Tokyo District Court ruled entirely in favor of X (the owner). It held that the parties had, through their sophisticated agreement (which included a form of rent guarantee by Y), effectively excluded the application of LBLA Article 32. It also suggested the arrangement wasn't a typical building lease to which Article 32 would straightforwardly apply.

- The Tokyo High Court took a more nuanced approach but still largely favored X. It characterized the Subject Agreement as not a standard lease, implying the LBLA shouldn't apply wholesale. It found that LBLA Article 32(1) was applicable only in a modified and limited sense, primarily through the lens of the contract's "Adjustment Clause." The High Court interpreted Y's rent reduction demands as requests to modify the rate of increase under this Adjustment Clause, deeming that the 10% increase rate had effectively been reduced to 0% at the times Y made its demands, but not allowing for a reduction below the then-current rent level.

Both parties sought review by the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court Steps In

On October 21, 2003, the Supreme Court quashed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for reconsideration, providing crucial clarifications on the application of LBLA Article 32 to such sub-lease master agreements.

Core Rulings of the Supreme Court:

- Master Lease is a "Building Lease" Subject to LBLA: The Court stated unequivocally that the Subject Agreement between X and Y was, in its legal form and substance, a contract for the lease of a building. As such, the provisions of the Land and Building Lease Act, including Article 32, were applicable.

- LBLA Article 32(1) is Mandatory Law: The Supreme Court emphasized that Article 32(1) of the LBLA, which provides the right to request rent adjustments, is a mandatory provision (強行法規 - kyōkō hōki). This means its application cannot be contractually excluded by the parties. Therefore, even the presence of the Automatic Rent Increase Clause in the Subject Agreement did not prevent either party from exercising their statutory right to seek a rent modification if the conditions of Article 32(1) were met.

- Assessing Rent Reduction Claims in Sub-Lease Contexts – A Balanced Approach: While affirming the applicability of Article 32(1), the Supreme Court provided detailed guidance on how such rent reduction claims should be evaluated in the specific context of these large-scale sub-lease arrangements:

- Importance of the Original Deal's Foundation: The Court acknowledged that the initially agreed-upon rent level and the Automatic Rent Increase Clause were not arbitrary. They were critical components of the agreement, forming the very basis upon which X (the owner) undertook the significant capital investment to construct the building for Y's (the sub-lessor's) sub-leasing enterprise. These factors were central to the parties' original bargain.

- Equitable Considerations: From an equitable standpoint (衡平の見地 - kōhei no kenchi), these original contractual elements and the circumstances surrounding their agreement must be given full and important consideration when determining:

- Whether a rent reduction claim under Article 32(1) is justified (i.e., whether the statutory conditions for exercising the right, such as the rent becoming "unreasonable," are actually met).

- What the "fair and appropriate" adjusted rent amount should be.

- Comprehensive Assessment of All Circumstances: The determination requires a holistic review of all relevant factors, including:

- The historical background of how the initial rent was determined and the reasons for including the automatic increase mechanism.

- The relationship between the originally agreed rent and prevailing market rents for comparable properties at the time the contract was made (including the extent of any initial deviation from market rates).

- Factors related to Y's (the sub-lessor's) projected revenues and expenditures for its sub-leasing business, including the parties' initial understanding of how the proportion of Y's master lease payments to X, compared to Y's rental income from end-tenants, was expected to change over time.

- X's (the owner's) financial plans and commitments, such as the repayment schedule for the security deposit received from Y and any bank loans X took out for the building's construction, which were predicated on the agreed rental income.

A supplementary opinion by one of the Justices further elaborated on why such sub-lease agreements should, as a starting point, be treated as leases subject to the LBLA, rather than being readily categorized as distinct "innominate contracts" that fall outside the Act's scope, arguing that equitable solutions can usually be found within the existing legal framework.

Navigating the Nuance: What Does This Mean?

This Supreme Court judgment was a landmark, representing the first clear pronouncement from the nation's highest court on the direct applicability of LBLA Article 32 to sub-lease master agreements and its overriding, mandatory nature in the face of fixed rent escalation clauses.

Context and Academic Debate

Prior to this ruling, lower courts had adopted varied stances on applying LBLA Article 32 to sub-lease agreements, ranging from direct application to modified application, or even complete denial of its relevance. Academic theories also differed on how to legally characterize these complex arrangements and the payments involved. The Supreme Court's decision provided significant clarification.

Evaluating the Supreme Court's Approach

The ruling is generally seen as affirming that such sub-lease master agreements are indeed a form of building lease and thus fall under the purview of LBLA Article 32. However, by stressing the need to give "full and important consideration" to the original contractual terms and the economic basis of the deal (especially the owner's investment reliant on the agreed rent stream and the sub-lessor's business plan), the Court effectively signaled that a rent reduction under Article 32 is not an automatic entitlement merely because market rents have fallen. The threshold for proving that the agreed rent has become "unreasonable" and the extent of any reduction granted may be significantly influenced by these initial deal-specific factors. It suggests a more nuanced and fact-intensive inquiry than might occur in a simpler, standard bilateral lease.

Scope of Application

The principles articulated in this 2003 sub-lease case have been seen as influential in other contexts as well. For instance, similar reasoning had been applied by the Supreme Court to ground rent revision clauses in land leases earlier the same year. Subsequent Supreme Court cases involving "order-made leases" (where a building is constructed or customized to a specific tenant's requirements, often involving significant upfront investment by the owner based on a long-term lease commitment) have also appeared to follow a similar analytical framework, emphasizing the importance of the initial investment and agreed terms when considering statutory rent adjustment claims.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2003 decision in this sub-lease case confirmed that the statutory right of tenants (and landlords) to seek rent adjustments under Article 32 of the Land and Building Lease Act is a mandatory provision that applies even to sophisticated, large-scale commercial sub-lease (or master lease) agreements. It cannot simply be contracted out of by automatic rent increase clauses. However, the ruling also strongly mandates that the unique economic realities, initial investment assumptions, and specific bargained-for terms that formed the foundation of these complex commercial ventures must be given substantial weight in assessing whether the conditions for a rent adjustment are met and what a fair adjusted rent would be. This approach seeks to balance the protective aims of the LBLA with the legitimate commercial expectations and risk allocations inherent in such specialized leasing arrangements, requiring a careful, fact-specific analysis in each case.