Japan’s Childcare & Family Care Leave Reforms: A Practical Guide to Work-Life Balance

TL;DR

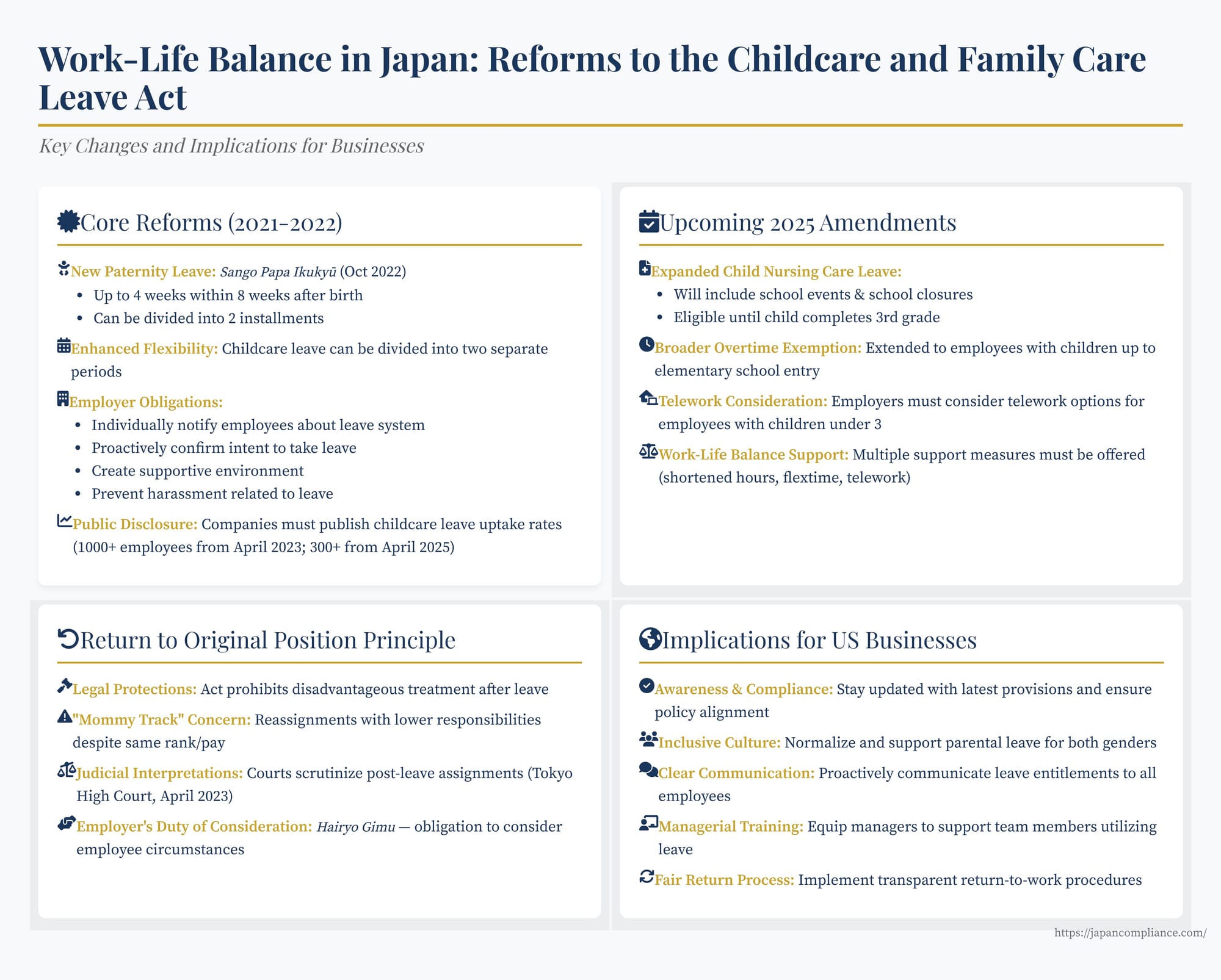

Reforms to Japan’s Childcare and Family Care Leave Act (2022-2025) introduce postnatal paternity leave, split-period childcare leave, stricter anti-harassment rules, and mandatory disclosure of male leave uptake. US employers must update policies, train managers, and ensure fair reinstatement to stay compliant and competitive.

Table of Contents

- The Core of the Reforms: Encouraging Parental Leave and Flexibility

- "Male Paternity Leave" – The Birth of Sango Papa Ikukyū

- Enhanced Flexibility in Regular Childcare Leave

- Strengthening Employer Obligations

- Public Disclosure of Leave Acquisition Rates

- Relaxed Conditions for Fixed-Term Employees

- The "Principle of Return to Original Position" (Genshoku Fukki Gensoku): A Complex Reality

- Broader Work-Life Balance Challenges and the Path Forward

- Implications for U.S. Businesses

The quest for a sustainable work-life balance (WLB) is a global challenge, but it takes on particular significance in Japan, a nation long characterized by demanding work cultures and deeply ingrained gender roles in caregiving. For U.S. companies operating in Japan, understanding the evolving legal landscape surrounding WLB is crucial not only for compliance but also for attracting and retaining talent, and fostering an equitable and productive workforce. A key piece of this puzzle is the Childcare and Family Care Leave Act (Ikuji Kaigo Kyūgyō Hō), which has seen significant reforms aimed at encouraging shared parental responsibilities and supporting employees in balancing their professional and personal lives.

This article examines the recent amendments to this Act, particularly those stemming from the 2021 revisions that were implemented in stages from 2022, and explores their implications for employers and employees in Japan.

The Core of the Reforms: Encouraging Parental Leave and Flexibility

The 2021 amendments to the Childcare and Family Care Leave Act represent a concerted effort to modernize Japan's approach to parental leave, with a strong emphasis on increasing the uptake of leave by male employees and providing more flexible options for all parents.

1. "Male Paternity Leave" – The Birth of Sango Papa Ikukyū

Perhaps the most notable introduction has been the system commonly referred to as "postnatal paternity leave" (sango papa ikukyū) or, more formally, "childcare leave at time of birth" (shusshōji ikuji kyūgyō). Implemented from October 1, 2022, this scheme allows male employees to take up to four weeks of leave within the first eight weeks after a child's birth. This leave can be taken in two separate installments, offering a degree of flexibility previously unavailable.

The creation of this specific leave aims to address the historically low rates of paternity leave uptake by men in Japan. By carving out a dedicated period and making it more adaptable, the government hopes to make it easier for fathers to be actively involved in childcare from the very beginning. An important feature is that, under certain conditions agreed upon in a labor-management agreement, employees can perform some work during this leave, potentially easing concerns about complete detachment from work responsibilities.

2. Enhanced Flexibility in Regular Childcare Leave

Beyond the new postnatal paternity leave, the reforms also introduced greater flexibility to the standard childcare leave system. Previously, childcare leave (generally available until a child turns one, with extensions possible up to two years under specific circumstances) had to be taken in a single, continuous block per child by each parent. The amendments effective from October 1, 2022, now allow both parents to divide their childcare leave into two separate installments. This change acknowledges that care needs can fluctuate and allows for more tailored arrangements, such as parents taking turns or one parent taking leave, returning to work, and then taking a second period of leave later.

3. Strengthening Employer Obligations

The revised Act places more explicit responsibilities on employers to foster a supportive environment for employees taking childcare leave. Since April 1, 2022, companies have been obligated to:

- Individually Notify and Confirm Intentions: Employers must individually inform employees (or their spouses, in the case of male employees learning of a pregnancy/birth) about the childcare leave system and proactively confirm their intention to take leave. This shifts the onus from the employee solely initiating the process to the employer actively engaging in it.

- Create a Conducive Environment: Companies must take measures to create a workplace environment that makes it easier for employees to apply for and take childcare leave. This can include conducting training for managers and colleagues, establishing consultation services, and clearly communicating company policies and support systems.

- Measures to Prevent Harassment: The law explicitly requires employers to take measures to prevent harassment related to pregnancy, childbirth, and the taking of childcare or family care leave (so-called "maternity harassment" or "paternity harassment").

4. Public Disclosure of Leave Acquisition Rates

To increase transparency and encourage corporate action, a significant measure introduced from April 1, 2023, mandates that companies with over 1,000 permanent employees publicly disclose the status of their employees' childcare leave acquisition annually. This public reporting is intended to act as an incentive for companies to improve their leave uptake rates, particularly among male employees. The threshold for this disclosure requirement is set to expand to companies with over 300 employees from April 2025.

5. Relaxed Conditions for Fixed-Term Employees

Prior to the April 2022 changes, fixed-term contract employees faced stricter eligibility criteria for childcare and family care leave, typically requiring at least one year of continuous employment with the same employer. The reforms abolished this one-year continuous employment requirement for both childcare and family care leave. Now, fixed-term employees are generally eligible if it is not clear that their contract will end before the child reaches 18 months of age (for childcare leave). However, employers can still, through a labor-management agreement, exclude employees who have been employed for less than one year.

The "Principle of Return to Original Position" (Genshoku Fukki Gensoku): A Complex Reality

A critical, and often contentious, aspect of returning from childcare leave in Japan is the expectation or "principle" that employees should be reinstated to their original position or a substantially equivalent one. While this principle is widely acknowledged and forms part of the spirit of the Childcare and Family Care Leave Act, its legal enforceability and practical application can be complex.

- Legal Underpinnings: The Act prohibits disadvantageous treatment of employees on account of their application for or taking of childcare or family care leave. This is a strong protection. If a reassignment upon return is demonstrably a demotion or results in unfavorable working conditions directly linked to the leave, it could be deemed illegal.

- The "Mommy Track" Concern: Despite these protections, there's a persistent concern about employees, particularly women, being placed on a so-called "mommy track" upon returning from leave. This might involve reassignment to a less demanding role, potentially with fewer responsibilities or opportunities for career advancement, even if there is no immediate reduction in salary. While such moves might be framed by employers as considerate of the employee's new family responsibilities, they can inadvertently hinder long-term career progression.

- Judicial Interpretations: Japanese courts have grappled with cases involving reassignments post-leave. If a reassignment involves a clear demotion in rank or a significant cut in pay, it is more likely to be found to be disadvantageous treatment. However, cases where the rank and pay remain nominally the same, but the nature of the work changes or perceived career prospects diminish, are more nuanced. Courts often consider the employer's operational necessities for the reassignment against the extent of the disadvantage to the employee. A Tokyo High Court judgment on April 27, 2023 (reported in Rōdō Hanrei No. 1292, p. 40) found a post-childcare leave reassignment to be illegal, indicating that courts are willing to scrutinize such changes. However, the specific facts of each case, including the nature of the original and new roles, the company's justification, and the actual impact on the employee's career, are heavily weighed.

- Employer's Duty of Consideration (Hairyo Gimu): While not a strict "reasonable accommodation" mandate in the way it exists in some other legal contexts (like for disabilities), employers in Japan are generally expected to give due consideration to an employee's circumstances when they return from leave. This includes discussing the return-to-work arrangements and trying to find a mutually acceptable solution. The 2021 reforms also emphasize the employer's role in facilitating a smooth return, which implicitly includes appropriate placement.

The debate around the "return to original position" often highlights the tension between the employee's right to career continuity and the employer's managerial prerogative regarding personnel placement, a prerogative traditionally held to be quite broad in Japan. The strength of the "principle" often depends on whether a deviation from it can be proven to be a prohibited "disadvantageous treatment."

Broader Work-Life Balance Challenges and the Path Forward

The reforms to the Childcare and Family Care Leave Act are significant steps, but they operate within a broader context of work-life balance challenges in Japan.

- Long Working Hours: Despite efforts towards "work style reform" (hatarakikata kaikaku), a culture of long working hours persists in many sectors. This makes it difficult for all employees, regardless of parental status, to achieve a healthy work-life balance and can be a particular deterrent for fathers considering longer periods of leave.

- Gendered Division of Labor at Home: Societal expectations still place a heavier burden of childcare and housework on women. While the increased emphasis on male parental leave aims to shift this, deep-seated norms change slowly. The true success of WLB initiatives hinges not just on legal entitlements but also on a broader cultural shift towards shared responsibility in the home.

- Uptake Rates and Workplace Culture: The actual uptake of leave, especially by men, remains a key indicator of success. While male childcare leave uptake has been rising (reaching a record 17.13% in the 2022 fiscal year for those in employment insurance, and a reported 30.1% in a 2023 fiscal year survey, though methodologies can vary), it is still far from parity with women. The workplace atmosphere, including the attitudes of superiors and colleagues, plays a crucial role. The legal mandate for employers to create a "conducive environment" is an attempt to address this, but cultural change is an ongoing process.

- Support for Diverse Family Structures and Needs: While the Act focuses on childcare and family care (typically for aging relatives), the broader WLB conversation in Japan is also beginning to encompass the needs of employees with other types of care responsibilities or personal life needs.

Future Outlook: The 2025 Amendments

Further amendments to the Childcare and Family Care Leave Act are scheduled to come into effect in stages, mostly from April 2025. These include:

- Expansion of Child Nursing Care Leave: The scope of "child nursing care leave" (子の看護休暇 - ko no kango kyūka) will be expanded. Currently often used for a child's illness or injury, it will more explicitly cover participation in school events (like entrance/graduation ceremonies) and situations like school closures due to infectious diseases. The eligible age of the child for this leave will also be raised from before elementary school entry to until the child completes the third grade of elementary school. The name is also slated to change to 「子の看護等休暇」 (ko no kango-tō kyūka - child nursing and other matters leave).

- Broader Overtime Work Exemption: The scope of employees eligible for exemption from overtime work will be expanded. Currently, this primarily applies to those with children under three years old. The changes will extend this, under certain conditions, to employees with children up to elementary school entrance.

- Telework as a Consideration: For employees raising children under three years old, employers will have a "duty to endeavor" (努力義務 - doryoku gimu) to offer telework as an option if the employee requests it, as part of flexible working arrangements.

- Strengthened Measures for Balancing Work and Childcare/Family Care: Employers will be required to establish systems for employees to choose from multiple work-life balance support measures (e.g., shortened working hours, flextime, telework, new leave entitlements) until their child reaches a certain age (e.g., three years old or before elementary school). They must also individually inform employees and ascertain their wishes regarding these measures.

- Disclosure of Leave Uptake Expansion: As mentioned, the obligation to publicly disclose male childcare leave uptake rates will extend to companies with more than 300 employees from April 2025.

Implications for U.S. Businesses

For U.S. companies in Japan, these developments underscore the need for:

- Awareness and Compliance: Staying updated with the latest provisions of the Childcare and Family Care Leave Act and ensuring company policies and practices are compliant. This includes internal rules on leave application, notification procedures, and harassment prevention.

- Fostering an Inclusive Culture: Moving beyond mere compliance to actively cultivate a workplace culture where taking parental leave, by both men and women, is normalized and supported without fear of negative career repercussions.

- Clear Communication: Proactively communicating leave entitlements and company support systems to all employees.

- Managerial Training: Equipping managers with the knowledge and skills to support their team members in utilizing leave and managing workloads effectively during absences.

- Fair Return-to-Work Processes: Implementing transparent and fair processes for employees returning from leave, with a genuine effort to reinstate them to their original or equivalent roles, considering career development. This involves open dialogue with the returning employee.

- Monitoring and Adapting: Regularly reviewing internal data on leave uptake and employee feedback to identify areas for improvement in WLB support.

Japan's journey towards better work-life balance is an ongoing process, driven by demographic shifts, a desire for greater gender equality, and the economic imperative to utilize the full potential of its workforce. The recent and upcoming reforms to the Childcare and Family Care Leave Act are critical components of this journey. While challenges in implementation and cultural shifts remain, the direction is clearly towards greater support for working parents and a more equitable sharing of care responsibilities, a trend that all businesses operating in Japan must proactively engage with.