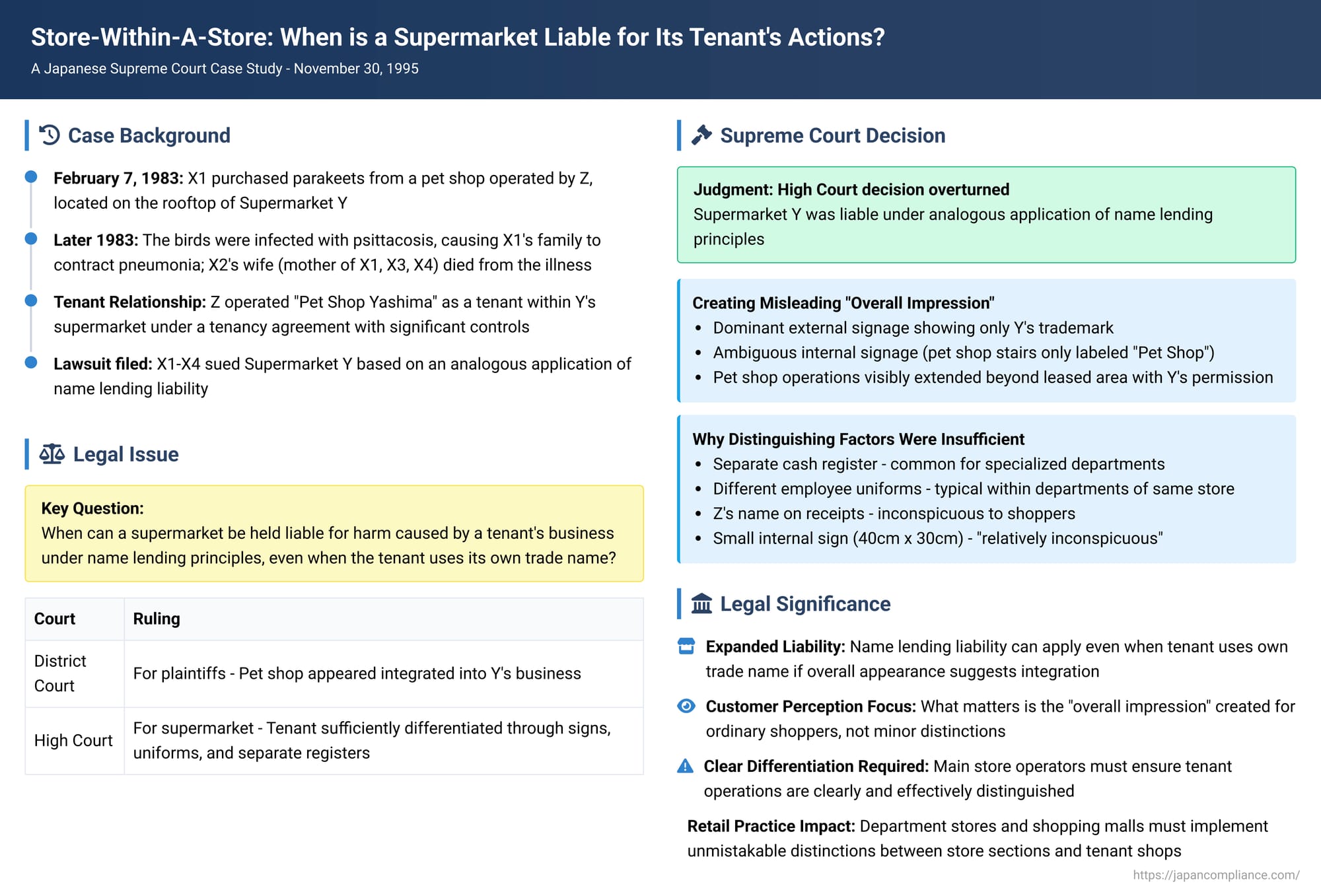

Store-Within-A-Store: When is a Supermarket Liable for Its Tenant's Actions? A Japanese Supreme Court Case Study

Judgment Date: November 30, 1995

The common retail model of larger department stores or supermarkets hosting smaller, independently operated tenant shops within their premises offers convenience to shoppers but can also create ambiguity regarding who is responsible when things go wrong. A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan's First Petty Bench on November 30, 1995 (Heisei 4 (O) No. 1119) delved into this issue, specifically addressing when a supermarket operator can be held liable for harm caused by a tenant's business under an analogous application of "name lending" (名板貸責任 - nabla-gashi sekinin) principles.

The Tragic Incident: Diseased Birds from a Rooftop Pet Shop

The case arose from a tragic incident involving the plaintiffs, X1, X2, X3, and X4 (a family). Around February 7, 1983, X1 purchased two parakeets from a pet shop operated by Z (Mr. Sadao Yashima). Z's pet shop was a tenant business located on the rooftop of a supermarket known as "Y's Sagamihara Store" ("the Store"), which was operated by Company Y (the defendant, originally Chujitsuya, later succeeded by Daiei, and referred to herein as Supermarket Y).

Unfortunately, the parakeets were infected with psittacosis chlamydia (ornithosis). As a result, X1's family members contracted psittacosis pneumonia. Tragically, A, who was X2's wife and the mother of X1, X3, and X4, succumbed to the illness. The surviving family members sued Supermarket Y, as the successor to the original store operator, seeking damages. Their claim was primarily based on an analogous application of Article 23 of the former Commercial Code (provisions now found in Article 9 of the Company Act and Article 14 of the Commercial Code), which deals with the liability of a business that allows another to use its name or trade name, leading third parties to believe they are dealing with the name lender.

The Relationship Between Supermarket Y and Tenant Pet Shop Z

Z operated his pet shop, initially named "Yamamiya Pet Corner" and later "Pet Shop Yashima" or "Yashima Pet," as a tenant within Supermarket Y's premises. The tenancy agreement between Supermarket Y and Z included several key terms:

- Z was permitted to sell only approved items (pets) to maintain the Store's unified business policy and a reasonable balance among tenants, and could not alter these product lines without Supermarket Y's consent.

- The rent comprised a fixed amount plus a variable component based on Z's sales revenue. Supermarket Y managed Z's daily sales receipts, deducted rent, utilities, and other expenses, and then remitted the remainder to Z.

- Z was required to comply with Supermarket Y's regulations regarding business hours, holidays, delivery and removal of goods, cleaning, employee conduct, and other daily operational matters, and to follow Y's instructions on unspecified matters.

The "Outward Appearance": Conflicting Interpretations in the Lower Courts

The crucial legal question was whether Supermarket Y had created, or allowed to be created, an "outward appearance" (外観 - gaikan) that would lead an ordinary shopper to mistakenly believe that Z's pet shop was actually a department of Supermarket Y itself.

- First Instance (Yokohama District Court): The District Court found in favor of the plaintiffs. It held that Z's pet shop operations appeared to be integrated into Supermarket Y's business. The court reasoned that, from the perspective of a general shopper visiting the supermarket, it would be difficult to avoid misidentifying Z's business as Y's own unless clear distinguishing markers were present. Applying Article 23 of the former Commercial Code by analogy, the District Court ruled that Supermarket Y was liable as if it had lent its name to Z.

- Second Instance (Tokyo High Court): The High Court reversed this decision. It focused on the various measures taken to differentiate the tenant from the main store operations. These included:

- Tenant name displays for Z's shop.

- A store directory that distinguished between Y's direct sales areas and tenant shops.

- Different attire for Z's employees compared to Y's staff.

- Z's pet shop having its own distinct payment methods and cash register.

- Z issuing receipts bearing its own shop name.

- Z using different wrapping paper and "paid" stickers from those used by Supermarket Y.

The High Court concluded that these measures, taken together, were sufficient to distinguish Z's business from Y's direct operations. Therefore, it found that Supermarket Y had not created an outward appearance equivalent to allowing Z to use its trade name, and thus, the analogous application of name-lending liability was not appropriate.

The Supreme Court's Decisive Ruling: The "Overall Impression" Is Key

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case, effectively siding with the plaintiffs on the issue of potential liability. The Supreme Court's analysis focused on whether the overall impression created for the average shopper could lead to a reasonable misapprehension about who was operating the pet shop.

Factors Creating a Misleading "Overall Appearance" of Integration:

The Supreme Court identified several facts that contributed to an outward appearance suggesting Z's pet shop was a part of Supermarket Y's operations:

- Dominant External Signage: Large signs displaying Supermarket Y's trademark were prominently featured on the exterior of the Store building, but there was no external display of tenant names.

- Ambiguous Internal Directional Signage: Critically, at the entrance to the staircase leading from the fourth floor to the rooftop (where the pet shop was located), a rooftop guide sign, as well as a sign on the wall of the staircase landing, indicated "Pet Shop" only. These signs did not clarify whether the pet shop was operated by Supermarket Y or by Z.

- Tenant's Expansive Operations with Supermarket's Acquiescence: Z's business activities visibly extended beyond its formally leased area. Price-tagged pet shop goods were placed on the staircase landing leading to the rooftop, and large, handwritten "Big Sale" signs were posted on walls outside Z's contracted space. The Supreme Court noted that Supermarket Y had tacitly permitted these practices. These facts, the Court reasoned, could easily give shoppers the impression that Z's pet shop was merely a department or section of Supermarket Y.

Why Distinguishing Factors Were Deemed Insufficient by the Supreme Court:

The Supreme Court then systematically evaluated the factors that the High Court had considered sufficient to differentiate Z's business, and found them inadequate to dispel the misleading overall impression:

- Separate Cash Register and Sales Method: The Court observed that pets, by their nature, are not typically suited to a supermarket-style self-service sales method. Even if Supermarket Y were selling pets directly, a face-to-face sales approach with a dedicated payment point would likely be used. Thus, Z's separate register did not effectively distinguish it as an independent operator in the eyes of a customer.

- Different Employee Uniforms: The Supreme Court noted that it is common even within different departments of a single large store for employees to wear varied attire depending on the type of goods they handle. The absence of Supermarket Y's specific uniform on Z's staff was not, therefore, a clear indicator of a separate business entity.

- Z's Name on Receipts: Receipts are generally inconspicuous, and shoppers typically do not pay close attention to the formal name printed on them. The Court found this to have minimal value in distinguishing the business operator from an outward appearance perspective.

- Different Wrapping Paper or "Paid" Tape: These differences would only become apparent to a shopper upon comparison with Supermarket Y's materials, and thus did not serve as an immediate external marker of operational independence.

- Z's Small Internal Sign and Color-Coded Store Directory: A small sign (approximately 40cm by 30cm) displaying the tenant's name, hung from the ceiling within Z's sales area, was deemed "relatively inconspicuous." Similarly, while the main store directory did list tenant names (including "Pet Shop Yashima" for the rooftop section) in blue text alongside Supermarket Y's product categories in black text, the Court found that merely differentiating tenant names by color was insufficient to "externally clarify" the distinction of the operating entity for ordinary shoppers.

The Supreme Court's Core Finding and Application of Name Lending by Analogy:

Based on this comprehensive assessment, the Supreme Court concluded:

"In this case, an outward appearance existed such that ordinary shoppers could not be blamed for mistakenly believing that the pet shop operated by Z was operated by Y (the supermarket)."

Furthermore, the Court held that Supermarket Y had "created, or participated in the creation of, this outward appearance" through actions such as displaying its own prominent trademark externally and by the very nature of the tenancy agreement it had concluded with Z (which included terms allowing Y significant control over Z's operations, such as approved product lines and adherence to store rules).

Given this misleading outward appearance and Y's role in it, the Supreme Court ruled that Supermarket Y must bear liability similar to that of a name lender, through an analogous application of Article 23 of the former Commercial Code, for transactions between shoppers and Z. The case was remanded to the Tokyo High Court for further proceedings consistent with this finding.

Analyzing "Name Lending" Liability in Tenant Situations

The doctrine of name-lending liability is designed to protect third parties who transact with a business in reliance on the trade name or reputation of another entity that has permitted its name to be used, or has created an appearance that it is the true operator. This Supreme Court decision is significant because it extended this principle by analogy to a situation where the tenant (Z) was using its own trade name ("Pet Shop Yashima") and was, in fact, likely prohibited by its agreement from using Supermarket Y's name directly for its shop.

The ruling suggests that liability can arise not just from the explicit lending of a trade name, but from the creation of an overall operational environment by the main store operator that reasonably leads customers to believe a tenant's shop is part of the main store's direct business. The Court's approach implies that in large retail environments like supermarkets or department stores that host multiple tenants, there may be an inherent risk of customer confusion regarding the identity of the actual operator of individual sections or shops. Consequently, the onus is on the main store operator (and perhaps the tenant as well) to take active, clear, and effective measures to dispel this potential confusion, rather than relying on subtle or easily overlooked distinctions.

Legal commentary has noted some debate regarding the Supreme Court's reference to Supermarket Y's internal contractual rights to control Z's operations as a factor contributing to the outward appearance relevant to name-lending liability. Critics argue that customers would typically be unaware of these internal contractual details, and such control mechanisms might be more pertinent to assessing vicarious liability (akin to an employer's liability for an employee) rather than name-lending liability, which traditionally focuses on the external signals perceived by the third party. Nevertheless, the Court's primary emphasis remained on the totality of the visible circumstances and the reasonable perception of the ordinary shopper.

Implications for Retailers with In-Store Tenants

This judgment carries important implications for operators of department stores, shopping malls, and supermarkets that lease space to independent tenants:

- Clear Differentiation is Crucial: Main store operators must ensure that tenant operations are clearly and conspicuously differentiated from their own direct sales activities.

- Beyond Basic Signage: Relying on small internal signs, different staff uniforms, or details on receipts may not be sufficient if the overall ambiance and dominant branding suggest integration.

- Managing Customer Perception: Retailers need to consider the overall customer experience and perception. This includes external store branding, internal navigation and departmental signage, and even how tenant spaces are integrated into or separated from the main store layout.

- Potential Liability: Failure to adequately manage this outward appearance can lead to the main store operator being held liable for the defaults or wrongdoings of its tenants, as if the tenant's business were its own.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1995 decision in the "Supermarket Tenant Pet Shop" case serves as a significant precedent in Japanese commercial law. It establishes that a store operator can be held responsible for the actions of an independent tenant operating within its premises if the operator creates or allows an outward appearance that reasonably misleads customers into believing the tenant's business is simply a part of the main store's own operations. This liability can arise by analogy to "name lending," even when the tenant uses its own distinct trade name, if the overall context fails to provide clear and effective differentiation. The ruling underscores the importance for major retailers to proactively ensure that the operational independence of their tenants is unmistakably clear to the shopping public.