Stolen Goods, Good Faith Purchasers, and the Right to Reimbursement in Japan: Balancing Interests Under Civil Code Article 194

Case Reference: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Judgment of June 27, 2000 (Heisei 12) (Case No. 128 (Ju) of 1998 (Heisei 10))

Subject Matter: Main Claim for Delivery of Movables, Counterclaim for Return of Purchase Price (動産引渡請求本訴,代金返還請求反訴事件 - Dōsan Hikiwatashi Seikyū Honsō, Daikin Henkan Seikyū Hanso Jiken)

Introduction

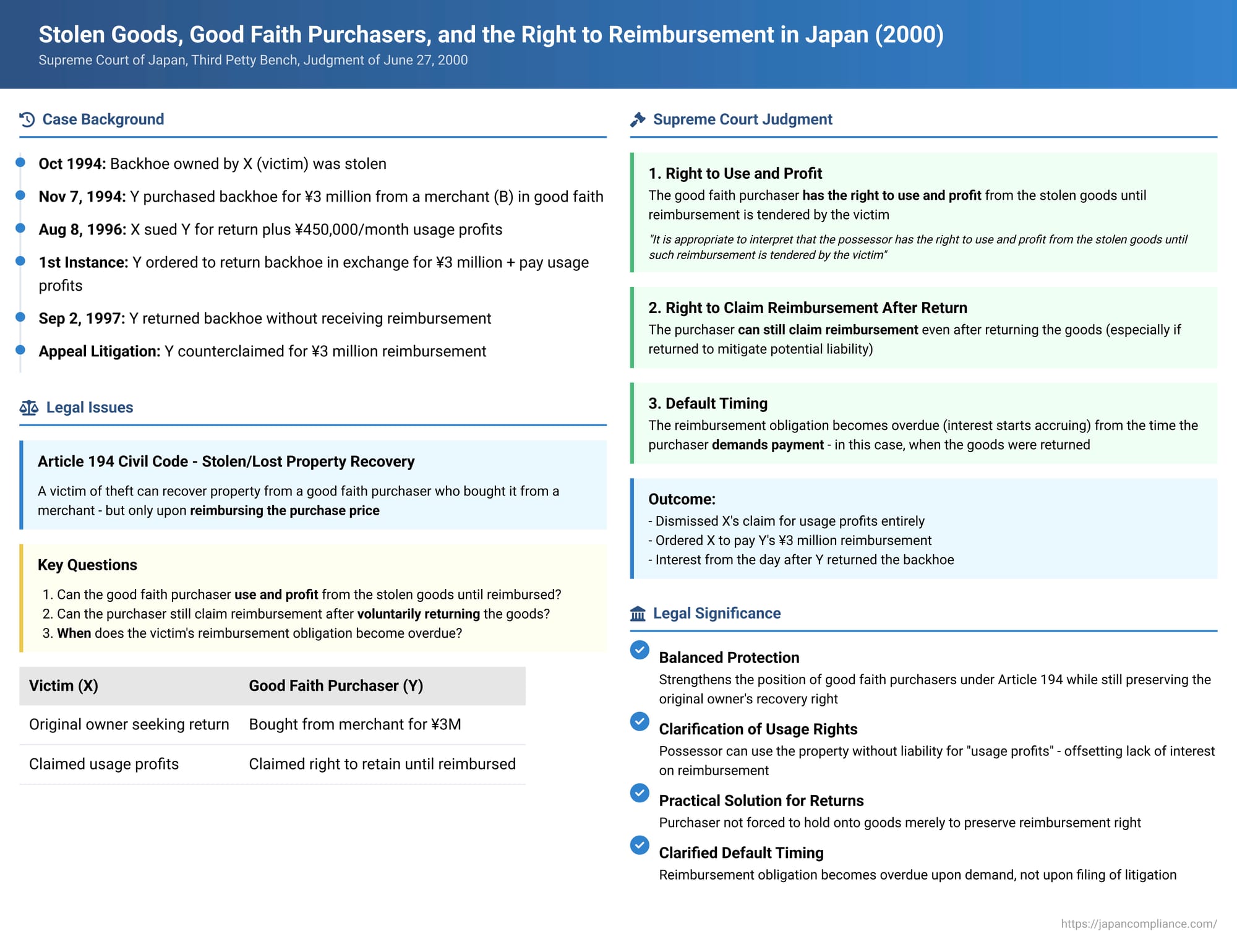

This article examines a 2000 Japanese Supreme Court judgment that provides significant clarifications regarding the rights and obligations of a good faith purchaser of stolen goods under Article 194 of the Civil Code. This provision allows a victim of theft (or loser of property) to recover the goods from a bona fide purchaser who acquired them at an auction, in a public market, or from a merchant selling similar items, but only upon reimbursing the purchaser for the price they paid (代価の弁償 - daika no benshō). The Supreme Court addressed three key issues: (1) whether the good faith purchaser has the right to use and profit from the stolen goods until reimbursed; (2) whether the purchaser can still claim reimbursement if they return the goods before being paid; and (3) when the victim's reimbursement obligation becomes overdue.

The dispute involved X (appellee/plaintiff), the original owner of a stolen backhoe, and Y (appellant/defendant and counterclaimant), who had purchased the backhoe in good faith.

Factual Background

Around the end of October 1994, a backhoe owned by X was stolen by A and others. On November 7, 1994, Y purchased this backhoe for JPY 3 million from B, a merchant dealing in used construction machinery who operated without a physical store. Y paid the price and received delivery of the backhoe, acting in good faith and without negligence regarding B's authority to sell it.

On August 8, 1996, X filed a lawsuit against Y, seeking the return of the backhoe based on ownership and also claiming damages equivalent to the profits from using the backhoe, calculated at JPY 450,000 per month from the day after the service of the complaint until the backhoe was returned. Y contested the claim for usage profits and asserted the right under Article 194 of the Civil Code to retain the backhoe until X reimbursed the JPY 3 million purchase price.

The first instance court ordered Y to return the backhoe to X in exchange for X's payment of JPY 3 million. It also ordered Y to pay X unjust enrichment equivalent to usage profits at a rate of JPY 300,000 per month from the day after service of the complaint until the backhoe was returned. Y appealed this decision, and X filed a cross-appeal.

While the case was pending in the appellate court, on September 2, 1997, Y returned the backhoe to X without having received the JPY 3 million reimbursement. Y did this to avoid the increasing liability for usage profits as ordered by the first instance court. X then withdrew the part of the lawsuit demanding the return of the backhoe and amended the monetary claim for usage profits to JPY 4,970,950 (calculated at JPY 400,000 per month from the day after service of the complaint until the actual return date of September 2, 1997). Y, in turn, filed a counterclaim demanding that X pay the JPY 3 million reimbursement price plus default interest from the day after Y returned the backhoe.

The appellate court partially ruled in favor of X on the main claim (awarding JPY 2,732,258 for usage profits, calculated at JPY 220,000 per month) and partially in favor of Y on the counterclaim (ordering X to pay JPY 3 million plus default interest from the day after service of the counterclaim). Y, still dissatisfied, appealed certain aspects to the Supreme Court, particularly the award of usage profits to X and the timing of the default interest on the reimbursement.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court partially overturned the appellate court's decision, ruling more favorably for Y.

- Possessor's Right to Use and Profit Until Reimbursement:

The Court held: "Where the victim or loser of stolen goods or lost property (hereinafter 'stolen goods, etc.') demands their recovery from the possessor, and the possessor can refuse delivery of the stolen goods, etc. under Article 194 of the Civil Code until reimbursement of the price they paid, it is appropriate to interpret that the possessor has the right to use and profit from (使用収益 - shiyō shūeki) the stolen goods, etc., until such reimbursement is tendered by the victim, etc."The rationale provided by the Court was twofold:Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that Y had the right to possess and use/profit from the backhoe until reimbursement of the price. Consequently, X's claim for usage profits (whether framed as unjust enrichment or tort damages), which was premised on Y having no such right, was unfounded. The appellate court's decision awarding usage profits to X, based on the idea that Y became a bad faith possessor from the time of X's lawsuit (under Article 189(2)), was an error in interpreting and applying the law.- Balancing Protection: Article 194 aims to balance the protection of the victim and the good faith purchaser by allowing recovery only upon reimbursement. If the victim chooses to recover the goods, the possessor's position would be excessively unstable if they had to return past usage profits, especially since if the victim abandons recovery, the possessor (who would then be confirmed as owner through immediate acquisition under Article 192, subject to the two-year recovery right under Article 193) would be entitled to all usage profits. Depriving the possessor of usage profits only when the victim chooses reimbursement would contradict the balancing purpose of Article 194.

- Equity Regarding Interest: The price to be reimbursed by the victim does not include interest. To balance this, allowing the possessor to retain usage profits is fair to both parties.

- Possessor's Right to Claim Reimbursement Even After Returning the Goods:

The Court then addressed Y's counterclaim for the JPY 3 million reimbursement. Given the sequence of events – Y initially refused delivery pending reimbursement, but then returned the backhoe during the appeal to mitigate accumulating liability for usage profits (as erroneously ordered by the lower court) and subsequently filed a counterclaim for reimbursement – the Court found that X, by accepting the returned backhoe, should be deemed to have chosen the option of recovering the item by agreeing to reimburse the price.

Under these circumstances, it was appropriate to hold that Y could still claim reimbursement of the price from X under Article 194, even after having returned the backhoe. The Court explicitly stated that a Daishin'in judgment from December 11, 1929 (Minshu Vol. 8, p. 923), should be modified to the extent it conflicted with this view (that prior judgment had suggested the right to reimbursement might be lost if the possessor voluntarily returned the goods without receiving payment, treating it more like a mere defense or lien). - Timing of Default on Reimbursement Obligation:

The obligation of the victim (X) to reimburse the price paid by the good faith purchaser (Y) is an obligation without a fixed due date. According to Article 412, paragraph 3 of the Civil Code, such an obligation becomes overdue (and thus default interest starts accruing) from the time the obligee (Y) demands performance from the obligor (X).

Considering the specific history of this case, the Supreme Court found that Y's demand for reimbursement of the price was effectively communicated to X at the time Y returned the backhoe to X.

Therefore, X's obligation to reimburse the JPY 3 million became overdue at the time X received the backhoe back from Y. Default interest (at the statutory rate of 5% per annum, as the counterclaim was for a civil, not commercial, debt in this context) should accrue from the day after Y returned the backhoe (September 3, 1997) until payment was complete. The appellate court had erred in ruling that the reimbursement obligation only became overdue from the day after service of Y's counterclaim.

Outcome: The Supreme Court reversed the appellate court's decision regarding X's claim for usage profits (dismissing X's claim entirely) and modified the part regarding Y's counterclaim for reimbursement to reflect that default interest on the JPY 3 million began from the day after Y returned the backhoe.

Analysis and Implications

This 2000 Supreme Court judgment significantly clarifies the rights of good faith purchasers of stolen goods under Article 194 of the Civil Code, particularly concerning their use of the goods and their ability to recover the purchase price.

- Right to Use and Profit Affirmed: The Court unequivocally affirmed that a good faith purchaser protected by Article 194 has the right to use and benefit from the stolen goods until the victim tenders reimbursement of the purchase price. This is a major clarification, as lower courts had sometimes held that the possessor becomes a "bad faith possessor" liable for usage profits from the date a recovery lawsuit is filed by the victim (under Article 189(2)). This ruling decouples the Article 194 possessor's right to use from the general rules on fruits from possession once a recovery suit is filed, emphasizing the unique balancing act of Article 194.

- Reimbursement Claim Survives Return of Goods (Under Specific Circumstances): The decision that the possessor can still claim reimbursement even after returning the goods (especially when done to mitigate erroneously imposed liability) is a practical and equitable one. It prevents the possessor from being forced to hold onto the goods indefinitely merely to preserve their reimbursement claim if the victim is slow to pay, particularly if the possessor faces accumulating (though, as per point 1, generally not awardable) claims for usage. It modifies prior, stricter case law. The key here was the Court's interpretation that the victim's acceptance of the returned goods, in the context of the ongoing litigation and the possessor's assertion of Article 194, amounted to the victim choosing the "recover and reimburse" option.

- Clarity on Default Timing for Reimbursement: Pinpointing the start of default interest on the reimbursement amount to the time of demand (which, in this case, was constructively found to be the time of the return of the goods under litigation) provides clearer guidance than linking it to the later filing of a counterclaim.

- Balancing Interests: The entire judgment is underpinned by an effort to achieve a fair balance between the victim of theft and the good faith purchaser, as intended by Article 194. Allowing the possessor to use the goods offsets the fact that they do not receive interest on the reimbursed price. Allowing them to claim reimbursement even after returning the goods under pressure prevents an unfair forfeiture of their statutory right.

- Practical Guidance for Similar Disputes: This case provides important practical guidance:

- Victims: If they want the stolen goods back from a protected good faith purchaser, they must be prepared to reimburse the price paid. They cannot claim usage profits for the period the possessor rightfully holds the item pending reimbursement.

- Good Faith Purchasers: They have a right to use the goods until reimbursed. If they return the goods before reimbursement, especially under litigation pressure, they should ensure their claim for reimbursement is clearly maintained.

This Supreme Court decision significantly strengthens the position of good faith purchasers under Article 194 by affirming their right to use the property pending reimbursement and securing their right to claim that reimbursement even if they return the item before payment under specific litigious circumstances. It emphasizes equity and the intended balance of protections within this specific provision of the Civil Code.