Sticking to the Script: Agency Reasons in Workers' Comp and the Scope of Court Review

Judgment Date: February 16, 1993

Case Number: Heisei 2 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 45 – Claim for Revocation of Workers' Compensation Non-Payment Decision

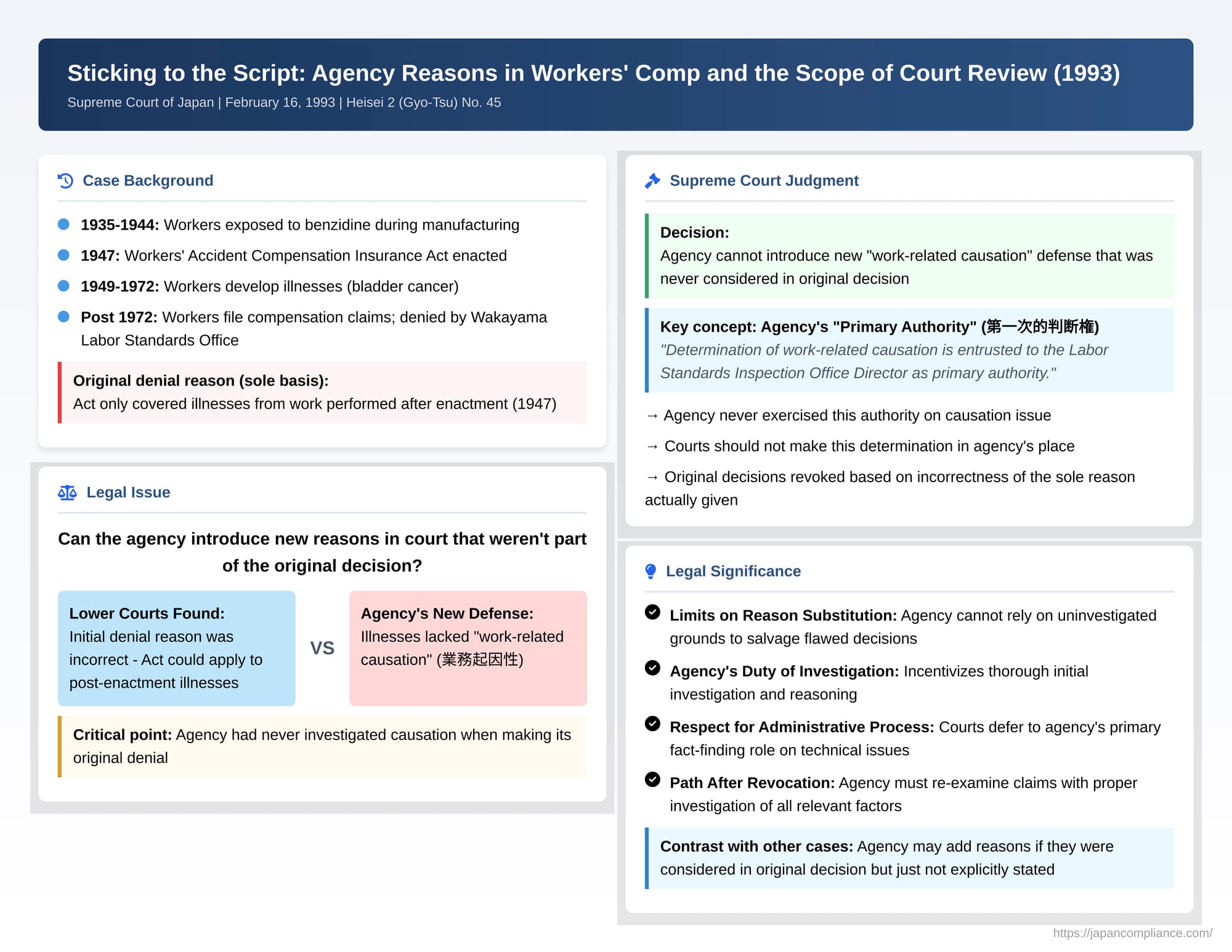

When a government agency denies a citizen's claim for benefits, it must provide reasons for that denial. This is a fundamental aspect of administrative fairness. But what happens if the agency, when challenged in court, tries to introduce new, previously unstated reasons to defend its original decision? A 1993 Japanese Supreme Court decision involving workers' compensation claims for illnesses linked to pre-war chemical exposure sheds light on the limits of such a strategy, particularly when the agency failed to investigate those new grounds initially.

The Benzidine Exposure Case: A Fight for Compensation

The case involved several workers (or their families, collectively "X and others") who had been engaged in benzidine manufacturing between 1935 and 1944. Years later, between 1949 and 1972, they developed serious illnesses, including bladder cancer, which they attributed to their workplace exposure. They subsequently filed claims for benefits under Japan's Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act (労災保険法 - Rōsai Hoken Hō). This Act was enacted in 1947, with its main provisions coming into force on September 1, 1947, after the workers' period of exposure.

The Director of the Wakayama Labor Standards Inspection Office (the Defendant, "Y") issued decisions denying these claims (不支給決定 - fushikyū kettei). The sole reason provided by Y for these denials was a legal interpretation: that the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act only covered injuries or illnesses resulting from work performed after the Act's enforcement date. Since the claimants' exposure to benzidine occurred before this date, Y concluded that their illnesses were not compensable under the Act.

X and others sued to revoke these non-payment decisions.

A New Defense in Court: The Agency's Shift

The lower courts (Wakayama District Court and Osaka High Court) first addressed the substantive legal issue raised by Y. They both concluded that Y's interpretation was incorrect: the Act could apply to illnesses that manifested after its enforcement, even if the causative work exposure occurred before the Act came into force. This was a significant victory for the claimants, establishing that the original reason for denial was unlawful.

However, during the litigation, Y attempted to introduce a new argument to defend the denials, at least concerning three of the affected workers. Y claimed that, for these individuals, their specific illnesses lacked the necessary "work-related causation" (業務起因性 - gyōmu kigensei) – meaning their conditions were not, in fact, caused by their employment, regardless of when the exposure occurred.

Both the District Court and the High Court refused to consider this new argument. They reasoned that the issue of work-related causation was not part of the original decision to deny benefits, and therefore, they would not examine it in the context of the current lawsuit. Y appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing, in part, that the lower courts had erred by not fully examining all relevant issues, including the newly raised point about work-relatedness.

The Supreme Court's Decision (February 16, 1993)

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions. The Court specifically affirmed the refusal to consider Y's new argument about work-related causation.

Why the New Reason Was Barred: Deference to the Agency's Primary Judgment Role

The Supreme Court's reasoning was clear:

- Agency's Initial Stance Was Unequivocal: The Court emphasized that it was evident from the record that Y had made its non-payment decisions solely and exclusively on the legal ground that the workers' exposure predated the enforcement of the Compensation Act. Y had not conducted any investigation into, nor made any judgment on, the factual question of whether the illnesses were actually caused by the benzidine exposure in their work.

- Agency's Primary Authority (第一次的判断権 - daiichiji-teki handan-ken): The determination of work-related causation for an illness or injury is a complex factual and often medical assessment. The law entrusts the Labor Standards Inspection Office Director with the primary authority and responsibility to investigate these matters and make an initial judgment. This is a specialized function.

- Court's Role When Agency Has Not Acted: Since Y had clearly not exercised its primary judgment authority on the issue of work-related causation when making the specific non-payment decisions being challenged, the Supreme Court held that the lower courts were correct in:

- Reserving their own finding or judgment on the work-relatedness issue. It was not for the courts to step into the agency's shoes and make this initial factual determination as a new defense for that particular set of denial decisions.

- Revoking the non-payment decisions based on the illegality of the sole reason originally given by Y (i.e., the incorrect legal interpretation that the Act did not apply).

The Supreme Court found no error in this approach by the lower courts.

Implications of the Ruling

This decision has important implications for how administrative agencies conduct themselves and how courts review their decisions:

- Limits on "Substitution/Addition of Reasons": While agencies sometimes can introduce new reasons in court to defend a challenged disposition, this case demonstrates a significant limitation. If the agency's original decision was based on a specific, narrow ground, and it failed to investigate or consider other potential grounds at that time, it may be barred from raising those uninvestigated grounds later in court to save the original decision.

- Importance of Thorough Initial Agency Investigation: The ruling incentivizes administrative agencies to conduct comprehensive investigations and articulate all relevant grounds for their decisions from the outset. An agency cannot simply rely on one potentially weak legal argument and expect to introduce entirely new, uninvestigated factual defenses if that initial argument fails in court.

- Respect for the Administrative Process and Agency Expertise: The decision underscores respect for the administrative agency's role as the primary fact-finder and decision-maker on technical issues falling within its statutory competence. If the agency abdicates or bypasses that role concerning a particular essential element of a claim (like work-related causation here), it cannot necessarily expect the court to perform that initial assessment for it to justify the original flawed decision.

- The Path After Revocation: The revocation of Y's non-payment decisions did not automatically mean the claims would be paid. Instead, it meant that the original, legally flawed decisions were nullified. The agency (Y) would then be obligated, under the binding effect of the court's judgment, to re-examine the claims. At this stage of re-examination, Y could and should properly investigate the work-related causation for each claimant. If, after such investigation, Y were to deny a claim based on a finding of no work-related causation, that would constitute a new administrative decision, which would then be subject to its own potential administrative and judicial review.

Broader Context and Comparisons

This case is often discussed in the context of the general rules about an agency "substituting or adding reasons" (理由の追加・差替え - riyū no tsuika/sashikae) in court. While the general principle often allows an agency some flexibility (provided the core identity of the administrative action is not changed and procedural guarantees like those from a hearing are not violated), this judgment highlights a key constraint tied to the agency's exercise of its primary decision-making authority (第一次的判断権 - daiichiji-teki handan-ken).

The core issue here was not just that the reason was new, but that it related to a fundamental factual inquiry (work-relatedness) that the agency had completely failed to undertake when making the original decision. This distinguishes it from cases where an agency might merely reframe or add detail to a line of reasoning it had already considered, or where the new reason is closely related to the original one and doesn't require entirely new factual investigations that were the agency's initial duty.

In today's legal landscape, such a case might also involve an "obligation-to-act lawsuit" (義務付け訴訟 - gimuzuke soshō), where plaintiffs not only seek revocation of the denial but also an order compelling the agency to grant the benefits. Even in such cases, courts retain discretion to simply revoke a flawed decision and remand it for further agency action if that is deemed more conducive to a swift and proper resolution, especially when complex factual investigations are needed. The principles from this 1993 Supreme Court ruling would likely inform how a court exercises that discretion, emphasizing the agency's responsibility to conduct a full and proper initial assessment.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court’s 1993 decision in this workers' compensation case serves as a crucial reminder that administrative agencies must diligently exercise their primary fact-finding and decision-making responsibilities at the initial stage of considering a claim or application. If an agency issues a denial based on a specific, narrow, and ultimately unlawful ground, without having investigated other potentially relevant factual elements, it risks being precluded from later introducing those unexamined factors in court to salvage its flawed original decision. This approach upholds the integrity of the administrative decision-making process and ensures that matters requiring initial agency investigation and expertise are, indeed, first addressed by the agency before a court is asked to rule on them.