Japan’s Overseas Anti-Corruption Stance: Compliance Roadmap for US Companies Operating Abroad

TL;DR

- Japan criminalises overseas bribery of foreign public officials under the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA) and expects global groups to prevent misconduct.

- Enforcement is rising: coordinated investigations with US DOJ、SEC and other OECD peers have increased since 2020.

- US parent companies must integrate Japanese subsidiary risks into FCPA programmes, reinforce whistle-blower systems and document third-party due diligence.

Table of Contents

- The International Context: OECD and UNCAC

- Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA): Article 18

- OECD Pressure and the 2023 UCPA Amendments

- The METI Guidelines (外国公務員贈賄防止指針)

- Comparison with FCPA and UK Bribery Act

- Compliance Imperatives for US Businesses

- Conclusion

As globalization intertwines economies, the fight against corruption, particularly bribery involving foreign public officials, has become a critical compliance area for multinational corporations. While the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) and the UK Bribery Act often dominate discussions among American businesses, understanding the specific regulations of other major economies where they operate, such as Japan, is equally vital. Japan, a signatory to key international anti-corruption conventions, enforces its own robust framework primarily through its Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA), which has seen significant amendments recently, increasing risks and compliance burdens for companies with Japanese connections.

This article delves into Japan's legal regime against foreign bribery, focusing on the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (不正競争防止法 - fusei kyōsō bōshi hō), its recent changes effective from April 2024, and its implications for US companies operating in or doing business related to Japan.

The International Context: OECD and UNCAC

Japan's efforts against foreign bribery are rooted in its international commitments. Two primary conventions underpin the global anti-corruption architecture:

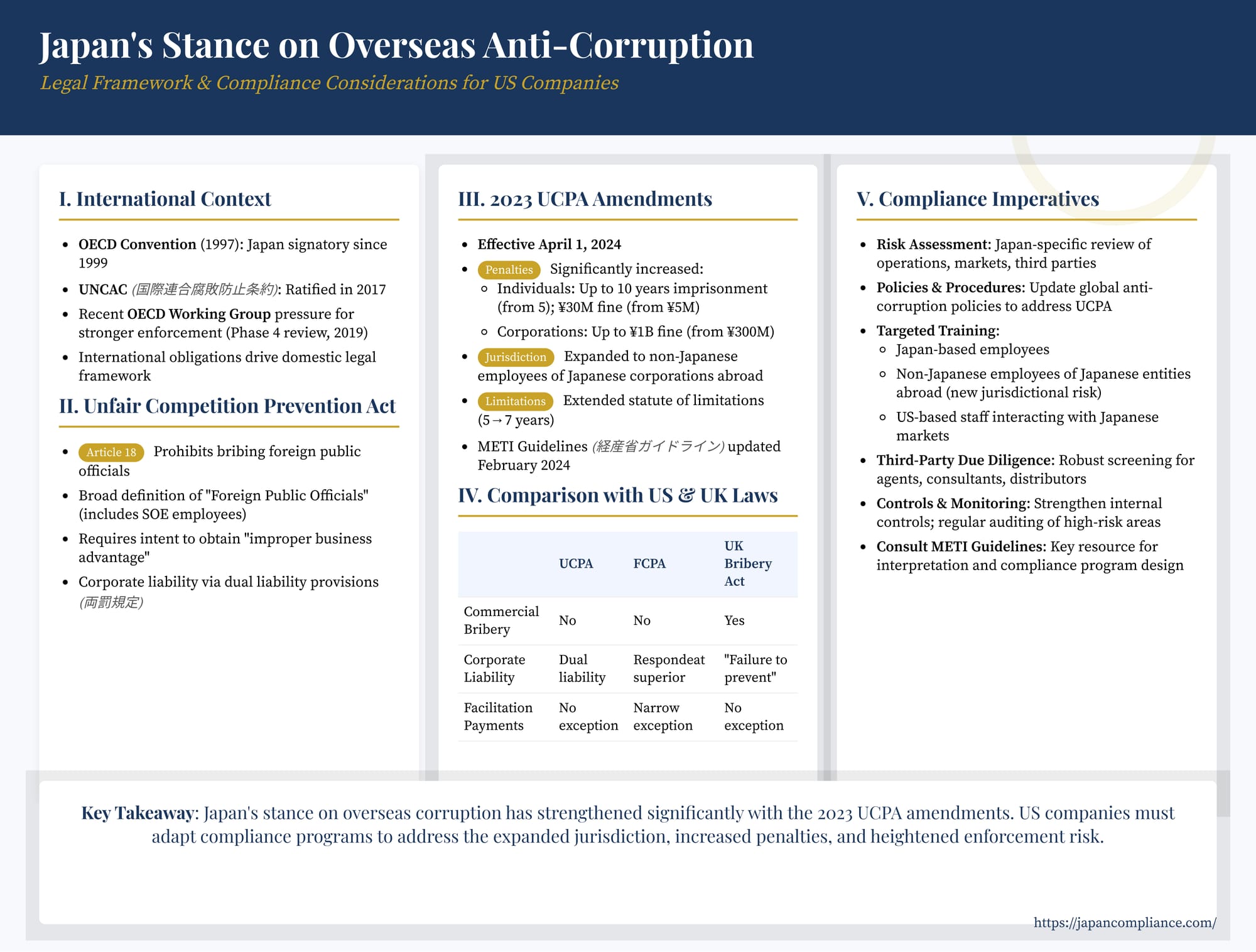

- OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions (OECD外国公務員贈賄防止条約): Adopted in 1997 and effective since 1999, this convention obligates signatory states (including Japan, the US, and the UK) to criminalize the bribery of foreign public officials to obtain or retain international business. A key feature is the peer-review monitoring mechanism conducted by the OECD Working Group on Bribery, which assesses member countries' implementation and enforcement, often leading to recommendations for legislative or practical improvements.

- United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC / 国連腐敗防止条約): Effective since 2005, UNCAC is a broader instrument covering not only foreign bribery but also domestic corruption, embezzlement, trading in influence, illicit enrichment, and money laundering. It emphasizes preventive measures, criminalization, international cooperation, and asset recovery. Japan ratified UNCAC relatively recently, in 2017, further solidifying its commitment to international anti-corruption standards.

These conventions mandate that signatory states establish legal frameworks to prosecute bribery involving foreign officials, contributing to a more level playing field in international commerce.

Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA): Article 18

Japan implemented its obligations under the OECD Convention primarily by amending the UCPA in 1998 to introduce Article 18, which specifically prohibits the bribery of foreign public officials. This article has been the cornerstone of Japan's foreign anti-bribery enforcement.

Core Prohibition:

UCPA Article 18, paragraph 1 states that "No person shall give, offer or promise any money or other benefit to a foreign public official, etc., in order to obtain an improper business advantage concerning international commercial transactions, for the purpose of having the foreign public official, etc. act or refrain from acting in relation to his/her duties, or having the foreign public official, etc. use his/her position to influence another foreign public official, etc. to act or refrain from acting in relation to that official's duties."

Let's break down the key elements:

- Who is Prohibited ("Any Person" - 何人も): The prohibition applies broadly to individuals (Japanese or foreign nationals) and legal entities (法人 - hōjin). While individuals are directly liable, corporations face punishment under dual liability provisions (ryōbatsu kitei - 両罰規定) when their representatives, agents, or employees commit the offense in relation to the corporation's business.

- Who is a "Foreign Public Official, etc." (外国公務員等): The definition is comprehensive and was clarified in a 2001 amendment. It includes:

- Those engaged in public service for a foreign national or local government.

- Those engaged in duties for an entity established under foreign special law to carry out specific administrative affairs (e.g., certain government agencies).

- Employees of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) or similar entities where foreign governments hold significant control (ownership/voting rights exceeding 50%, special privileges). The inclusion of SOE employees is a critical point often requiring careful assessment in practice.

- Those engaged in public service for a public international organization (constituted by governments or other IOs).

- Those exercising public functions delegated by a foreign government or public international organization.

- What Constitutes a Bribe ("Money or other benefit" - 金銭その他の利益): This is interpreted broadly to include not only cash payments but also gifts, entertainment, travel expenses, donations, loans, providing employment to relatives, or any other tangible or intangible advantage.

- The Quid Pro Quo (Purpose): The bribe must be offered with the intent to induce the official to "act or refrain from acting" in their official capacity or to use their influence on another official.

- The Business Purpose ("Improper business advantage" - 営業上の不正の利益): The bribe must be intended to obtain or retain business or secure any other improper advantage in the conduct of international commercial transactions. This covers a wide range of scenarios, from winning contracts to obtaining permits or reducing tax liabilities.

Extraterritorial Jurisdiction:

Japan's UCPA asserts jurisdiction in several ways:

- If any part of the bribery act occurs within Japan.

- If the act is committed outside Japan by a Japanese national (citizenship principle).

- Crucially, following the 2023 amendments (effective April 1, 2024), jurisdiction now extends to acts committed outside Japan by non-Japanese nationals who are representatives, agents, or employees of a Japanese corporation (specifically, a legal entity having its principal office in Japan) when acting in relation to that corporation's business. This significantly expands the potential liability for foreign employees working for Japanese subsidiaries or branches abroad.

Corporate Liability (Dual Liability Provisions):

As mentioned, UCPA Article 22 provides that if a representative, agent, employee, or other worker of a corporation commits an Article 18 violation in connection with the corporation's business, the corporation itself can be punished with a fine, in addition to the punishment imposed on the individual offender. This underscores the importance of corporate compliance programs.

OECD Pressure and the 2023 UCPA Amendments

The most recent amendments to the UCPA, effective April 1, 2024, were largely driven by recommendations from the OECD Working Group on Bribery's Phase 4 evaluation of Japan, published in 2019. The OECD report, while acknowledging Japan's efforts, highlighted areas for improvement, particularly concerning the perceived leniency of sanctions and jurisdictional gaps. The 2023 amendments directly addressed these concerns:

- Increased Penalties: Sanctions were significantly enhanced to align better with international standards and provide a stronger deterrent.

- Individuals: Maximum imprisonment increased from 5 years to 10 years; maximum fine increased from ¥5 million to ¥30 million (or both).

- Corporations: Maximum fine under the dual liability provision increased substantially from ¥300 million to ¥1 billion.

- Expanded Extraterritoriality: As detailed above, the law now explicitly covers non-Japanese employees/agents acting abroad for Japanese companies headquartered in Japan, closing a previously identified jurisdictional gap.

- Extended Statute of Limitations: The limitation period for prosecuting foreign bribery offenses was extended from 5 years to 7 years, allowing more time for complex international investigations.

These amendments signal Japan's renewed commitment to tackling foreign bribery and responding to international scrutiny. They raise the stakes significantly for both individuals and corporations involved with Japanese business entities.

The METI Guidelines (外国公務員贈賄防止指針)

To aid businesses in understanding and complying with the UCPA, Japan's Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) publishes the "Guidelines for Preventing Bribery of Foreign Public Officials." These guidelines, while not legally binding law, provide crucial interpretations and practical advice. They have been periodically updated, with the latest revision in February 2024 reflecting the 2023 UCPA amendments.

Key aspects addressed by the METI Guidelines include:

- Clarifications on the scope of "foreign public official," "improper business advantage," and "international commercial transactions."

- Discussion on corporate liability, including factors considered when assessing a parent company's responsibility for acts committed by employees of subsidiaries or by third-party agents (e.g., degree of control, supervision).

- Guidance on establishing effective internal compliance programs, emphasizing risk assessment, policies, training, due diligence, and monitoring.

- Examples of high-risk scenarios and red flags.

- Discussion on acceptable small gifts or hospitality (though caution is advised as there's no explicit de minimis exception).

US companies should consult the latest version of these METI guidelines (available in English on METI's website) as part of their compliance efforts in Japan.

Comparison with FCPA and UK Bribery Act

For US companies, understanding how Japan's UCPA compares to the more familiar FCPA and the stringent UK Bribery Act 2010 is essential.

- Scope of Prohibited Payments: All three laws broadly prohibit bribing foreign public officials. However, the UK Bribery Act also criminalizes commercial (private-to-private) bribery and the receipt of bribes, which are generally outside the scope of the FCPA's anti-bribery provisions and UCPA Article 18.

- Corporate Liability:

- FCPA: Corporations are liable under respondeat superior principles for acts of employees/agents.

- UCPA: Uses the ryōbatsu kitei (dual liability) system. Parent liability for subsidiary actions often depends on demonstrating sufficient control or involvement, as discussed in METI guidelines.

- UK Bribery Act: Includes the unique Section 7 offense of a "failure of commercial organisations to prevent bribery" by associated persons (employees, agents, subsidiaries, etc.). The only defense is having "adequate procedures" in place. This creates a stricter form of corporate liability.

- Extraterritoriality: All three have significant extraterritorial reach. FCPA applies to US issuers, domestic concerns, and acts with a US nexus. UK Bribery Act applies to UK companies/citizens/residents worldwide and to non-UK companies that carry on a part of their business in the UK. UCPA applies to acts in Japan, acts by Japanese nationals abroad, and now acts by foreign employees/agents acting for Japanese entities abroad. The overlap means multinational companies can face prosecution under multiple laws for the same conduct.

- Facilitation Payments: The FCPA historically had a narrow exception for small payments made to expedite routine governmental actions, though this exception is highly disfavored and effectively eliminated by DOJ/SEC policy. The UK Bribery Act has no such exception. The UCPA also lacks an explicit exception for facilitation payments, and the METI guidelines generally advise against them.

- Accounting Provisions: The FCPA uniquely includes explicit books-and-records and internal controls provisions, requiring issuers to maintain accurate financial records and adequate internal accounting controls. While Japan and the UK have general accounting and corporate governance laws, their anti-bribery statutes do not contain equivalent specific provisions.

- Enforcement and Resolutions: The US (DOJ/SEC) and UK (SFO) are known for aggressive enforcement, often utilizing Deferred Prosecution Agreements (DPAs) or Non-Prosecution Agreements (NPAs). Japan's enforcement of foreign bribery cases has historically been less frequent, although the recent amendments and OECD pressure may signal increased activity. Japan does not currently have a formal DPA/NPA system for corporate resolutions, though cooperation can be a mitigating factor in sentencing.

Compliance Imperatives for US Businesses

Given Japan's clear legal prohibitions, expanded jurisdiction, increased penalties, and international commitments, US companies with any nexus to Japan must ensure their global compliance programs adequately address UCPA risks. Key steps include:

- Tailored Risk Assessment: Conduct thorough risk assessments specific to Japanese operations, markets, and third-party relationships (including subsidiaries, JVs, agents, distributors). Pay particular attention to interactions with entities that might qualify as SOEs or involve delegated public functions.

- Clear Policies and Procedures: Ensure global anti-corruption policies explicitly address UCPA requirements, including the broad definition of foreign officials and the lack of a facilitation payment exception. Translate key policies into Japanese for local staff.

- Targeted Training: Provide regular, tailored training to all relevant personnel, including:

- Employees based in Japan.

- Employees of Japanese subsidiaries (regardless of nationality).

- US-based employees interacting with Japanese markets or officials.

- Critically, non-Japanese employees working outside Japan for a Japanese subsidiary or branch, given the new extraterritorial reach.

- Robust Third-Party Due Diligence: Implement risk-based due diligence procedures for agents, consultants, distributors, JV partners, and other intermediaries operating in or connected to Japan. Document the diligence process thoroughly.

- Effective Internal Controls: Strengthen financial and accounting controls to detect and prevent illicit payments. Ensure appropriate approval processes for expenditures involving foreign officials or high-risk third parties.

- Accessible Reporting Mechanisms: Maintain confidential and accessible channels for employees and third parties to report concerns or potential violations without fear of retaliation.

- Monitoring and Auditing: Regularly monitor and audit compliance efforts, particularly in high-risk areas or operations connected to Japan.

- Consult METI Guidelines: Use the official METI Guidelines as a key resource for interpreting UCPA provisions and designing compliance measures.

Conclusion

Japan stands firmly alongside the US, UK, and other OECD nations in prohibiting the bribery of foreign public officials. The Unfair Competition Prevention Act, particularly after its 2023 amendments, imposes significant obligations and potential liabilities, including substantial fines and imprisonment, on both individuals and corporations. The expansion of extraterritorial jurisdiction to cover foreign employees of Japanese entities underscores the need for vigilance. US companies cannot afford to overlook UCPA compliance; it must be an integral part of any effective global anti-corruption program, requiring tailored risk assessments, specific policies, targeted training, and robust controls to navigate the complexities of doing business responsibly in and with Japan.

- AI-Generated Copyright Infringement in Japan: Liability for Users, Developers & Platforms Explained

- International Tax Risks in Japan: PE, Transfer Pricing, CFC & Pillar Two Guide for US Companies

- Director Liability and Corporate Donations in Japan: Balancing Philanthropy and Fiduciary Duty

- METI – “Guidelines for the Prevention of Bribery of Foreign Public Officials” (English PDF)

- MOJ – OECD Anti-Bribery Convention Implementation Report (2024)