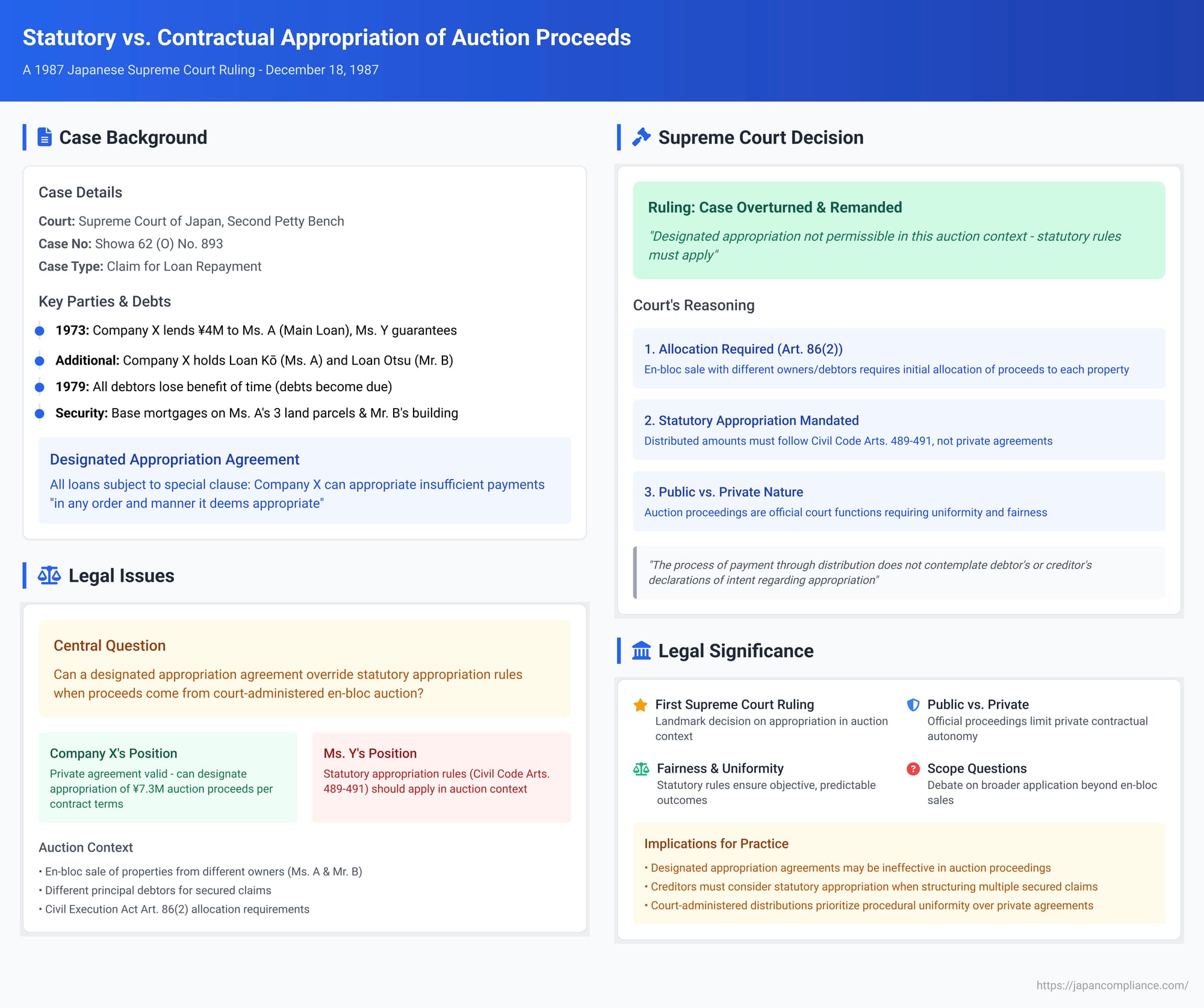

Statutory vs. Contractual Appropriation of Auction Proceeds: A 1987 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Case Name: Claim for Loan Repayment

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Number: Showa 62 (O) No. 893

Date of Judgment: December 18, 1987

This article delves into a significant Japanese Supreme Court judgment from December 18, 1987. The case addresses a critical issue at the intersection of private agreements and public execution proceedings: when proceeds from a real estate auction are insufficient to cover multiple debts owed to a single creditor, can a prior agreement allowing the creditor to choose how the funds are applied (a "designated appropriation agreement") override the statutory rules of payment appropriation? This is particularly complex when the auction involves an "en-bloc sale" of properties belonging to different owners securing debts of different principal debtors.

Factual Background: A Complex Web of Debts and Securities

The facts of the case, simplified for clarity, are as follows:

- The Main Loan and Guarantee:

- On June 12, 1973, Company X (the plaintiff creditor, appellee in the Supreme Court) lent JPY 4 million to Ms. A (the principal debtor). This debt, including principal, interest, and damages, is referred to as the "Main Loan."

- Ms. Y (the defendant guarantor, appellant in the Supreme Court) entered into a joint guarantee agreement with Company X for Ms. A's Main Loan.

- On December 9, 1979, both Ms. A (for the Main Loan) and Ms. Y (for her guarantee obligation) lost the "benefit of time" (i.e., their debts became immediately due).

- Other Loans:

- Company X also held another loan claim against Ms. A ("Loan Kō").

- Additionally, Company X had a loan claim against Mr. B ("Loan Otsu").

- Ms. A and Mr. B also lost the benefit of time for Loan Kō and Loan Otsu, respectively, on December 9, 1979.

- Designated Appropriation Agreement: All three loans (Main Loan, Loan Kō, and Loan Otsu) were subject to a special agreement stipulating that if any payment received was insufficient to extinguish the entire debt amount (including principal, interest, and damages), Company X could appropriate the funds in any order and manner it deemed appropriate. This is known as a "designated appropriation agreement" (shitei jūtō no tokuyaku).

- Mortgage Security:

- Company X held base mortgages (neteitōken) on three parcels of land owned by Ms. A (with a combined credit limit of JPY 5 million) and on one building owned by Mr. B (with a credit limit of JPY 10 million).

- These mortgages secured the Main Loan, Loan Kō, and Loan Otsu. The judgment noted that the specific allocation of which mortgage secured which individual debt was not entirely clear.

- En-Bloc Auction and Distribution:

- The three land parcels owned by Ms. A and the building owned by Mr. B were sold together in a real estate auction (an "en-bloc sale" or ikkatsu baikyaku, similar to current secured real property auctions).

- From this auction, Company X received a distribution of JPY 7,296,172.

- Lawsuit and Creditor's Appropriation:

- Company X subsequently sued Ms. Y (the guarantor) in the Miyazaki District Court (Nobeoka Branch) for approximately JPY 2.34 million remaining on her guarantee obligation for the Main Loan.

- During the trial, Company X declared its intention to apply the JPY 7,296,172 auction proceeds according to the designated appropriation agreement. It argued that after this designated appropriation, the outstanding amount on the Main Loan (principal and damages) was the claimed JPY 2.34 million.

The Legal Dispute: Designated Appropriation vs. Statutory Rules in Auctions

The central legal question was whether Company X could validly apply the auction proceeds according to its private "designated appropriation agreement" when those proceeds came from a court-administered en-bloc auction involving properties of different owners securing debts of different principal debtors. Alternatively, should the application of proceeds follow the statutory rules of appropriation laid down in the Civil Code (statutory appropriation or hōtei jūtō)?

Typically, under Japanese law (Civil Code Art. 488), parties can agree on how payments are to be appropriated. In the absence of such agreement, the debtor, then the creditor, can designate at the time of payment. If no designation is made, statutory rules (Civil Code Arts. 489-491) apply, prioritizing, for example, due debts, debts most beneficial for the debtor to discharge, and then pro-rata application. This case tested the limits of private agreements in the context of public execution.

Lower Courts' Position

Both the Miyazaki District Court (Nobeoka Branch) (first instance) and the Fukuoka High Court (Miyazaki Branch) (appellate court) sided with Company X. They upheld the validity of the designated appropriation, thereby accepting Company X's calculation of the remaining debt owed by Ms. Y. Ms. Y appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling

On December 18, 1987, the Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Supreme Court held that, in this specific auction context, Company X's designated appropriation was not permissible, and the proceeds should have been applied according to statutory rules.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Allocation of Proceeds in En-Bloc Sales (Civil Execution Act Art. 86(2)):

When multiple properties are sold en-bloc in an auction (as permitted by Civil Execution Act Art. 61, via Art. 188 for secured property auctions), and these properties have different owners, and either the mortgagees are different or (as in this case) the mortgagee is the same but the principal debtors for the secured claims are different, then it is a situation where "it is necessary to determine the amount of the sales proceeds for each property" (as per Civil Execution Act Art. 86(2), applicable via Art. 188).

In such cases, the proceeds from the en-bloc sale must first be notionally allocated to each individual property (e.g., pro-rata based on their respective minimum sale prices or, under current law, standard sales values). The burden of execution costs for each property must also be determined. Only then can the amount distributable to the secured creditor from each property's allocated proceeds be calculated. - Statutory Appropriation Takes Precedence:

If the total amount distributed to a single secured creditor from these allocated proceeds is insufficient to satisfy all the secured claims that creditor holds against the respective debtors, the distributed sum must be appropriated according to the statutory rules of appropriation found in Articles 489 to 491 of the Civil Code.

A pre-existing agreement allowing the creditor to designate the appropriation order (like Company X's agreement) is not permissible in this context. - Rationale for Disallowing Designated Appropriation in Auctions:

- Official Nature of Execution Proceedings: Real estate auction proceedings are conducted by an official execution body (the court) exercising its public duties. The process of payment through distribution does not contemplate or provide a mechanism for the debtor's or creditor's declarations of intent regarding appropriation to be formally incorporated at that stage.

- Fairness and Uniformity: When a single creditor receives a distribution for multiple claims, applying the statutory rules of appropriation—which are designed to be objectively fair and reasonable—is most consistent with the nature and objectives of the auction system. This ensures uniformity and predictability.

The Supreme Court concluded that the lower courts erred in upholding Company X's designated appropriation without first requiring an allocation of the en-bloc sale proceeds to the respective properties of Ms. A and Mr. B, and then applying those allocated amounts according to statutory rules.

Analysis and Significance

This 1987 Supreme Court judgment was a landmark decision, being the first by the highest court to directly address how auction proceeds should be appropriated to multiple debts in the presence of a designated appropriation agreement. Its implications remain significant.

- The "En-Bloc Sale" Context: The specific facts involved an en-bloc sale of properties belonging to different owners, securing debts of different principal debtors. This triggered Article 86(2) of the Civil Execution Act, requiring an initial allocation of proceeds. The Supreme Court's reasoning is explicitly tied to this scenario.

- Public Nature of Execution vs. Private Autonomy: The ruling underscores a fundamental principle: the public and official nature of court-administered execution proceedings can limit the scope of private autonomy (freedom of contract). While designated appropriation agreements are generally valid between parties, their application is restricted when payments are made through the formal, regulated process of auction distribution. The Court prioritized the uniformity, fairness, and procedural integrity of the execution system.

- Scope of the Ruling – "In This Case": Legal commentators have debated the precise scope of "in this case" (kono baai) in the judgment.

- A narrow interpretation might limit the ruling strictly to en-bloc sales where Article 86(2) allocation is mandatory.

- However, many scholars argue for a broader interpretation. The Supreme Court's emphasis on the "auction system's nature" and the call for "uniformity" and "fairness" via statutory appropriation suggests that the principle might extend to other auction scenarios where a creditor receives a single sum for multiple debts, even if it's from a single property or multiple properties of the same owner (where Art. 86(2) allocation isn't strictly required for different owners/debtors). The underlying logic seems to be that once money enters the court-managed distribution process, its application should follow objective, statutory rules to avoid complexities and ensure fairness to all parties involved (including other creditors or the debtor(s)).

- Rationale for Requiring Appropriation at Distribution: The judgment implies that appropriation must occur at the point of receiving the auction distribution. This is partly linked, by some commentators, to procedural rules like Article 62(3) of the Rules of Civil Execution (then applicable), which required court clerks to endorse on the original title of obligation the amount satisfied by the distribution. To make such an endorsement for each of several debts, the distributed sum must first be appropriated.

However, critics point out that:- This rule's main purpose is to prevent double recovery using the same title of obligation in subsequent executions, not to dictate substantive appropriation rules.

- The rule's effectiveness is limited (e.g., if multiple originals of the title exist or it's lost).

- Crucially, for secured creditors receiving distribution in a real estate auction, this specific rule requiring endorsement on the title of obligation was not directly applicable (due to then Rule 173(1)(ii)). This weakens it as a primary justification for overriding designated appropriation agreements for secured creditors in real estate auctions, which was the core scenario of this case.

- The more fundamental critique is whether procedural rules (especially those made by the Supreme Court as Rules, not by the Diet as Law) should override substantive Civil Code principles like freedom of contract for appropriation, without more explicit legislative direction.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1987 decision established a crucial principle: in the context of proceeds from a real estate auction, particularly complex en-bloc sales involving different owners and debtors, statutory rules of appropriation will prevail over private agreements allowing creditor designation. The Court prioritized the official, uniform, and fair administration of execution proceedings. This ruling has lasting implications for creditors holding multiple claims secured by various properties, emphasizing that reliance on private appropriation clauses may be ineffective once enforcement moves into the public auction arena. Creditors and their counsel need to be aware that auction proceeds will likely be applied based on statutory rules, impacting the satisfaction levels of different debts and potentially affecting claims against guarantors or for remaining deficiencies.