Statutory Superficies in Japan: Which Mortgage's Creation Date is Key When Multiple Mortgages Exist?

Date of Judgment: July 6, 2007

Case Name: Action for Removal of Building and Vacant Possession of Land

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

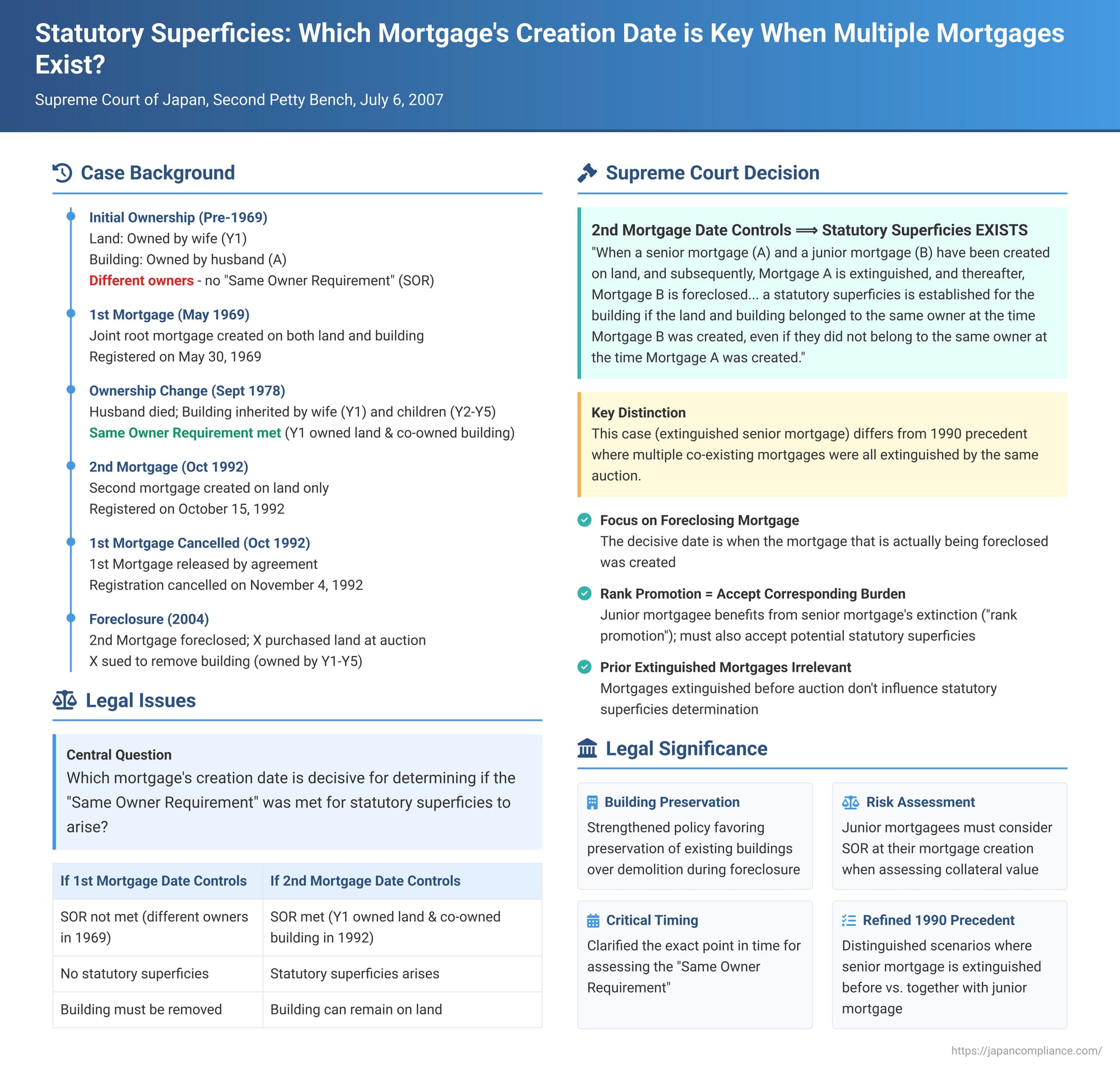

In Japanese property law, a "statutory superficies" (hōtei chijōken), established by Article 388 of the Civil Code, is a crucial concept designed to prevent the demolition of a building when the land it sits on is sold at a mortgage foreclosure auction, separating the ownership of the land from the ownership of the building. A key condition for the creation of this statutory right for the building owner to use the land is that the land and the building must have belonged to the same owner at the time the mortgage was created. But what happens when multiple mortgages are placed on the land at different times, and the "same-owner requirement" (SOR) was met for some but not others? And critically, what if a senior mortgage, created when the SOR was not met, is extinguished before a junior mortgage (created when the SOR was met) is foreclosed? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this complex interplay in a significant judgment on July 6, 2007.

The Complex Facts: Shifting Ownership and Layered Mortgages

The case involved a piece of land ("the Land") and a building ("the Building") constructed on it, with a history of changing ownership and multiple mortgages:

- Initial State: Y1 owned the Land. Her husband, A, owned the Building. Thus, at this stage, the Land and the Building were owned by different individuals.

- The 1st Mortgage: On May 29, 1969, a joint root mortgage (the "1st Mortgage") was created over both the Land (owned by Y1) and the Building (owned by A). This mortgage named A as the debtor and B as the root mortgagee. It was registered on May 30, 1969. At the time this 1st Mortgage was created, the Land and Building did not belong to the same owner in the simplest sense, although they were owned by a husband and wife.

- Change in Building Ownership: On September 26, 1978, A passed away. His wife, Y1 (who already owned the Land solely), and their children, Y2-Y5, inherited the Building, becoming its co-owners. Following this, Y1 was the sole owner of the Land and a co-owner (with her children Y2-Y5) of the Building. Under Japanese case law (specifically, Supreme Court, December 21, 1972, Minshū Vol. 25, No. 9, p. 1610, the "M90 case"), this situation – where the land is solely owned by an individual who is also a co-owner of the building on it – does satisfy the "same-owner requirement" for the purpose of statutory superficies.

- The 2nd Mortgage: On October 12, 1992, a second root mortgage (the "2nd Mortgage") was created. This mortgage was placed only on the Land (owned by Y1). It named an individual, C, as the debtor and D as the root mortgagee. This 2nd Mortgage was registered on October 15, 1992. Crucially, at the moment this 2nd Mortgage was established, the "same-owner requirement" (as per the M90 case precedent) was fulfilled because Y1 owned the Land and was a co-owner of the Building.

- Cancellation of the 1st Mortgage: On October 30, 1992, shortly after the 2nd Mortgage was created, the 1st Mortgage (held by B, which had encumbered both Land and Building) was cancelled by a mutual agreement of release (kaijo). The mortgage registration was formally cancelled on November 4, 1992.

- Foreclosure of the 2nd Mortgage: Subsequently, D, the holder of the 2nd Mortgage on the Land, initiated foreclosure proceedings.

- Auction Purchase: On July 2, 2004, X purchased the Land at the ensuing foreclosure auction. The ownership of the Building remained with Y1 and her children (Ys).

- The Lawsuit: X, as the new owner of the Land, sued Ys, demanding that they remove the Building and vacate the Land. Ys defended this claim by asserting that a statutory superficies had arisen in favor of the Building, allowing it to remain on the Land.

The Legal Conundrum: Which Mortgage Defines the "Same-Owner Requirement" Moment?

The central legal question was: which mortgage's creation date should be used as the reference point for determining if the "same-owner requirement" was met for a statutory superficies to arise?

- If the creation date of the 1st Mortgage was decisive, then the SOR was arguably not met (as Land and Building were owned by Y1 and A respectively, not a single entity or in a manner clearly satisfying the SOR before later precedents like M90 clarified co-ownership scenarios).

- If the creation date of the 2nd Mortgage (the one actually foreclosed) was decisive, then the SOR was met (Y1 owned Land and co-owned Building).

The District Court and the High Court both ruled against Ys, denying the existence of a statutory superficies. They relied on a 1990 Supreme Court precedent (Supreme Court, January 22, 1990, Minshū Vol. 44, No. 1, p. 314). This 1990 case held that if, at the time the first-ranking mortgage was created, the land and building were owned by different persons, a statutory superficies does not arise, even if they come under common ownership by the time a junior mortgage (which is ultimately foreclosed) is created, provided that first-ranking mortgage is also extinguished by the auction. The lower courts in the present case extended this logic, reasoning that even if the 1st Mortgage was cancelled by agreement before the foreclosure of the 2nd Mortgage, its initial "taint" (SOR not met at its creation) should prevent a statutory superficies from arising. Ys appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (July 6, 2007): Focus on the Senior-Most Foreclosing Mortgage

The Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' decisions and ruled in favor of Ys, holding that a statutory superficies had indeed arisen for the Building.

- The Guiding Principle: The Court established a clear principle for such situations: "When a senior mortgage (Mortgage A) and a junior mortgage (Mortgage B) have been created on land, and subsequently, Mortgage A is extinguished (e.g., by contractual release), and thereafter, Mortgage B is foreclosed, resulting in the land and the building upon it coming to be owned by different persons, a statutory superficies is established for the building if the land and building belonged to the same owner (in the sense required by law) at the time Mortgage B was created, even if they did not belong to the same owner at the time Mortgage A was created."

- Rationale for the Decision:

- Expectations of the Junior Mortgagee (D): The Court acknowledged that when D (the 2nd mortgagee) took its mortgage, it might have anticipated that if the 1st Mortgage (to B) remained in place and was foreclosed, no statutory superficies would arise (due to the 1990 precedent, as SOR was not met when the 1st Mortgage was created).

- Foreseeability of Senior Mortgage Extinguishment: However, the Supreme Court emphasized that mortgages are, by their nature, temporary security interests that can be extinguished for various reasons (e.g., repayment of the secured debt, release by the mortgagee, contractual cancellation) before any foreclosure. A junior mortgagee, when taking their security, should be aware of this possibility and factor it into their risk assessment and valuation of the collateral.

- Balancing Benefits and Burdens for Junior Mortgagee: When a senior mortgage is extinguished, the junior mortgagee benefits from "rank promotion" – their mortgage moves up in priority. They should, therefore, also accept the corresponding possibility that if the SOR was met at the time their own (now senior-most) mortgage was created, a statutory superficies might arise upon their foreclosure. Allowing a statutory superficies in such circumstances does not inflict an unforeseen loss on the junior mortgagee who should have considered this eventuality.

- Irrelevance of the Extinguished Senior Mortgagee's Interests: Since the 1st Mortgage was already extinguished before the foreclosure auction of the 2nd Mortgage, there is no need to consider or protect the expectations or interests of the former 1st mortgagee (B) when determining whether a statutory superficies arises from the 2nd mortgagee's (D's) foreclosure.

- Interpreting Civil Code Article 388: The "same-owner requirement" stipulated in Article 388 of the Civil Code should be judged based on the circumstances existing at the time of the creation of the mortgage that is actually being foreclosed and is the senior-most mortgage existing at the time of the auction that causes the separation of ownership. There is no reason to refer back to the circumstances at the time of a previously existing but now extinguished senior mortgage.

- Distinguishing the 1990 Precedent: The 1990 Supreme Court case is applicable when multiple mortgages co-exist and are all extinguished by the same foreclosure auction. In that scenario, the SOR is indeed judged based on the circumstances at the time the absolute first-ranking mortgage among those being extinguished was created. However, a mortgage that was extinguished before the auction cannot be treated as equivalent to one being extinguished by the auction.

- Application to the Facts:

- The 1st Mortgage (to B) was created when the Land (owned by Y1) and the Building (then owned by A) were in different ownership.

- However, the 2nd Mortgage (to D, which was the one foreclosed) was created at a time when Y1 owned the Land, and Y1 (along with Y2-Y5) co-owned the Building. As per the 1972 (M90) precedent, this configuration satisfies the "same-owner requirement" for statutory superficies.

- Since the 1st Mortgage was cancelled and its registration erased before the 2nd Mortgage was foreclosed, the relevant point in time for assessing the SOR was the creation of the 2nd Mortgage.

- Therefore, the conditions for a statutory superficies were met, and the Building was entitled to this right. X's claim for building removal and land vacation was consequently dismissed by the Supreme Court, which quashed the lower court judgments and the original District Court decision.

Understanding the "Same-Owner Requirement" (SOR)

The statutory superficies under Civil Code Article 388 is designed to protect existing buildings from demolition when a mortgage foreclosure separates the ownership of the land and the building. A fundamental prerequisite is that "the land and the building existing thereon belong to the same owner" at the time the mortgage is created.

- Purpose: This requirement primarily protects the expectations of the mortgagee. If a mortgagee lends against land that already has a building owned by a different person (and no established land use right for the building), they value the land as potentially being available for unencumbered use if the building owner has no right to keep it there. Allowing a statutory superficies to arise if the landowner later acquires the building (and then defaults on the land mortgage) would unfairly burden the land and reduce its value contrary to the mortgagee's initial assessment.

- Nuance in "Same Owner": As affirmed in this case (citing the 1971 M90 precedent), the SOR can be met even if the land is owned by one individual who is also a co-owner of the building. This reflects a pragmatic approach, recognizing that such a landowner has a vested interest in the building's preservation.

The Significance of a Prior Mortgage Being Extinguished Before Foreclosure

The crucial distinguishing factor in this 2007 judgment was that the senior 1st Mortgage (which was problematic from an SOR perspective at its inception) had been entirely extinguished and its registration cancelled before the foreclosure of the junior 2nd Mortgage.

- Had the 1st Mortgage remained in effect and been the one foreclosed (or foreclosed alongside the 2nd), the 1990 Supreme Court rule would likely have applied, leading to a denial of statutory superficies because, at the creation of that 1st Mortgage, the SOR was not met.

- The elimination of the 1st Mortgage essentially "cleansed the slate" for the purpose of applying the SOR test, allowing the Court to focus on the circumstances prevailing at the creation of the 2nd Mortgage, which was the senior-most effective encumbrance at the time of the auction.

Interaction with Pre-existing Land Use Rights

Legal commentary often notes that statutory superficies issues frequently arise in situations where the parties could have created a conventional land use right (like a lease or a non-statutory superficies) by agreement before the mortgage was established. If a robust, enforceable land use right already exists for the building, a statutory superficies is generally not needed or does not arise.

- In this case, at the time the 1st Mortgage was created (Land owned by Y1, Building by A), Y1 could have granted A a lease.

- Similarly, at the time the 2nd Mortgage was created (Land owned by Y1, Building co-owned by Ys), Y1 (as landowner) could have, in theory, formalized a leasehold right for the benefit of the building co-owners (including herself).

The Supreme Court's willingness to find a statutory superficies in this scenario, despite the theoretical possibility of creating such contractual rights, suggests a judicial inclination to protect existing buildings and prevent their demolition when the foreclosing mortgagee's legitimate expectations (formed at the time their mortgage became the critical encumbrance) are not unfairly undermined. The judgment's reasoning focuses heavily on the expectations and potential prejudice to the junior mortgagee whose mortgage was actually foreclosed, rather than on the theoretical ability of the parties to have structured their land use rights differently at an earlier stage involving a now-defunct mortgage.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of July 6, 2007, provides a very important clarification for a complex scenario involving multiple mortgages and the conditions for statutory superficies. It establishes that if a senior mortgage (which might have been problematic for statutory superficies purposes) is extinguished before a junior mortgage is foreclosed, the "same-owner requirement" is to be assessed at the time the junior mortgage (now the senior-most active mortgage being foreclosed) was created. This pragmatic approach prioritizes the expectations of the currently relevant secured creditors and avoids the need to delve into the historical circumstances of long-extinguished encumbrances, thereby offering a clearer path to determining whether a building is protected by a statutory superficies upon foreclosure. This ruling refines the application of the 1990 Supreme Court precedent and leans towards facilitating the preservation of buildings where it does not cause unforeseen prejudice to the foreclosing mortgagee.