Statutory Limits on Agency Power: Japan's Supreme Court on Registering Deleterious Substance Imports

A First Petty Bench Ruling from February 26, 1981

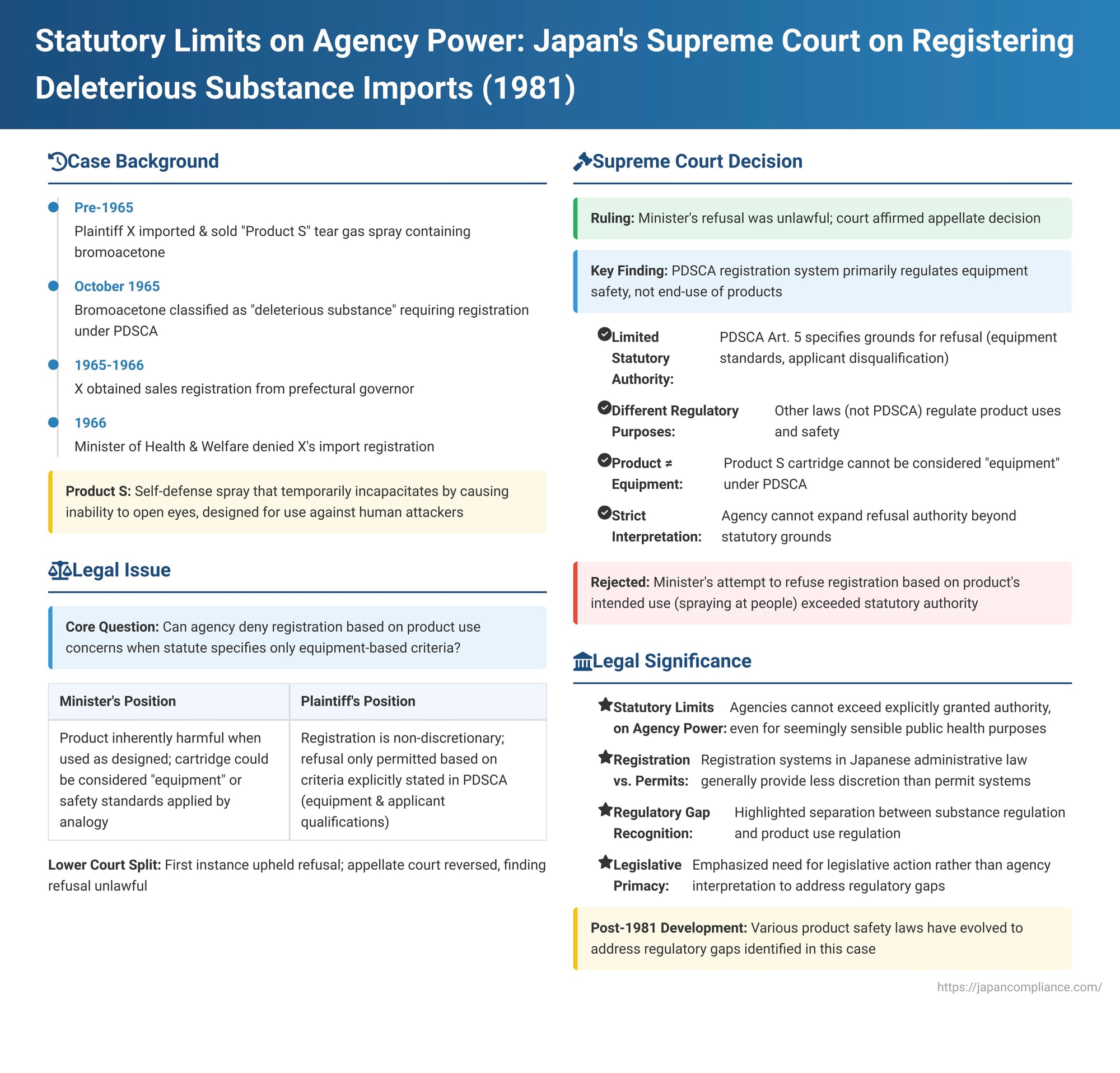

Governments often implement registration or licensing systems to regulate commercial activities involving potentially harmful substances, aiming to balance economic freedom with public health and safety. A crucial legal question arises when an administrative agency denies such registration: on what grounds can it do so? Must the agency strictly adhere to the explicit criteria laid out in the governing statute, or can it invoke broader public interest concerns not specifically mentioned in the registration requirements? The Supreme Court of Japan's First Petty Bench addressed this issue in a significant decision on February 26, 1981 (Showa 52 (Gyo Tsu) No. 137), concerning the refusal to register an importer of a self-defense spray containing a deleterious substance.

The Product and the Problem: "Product S" Self-Defense Spray

The plaintiff, X, was an entrepreneur engaged in the import and sale of a portable self-defense spray device marketed as "Product S" (ストロングライフ - Sutorongu Raifu). This device was designed to spray a diluted solution of bromoacetone (プロムアセトン - puromuaseton), a tear-inducing chemical, to temporarily incapacitate an assailant by causing an inability to keep their eyes open.

The legal landscape for X's business changed in October 1965 when an amendment to the Order Designating Poisonous and Deleterious Substances classified bromoacetone and preparations containing it as "deleterious substances" (劇物 - geki-butsu). Under the Poisonous and Deleterious Substances Control Act (毒物及び劇物取締法 - Dokubutsu oyobi Gekibutsu Torishimari Hō, hereinafter "PDSCA"), this classification meant that specific registrations were now required to legally import or sell products containing bromoacetone. Specifically, Article 3, paragraph 2, and Article 4, paragraph 1 of the PDSCA mandated registration with the Minister of Health and Welfare for an import business and with the relevant prefectural governor for a sales business.

The Registration Refusal

X successfully obtained the necessary registration from the prefectural governor for the sale of Product S. However, when X applied to Y, the Minister of Health and Welfare (at the time), for registration as an importer of the product (referred to as 本件登録 - honken tōroku, "the present registration"), the application was refused.

The Minister's reason for this refusal (本件処分 - honken shobun, "the present disposition") was not based on any alleged deficiency in X's facilities or personal qualifications. Instead, it focused entirely on the nature and intended use of Product S itself: "Product S, containing the deleterious substance bromoacetone, is designed to be sprayed into the eyes of persons or animals, causing functional impairment (though not permanent) by its pharmacological action, leading to an inability to open the eyes, and it has no other use." Essentially, the Minister denied the import registration because the product, when used as intended, was deemed inherently harmful from a public health and safety perspective.

The Legal Battle: Scope of Ministerial Authority

X filed a lawsuit seeking the annulment of the Minister's refusal to register the import business. X argued that the registration process under the PDSCA was a non-discretionary administrative act (羈束行為 - kisoku kōi). According to X, the Minister could only refuse registration based on the specific grounds explicitly listed in the PDSCA, which primarily related to the adequacy of the applicant's equipment and certain disqualifying conditions pertaining to the applicant, not the intended use or inherent danger of the product itself when used as designed.

In defense, the Minister (Y) argued that the bromoacetone-filled cartridges for Product S could be considered "equipment" (設備 - setsubi) under the PDSCA's registration standards, or at least that these standards could be "analogously applied" (類推適用 - ruisui tekiyō). Since this "equipment" was designed to disperse the deleterious substance, it could be seen as failing to meet the safety standards for equipment. Alternatively, the Minister contended that even if X's equipment was technically adequate, registration could still be refused based on the overall purpose of the PDSCA if allowing the import of the specific item would inevitably lead to harm to public health and hygiene, and if this harm significantly outweighed any benefits from importing the item.

The lower courts arrived at conflicting conclusions. The court of first instance upheld the Minister's refusal, reasoning that the PDSCA's equipment standards were not exhaustive and could be interpreted broadly or applied by analogy to refuse registration if public health and safety were clearly endangered. It found that Product S indeed posed a concrete and probable risk. However, the appellate court overturned this decision. It characterized the registration under the PDSCA as akin to a "permit" (許可 - kyoka) in the broad academic sense—an act that lifts a general legal prohibition on an activity. Such restrictions on fundamental freedoms (like the freedom of occupation), the appellate court reasoned, should be kept to the "necessary minimum." It concluded that "registration," by its nature under the PDSCA, imposed a duty on the administrative agency to register an applicant if the statutory requirements (primarily concerning equipment and applicant suitability) were met, leaving no room to refuse based on other considerations like product use. Since X's equipment was not found deficient, the refusal was deemed illegal. The Minister then appealed this ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision of February 26, 1981

The Supreme Court dismissed the Minister's appeal, thereby affirming the appellate court's decision that the refusal to register X's import business was unlawful.

Core Reasoning: PDSCA's Focus on Equipment, Not Product Use:

The Supreme Court's judgment centered on a meticulous interpretation of the PDSCA's regulatory scheme and purpose:

- Statutory Grounds for Refusal: The Court observed that Article 5 of the PDSCA specifies the grounds upon which the Minister can refuse registration for businesses dealing with poisonous or deleterious substances. These grounds primarily include: (a) prior cancellation of the applicant's registration under certain conditions (a disqualification of the person), and (b) a finding that the applicant's equipment does not meet the standards prescribed by the PDSCA Enforcement Regulations (which detail requirements for storage facilities, transportation tools, etc., to prevent accidental spillage, leakage, or dispersion).

- Regulation of Specific Uses: The Court noted that the PDSCA does contain provisions regulating the specific uses of certain highly toxic substances designated as "specified poisonous substances" (特定毒物 - tokutei dokubutsu, as defined in Article 2, paragraph 3 of the Act). For these substances, their use is restricted to specific purposes like academic research or other uses defined by Cabinet Order. However, the Court found that the PDSCA generally "does not provide any particular regulation" concerning the specific uses of other (non-specified) deleterious substances like bromoacetone when used in products.

- Regulation of Harmful Products Under Other Laws: The Court pointed out that numerous other statutes exist in Japan to regulate products containing substances that could be harmful or dangerous to the human body, from the perspective of preventing harm arising from their use. Examples cited included the Food Sanitation Act, the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act, the Act on Control of Household Products Containing Harmful Substances, the Consumer Product Safety Act, and the Act on the Evaluation of Chemical Substances and Regulation of Their Manufacture, etc.

- PDSCA's Legislative Intent: Synthesizing these points, the Supreme Court concluded that the PDSCA itself is designed to regulate businesses dealing with poisonous and deleterious substances "primarily by restricting registration from the aspect of their equipment." The legislative intent, in the Court's view, was that the PDSCA's registration system would ensure safe handling, storage, and transportation of these inherently dangerous raw substances to prevent accidental harm. The question of "for what purpose and in what kind of products" these substances are ultimately used was, with the exception of "specified poisonous substances," generally "not a direct subject of regulation" under the PDSCA itself. Instead, the PDSCA appeared to "entrust to other individual laws the regulation of such matters, with each law addressing them according to its own specific objectives."

- Refusal Based on Product Use Exceeds Statutory Authority: Based on this interpretation, the Supreme Court held that refusing to register X's import business for Product S on the grounds that "harm to the human body may arise from the use of the product according to its intended purpose" was contrary to the PDSCA's legislative scheme. Since the PDSCA conditions the approval or denial of import business registration primarily on whether the applicant's equipment meets the prescribed standards, using the intended application of the end-product as a reason for refusal was impermissible.

- Cartridge Not "Equipment": The Court also summarily affirmed the appellate court's finding that the bromoacetone-containing cartridge of Product S could not be categorized as "equipment" within the meaning of Article 5 of the PDSCA (which pertains to facilities for storing, manufacturing, or transporting bulk substances).

Understanding "Registration" in Administrative Law

This case touches upon the often-debated distinction between different types of administrative regulatory acts, such as "registrations" and "permits."

- Traditionally, a "permit" (許可 - kyoka) is seen as an act that lifts a general legal prohibition on a certain activity, and administrative agencies may sometimes have a degree of discretion in granting permits. "Registration" (登録 - tōroku), on the other hand, has often been viewed as closer to a public notarization or acknowledgment, where if an applicant meets clearly defined statutory requirements, the agency has little or no discretion to refuse.

- However, legal commentary emphasizes that these are academic categorizations, and the actual degree of discretion depends on the specific wording and structure of the particular law in question. The Supreme Court in this case notably refrained from engaging in a broad theoretical discussion of "registration" versus "permit." Instead, it focused on a close reading of the PDSCA itself to determine the legislatively intended grounds for refusing registration.

The PDSCA's Role Among Chemical Regulation Laws

The PDSCA is one of several laws in Japan that regulate chemical substances. Its particular focus, as interpreted by the Supreme Court, is on the inherent hazards (toxicity) of listed substances and ensuring their safe handling through requirements for appropriate equipment and qualified personnel. This distinguishes it from other laws that regulate chemical substances based on their intended use in specific products and the risks associated with those uses (e.g., pharmaceuticals, food additives, household goods). The PDSCA's registration system for importers, manufacturers, and sellers is thus primarily aimed at preventing accidental harm from the substances themselves during their production, storage, transport, and sale, rather than acting as a comprehensive pre-market approval system for all products containing such substances based on their end-use.

Scholarly Debate and Broader Considerations

The Supreme Court's decision, while lauded by some for its adherence to strict statutory interpretation and protection of economic liberty, has also been subject to debate among legal scholars.

- Arguments Supporting the Decision: Many view the judgment as correctly upholding the principle that administrative agencies cannot expand their regulatory powers beyond what is granted by statute. If the PDSCA ties registration refusal to equipment standards, then refusing based on product use, however well-intentioned, is an overreach.

- Arguments Critical of the Decision: Others have expressed concern, arguing from a public safety perspective. They suggest that a broader, purposive interpretation of the PDSCA might have allowed the Minister to refuse registration for a product designed to be sprayed at people, especially if other laws at the time did not adequately address the specific risks posed by such a product. This view often emphasizes a "three-party" model of regulation (regulator, regulated business, and the public/third parties protected by the regulation), arguing for greater weight to be given to the protection of public health.

The case also implicitly raises broader policy questions about how novel products, such as chemical self-defense sprays, should be regulated—whether through existing laws governing deleterious substances based on handling risks, or through product-specific safety legislation focusing on intended use and potential misuse.

Conclusion

The 1981 Supreme Court decision concerning the import registration for "Product S" is a significant judgment that underscores the importance of administrative agencies acting strictly within the confines of their statutory authority. By finding that the PDSCA's registration scheme for importers of deleterious substances primarily focused on equipment safety rather than the intended end-use of products containing such substances, the Court ruled that the Minister of Health and Welfare could not refuse registration based on concerns about the product's application. This case serves as a strong reminder that if an agency believes a particular product or activity poses a public health risk not adequately covered by its existing regulatory tools, the appropriate course is generally to seek specific legislative authorization to address that risk, rather than stretching the interpretation of existing laws beyond their intended scope. It emphasizes the legislature's primary role in defining the grounds for restricting commercial activities, particularly when fundamental economic freedoms are involved.