Statutory Land Rights in Japan: Co-ownership Complicates Mortgage Foreclosures

Date of Judgment: December 20, 1994

Case Name: Action for Removal of Building and Vacant Possession of Land, etc.

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

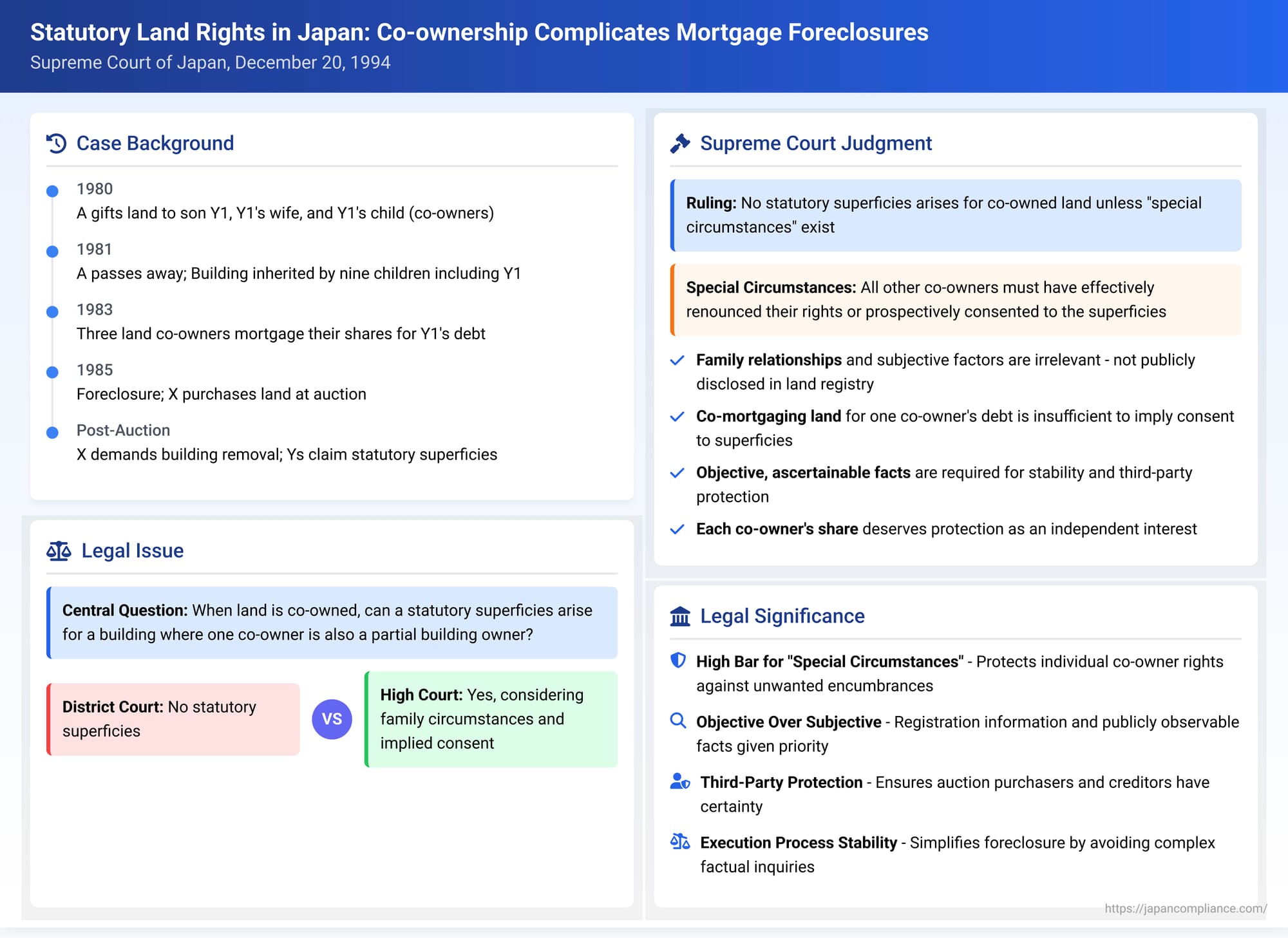

The Japanese legal doctrine of "statutory superficies" (hōtei chijōken), established by Article 388 of the Civil Code, is a vital mechanism aimed at preventing the economic waste that would result from demolishing a perfectly usable building. It arises when land and a building on it, initially under common ownership, come to have different owners due to the foreclosure of a mortgage placed on either the land or the building (or both). The building owner is then deemed to have a statutory right to use the land. A cornerstone for this right is the "same-owner requirement" (SOR): the land and building must have belonged to the same owner when the mortgage was created. However, real-world property ownership is often complex, involving co-ownership of either the land or the building, or both. The Supreme Court of Japan addressed such a complex co-ownership scenario in a key judgment on December 20, 1994, clarifying the strict conditions under which a statutory superficies can arise when co-owned land is mortgaged.

The Factual Background: A Web of Co-ownership and a Land Mortgage

The case involved a family, their property, and a subsequent mortgage foreclosure:

- Land Ownership: In February 1980, A gifted a piece of land ("the Land") to his son Y1, Y1's wife, and Y1's child, making them co-owners of the Land. The background to this was A's intention to provide for Y1's future livelihood by eventually giving him both the Land and an existing building on it ("the Building"). However, due to concerns about Y1's sole ability to pay the gift tax, the Land was gifted to the three of them jointly.

- Building Ownership: At the time the Land was gifted, the Building on it remained in A's ownership. This was because Y1 had experienced business difficulties, and there was a fear that if the Building were transferred to Y1's name, his creditors might seize it.

- Inheritance of Building: In January 1981, A passed away. The Building was then inherited by A's nine children, including Y1 and Y2. Thus, the Building became co-owned by these nine heirs.

- Mortgage on the Land: In December 1983, the three co-owners of the Land (Y1, his wife, and his child) jointly created a mortgage over their respective shares in the Land. This mortgage was granted to B Finance Corp. and was established to secure a personal debt owed solely by Y1. The mortgage was duly registered.

- Foreclosure and Sale to X: In December 1985, B Finance Corp. initiated foreclosure proceedings based on this mortgage on the Land. X purchased the Land at the ensuing auction and acquired ownership. Notably, the execution court's official property details report prepared for the auction stated "None" in the section describing any "superficies deemed to have been created by sale."

- X's Lawsuit: X, as the new owner of the Land, sued the Ys (all nine co-owners of the Building, including Y1 and Y2), demanding that they remove the Building and return vacant possession of the Land. The Ys defended this claim by asserting that a statutory superficies had arisen for the Building.

The Legal Puzzle: Statutory Superficies on Co-owned Land?

The path of the case through the lower courts highlighted the complexity of the issue:

- The District Court (Sapporo District Court): Denied the existence of a statutory superficies and ruled in favor of X, ordering the building's removal.

- The High Court (Sapporo High Court): Reversed the District Court's decision. It found that a statutory superficies had arisen. The High Court reasoned that where all co-owners of land jointly mortgage their entire collective interest, and considering the specific family circumstances and the original owner A's intent, it could be deemed that all land co-owners had effectively consented to a statutory superficies arising for the benefit of the building co-owners (among whom Y1 was a key figure).

X appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling (December 20, 1994): Strict Conditions for Co-owned Land

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision and reinstated the District Court's ruling, meaning no statutory superficies was recognized. The Supreme Court laid down a strict framework for assessing statutory superficies when co-owned land is involved.

1. General Principle for Co-owned Land:

The Court began by affirming a general principle: "Each co-owner possesses an independent share in the co-owned property, which is of the same nature as ownership. Moreover, a superficies over the entire co-owned land becomes a burden on all co-owners. Therefore, even if circumstances that would cause a statutory superficies to be deemed created for one land co-owner under Article 388 of the Civil Code have arisen only with respect to that one co-owner, a statutory superficies does not arise for the co-owned land unless there are special circumstances under which it can be found that the other co-owners had, for example, effectively renounced their right to use and profit from the land based on their shares and entrusted its disposition to that one co-owner, thereby being deemed to have prospectively consented to the creation of a statutory superficies." The Court cited its prior rulings (Supreme Court, December 23, 1954, Minshū Vol. 8, No. 12, p. 2235; Supreme Court, November 4, 1969, Minshū Vol. 23, No. 11, p. 1968) in support of this framework.

2. Application to This Case – No "Special Circumstances" Found:

The Supreme Court then applied this framework to the specific facts, finding that the requisite "special circumstances" did not exist:

- Rejection of Subjective Factors (Family Ties): The Court acknowledged that Y1's wife and child (the other land co-owners) were family members who had jointly mortgaged their land shares to secure Y1's debt, which might suggest a degree of implicit consent to Y1's land use for the building. However, it firmly stated: "Circumstances such as the personal relationships between land co-owners are not objectively and clearly publicized by means such as entries in the land register and are unknowable to third parties. Considering that the existence or non-existence of a statutory superficies greatly affects the interests not only of the other land co-owners but also of third parties such as auction purchasers of the said land, it is not appropriate to determine the establishment of a statutory superficies based on the presence or absence of such circumstances."

- Insufficiency of Objective Co-mortgaging Facts: The Court found that the only truly objective circumstance was that all land co-owners had jointly mortgaged their respective shares in the Land to secure a debt owed by Y1, who was merely one of the nine co-owners of the Building. This fact alone was deemed insufficient to infer that the other land co-owners (Y1's wife and child) had prospectively consented to the creation of a statutory superficies that would burden their shares in the Land.

- Rationale for Denying Implied Consent:

- Land Co-owners' Normal Intentions: The Court reasoned that if merely co-mortgaging land shares for the debt of one land co-owner (who is also a minority building co-owner) were enough to establish a statutory superficies, it would transform any informal permission the other land co-owners might have given for the building's existence into a powerful real right (a superficies). This would significantly devalue the land, an outcome contrary to the usual intention of land co-owners to maintain and fully utilize the value of their individual shares.

- Protection of Third-Party Expectations and Execution Stability: Such a result would also harm the legitimate expectations of third parties, such as general creditors of the other land co-owners, any junior mortgagees of their land shares, or subsequent auction purchasers of the land. It would, the Court stated, undermine the legal stability of compulsory execution proceedings and was therefore impermissible.

The Principle of Protecting Co-owners' Independent Shares

This judgment underscores the importance of each co-owner's independent share rights in Japanese law. The Supreme Court's reasoning consistently emphasizes that burdening the entire co-owned land with a statutory superficies—a significant encumbrance—requires something more than the conditions for statutory superficies being met for just one co-owner, especially when that co-owner does not even solely own the building. The consent of the other co-owners (either actual or deemed under very strict, objectively ascertainable "special circumstances") is paramount.

Justice Chikusa Hideo's Supplementary Opinion:

The Presiding Justice, Chikusa Hideo, provided a supplementary opinion that further illuminated the Court's reasoning. He stressed that statutory superficies arises from a foreclosure auction, and therefore, interpreting its conditions must consider the need for proper and swift conduct of auction proceedings and the certainty of legal relationships formed as a result. To ensure this, the determination of whether a statutory superficies exists should be based only on objective information readily available to anyone, primarily from the land register. Complex factual inquiries into unpublicized internal family dynamics or subjective intentions are unsuitable for the auction process. Justice Chikusa pointed out that while one might sympathize with the building owners, the existing legal framework for statutory superficies is becoming outdated and ill-suited to modern complex property co-ownership and land use patterns. He suggested that legislative reform might be desirable to create a system (perhaps a "statutory leasehold") that better reflects current socio-economic realities and can be determined more clearly within the auction process.

Implications for Statutory Superficies in Co-ownership Scenarios

The 1994 Supreme Court judgment significantly clarifies and arguably narrows the conditions under which a statutory superficies can arise when the land is co-owned:

- High Bar for "Special Circumstances": It establishes a high threshold for finding the "special circumstances" that would imply consent from all land co-owners. Mere family relationships or even the act of all land co-owners jointly mortgaging their shares to secure the debt of one co-owner (who is also a building co-owner) are generally insufficient.

- Emphasis on Objective Factors and Third-Party Protection: The decision prioritizes objective, publicly ascertainable facts and the protection of the expectations of third parties (like auction purchasers and other creditors) who rely on the stability and predictability of the execution process.

- Continued Relevance of Prior Precedents for Specific "Special Circumstances": The judgment acknowledges its prior ruling from 1969 (the "factual division" of land case), where "special circumstances" were found based on objectively discernible agreements and actions that implied a renunciation of rights and consent to disposition by the other co-owners. This suggests that while subjective factors are out, concrete, objectively verifiable actions or agreements that demonstrate consent remain relevant.

Remaining Complexities and Unresolved Issues

Despite this clarification, the application of statutory superficies in co-ownership situations remains intricate:

- Interaction with Sole Landowner / Co-owned Building Scenario: How does this judgment precisely interact with the well-established rule (from the 1971 "M90" Supreme Court case, also cited in M88) that if land is solely owned by individual A, and the building on it is co-owned by A and B, a statutory superficies does arise if A mortgages the land? This 1994 case dealt with co-owned land. The interplay between these different co-ownership configurations continues to be analyzed.

- Degree of Building Co-ownership: This judgment noted that Y1 was only one of nine co-owners of the building. Would the outcome change if the land co-owner whose debt was secured also held a dominant share in the building, or if all land co-owners were also all the building co-owners? These questions remain open for further judicial clarification or academic debate.

- Self-Leasehold Possibilities: The rationale for statutory superficies (Civil Code Art. 388) partly stems from the fact that if land and building are owned by the exact same person, that person cannot create a conventional lease for themselves to protect the building. However, the Land and Building Lease Act (Article 15) now allows for the creation of a "self-leasehold" (jiko shakuchi-ken) in certain situations, particularly if the leasehold right is to be co-owned. This raises the question: if building co-owners could have created a self-leasehold to protect their building's use of the land, should this affect the availability of a statutory superficies? Some scholars argue against a sweeping denial of statutory superficies merely because a self-leasehold might have been theoretically possible.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of December 20, 1994, significantly refines the doctrine of statutory superficies in Japan, particularly in the challenging context of co-owned land. By setting a high bar and emphasizing objective, publicly ascertainable evidence of "special circumstances" demonstrating consent from all land co-owners, the Court prioritized the protection of individual co-owners' share rights and the stability and predictability of mortgage foreclosure proceedings. While generally making it more difficult for a statutory superficies to arise when land is co-owned and mortgaged for the debt of only one co-owner (even if others join in the mortgage), the decision underscores the judiciary's careful balancing of historical doctrines with the practical realities of modern property transactions and the rights of all involved parties.