State vs. Employer Liability: Japan Supreme Court Clarifies Delegated Child Welfare Duties (2007)

Japan Supreme Court 2007: negligence at a private child welfare home performing public duties makes the prefecture liable, not the employer.

TL;DR

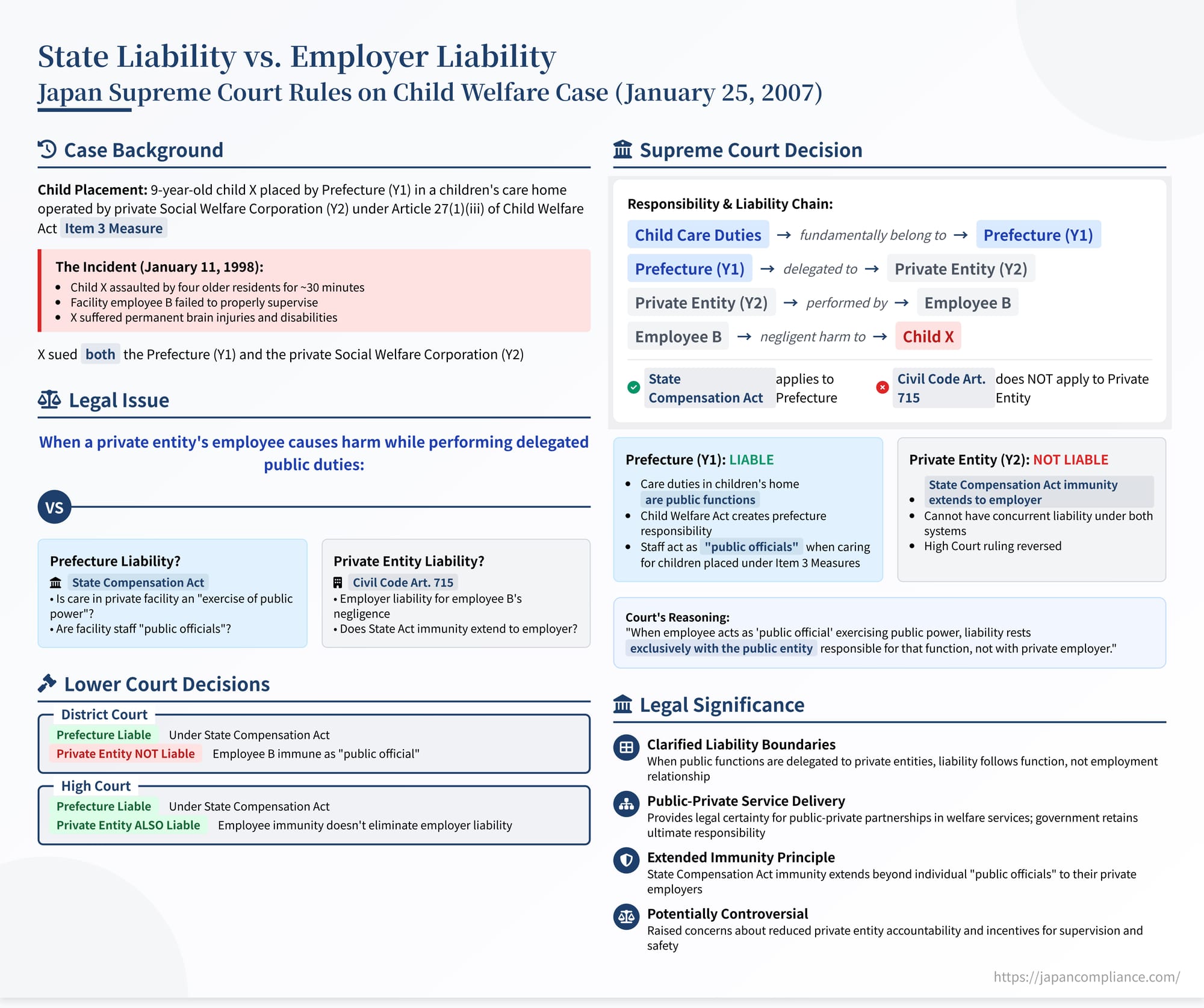

Japan’s Supreme Court (Jan 25 2007) held that when a private child‑welfare home cares for a child under a prefectural placement order, its staff act as public officials. Negligent harm therefore triggers prefectural liability under the State Compensation Act, while the private employer is immune from vicarious liability.

Table of Contents

- The Incident: Tragedy in a Children's Care Home

- The Legal Claims and Conflicting Lower Court Views

- The Supreme Court's Decision – Part 1: Prefecture's Liability Confirmed

- The Supreme Court's Decision – Part 2: Private Employer's Liability Denied

- Final Outcome and Significance

In Japan, as in many countries, the delivery of public services is increasingly entrusted to private entities. This delegation raises complex legal questions about liability when things go wrong. If an employee of a private organization, acting under the authority delegated by the state – for instance, providing child welfare services – negligently causes harm, who bears the legal responsibility? Is it the state, under the State Compensation Act (Kokka Baishō Hō) which governs liability for wrongful acts committed in the exercise of public power? Is it the private organization, as the employer, under the general principles of vicarious liability found in the Civil Code? Or could both be held liable? A key decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on January 25, 2007, addressed this intersection of public and private liability in the sensitive context of child protective services.

The Incident: Tragedy in a Children's Care Home

The case stemmed from a tragic incident involving X, a child born in November 1988. Due to X's mother's illness, which made adequate care at home impossible, the prefectural government (defendant Y1, representing Aichi Prefecture) placed X in A Gakuen, a children's care home (jidō yōgo shisetsu), in January 1992. A Gakuen was operated by Y2, a private social welfare corporation. This placement was made under the authority of Article 27, Paragraph 1, Item 3 of the Child Welfare Act – an administrative measure known as an "Item 3 Measure" (san-gō sochi) used for children needing protective care.

On January 11, 1998, when X was nine years old, X was assaulted over approximately 30 minutes by four older children (aged 12-15) who were also residents of A Gakuen under Item 3 Measures. The assault occurred within the facility premises. It happened shortly after an employee of A Gakuen, referred to as B, had reprimanded one of the assailants for kicking X. The assault took place in apparent retaliation while employee B had briefly returned to the facility's office.

X suffered extremely severe injuries, including right-sided hemiparesis (partial paralysis) and traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage. Despite hospitalization and treatment, X was left with permanent disabilities, including higher brain dysfunction. It was established in the lower courts, and not contested at the Supreme Court level, that employee B had been negligent in fulfilling the duty to properly supervise and protect the children residing in the facility.

The Legal Claims and Conflicting Lower Court Views

X sued both the prefecture (Y1) and the social welfare corporation operating the home (Y2) for damages resulting from employee B's negligence.

- Claim against the Prefecture (Y1): X argued that the day-to-day care and supervision (yōiku kango) provided by the staff of A Gakuen, although a private facility, was conducted pursuant to the prefecture's statutory placement decision (the Item 3 Measure). This care, X contended, constituted an "exercise of public power" (kōkenryoku no kōshi) by individuals acting effectively as "public officials" (kōmuin) on behalf of the prefecture. Therefore, Y1 (the Prefecture) should be liable for the damages caused by B's negligence under Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act.

- Claim against the Social Welfare Corporation (Y2): X argued that, regardless of the prefecture's potential liability under state compensation law, Y2 was the direct employer of the negligent employee, B. Therefore, Y2 should be held liable under Article 715 of the Civil Code, which establishes employer liability (respondeat superior) for torts committed by employees in the course of their employment.

The lower courts agreed on the prefecture's liability but diverged sharply on the liability of the private employer:

- District Court (Nagoya): Found the Prefecture (Y1) liable under the State Compensation Act. It agreed that the care provided by Y2 under the Item 3 Measure was a function with a high degree of public character, qualifying as an "exercise of public power." Employee B was thus deemed a "public official" for the purposes of the State Compensation Act. However, the District Court dismissed the claim against Y2 (the Social Welfare Corporation). It reasoned that because B's actions fell under the State Compensation Act (making B a "public official" in that context), B enjoyed personal immunity from civil tort liability. Since the employee was not personally liable, the court concluded, the employer (Y2) could not be held vicariously liable under Civil Code Article 715.

- High Court (Nagoya): Upheld the finding of liability against the Prefecture (Y1) under the State Compensation Act, using similar reasoning. However, the High Court reversed the dismissal of the claim against Y2. It held that Article 1(1) of the State Compensation Act only eliminates the personal liability of the individual official; it does not negate the inherent wrongfulness of the negligent act. Therefore, the High Court reasoned, the Act does not preclude holding the employer (Y2) liable under Civil Code Article 715, even if the employee (B) is considered a "public official" for state compensation purposes. The High Court found Y2 liable alongside Y1.

Both Y1 (Prefecture) and Y2 (Social Welfare Corporation) sought review by the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision – Part 1: Prefecture's Liability Confirmed

The Supreme Court first addressed the liability of the prefecture (Y1). It undertook a detailed analysis of the Child Welfare Act's framework:

- The Act establishes a shared responsibility between the state/local government and parents for the healthy upbringing of children (Article 2).

- Prefectures are mandated to establish child guidance centers to fulfill this responsibility (Article 15).

- Prefectures have the power and duty to take protective measures for children who lack adequate parental care, including placing them in children's care homes like A Gakuen (Article 27(1)(iii)).

- These placements can even be made against parental wishes in cases of abuse, with family court approval (Article 28).

- When a prefecture places a child in a non-national care home under an Item 3 Measure, the prefecture is responsible for bearing the costs necessary to maintain the minimum standards of care set by the national government (Article 50(vii)).

- Directors of children's care homes are granted significant authority, including the power to exercise parental rights over children without parents/guardians and the power to take necessary measures for the welfare (including care, education, and discipline) of all resident children (Article 47).

Based on this statutory structure and the underlying purpose of the Act, the Supreme Court concluded that the care and supervision provided within a children's care home to children placed there under an Item 3 Measure is, in essence, a duty (jimu) that fundamentally belongs to the prefecture. The Act presupposes a guardianship-like (kōkenteki) responsibility of the state in these situations.

Consequently, the Court reasoned, the director and staff of a private children's care home, when providing daily care and supervision to these children, are acting pursuant to delegated public authority derived from the prefecture's placement decision. They are exercising these powers on behalf of the prefecture.

Therefore, the Supreme Court affirmed the lower courts' finding: the care and supervision provided by the staff of A Gakuen (operated by Y2) to X, who was placed there by Y1 under an Item 3 Measure, constitutes the performance of official duties by public officials acting in the exercise of the prefecture's public power. The High Court's conclusion that the Prefecture (Y1) was liable under Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act for the damages caused by employee B's negligence was correct. Y1's appeal on this point was dismissed.

The Supreme Court's Decision – Part 2: Private Employer's Liability Denied

The second, and more novel, issue was the liability of the private employer, Y2 (the Social Welfare Corporation). The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision on this point.

The Court started by reaffirming a long-standing interpretation of the State Compensation Act: Article 1, Paragraph 1, while imposing liability on the state or public entity, simultaneously shields the individual public official from personal liability under the Civil Code's general tort provision (Article 709). This immunity applies even if the official acted negligently or intentionally (though internal disciplinary action or state claims for indemnity against the official in cases of gross negligence or intent are separate matters).

The Supreme Court then extended this principle to the employer of an individual deemed to be acting as a "public official." It reasoned:

- The purpose of the immunity granted by the State Compensation Act framework is to ensure that liability for harm caused during the exercise of public functions rests with the public entity responsible for those functions.

- If an employee of a private entity causes harm while exercising delegated public power, triggering the state's liability under State Compensation Act Art. 1(1), the logic of channeling liability requires consistency.

- Allowing a concurrent claim against the private employer under Civil Code Article 715 (employer liability) would undermine this channeling function. It would create a situation where liability for the same act rests simultaneously with the state (under public law principles) and the private employer (under general private law principles).

- This concurrent liability could lead to complex and potentially inconsistent outcomes, particularly concerning rights of recourse or indemnity between the state, the private employer, and the employee.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the principle embedded in State Compensation Act Article 1(1) dictates that when the state or public entity is liable under that Act for the actions of a private entity's employee (because those actions constituted an exercise of public power), not only is the employee personally immune from tort claims (Civil Code Art. 709), but the private employer is also immune from vicarious liability claims (Civil Code Art. 715).

Applying this to the case facts:

- The care provided by employee B was an exercise of Y1's public power.

- Y1 (Prefecture) was liable under State Compensation Act Art. 1(1).

- Therefore, B's employer, Y2 (Social Welfare Corporation), could not be held liable under Civil Code Art. 715.

The High Court had erred in finding Y2 liable.

Final Outcome and Significance

The Supreme Court's final judgment:

- Dismissed the appeal of the Prefecture (Y1), confirming its liability under the State Compensation Act.

- Granted the appeal of the Social Welfare Corporation (Y2), reversing the High Court's finding of liability against it and dismissing X's claim against Y2.

This decision significantly clarified the interplay between state compensation law and private tort law when public functions are delegated to private entities. It established a clear rule: liability follows the nature of the function. If the harmful act occurs during the exercise of delegated public power, liability rests solely with the state/public entity under the State Compensation Act, displacing potential liability of the private employer under the Civil Code's employer liability rules.

This ruling has major implications for the allocation of risk and responsibility in public-private partnerships and delegated service provision in Japan. While providing legal certainty, it also sparked debate. Critics argued that absolving the private employer might reduce incentives for that entity to ensure safety and proper supervision within its own operations. Alternative legal theories, such as holding the private entity directly liable for its own organizational negligence (rather than vicariously for the employee's act) or for breach of a direct safety duty owed to service users, were noted in academic commentary as potential avenues not explored in this specific case, but relevant for future considerations. The ruling's scope might also be limited primarily to situations involving significant delegation of state authority, like the child protection measures under the Child Welfare Act, and may not automatically apply to all publicly funded but less authoritatively delegated services.

Nonetheless, the core message of the 2007 judgment stands: in the context of delegated public functions like statutory child placement and care, negligent harm caused by the private provider's employee results in liability for the state under the State Compensation Act, while precluding liability for the private employer under general tort principles.

- Workers’ Comp vs. Consolation Money: Japan’s Supreme Court Separates Financial and Non‑Financial Damages

- Child Abuse in Japan: Reporting Obligations and Workplace Considerations for Companies

- Challenging a Father’s Name After Death: Japan’s Supreme Court on Belated Paternity Invalidation Claims

- Overview of Act on Partial Amendment of the Child Welfare Act (MHLW)