Standing Up for Samurai Bondholders: How Japan's Supreme Court Empowered Bond Administrators

Date of Judgment: June 2, 2016

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Introduction

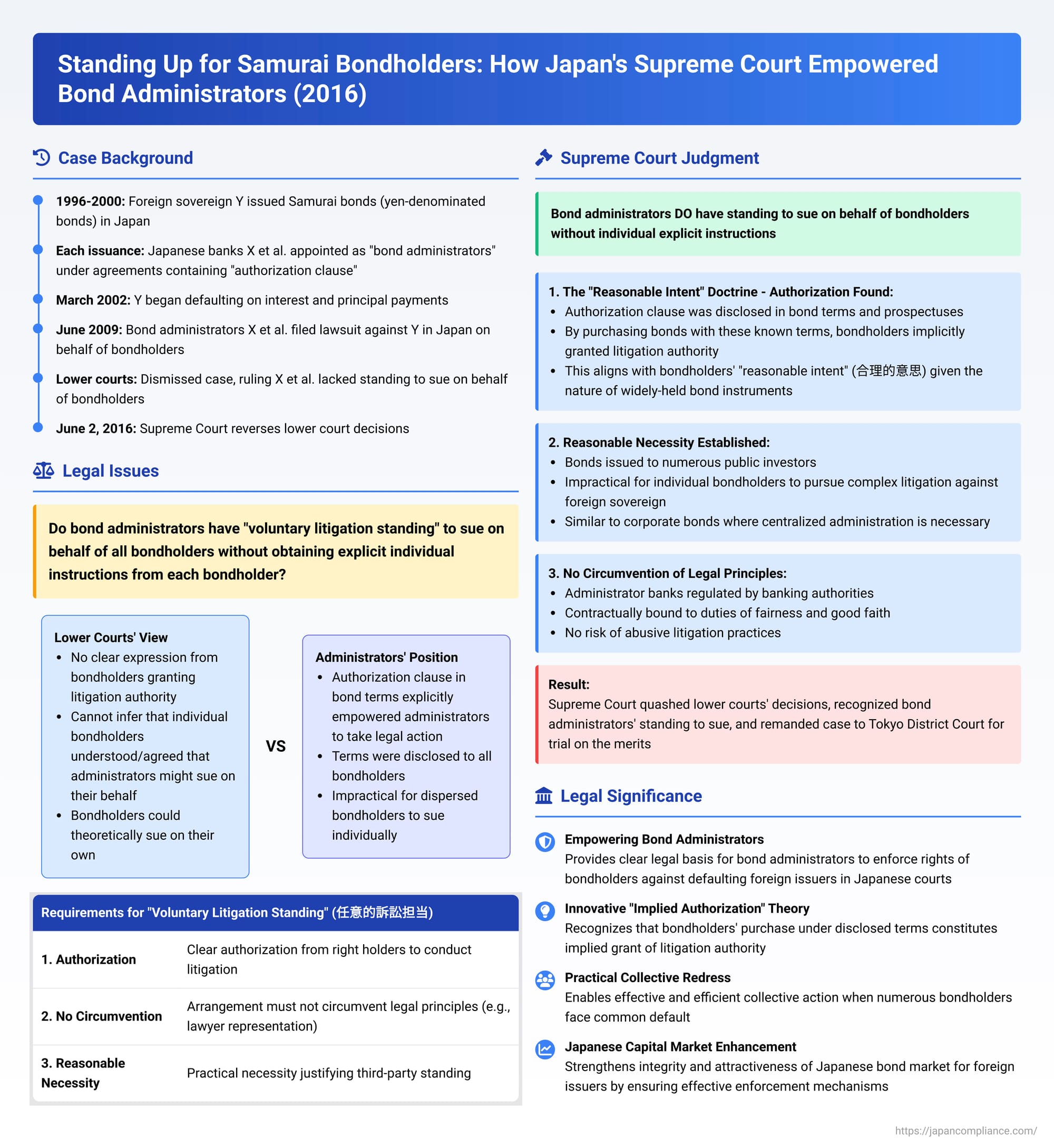

"Samurai bonds"—yen-denominated bonds issued in Japan by foreign governments or corporations—are a significant feature of the Japanese financial market. When these bonds are issued, a financial institution, typically a bank, is often appointed as a "bond administrator" to manage various aspects of the bond on behalf of the numerous, often widely dispersed, bondholders. A critical question arises if the foreign issuer defaults on its payment obligations: Does the bond administrator have the legal right—the "standing to sue"—to take the issuer to court in Japan on behalf of all the bondholders, even without obtaining explicit individual instructions from each and every one of them?

This complex issue of standing, particularly the concept of "voluntary litigation standing," was at the heart of a landmark decision by the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on June 2, 2016.

The Concept of "Voluntary Litigation Standing" (Nin'iteki Soshō Tantō)

Under Japanese law, the general principle is that only the person who directly holds a legal right can file a lawsuit to enforce that right. However, there are exceptions. "Voluntary litigation standing" (任意的訴訟担当 - nin'iteki soshō tantō) is one such exception, where a third party, who is not the original holder of the right, is permitted to conduct litigation on behalf of the actual right holder(s), provided certain conditions are met.

Based on a 1970 Supreme Court (Grand Bench) precedent, the key requirements for recognizing such voluntary litigation standing typically include:

- Clear authorization to conduct the litigation, granted by the original holder(s) of the right.

- The arrangement must not pose a risk of circumventing fundamental legal principles, such as the general requirement for parties to be represented by a lawyer (the principle of lawyer representation) or the prohibition against "litigation trusts" (where a claim might be transferred to someone merely for the purpose of suing on it).

- There must be a "reasonable necessity" to allow such third-party standing, often because it is impractical or unduly burdensome for the original right holders to pursue the claim themselves.

The Case of Foreign Sovereign Y's Samurai Bonds

The case before the Supreme Court involved the following:

- A foreign sovereign state, Y (the appellee), had issued several series of yen-denominated "Samurai bonds" in Japan between 1996 and 2000.

- For each bond issuance, Y entered into "bond administration agreements" with Japanese banks, X et al. (the appellants), appointing them as bond administration companies.

- These administration agreements were governed by Japanese law and crucially included an "authorization clause" (本件授権条項 - honken jugen jōkō). This clause explicitly granted the bond administrators (X et al.) the authority and the duty to undertake all necessary judicial (court-based) or extra-judicial (out-of-court) actions to receive payments due on the bonds or to otherwise secure the realization of claims for the benefit of the bondholders. This clause was modeled on similar powers granted to statutory administrators of corporate bonds under Japan's (then) Commercial Code.

- The terms of this authorization clause were also incorporated into the official "terms of bonds" (債券の要項 - saiken no yōkō) for each bond series. These terms were printed on the reverse side of the physical bond certificates and their substantive content, including the authorization clause, was disclosed to investors in the bond prospectuses.

- Y, the foreign sovereign issuer, subsequently defaulted on its interest and principal payment obligations for these Samurai bonds starting around March 2002.

- In June 2009, the bond administrators, X et al., filed a lawsuit in Japan against Y, seeking recovery of the outstanding redemption amounts and interest on behalf of the specified bondholders.

- Lower Court Rulings: Both the District Court and the High Court dismissed the lawsuit. They found that X et al., the bond administrators, lacked the necessary standing to sue. The High Court reasoned that it was difficult to infer that individual bondholders, when purchasing the bonds, had specifically understood and agreed that the administrators might initiate litigation on their behalf. Thus, the courts found no clear expression of intent from the bondholders to grant litigation authority, and also questioned the "reasonable necessity" for such standing, given that individual bondholders could theoretically sue on their own.

The bond administrators (X et al.) appealed this dismissal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (June 2, 2016)

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, reversed the lower courts' rulings and recognized the standing of the bond administrators (X et al.) to sue on behalf of the bondholders. The Court meticulously applied the three-pronged test for voluntary litigation standing.

1. Authorization from Bondholders – The "Reasonable Intent" Doctrine

This was the most innovative and crucial part of the Supreme Court's reasoning.

- The Court acknowledged that the administration agreements, which included the explicit authorization clause empowering X et al. to take legal action, were essentially "contracts for the benefit of third parties"—those third parties being the bondholders.

- The terms of this authorization clause were not hidden; they were an integral part of the bond terms and were clearly disclosed to investors through prospectuses and on the bond certificates themselves.

- The "Reasonable Intent" of Bondholders: The Supreme Court then considered the nature of these Samurai bonds. It noted their similarity to corporate bonds, which are typically issued to a large number of public investors. For such widely-held instruments, it is common and generally understood that an administrator or trustee acts to protect the collective interests of dispersed bondholders, including taking enforcement action. The Court reasoned that the explicit authorization clause, mirroring the powers of statutory corporate bond administrators, aligned with the "reasonable intent" (合理的意思 - gōriteki ishi) of the individuals purchasing these Samurai bonds.

- Implied Grant of Authority: Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that by purchasing these bonds with these clearly disclosed terms (which included the administrators' authority to litigate), the bondholders were deemed to have implicitly expressed their intention to benefit from the comprehensive bond administration services offered by X et al., including the pursuit of legal claims if necessary. This act of purchase, under these known terms, constituted a sufficient grant of litigation authority from the bondholders to the administrators. Academic commentary aptly describes this as a "constructive recognition" of implied authorization based on the bondholders' reasonable intentions and the context of the investment.

2. No Circumvention of Legal Principles and Demonstration of Reasonable Necessity

The Supreme Court then found that allowing the bond administrators to sue satisfied the other prongs of the test for voluntary litigation standing:

- Reasonable Necessity: The Samurai bonds in question were issued to numerous members of the general public. The Court recognized that it would be highly impractical and unreasonable to expect each individual bondholder, many of whom might hold relatively small amounts, to independently pursue complex and potentially costly legal action against a foreign sovereign issuer in the event of a default. This situation is analogous to that of corporate bonds, where statutory bond administration systems were established precisely to protect numerous and dispersed public bondholders by providing a centralized entity to enforce their rights.

- Systemic Design and Intent: The parties involved in the bond issuance (the sovereign issuer Y and the administrator banks X et al.) had deliberately structured the bond administration mechanism, including the explicit authorization clause, to emulate the well-understood and established system for corporate bond administrators in Japan. This was a common practice for Samurai bonds and aimed to create a workable framework for managing such securities and protecting investor interests.

- No Circumvention of Legal Principles: The bond administrators, X et al., were all regulated banks in Japan, subject to the oversight of banking authorities. Furthermore, their administration agreements explicitly bound them to duties of fairness, good faith, and the care of a good manager towards the bondholders. Given these regulatory and contractual obligations, the Supreme Court found that X et al. could be expected to exercise any litigation rights appropriately and diligently on behalf of the bondholders. Therefore, recognizing their standing to sue did not pose a risk of circumventing the principle of lawyer representation or the prohibitions on abusive litigation trusts.

Conclusion on Standing: Based on this comprehensive analysis, the Supreme Court determined that the bond administrators, X et al., fulfilled all the necessary requirements for voluntary litigation standing and were therefore proper plaintiffs to bring the lawsuit against the defaulting foreign sovereign issuer, Y.

Outcome: The Supreme Court quashed the decisions of the High Court and the District Court (which had also presumably dismissed the case for lack of standing). The case was remanded to the Tokyo District Court for a trial on the merits of the bond default claims.

Significance of the Ruling

This 2016 Supreme Court decision is of major importance, particularly for the Samurai bond market and the broader understanding of litigation standing in Japan:

- Empowering Bond Administrators for Foreign Sovereign Debt: It provides a clear legal basis and a vital mechanism for bond administrators of Samurai bonds (and potentially other similarly structured foreign-issued bonds in Japan) to effectively enforce the rights of bondholders against defaulting foreign issuers within the Japanese legal system. This is crucial for investor confidence.

- Landmark Recognition of "Implied Authorization" Based on Reasonable Intent: The most legally significant aspect of the ruling is the Court's innovative approach to finding the necessary "authorization" from bondholders. By inferring a grant of litigation authority from the bondholders' "reasonable intent" based on their purchase of bonds with clearly disclosed terms that included administrator litigation powers, the Court adopted a pragmatic and purposive interpretation. This was particularly important given the impracticality of obtaining explicit, individual mandates from potentially thousands of dispersed international bondholders.

- Facilitating Practical Collective Redress: The decision offers a practical and efficient solution for achieving collective redress when numerous bondholders are faced with a common default by an issuer. It avoids the scenario of potentially hundreds or thousands of small, uncoordinated, and likely uneconomical individual lawsuits.

- Considerations for Future Application: While widely seen as a positive development, academic commentary (as noted in the PDF source ) suggests that the precise scope and limits of this "reasonable intent" and "implied authorization" doctrine might be subject to further debate and refinement in future cases presenting different factual scenarios.

Conclusion

The 2016 Supreme Court decision regarding the standing of Samurai bond administrators is a landmark judgment in Japanese financial and procedural law. By recognizing the implied authorization of these administrators to sue on behalf of all bondholders – based on the bondholders' reasonable intent inferred from disclosed terms and the practical necessities of representing numerous investors – the Court has provided a robust and effective means to protect investors in foreign sovereign debt issued in Japan. This ruling demonstrates a flexible and purposive approach to legal interpretation, ensuring that appropriate mechanisms exist for the enforcement of rights in the context of complex, widely-held financial instruments, thereby bolstering the integrity and attractiveness of the Japanese capital market for foreign issuers.