Standing to Sue in Distribution Objection Lawsuits: A 1994 Japanese Supreme Court Ruling

Case Name: Principal Action for Objection to Distribution; Counterclaim for Damages

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 2 (O) No. 1128

Date of Judgment: July 14, 1994

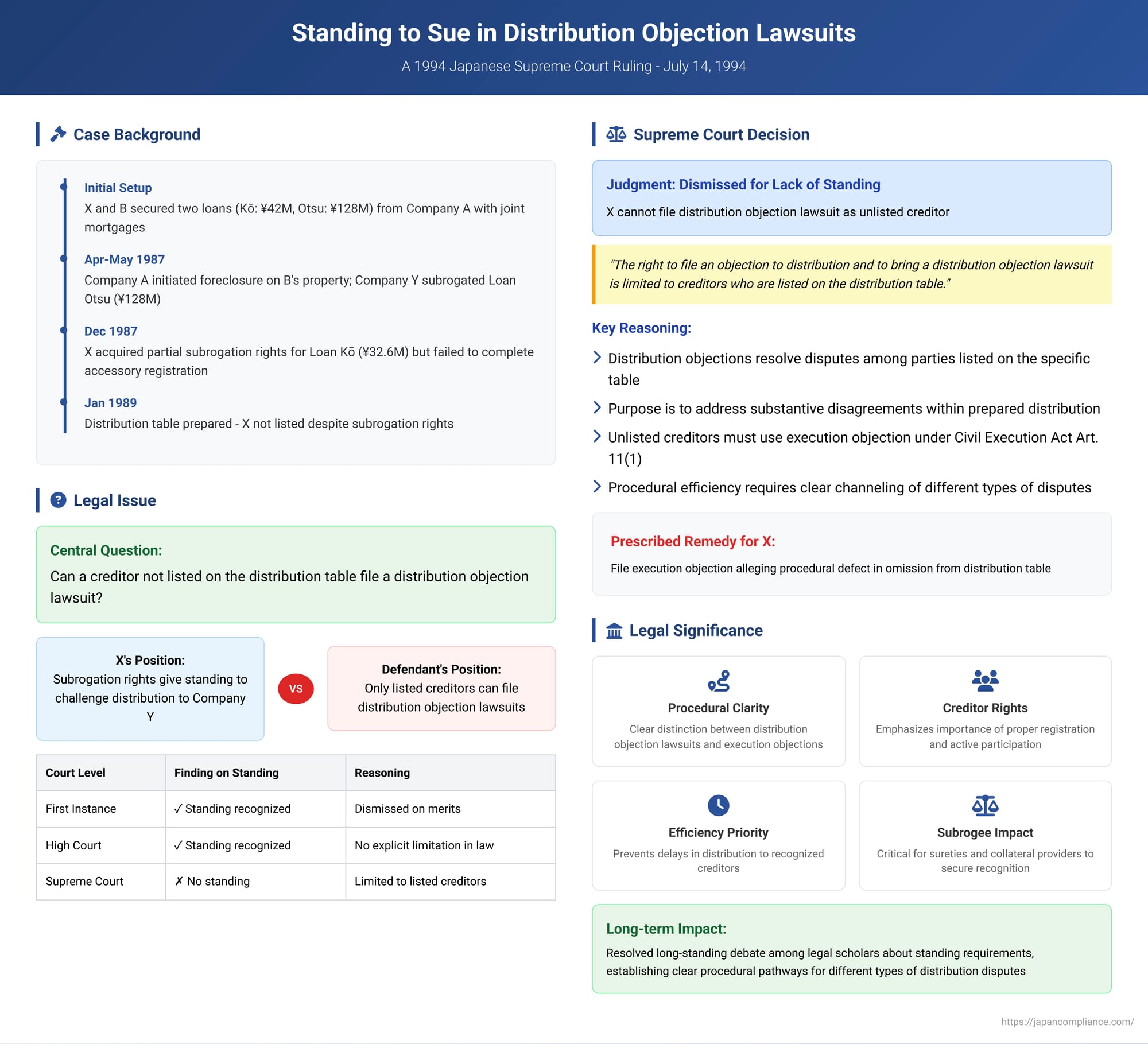

This article examines a key Japanese Supreme Court judgment from July 14, 1994, which clarified who has the legal standing to file a "distribution objection lawsuit" (haitō igi no uttae) in the context of real estate auction proceeds. The decision specifically addresses whether a creditor not listed on the court's distribution table (haitō-hyō) can initiate such a lawsuit.

Factual Background: A Complex Web of Mortgages and Subrogation

The case arose from a complex series of loans, mortgages, and subrogations:

- Original Loans and Joint Mortgages:

- Mr. X (the plaintiff, appellant in the Supreme Court, a surety and property provider) and Mr. B (a principal debtor) had secured two loans from Company A: Loan Kō (JPY 42 million) and Loan Otsu (JPY 128 million).

- To secure these loans, Mr. X and Mr. B established joint mortgages on their respective properties. The mortgage securing Loan Kō (the "Kō Mortgage") had priority over the mortgage securing Loan Otsu (the "Otsu Mortgage").

- Auction of B's Property (The "Main Auction"):

- Company A initiated a foreclosure auction against Mr. B's property based on the Kō Mortgage. An auction commencement decision was made on April 30, 1987, and a seizure registration followed on May 2, 1987.

- Company Y's Involvement:

- Company Y (the defendant, appellee in the Supreme Court) had provided a joint guarantee for Mr. B's Loan Otsu.

- On May 7, 1987, Company Y paid the full amount of Loan Otsu to Company A by way of subrogation (bensai ni yoru daii).

- On June 17, 1987, Company Y acquired Company A's rights under the Otsu Mortgage and completed the accessory registration (fuki tōki) for this transfer.

- X's Subrogation (Prior Separate Auction):

- In a separate auction involving Mr. X's own property (initiated by a different creditor), Company A had participated as a creditor based on the Kō Mortgage and received a partial payment (approximately JPY 32.6 million) from those proceeds according to a distribution table dated December 22, 1987.

- As a result of this partial payment (which Mr. X, as a surety and owner of the collateral, effectively bore), Mr. X acquired by subrogation a portion of Company A's rights under Loan Kō and the associated Kō Mortgage.

- However, crucially, Mr. X had not completed an accessory registration to reflect this partial transfer of the Kō Mortgage to himself.

- Distribution in the Main Auction:

- In the Main Auction (concerning Mr. B's property), Company A filed a claim for the outstanding balance of Loan Kō. Company Y filed a claim for the amount it had paid by subrogation for Loan Otsu.

- On January 11, 1989, the execution court prepared a distribution table for the Main Auction.

- Mr. X was not summoned to the distribution date for the Main Auction and was not listed as a creditor on this distribution table.

- X's Objection and Lawsuit:

- Despite not being listed, Mr. X appeared on the distribution date and lodged an objection concerning the amount allocated to Company Y.

- Subsequently, Mr. X filed the present distribution objection lawsuit, arguing that, due to his subrogation rights regarding Loan Kō, he had priority over Company Y to the extent of his subrogated amount (based on former Civil Code Article 501, Item 5, among other grounds).

The Procedural Hurdle: X's Standing to File a Distribution Objection Lawsuit

The primary legal question before the Supreme Court was whether Mr. X, who was not listed as a creditor on the distribution table, had the requisite legal standing (genkoku tekkaku) to file a distribution objection lawsuit.

Lower Courts' Approach

- First Instance Court: Recognized Mr. X's standing to sue but ultimately dismissed his claim on the merits. It held that Mr. X's subrogated portion of the Kō Mortgage was junior to Company A's remaining portion of the same mortgage.

- High Court: Affirmed the first instance court's decision, also agreeing that Mr. X had standing. The High Court reasoned that Article 89, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Execution Act (which governs who can file an objection) does not explicitly limit this right to creditors listed on the distribution table. It also found no compelling reason to prevent a creditor who acquired rights by subrogation but was omitted from the table from challenging the distribution to other listed creditors.

Mr. X appealed the substantive dismissal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Ruling

On July 14, 1994, the Supreme Court overturned the lower courts' judgments regarding standing and dismissed Mr. X's lawsuit for lack of standing.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Nature of the Distribution Procedure: In real estate auction distribution proceedings, the execution court summons creditors it recognizes as entitled to distribution (Civil Execution Act Art. 87(1)), conducts necessary inquiries, and prepares a distribution table. This table lists each creditor, their claim amount, their priority ranking, and the amount of distribution they are to receive. This distribution is determined either by agreement among all creditors or, in the absence of agreement, by the rules of substantive law (Civil Execution Act Art. 85, via Art. 188).

- Purpose of Distribution Objections and Lawsuits: An objection to distribution (haitō igi no mōshide) and a subsequent distribution objection lawsuit (haitō igi no uttae) are procedures designed to resolve substantive disagreements concerning the claims or distribution amounts as stated in the prepared distribution table. These are mechanisms for resolving disputes individually and relatively among the parties involved in that specific table.

- Standing Limited to Listed Creditors: Therefore, the right to file an objection to distribution and to bring a distribution objection lawsuit is limited to creditors who are listed on the distribution table. A person not listed on the table, even if they believe they are a creditor entitled to distribution, does not have standing to file a distribution objection lawsuit asserting their right to be included or to challenge allocations to others through this specific type of lawsuit.

- Prescribed Remedy for Omission: The Supreme Court clarified that if a creditor believes they are entitled to a distribution but were wrongly omitted from the distribution table, their proper remedy is to file an execution objection (shikkō igi) under Article 11, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Execution Act. This execution objection would allege a procedural defect or illegality in the process of creating the distribution table.

Because Mr. X was not listed as a creditor on the distribution table in the Main Auction, the Supreme Court concluded he lacked standing to bring a distribution objection lawsuit. His suit was therefore deemed improper and was dismissed.

Analysis and Significance

This 1994 Supreme Court decision is a landmark ruling that resolved a long-standing debate among legal scholars and practitioners regarding who can initiate a distribution objection lawsuit.

- Clarification of Procedural Pathways: The judgment clearly distinguishes the procedural remedies:

- A distribution objection lawsuit is for listed creditors to dispute the substantive accuracy (e.g., amounts, priorities) of what is on the table.

- An execution objection is the appropriate channel for a creditor to complain about being omitted from the table, framing it as a procedural error by the execution court.

- Implications for Creditors, Especially Subrogees: The ruling underscores the critical importance for creditors, particularly those who acquire rights by subrogation (like sureties or providers of collateral who make payments), to take active steps to have their rights recognized and be listed on the distribution table. For Mr. X, the failure to complete an accessory registration (fuki tōki) for his subrogated mortgage right likely contributed to his omission by the execution court. While legal commentary suggests that an accessory registration might primarily be necessary for a subrogee to initiate their own foreclosure, and other forms of proof might suffice to assert rights in an ongoing auction, its absence can clearly create practical hurdles in being recognized by the court for distribution.

- Procedural Efficiency vs. Substantive Rights: The Supreme Court's rationale appears to prioritize procedural orderliness and the timely finalization of distributions. Allowing unlisted parties to initiate distribution objection lawsuits could significantly complicate and delay payments to other recognized creditors. The prescribed route of an execution objection is generally a simpler and quicker procedure for the court to address the alleged omission.

- Alternative Recourse (Post-Distribution): If an execution objection fails or is not pursued, a creditor omitted from the distribution table might consider an unjust enrichment claim against those who received distributions they were not entitled to. However, such claims have their own complexities and limitations, as established in other Supreme Court precedents (e.g., the different treatment for general versus secured creditors). The commentary around this case suggests that if the execution objection route is the primary remedy for omission, subsequent unjust enrichment claims might be the ultimate path for substantive recovery if the execution objection is unsuccessful but a substantive right exists.

- Ongoing Debate: While the judgment provides clarity on standing for distribution objection lawsuits, legal scholars continue to debate whether this procedural channeling is always the most effective or fair means of resolving substantive entitlement disputes. Some argue that a distribution objection lawsuit, which directly addresses substantive rights, could be a more straightforward path to a definitive resolution rather than a multi-step process of execution objection potentially followed by an unjust enrichment claim. The efficacy of the execution objection itself for rectifying omissions and ensuring correct substantive distribution has also been questioned.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's July 14, 1994, decision decisively established that only creditors listed on a distribution table have the standing to file a distribution objection lawsuit in Japanese real estate auction proceedings. Creditors who believe they have been wrongly omitted must first challenge the omission itself through an execution objection, alleging a procedural flaw in the table's creation. This ruling emphasizes the importance of active participation and proper registration of rights by creditors to ensure their inclusion in distribution proceedings and clarifies the distinct procedural avenues for challenging perceived errors in the distribution process.