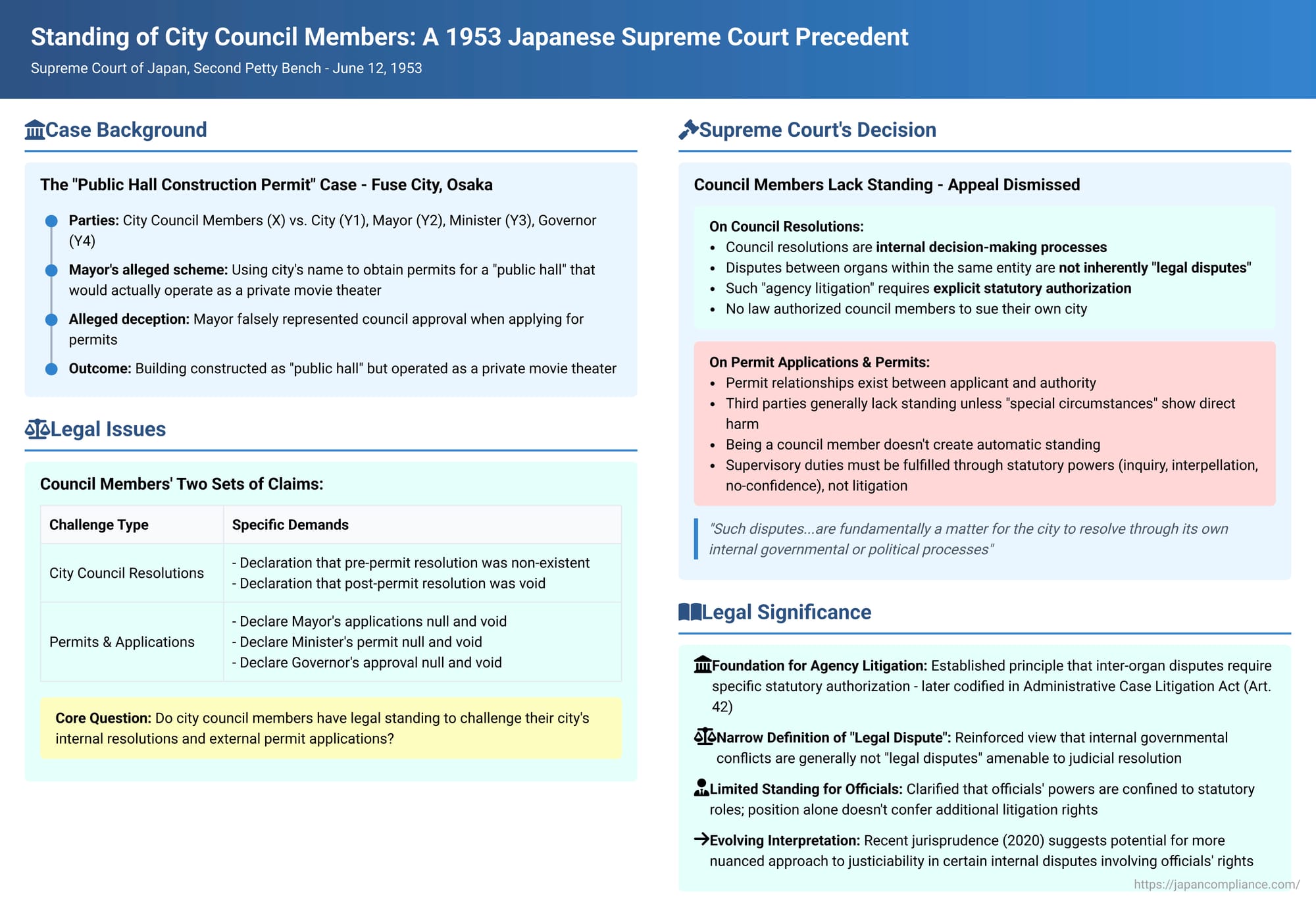

Standing of City Council Members: A 1953 Japanese Supreme Court Precedent on Challenging Municipal Actions and "Agency Litigation"

Date of Judgment: June 12, 1953

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

On June 12, 1953, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a seminal decision in what is known as the Public Hall Construction Permit Nullity Confirmation Request Case. The case involved city council members from the former Fuse City in Osaka Prefecture who sought to challenge a series of municipal actions related to the construction of a public hall. The core issue was the legal standing of these council members, acting in their official capacity, to sue their own city, its mayor, and other state entities to contest the validity of city council resolutions, permit applications made by the city, and permits subsequently granted. This judgment established early and influential principles regarding "agency litigation"—disputes between different organs within the same public entity—and offered a restrictive interpretation of what constitutes a "legal dispute" amenable to judicial resolution, particularly in the era before the enactment of Japan's comprehensive Administrative Case Litigation Act.

I. The Allegations: A Public Hall or a Private Ruse?

The dispute was set in Fuse City, Osaka Prefecture (which later merged with other cities to become part of the present-day Higashiosaka City). The case pitted city council members against their own municipal government and higher state authorities over a contentious construction project.

The Players Involved:

- The plaintiffs, X, were a group of city council members of Fuse City.

- The defendants included Y1 (Fuse City itself), Y2 (the Mayor of Fuse City), Y3 (the national Minister of Construction), and Y4 (the Governor of Osaka Prefecture).

The Project in Question:

The controversy centered around the construction of a purported city public hall. For this project, Y2, the Mayor of Fuse City, had formally applied for and successfully obtained the necessary construction permits and approvals from Y3, the Minister of Construction, and Y4, the Governor of Osaka Prefecture, under the prevailing building regulations of the time (the Temporary Building Restriction Rules and the Urban Area Building Act).

The Council Members' Allegations of Deceit:

The plaintiff council members (X) painted a starkly different picture of the project's origins and execution, alleging a scheme orchestrated by the Mayor. According to X's claims:

- The Mayor (Y2) was aware that a close associate, the representative of a private company, was facing difficulties in obtaining a permit to construct a movie theater.

- To assist this associate, Y2 allegedly conceived a plan to use the city's name and authority to obtain construction permits for a "city public hall" on the land where the associate had intended to build the movie theater.

- Crucially, Y2 allegedly proceeded to apply for these permits by falsely representing to the higher authorities (Y3 and Y4) that the Fuse City Council had duly approved the public hall project. X contended that, at the time of these applications, the matter had not even been formally presented to or deliberated by the city council.

- Subsequently, in an effort to create an appearance of legitimacy and provide an ex post facto justification for the project, Y2 submitted a budget proposal and other necessary motions related to the public hall construction to the city council. The council, X alleged, approved these measures despite being aware, or at least suspecting, the underlying deceptive intent of the Mayor's actions.

- The deception allegedly continued even after the "public hall" was completed and an opening ceremony was held. According to X, Y2 then manipulated the city council into passing a resolution that approved a "settlement agreement" between Fuse City and the associate's private company concerning the newly constructed building.

- The purported outcome of this agreement was that the building, officially permitted and constructed as a city public hall, effectively fell under the control of the private company and was subsequently operated as a movie theater, fulfilling the associate's original commercial objective.

II. The Legal Challenge by Council Members

Acting in their stated capacity as members of the Fuse City Council, X initiated legal proceedings against Fuse City (Y1), its Mayor (Y2), the Minister of Construction (Y3), and the Governor of Osaka Prefecture (Y4). Their lawsuit presented two distinct sets of demands for judicial declarations:

- Challenges to Permit Applications and Permits (Against Y1, Y2, Y3, and Y4):

- A declaration that Mayor Y2's applications to the Minister Y3 and Governor Y4 for the construction permits and approvals were null and void.

- A declaration that the construction permit issued by Minister Y3 was null and void.

- A declaration that the approval (related to the permit process) granted by Governor Y4 was null and void.

- Challenges to City Council Resolutions (Against Y1 and Y2):

- A declaration that the alleged Fuse City Council resolution, which Y2 supposedly relied upon before applying for the permits, was in fact non-existent (i.e., had never actually been passed).

- A declaration that the Fuse City Council resolution passed after the construction permit had been obtained (which X likely contended was the resolution approving the "settlement agreement" with the private company) was null and void.

Lower Court Rulings:

X's lawsuit did not succeed in the lower courts. Both the Osaka District Court, acting as the court of first instance, and subsequently the Osaka High Court, on appeal, dismissed all of X's claims. The consistent reasoning of these lower courts was that X, even as city council members, lacked the necessary legal standing or a cognizable legal interest to bring such lawsuits against the city, its mayor, or the state authorities involved in the permitting process. Following these dismissals, X appealed their case to the Supreme Court of Japan.

III. The Supreme Court's Judgment: Demarcating Internal Affairs from Justiciable Disputes

The Supreme Court, in its decision of June 12, 1953, affirmed the judgments of the lower courts and dismissed X's appeal. The Court's reasoning carefully distinguished between the nature of X's challenge to the city council resolutions and their challenge to the permit applications and the permits themselves.

A. Regarding Challenges to City Council Resolutions (Claim 2)

- Nature of Council Resolutions: The Supreme Court began by observing that a resolution passed by a city council is, in essence, an internal decision-making process of the municipal corporation (in this case, Fuse City). Such a resolution, by itself, does not create direct legal effects or obligations for external third parties; rather, it guides the actions of the city's executive organs. Consequently, the Court viewed the act of suing the city to confirm the non-existence or invalidity of such an internal resolution as "meaningless" in terms of seeking a direct legal remedy against an external act.

- Council Members' Standing for Internal Disputes: X had argued that their status as members of the Fuse City Council endowed them with a special legal interest in seeking judicial confirmation regarding the validity of council resolutions. The Supreme Court acknowledged the constitutional and statutory principle that the mayor (the executive organ) is bound by the legitimate resolutions of the city council (the legislative organ). However, the Court fundamentally characterized the relationship between the executive and legislative branches within a municipality as an internal relationship between different organs or components of the same single municipal entity.

- Internal Disputes Are Not Inherently "Legal Disputes": Drawing from this characterization, the Court articulated a crucial principle: if a conflict or dispute arises between such internal organs concerning their respective powers or the validity of their actions vis-à-vis each other, it is fundamentally a matter for the city to resolve through its own internal governmental or political processes. Such disputes, the Court stated, are not inherently "legal disputes" (hōritsu-jō no sōsō) that are automatically subject to adjudication by the courts. This is because disputes over the powers and competences of organs within the same legal entity (like a city) are qualitatively different from disputes over legal rights and duties that arise between distinct and separate legal personalities (e.g., between two individuals, two corporations, or an individual and the state acting as a distinct legal person).

- Requirement of Specific Statutory Authorization for Inter-Organ Lawsuits: The Supreme Court held that lawsuits concerning internal disputes between governmental organs about their powers or decisions could only be brought before a court if a specific law expressly permitted such litigation. The Court provided an example by referencing Article 176, paragraph 5 of the Local Autonomy Act (as it existed then), which allowed for certain types of legal challenges by a mayor or governor concerning council resolutions, or conversely, by the council concerning certain executive actions, under specified conditions. The PDF commentary explains that this type of litigation, involving disputes between organs of the same public entity, is known as "agency litigation" (kikan soshō). The commentary underscores the significance of this 1953 Supreme Court judgment in judicially endorsing the view that such agency litigation requires specific statutory authorization to be admissible. This principle was later formally enshrined in the Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA), which was enacted after this judgment. The ACLA, in Article 6, defines agency litigation and, in Article 42, stipulates that such litigation can only be initiated "when prescribed by law, and only by such persons as are prescribed by such law".

- No Authorization for the Present Suit by Council Members: Applying this principle, the Supreme Court found no provision in the Local Autonomy Act or any other existing law that would authorize city council members to sue their own city or its mayor to seek a judicial declaration concerning the non-existence or invalidity of a city council resolution. In the absence of such specific statutory authorization, the Court concluded that the lower courts were correct in deeming this part of X's lawsuit (Claim 2) inadmissible.

B. Regarding Challenges to Permit Applications and Permits (Claim 1)

- Legal Nature of Permit Applications: The Court then turned to X's claims concerning the invalidity of the mayor's applications for permits and the permits/approvals themselves. It reasoned that any legal relationship that arises from an application for a permit (e.g., when the Mayor of Fuse City applied to the Minister of Construction) is primarily a legal relationship between the applicant (Fuse City, acting through its executive, the Mayor) and the relevant permitting authority (the Minister or the Governor). As a general rule, third parties—those not directly involved as applicant or permitter—do not have a direct legal interest or stake in this application process itself. Consequently, such third parties typically lack the legal standing to initiate a lawsuit to contest the validity of such an application.

- Standing to Challenge Permits and Approvals: The Supreme Court extended similar reasoning to the actual permits or approvals granted by the authorities. Generally, third parties do not possess the legal standing to challenge the validity of a permit or approval issued to another party. An exception to this general rule exists if there are "special circumstances" under which a third party's own distinct legal interests are directly and unlawfully harmed by the issuance of the permit. In the present case, X, the council members, had not alleged any such special circumstances demonstrating that their personal legal interests, separate and distinct from their roles as council members or general citizens, were directly infringed by the permits.

- Effect of Status as Council Member or Resident: X had strongly argued that their status as members of the Fuse City Council inherently provided them with the necessary legal interest to challenge these applications and permits on behalf of the public or the city's proper governance. The Supreme Court rejected this line of argument. It stated that while city council members do indeed participate in the city's decision-making processes as constituent members of the legislative organ (with powers and duties defined by the Local Autonomy Act and other relevant laws), their legally cognizable actions and powers as council members are confined to those prescribed by these statutes. Beyond these statutorily defined roles (such as participating in debates, voting on resolutions, scrutinizing budgets, etc.), the mere fact of being a council member does not automatically place them in a different legal position from that of ordinary citizens with respect to their general ability to initiate lawsuits challenging such administrative acts as the granting of permits. Similarly, the Court added, merely being a resident of the city does not, in itself, confer a general standing upon an individual to contest the validity of the city's actions or the permits it receives or that are granted within its territorial jurisdiction.

- Duty of Supervision by Council Members: X also contended that, as city council members, they had a civic and legal duty to supervise the mayor's execution of administrative functions and to ensure the lawfulness of municipal governance, implying that this duty should ground their standing to sue. The Supreme Court countered that such supervisory duties of council members should be fulfilled through the exercise of the specific powers and procedures explicitly granted to them by the Local Autonomy Act and other laws (e.g., powers of inquiry, interpellation, proposing no-confidence motions, budgetary oversight, etc.). The existence of such a general duty of supervision, the Court concluded, does not automatically translate into, or create, a legal standing to initiate lawsuits of this nature.

IV. Understanding "Agency Litigation" and "Legal Disputes"

The PDF commentary accompanying the case text provides indispensable context for appreciating the broader legal significance of this 1953 Supreme Court decision, particularly in its treatment of what is known in Japanese administrative law as "agency litigation" and its application of the concept of a "legal dispute."

- Agency Litigation (kikan soshō): X's attempt, as city council members, to sue their own city and its mayor regarding the validity or existence of city council resolutions (Claim 2 in their lawsuit) is a quintessential example of what Japanese legal doctrine terms "agency litigation" (kikan soshō). This category of litigation refers specifically to disputes that arise between different organs or constituent components within the same single public administrative entity—in this case, between members of the legislative council on one hand, and the executive mayor (and the city as a whole) on the other, all operating within the legal framework of Fuse City. The Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA), which was enacted some years after this Supreme Court judgment, formally defines agency litigation in its Article 6 as "disputes concerning the existence or exercise of competence between organs of the State or a public entity".

- "Legal Disputes" (hōritsu-jō no sōsō) and the Scope of Justiciability: A foundational principle of the Japanese judicial system, derived from Article 3, paragraph 1 of the Court Act, is that the courts have jurisdiction to adjudicate only "all legal disputes." The Supreme Court, in this 1953 ruling concerning the Fuse City public hall, effectively affirmed what was already a traditional understanding in Japanese administrative law: that disputes purely between state organs regarding their powers and competences are not inherently "legal disputes" in the sense required for judicial intervention. Such conflicts are often viewed as internal administrative or political matters that should, in the first instance, be resolved within the administrative framework itself or through political processes, unless a specific statute exceptionally carves out a role for the courts. The underlying rationale for this restrictive view is often that administrative organs, unlike individuals or private corporations, are not typically considered to be bearers of subjective rights in their interrelations; their conflicts usually pertain to spheres of authority, competence, or the proper interpretation of their duties. Litigation concerning such matters, even when permitted by statute, often serves the objective of ensuring the overall legality and proper functioning of the administrative legal order (an "objective" purpose) rather than primarily protecting individual rights (a "subjective" purpose).

- The ACLA's Codification of a Restrictive Approach: The Administrative Case Litigation Act, in its Article 42, subsequently codified this traditionally restrictive approach to agency litigation by stipulating that such litigation "may be filed only in cases prescribed by law and only by such persons as are prescribed by such law". This provision effectively prohibits agency litigation unless there is explicit, specific statutory authorization for a particular type of inter-organ dispute to be brought before the courts, and then only by the organ or person designated in that statute.

- The General Definition of a "Legal Dispute": Generally, for a matter to be considered a "legal dispute" justiciable by Japanese courts, it is understood that two core conditions must be satisfied, as articulated in other Supreme Court precedents (e.g., a 1981 Supreme Court case referenced in the commentary):

- The matter must constitute a concrete dispute between specific parties concerning the existence or non-existence of particular legal relationships or specific rights and duties (this is often referred to as the requirement of "concreteness" or "case-or-controversy" like character).

- The dispute must be capable of being definitively resolved through the application of existing law by a court (this is the requirement of "legal resolvability").

While X's claims in the Fuse City case might, on a superficial reading, appear to involve concrete disagreements and questions of law, the traditional interpretation, particularly as applied to inter-organ disputes and upheld in this 1953 judgment, often excluded them from the category of "legal disputes." This was largely based on the premise that internal governmental organs do not typically possess "rights" against each other in the same manner that private parties do; their disputes are more about power and jurisdiction.

V. Evolving Perspectives and the Legacy of the 1953 Ruling

While the 1953 Supreme Court decision in the Fuse City case has long stood as a key precedent defining the restrictive approach to agency litigation and the justiciability of internal governmental disputes, legal scholarship and judicial thinking in Japan have not remained static. The PDF commentary accompanying this case points to more recent trends, academic critiques, and even subsequent Supreme Court case law that suggest a potential for a more expansive understanding of what may constitute a "legal dispute" amenable to judicial review.

- Critique of Traditional Dichotomies: Many contemporary legal scholars in Japan have voiced criticisms of a rigid equation of "legal dispute" solely with "subjective litigation" (i.e., litigation that is exclusively aimed at the protection of an individual's private rights). They argue that such a strict dichotomy can unduly limit access to justice and may prevent courts from resolving genuinely concrete disputes that are perfectly amenable to legal resolution, even if those disputes don't fit neatly into the traditional mold of redressing an individual's rights violation. Some scholars propose a more nuanced, concentric-circle model of judicial power, envisioning a core area of disputes that courts are constitutionally mandated to hear, an outer boundary beyond which courts cannot venture, and an intermediate zone where the appropriateness of judicial review might depend on evolving legislative policy and the specific nature of the dispute itself.

- Potential for Broader Interpretation of "Legal Dispute": There is a growing argument that even disputes that formally involve administrative organs might qualify as "legal disputes" if those organs can demonstrate a unique, judicially protectable status or a specific, cognizable interest that is being infringed. Some legal theorists also contend that the ACLA's restrictive definition of agency litigation should perhaps be primarily applied to disputes concerning competence within the same single administrative entity, and that disputes between formally distinct administrative organs might still be considered justiciable if they otherwise meet the broader, more general criteria of a "legal dispute".

- Impact of More Recent Supreme Court Case Law: A particularly significant development highlighted in the PDF commentary is a Supreme Court Grand Bench decision from November 25, 2020. In that relatively recent case, the Supreme Court held that a disciplinary action (specifically, a suspension from attending assembly sessions) taken by a local assembly against one of its own members was indeed subject to judicial review. The Court's reasoning in the 2020 case emphasized that such a suspension directly restricts the disciplined member's ability to perform their essential duties, which include participating in assembly debates and exercising their voting rights. A supplementary opinion by one of the justices in that 2020 case further affirmed the "legal dispute" nature of the claim by directly applying the general two-pronged criteria for justiciability (concreteness and legal resolvability), without getting entangled in the traditional subjective/objective litigation dichotomy. This opinion explicitly recognized the rights-based aspect of a council member's ability to participate in assembly proceedings.

- Future Outlook on the 1953 Precedent: This more recent jurisprudence from the Supreme Court suggests that the very strict limitations on justiciability for matters involving internal governmental processes or the status and functions of their members, as exemplified by the 1953 Fuse City ruling, might be subject to ongoing re-evaluation and refinement. The PDF commentary thoughtfully concludes by suggesting that future developments in case law, especially if they continue to adopt a more direct and less formulaic approach to defining what constitutes a "legal dispute," could potentially narrow the effective scope and influence of the principles laid down in the 1953 Fuse City judgment.

VI. Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's 1953 decision in the Fuse City public hall construction case remains a significant historical landmark in the nation's administrative law. It is particularly noted for its early and clear articulation of the principles that would govern "agency litigation" and for defining the then-prevailing narrow scope of legal standing for public officials, such as city council members, when they sought to challenge internal municipal decisions or related administrative actions through the courts.

By largely restricting such lawsuits to instances where specific statutory authorization existed, the Court reinforced the view that internal governmental disputes were generally not considered "legal disputes" ripe for judicial resolution. This stance, emphasizing internal resolution mechanisms for inter-organ conflicts, was later formally codified in the Administrative Case Litigation Act.

However, while foundational, the strict jurisprudential approach evident in this mid-20th century ruling is now viewed within the broader context of evolving legal theories and more recent Supreme Court decisions. These later developments indicate a judicial willingness to examine the justiciability of claims involving governmental bodies and their members with a greater focus on the specific rights and legally protected interests at stake, potentially signaling a gradual, though cautious, shift in the landscape of administrative litigation and access to courts in Japan.