Squeezed Out: Who Can Challenge the Price? A Japanese Supreme Court Decision on Shareholder Appraisal Rights

Judgment Date: August 30, 2017

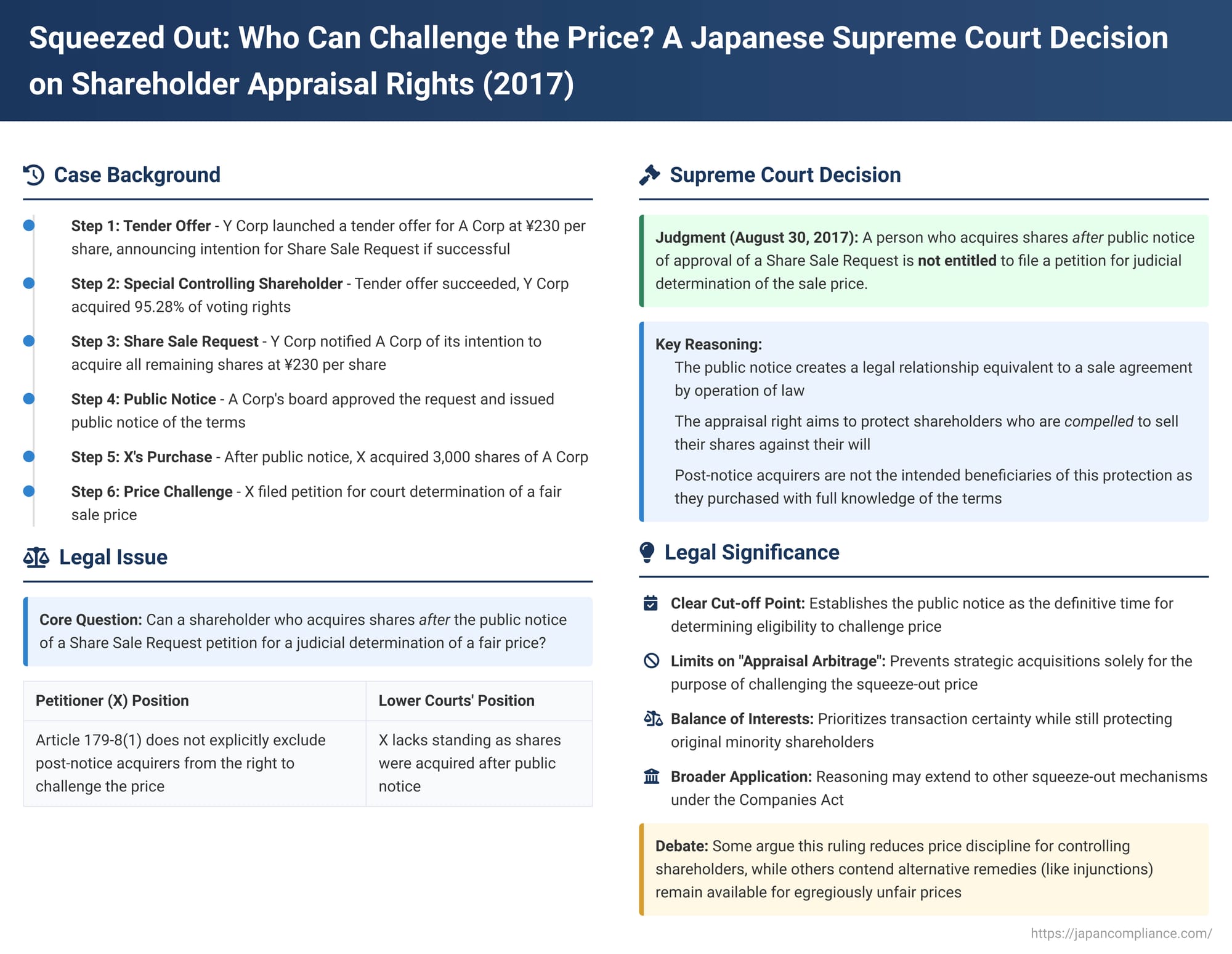

When a company acquires a supermajority stake in another, Japanese corporate law provides mechanisms for the acquirer to obtain 100% ownership by "squeezing out" the remaining minority shareholders. One such mechanism is the "Share Sale Request" (株式売渡請求 - kabushiki uriwatashi seikyū) by a "special controlling shareholder." While this process forces minority shareholders to sell their shares, the law also grants them a right to petition a court for a determination of a fair sale price if they are dissatisfied with the price offered by the acquirer. A key question, however, is who precisely qualifies to exercise this appraisal right. Specifically, can a shareholder who acquires shares after the public announcement of the squeeze-out terms still challenge the offered price? A 2017 Supreme Court of Japan decision provided a definitive answer.

The Mechanics of a Share Sale Request: A Two-Step Squeeze-Out

The case arose from a typical two-step acquisition process aimed at taking a publicly traded company private. Y Corp sought to make A Corp its wholly-owned subsidiary.

- Tender Offer: Y Corp first launched a public tender offer for all shares of A Corp at a price of ¥230 per share. In its public announcement for the tender offer, Y Corp also disclosed its intention, should the tender offer be successful but not result in 100% ownership, to utilize the Share Sale Request mechanism under Article 179 of the Companies Act. This request would be to acquire all remaining A Corp shares at the same price as the tender offer (¥230 per share), provided Y Corp secured 90% or more of A Corp's total voting rights through the tender offer.

- Becoming a Special Controlling Shareholder: The tender offer was successful, and Y Corp acquired 95.28% of A Corp's voting rights. This made Y Corp a "special controlling shareholder" as defined in Article 179, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act.

- Initiating the Share Sale Request: Subsequently, Y Corp formally notified A Corp (the target company) of its intention to make a Share Sale Request to all remaining shareholders of A Corp. This notice included the legally required details, such as the price of ¥230 per share to be paid for the shares (as per Article 179-2, Paragraph 1 and Article 179-3, Paragraph 1).

- Target Company Approval and Public Notice: A Corp's board of directors convened and passed a resolution approving Y Corp's Share Sale Request. Following this approval, A Corp made a public notice (本件公告 - honken kōkoku) as required by law (Article 179-4, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Companies Act, and Article 161, Paragraph 2 of the Act on Book-Entry Transfer of Company Bonds, Shares, etc.). This public notice detailed the board's approval, the acquisition price (¥230 per share), the planned acquisition date, and other pertinent information for the "selling shareholders" (uriwatashi kabunushi – those whose shares were subject to the request).

The Legal Challenge: Standing to Demand a Fair Price

The petitioner, X, entered the scene after A Corp had made this crucial public notice. X acquired 3,000 shares of A Corp (which were now designated as "shares to be sold" or uriwatashi kabushiki under the request). Dissatisfied with the ¥230 per share price determined by Y Corp, X filed a petition with the Nagano District Court pursuant to Article 179-8, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act, asking the court to determine a fair sale price for the shares.

Both the District Court and, subsequently, the Tokyo High Court on appeal, ruled X's petition inadmissible. Their reasoning was that X lacked standing to file such a petition because X had acquired the shares after A Corp's public notice regarding the Share Sale Request. X then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing that Article 179-8, Paragraph 1, which grants the right to file a price determination petition to "selling shareholders," does not explicitly exclude those who acquire shares after the public notice.

The Supreme Court's Decision: A Clear Cut-Off Point

The Supreme Court, in its decision dated August 30, 2017, dismissed X's appeal, thereby affirming the lower courts' stance. The Court provided a clear interpretation of who is eligible to file for a price determination in the context of a Share Sale Request.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Automatic Legal Effect of Public Notice: The Court first emphasized the legal effect of the Share Sale Request process. Once the special controlling shareholder (Y Corp) makes the request, the target company's board (A Corp) approves it, and this approval, along with the terms (like price and acquisition date), is publicly announced or notified to the selling shareholders (as per Article 179-4, Paragraph 1, Item 1), a significant legal change occurs. This process creates, by operation of law and without requiring the individual consent of each selling shareholder, a legal relationship equivalent to a sale and purchase agreement for the shares between the special controlling shareholder and the selling shareholders (Article 179-4, Paragraph 3). The special controlling shareholder then automatically acquires all the targeted shares on the specified acquisition date (Article 179-9, Paragraph 1).

- Purpose of the Price Determination Right (Appraisal Right): The Supreme Court then articulated its understanding of the legislative intent behind Article 179-8, Paragraph 1, which allows for the price determination petition. It stated that the purpose of this provision is to provide an opportunity to obtain a fair price for those shareholders of the target company who, as of the time of the aforementioned notice or public announcement, find themselves compelled to sell their shares at the stipulated price against their will.

- Post-Notice Acquirers Not the Intended Beneficiaries: Flowing from this purpose, the Court concluded that individuals who acquire shares after the notice or public announcement – that is, after the obligation for those shares to be sold at the set price has become definitive – are not considered to be the intended beneficiaries of the protection offered by Article 179-8, Paragraph 1.

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that a person who acquires shares after the target company's public notice or notification concerning the approval of a Share Sale Request is not entitled to file a petition for a judicial determination of the sale price. Since X had acquired the A Corp shares after A Corp's public notice, X lacked the standing to file such a petition.

Unpacking the Rationale and Its Implications

This Supreme Court decision effectively draws a line in the sand, restricting the right to seek a judicial price appraisal in a Share Sale Request squeeze-out.

- Defining the "Selling Shareholder" for Appraisal Purposes: Article 179-2, Paragraph 1, Item 2 of the Companies Act defines a "selling shareholder" as "a shareholder who sells shares of the target company owned by such shareholder pursuant to a Share Sale Request." A literal reading might suggest that anyone who holds shares at the moment they are transferred to the special controlling shareholder (the acquisition date) is a "selling shareholder." However, the Supreme Court adopted a more restrictive interpretation for the specific purpose of who can file a price determination petition under Article 179-8(1). It focused on the status and knowledge of the shareholder at the time the terms of the forced sale become fixed and public.

- The Significance of the Public Notice: The public notice by the target company (A Corp in this case) following its board's approval of the Share Sale Request is the determinative event. This notice makes the terms of the squeeze-out, including the price, externally clear and establishes the legal framework for the compulsory sale. The Supreme Court views this as the point at which the obligation to sell crystallizes for the shares in question.

- The "Compelled Against Their Will" Rationale: The core of the Supreme Court's reasoning is that the appraisal right is designed to protect shareholders who are being forced to part with their shares at a price they did not agree to and who were holding those shares before this forced sale mechanism was irrevocably set in motion by the public notice. Those who purchase shares after this point are deemed to be doing so with full knowledge of the impending compulsory sale and the offered price. Their acquisition is seen as a voluntary entry into a situation with known terms, rather than an involuntary imposition of those terms.

The Debate: Should Post-Notice Acquirers Have Appraisal Rights?

The Supreme Court's decision, while providing clarity, touches upon a broader debate about the scope and purpose of appraisal rights in squeeze-outs.

- Arguments for Allowing Post-Notice Acquirers to Petition:

- Creating a Market for Appraisal Rights: Allowing post-notice acquisitions by entities willing to litigate could benefit original shareholders, especially small or less sophisticated investors. These original shareholders might lack the resources, time, or expertise to pursue a price determination themselves. They could potentially sell their shares to a specialist (an "appraisal arbitrageur") at a price higher than the squeeze-out offer but lower than the anticipated judicially determined fair value, thus realizing some upside without incurring litigation costs.

- Deterrent Effect on Acquirers: The possibility of post-notice acquirers challenging the price could act as a stronger deterrent against special controlling shareholders offering an unfairly low price in the first place. If any buyer in the market can scrutinize and challenge the price, the acquirer might be more inclined to offer a fair value from the outset.

- Arguments Against Allowing Post-Notice Acquirers (Supporting the Court's View):

- Informed Choice: Buyers who acquire shares after the public notice are fully aware of the squeeze-out terms and the offered price. Their decision to purchase can be seen as an acceptance of these conditions or, at least, the associated risk profile.

- Alternative Remedies: Japanese company law provides other (though perhaps more limited) avenues to challenge a squeeze-out price if it is grossly unfair, such as seeking an injunction to stop the share acquisition (Article 179-7, Paragraph 1, Item 3) or, potentially, filing a lawsuit for the nullity of the share acquisition (Article 846-2, Paragraph 1). Some argue these mechanisms reduce the need to extend appraisal rights to post-notice acquirers specifically for deterrent purposes. However, if the bar for an injunction ("grossly unfair") is high, the price determination petition remains crucial for ensuring a "fair" price that may not be grossly unfair but still inadequate.

Broader Scope: Implications for Other Squeeze-Out Mechanisms

While this Supreme Court decision directly pertains to the Share Sale Request mechanism under Article 179, its logic may have implications for other squeeze-out methods available under the Companies Act. These include:

- Acquisition of Shares with Class-Wide Call Provisions (Article 171): Where a company acquires all shares of a certain class.

- Share Consolidations (Article 180): Which can be structured to leave minority shareholders with fractional shares that are then cashed out.

Both of these methods also trigger rights for dissenting shareholders to demand that the company purchase their shares at a fair price, and if no agreement is reached, to petition a court for a price determination (Article 172 for class shares subject to call; Article 182-4 for share consolidations).

Legal commentators suggest that the Supreme Court's reasoning in the 2017 Share Sale Request case – particularly its emphasis on the point at which the obligation to sell at a set price becomes definitive and externally clear – might be extended to these other scenarios. If so, shareholders who acquire shares after the shareholder meeting resolution approving such actions (which also sets the terms and price) might similarly be barred from petitioning for a price determination.

However, a nuanced interpretation might consider that the Supreme Court in the 2017 decision also emphasized that the terms became "externally clear" through the public notice. A shareholder resolution, by itself, might not always be considered "externally clear" to the entire market until it is formally announced or notified more broadly. Thus, the critical cut-off point in these other squeeze-out methods could arguably be the public announcement or official notification of the shareholder resolution, rather than the mere passing of the resolution itself.

Conclusion

The August 30, 2017, Supreme Court decision establishes a clear rule for Share Sale Request squeeze-outs: the right to petition a court for a determination of a fair sale price is reserved for those individuals who were shareholders at the time the target company publicly announced its board's approval of the squeeze-out terms. Shareholders who purchase shares after this point, with knowledge of the impending compulsory sale and its terms, are not eligible for this specific judicial price review. This ruling prioritizes a particular understanding of which shareholders are "compelled" to sell against their will and are thus the intended beneficiaries of this statutory protection, providing important guidance for participants in Japanese M&A transactions.