"Springing" Security in Bankruptcy: A 2004 Japanese Supreme Court Decision on Conditional Claim Assignments

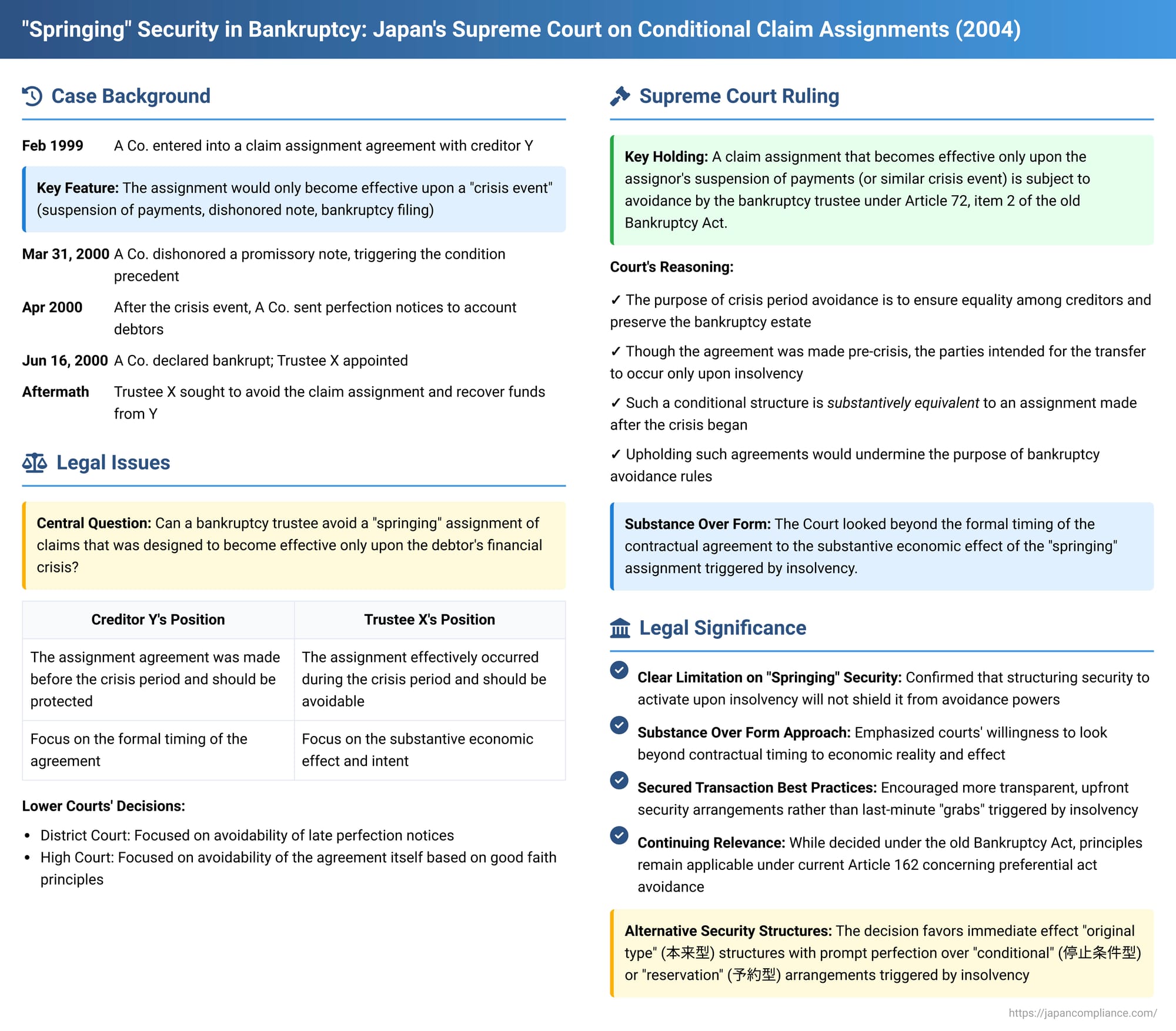

In the world of secured financing, parties sometimes structure agreements where a security interest, though arranged in advance, only becomes fully effective upon the occurrence of a future "triggering event," often linked to the debtor's financial distress. These are sometimes referred to as "springing" security interests. A critical question in Japanese bankruptcy law has been whether such an arrangement, particularly a comprehensive assignment of a company's present and future accounts receivable that "springs" into effect when the company suspends payments or files for bankruptcy, can be avoided by the company's subsequent bankruptcy trustee. On July 16, 2004, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan provided a definitive answer, holding that such assignments are indeed avoidable.

Factual Background: The Conditional "Springing" Assignment

The case involved A Co., a company engaged in steel sales. In February 1999, A Co. entered into a comprehensive claim assignment agreement with Y, a creditor. Under this agreement, A Co. agreed to assign all its present and future accounts receivable from certain specified third-party debtors to Y as security for all of A Co.'s outstanding and future debts to Y.

The crucial feature of this agreement was a condition precedent (停止条件 - teishi jōken): the assignment of the claims would only take effect if A Co. experienced a "crisis event." These trigger events were defined to include A Co. filing a petition for bankruptcy proceedings, entering a state of "suspension of payments" (支払停止 - shiharai teishi, a key indicator of insolvency), or having one of its promissory notes dishonored.

On March 31, 2000, A Co. did, in fact, dishonor a promissory note, thereby triggering the condition precedent and causing it to enter a state of suspension of payments. Subsequently, from April 3, 2000, onwards—i.e., after the crisis event had occurred—A Co. took steps to perfect the claim assignment by sending notices, bearing a certified date (確定日付 - kakutei hizuke), to the relevant third-party account debtors, informing them of the assignment to Y.

A few months later, on June 16, 2000, A Co. was formally declared bankrupt under Japan's (then) old Bankruptcy Act. X was appointed as A Co.'s bankruptcy trustee. Trustee X then initiated legal proceedings against Y. X sought to avoid the entire claim assignment that had "sprung" into effect upon A Co.'s suspension of payments, arguing it was an avoidable transaction under either Article 72, item 1 (intentional fraudulent act avoidance) or item 2 (crisis period avoidance) of the old Bankruptcy Act. X also sought to avoid the perfection notices sent after the suspension of payments, under Article 74, item 1 of the old Act (avoidance of perfection acts). The trustee demanded the return of any monies Y had already collected from the assigned accounts receivable and a judicial declaration that any uncollected assigned claims rightfully belonged to the bankruptcy estate (represented by X).

The Nagoya District Court (first instance) largely ruled in favor of trustee X. It specifically found the perfection notices (sent after the suspension of payments) to be avoidable. It reasoned that a 15-day safe harbor period mentioned in Article 74 for perfecting transactions should, in spirit, be calculated from the date the original assignment contract was made (February 1999), not from the much later date when the condition precedent (suspension of payments in March/April 2000) was met.

On appeal, the Nagoya High Court also dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the avoidability of the transaction, but it added a different layer of reasoning. The High Court opined that the claim assignment agreement itself could be avoided by analogy to Article 72, item 1 or 2, based on the principle of good faith. It reasoned that both A Co. and Y knew, at the time they entered into the conditional assignment contract in 1999, that if and when the assignment actually took effect (i.e., upon A Co.'s financial crisis), it would inevitably harm A Co.'s general unsecured creditors. Y then petitioned the Supreme Court for acceptance of its appeal.

The Legal Challenge: Avoiding an Assignment Triggered by Insolvency

Conditional "springing" assignments like the one in this case pose a distinct challenge to bankruptcy avoidance rules. The agreement itself is often concluded when the debtor might still be solvent or not yet in an undeniable state of crisis. However, it is specifically designed to transfer valuable assets (like accounts receivable) to a particular secured creditor at the very moment the debtor's financial collapse becomes manifest (e.g., upon suspension of payments or a bankruptcy filing).

This structure attempts to navigate around typical "crisis period" avoidance rules (such as Article 72, item 2 of the old Bankruptcy Act, now generally covered by preferential act avoidance rules in Article 162 of the current Bankruptcy Act). These rules primarily target detrimental acts performed by the debtor after the crisis period has begun. If the assignment only "springs" into effect at the crisis, but the agreement was made earlier, it creates an argument that the critical "act" of assignment wasn't performed during the vulnerable crisis period itself.

Before this Supreme Court decision, various legal theories had been proposed to address such arrangements, with some arguing that there was no new "act by the bankrupt" to avoid at the moment the condition was met (as the effect was seen as automatic based on the prior contract), while others sought to challenge these arrangements by focusing on the avoidance of the late perfection acts (the notices) or by invoking broader principles like good faith or the doctrine of acts in circumvention of the law.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Substance Over Form – Springing Assignment Avoidable

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of July 16, 2004, dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the lower courts' conclusion that the assignment was avoidable by trustee X. However, the Supreme Court provided its own clear and direct reasoning, focusing on the substantive nature of the conditional assignment itself under Article 72, item 2, of the old Bankruptcy Act.

The Court held that: A claim assignment, which is structured under a contract to become effective only upon the assignor's suspension of payments or similar crisis event (a condition precedent), is subject to avoidance by the assignor's bankruptcy trustee under Article 72, item 2, of the old Bankruptcy Act (crisis period avoidance).

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Purpose of Crisis Period Avoidance: The Court began by explaining the purpose of Article 72, item 2, of the old Bankruptcy Act. This provision designated the period from the debtor's suspension of payments or bankruptcy petition onwards as the debtor's "crisis period." It made acts such as providing security, extinguishing debts, or other acts detrimental to creditors, if performed by the debtor during this crisis period, subject to avoidance. The underlying legislative intent was to ensure equality among creditors and to preserve and augment the bankruptcy estate by nullifying such last-minute actions that could unfairly deplete assets.

- Intent and Effect of Conditional Springing Assignments: The Court then analyzed the nature of a claim assignment agreement where the effectiveness of the assignment is explicitly made conditional upon the assignor (debtor) entering such a crisis period (e.g., suspending payments). Although the contractual agreement itself is concluded before the crisis period begins, the parties to such a contract specifically intend for the actual transfer of the claims (which, until the crisis, remain part of the assignor's general assets available to all creditors) to occur immediately upon the advent of that crisis. The clear objective is to remove these claims from the debtor's general pool of assets and vest them in the specific assignee precisely when the debtor's financial collapse becomes evident.

- Substantive Equivalence to a Post-Crisis Act: The Supreme Court looked at the substantive economic reality and purpose of such a conditional "springing" assignment. It concluded that such an arrangement is, in its content and objective, designed to circumvent the very purpose of Article 72, item 2, and would undermine its effectiveness if upheld. The Court found that, when viewed substantively, a claim assignment that is contractually engineered to take effect only when the debtor enters a state of financial crisis (like suspension of payments) is tantamount to, and should be treated as equivalent to, a claim assignment that was actually made after the debtor had already entered that crisis period.

- Conclusion on Avoidability: Therefore, the Supreme Court held that such a conditionally effective "springing" claim assignment falls within the scope of acts that can be avoided by the bankruptcy trustee under the crisis period avoidance rule of Article 72, item 2, of the old Bankruptcy Act.

Context: Evolution of Security over Future Claims and Avoidance

The use of future accounts receivable as security is a common and important financing tool. As noted in the provided PDF commentary, various methods have been employed in Japan:

- "Original Type" (本来型 - honrai gata): The assignment of claims is effective immediately upon the conclusion of the security agreement. If perfection (e.g., notice to account debtors with a certified date, or registration under Japan's Act on Special Provisions, etc. of the Civil Code Concerning the Perfection Requirements for the Assignment of Movables and Claims) is also completed at that time, this form of security is generally considered robust against later avoidance, assuming no other grounds for avoidance exist (like fraudulent intent from the outset). If perfection is delayed until after the assignor's financial crisis begins, the act of perfection itself might be challenged and avoided under specific rules (Article 164 of the current Bankruptcy Act, similar to Article 74 of the old Act).

- "Conditional Type" (停止条件型 - teishi jōken gata): This is the type at issue in the 2004 Supreme Court case, where the assignment "springs" into effect upon a crisis event.

- "Reservation Type" (予約型 - yoyaku gata): This involves an agreement to assign claims in the future, typically upon the occurrence of certain events, sometimes coupled with the perfection of the reservation right itself.

The "conditional" and "reservation" types were often developed by practitioners partly to address business concerns: immediate notification to all account debtors about an assignment of receivables could negatively impact the assignor's creditworthiness and business relationships. These structures attempted to provide security to the lender while delaying full public disclosure or direct debtor notification until absolutely necessary. However, as this Supreme Court decision illustrates, such structures, if they appear designed to give a creditor an advantage specifically triggered by the debtor's insolvency, face a high risk of being unwound in a subsequent bankruptcy.

The Supreme Court's decision in this case is seen as part of a broader judicial trend that looks critically at security arrangements that lack transparency or are structured to activate only upon the debtor's insolvency, especially if they appear to disadvantage the general pool of unsecured creditors. The development of a more robust and transparent statutory system for registering assignments of claims has also provided alternative means for securing such interests without resorting to complex conditional structures that might attract the trustee's scrutiny.

Implications of the Ruling

The Supreme Court's 2004 judgment has several important implications:

- Clarity on "Springing" Security Interests: It provides clear authority that merely structuring an assignment of claims so that its legal effectiveness is timed to coincide with the debtor's financial crisis (like suspension of payments) will not shield that assignment from the trustee's avoidance powers.

- Emphasis on Economic Substance Over Formal Timing: The decision underscores the willingness of Japanese courts in bankruptcy matters to look beyond the formal date of a contract to the substantive economic reality of when the detrimental transfer of value effectively occurs from the perspective of the general creditor body.

- Relevance to Current Bankruptcy Law: While this case was decided under the provisions of the old Bankruptcy Act (specifically Article 72, item 2, concerning crisis period avoidance), its reasoning is considered highly relevant for interpreting the preferential act avoidance provisions of the current Bankruptcy Act (particularly Article 162). The core principle—that acts which are, in substance, equivalent to granting security or making a payment during the crisis period are avoidable, regardless of pre-crisis contractual frameworks designed to trigger them—remains potent.

- Guidance for Structuring Secured Transactions: The ruling serves as a caution for lenders and borrowers when structuring security over future assets, particularly accounts receivable. Arrangements that appear to give a creditor a "last-minute grab" of assets triggered by the debtor's insolvency are likely to be vulnerable. More straightforward, upfront, and transparent methods of creating and perfecting security interests are generally favored.

The PDF commentary also notes that while this decision focused on the "conditional type" of assignment, its reasoning would likely extend to the "reservation type" as well. There is ongoing discussion about whether this logic would apply with equal force to other types of "springing" security, such as mortgages that might have similar conditions precedent tied to the debtor's financial status.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 2004 decision on conditional "springing" assignments of claims represents a significant step in preventing the circumvention of bankruptcy avoidance rules. By focusing on the substantive intent and practical effect of such arrangements—which is often to preferentially secure one creditor at the expense of the general creditor body at the very moment of the debtor's financial collapse—the Court reinforced the bankruptcy trustee's ability to ensure a more equitable distribution of the bankrupt's assets. This ruling highlights that Japanese bankruptcy law will scrutinize transactions that, despite being contractually framed before a financial crisis, are designed to activate and transfer value only when that crisis becomes manifest, treating them as if they occurred within the critical insolvency period.