Splitting Debts, Not Dodging Them: Japanese Supreme Court on Good Faith in Company Splits and Creditor Protection

Judgment Date: December 19, 2017

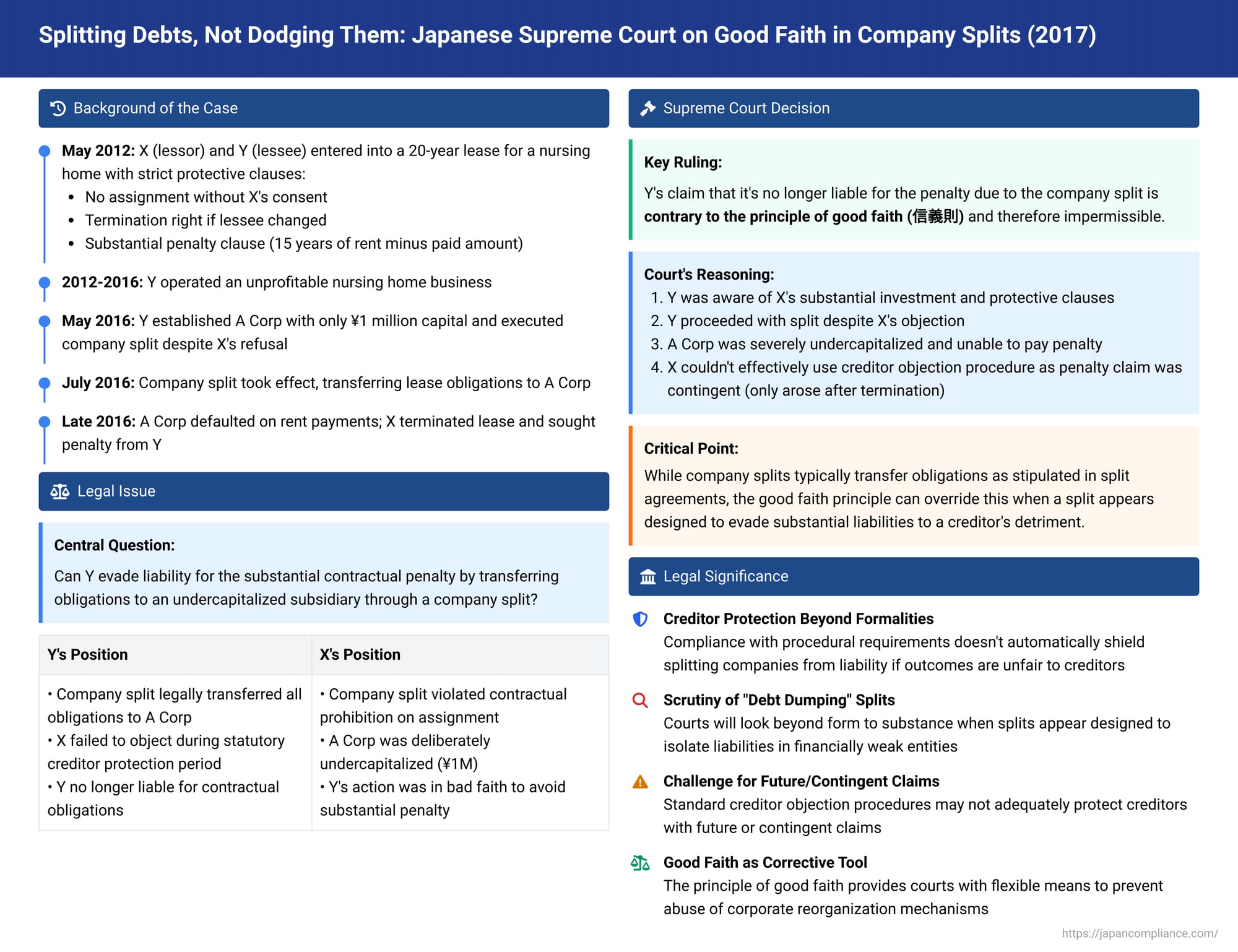

Company splits, or demergers (会社分割 - kaisha bunkatsu), are a common tool in Japan for corporate restructuring, allowing companies to transfer parts of their business to other entities. While the Companies Act provides a framework for how debts related to the transferred business are typically assumed by the successor company, a crucial question arises when such a split appears designed to shed significant liabilities, leaving creditors in a precarious position. A 2017 Supreme Court of Japan decision tackled such a scenario, invoking the fundamental principle of good faith (shingisoku - 信義則) to hold a splitting company liable for a substantial contractual penalty, even though the debt was nominally transferred to a thinly capitalized new subsidiary.

The Lease, the Unprofitable Venture, and the Strategic Split

The dispute originated from a long-term lease agreement entered into in May 2012 between X, the lessor, and Y, the lessee.

- The Agreement: X agreed to construct a specialized building for a nursing home ("the Building") based on Y's designs. Y, in turn, agreed to lease the Building from X for 20 years to operate a nursing home business ("the Business"). The monthly rent was substantial (¥4.99 million, with an initial 5-year period at ¥4.5 million).

- Key Protective Clauses for Lessor X: The lease agreement contained several clauses designed to protect X's significant investment (approximately ¥600 million to construct the Building) and ensure a stable return over the 20-year term:

- Y was prohibited from assigning its lease rights or subletting the Building without X's prior written consent.

- Given the specialized nature of the Building (making it difficult to repurpose) and X's investment horizon, Y was generally barred from terminating the lease mid-term.

- Termination Clause: X had the right to terminate the lease without prior notice if Y, among other things, substantially changed the contracting party of the lease.

- Penalty Clause: If X terminated the lease based on the aforementioned Termination Clause at any time before the first 15 years of the lease had passed, Y was obligated to pay X a penalty. This penalty was calculated as the total rent for 15 years minus the amount of rent already paid by Y up to the termination date.

Y commenced the nursing home business in the Building in November 2012, after X delivered it in October 2012. However, the Business proved unprofitable from its inception.

Facing these difficulties, around April 2016, Y conceived a plan to transfer the underperforming Business to a separate company via a company split. Y communicated this plan to X and sought X's approval, but X refused to consent.

Undeterred, Y proceeded:

- On May 17, 2016, A Corp was established as a new company, with Y providing its entire initial capital of just ¥1 million.

- On May 26, 2016, Y and A Corp executed an absorption-type company split agreement ("the Split Agreement"). This agreement stipulated that, effective July 1, 2016:

- All rights and obligations pertaining to the Business, explicitly including Y's contractual position and all rights and duties under the Lease Agreement, would be transferred from Y to A Corp.

- Along with the Business and its associated lease obligations, Y would also transfer ¥19 million in bank deposits to A Corp.

- Crucially, the Split Agreement included a provision stating that Y would no longer bear any responsibility for the rights and obligations related to the Business after the split effectively making A Corp solely liable.

- On May 27, 2016, Y made the legally required public notices (in the Official Gazette and a daily newspaper) regarding the impending company split. These notices informed creditors that they had a one-month period (from the day after the notice) to state any objections to the split, as per Article 789, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act.

- No creditors raised objections during this statutory period.

- The company split took effect on July 1, 2016.

Post-Split Default and Termination

Y paid the rent due under the Lease Agreement up to and including the July 2016 installment. However, after A Corp formally took over the Business and the lease obligations, it failed to pay the majority of the rent. By November 30, 2016, unpaid rent from A Corp amounted to ¥14.5 million.

In response to this situation, on December 9, 2016, X exercised its rights under the Lease Agreement's Termination Clause. X sent a notice of termination to both Y and A Corp, citing the company split as a "substantial change of the contracting party," which was a specified ground for termination by X. This termination, occurring within the first 15 years of the lease, triggered the substantial Penalty Clause.

X then sought a provisional attachment order against Y's assets (specifically, Y's receivables from third-party construction contracts and its bank deposits) to secure its claim for the penalty and unpaid rent, initially for ¥200 million. The Sendai District Court initially granted this, but later, upon Y's objection, cancelled the attachment order. X appealed to the Sendai High Court, reducing its secured claim to ¥185.5 million (representing only the penalty amount) and narrowing the attachment target. The High Court then partially reinstated the attachment order against Y's assets. Y appealed this reinstatement to the Supreme Court, arguing it was no longer liable for the penalty as the obligation had been transferred to A Corp through the company split.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Invoking the Principle of Good Faith

The Supreme Court, in its decision dated December 19, 2017, dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision that allowed X to pursue the attachment against Y for the penalty claim. The Supreme Court's reasoning was grounded in the principle of good faith.

- Acknowledgement of Company Split Mechanics: The Court began by acknowledging the standard legal effect of an absorption-type company split under the Companies Act (Articles 2(29), 757, 759(1), and 761(1)). Ordinarily, the rights and obligations related to the transferred business, including the Lease Agreement in this case, would indeed be succeeded to by the successor company (A Corp) as stipulated in the Split Agreement.

- Emphasis on the Specifics of the Lease Agreement: The Court then meticulously reviewed the terms of the Lease Agreement, highlighting:

- The mutual understanding that X had made a substantial investment to construct a specialized building, with the expectation of recovering this cost through stable rent payments from Y over a 20-year period.

- The clear intent behind X's inclusion of the prohibition on assignment, the Termination Clause (triggered by a substantial change of lessee), and the significant Penalty Clause. These provisions were specifically designed to protect X from the adverse consequences of a change in the lessee, particularly a change to a lessee with lesser financial standing or commitment.

- The Court found that Y had understood and accepted these terms and X's intentions when entering into the Lease Agreement.

- Analysis of Y's Actions and Their Impact on X: The Court then scrutinized Y's conduct:

- Y proceeded with the company split – an action that squarely fell under the Termination Clause as a "substantial change of contracting party" – without obtaining X's consent, despite X having previously refused to approve such a plan.

- A Corp, the entity to which these significant obligations were transferred, was established by Y with a mere ¥1 million in capital. The assets A Corp received from Y through the split (the Business and ¥19 million in cash) were "far below the amount of the penalty claim." It was evident that A Corp lacked the financial capacity to meet this substantial penalty.

- The Court painted a stark picture: If Y were allowed to completely shed its liability for the penalty simply by virtue of the split, Y would enjoy the economic benefit of offloading an underperforming business and its associated weighty penalty. Simultaneously, X would be left with a virtually unenforceable claim against A Corp, an entity clearly incapable of paying. This outcome, the Court stated, would be "grossly prejudicial" to X.

- Ineffectiveness of the Creditor Objection Procedure for X's Penalty Claim: A crucial element of Y's defense was that X had not objected during the statutory creditor protection procedure (Companies Act Article 789). However, the Supreme Court found this procedure to be ineffective for X concerning the specific penalty claim:

- The penalty claim under the Lease Agreement only arose and became a concrete debt when X exercised its right to terminate the lease. This termination was itself a consequence of the company split becoming effective.

- Therefore, during the one-month creditor objection period (which preceded the split's effective date and X's subsequent termination), X's claim for the penalty was still future and contingent upon events that had not yet occurred (i.e., the split taking effect, followed by X's act of termination).

- The Court concluded that X could not have been deemed to hold the (crystallized) penalty claim at the time of the objection period. Thus, X could not have validly objected to the split under Article 789, Paragraph 1, Item 2 with specific regard to this future penalty liability being transferred to A Corp.

- Application of the Principle of Good Faith (Shingisoku): Based on the entirety of these circumstances, the Supreme Court delivered its decisive conclusion:

Y's assertion that it is no longer liable for the penalty claim solely because the company split occurred is contrary to the principle of good faith and is therefore impermissible.

The Court held that X is entitled to demand performance of the penalty obligation from Y, even after the absorption-type company split transferred the primary lease obligations to A Corp.

Unpacking the Principle of Good Faith in Company Reorganizations

The principle of good faith (shingisoku) is a fundamental tenet of Japanese civil and commercial law, acting as a general clause that allows courts to ensure fairness and prevent abuse of rights or legal forms. In this case, it served as a vital corrective mechanism. The Supreme Court effectively found that Y's use of the company split mechanism, while formally compliant with some procedural aspects of the Companies Act, was, in its substance and effect concerning the penalty clause, an act of bad faith towards X.

The key factors contributing to this finding appear to be:

- The clear contractual intent to protect X from the risks of a change in lessee, which Y understood.

- The deliberate transfer of a significant potential liability to a newly created, manifestly undercapitalized subsidiary.

- The practical inability of X to use the statutory creditor objection procedure to protect itself against the transfer of this specific, large, and contingent penalty liability.

- The grossly unfair outcome that would result if Y were allowed to escape liability.

Analysis and Implications

This Supreme Court decision carries significant implications for corporate restructuring and creditor protection in Japan:

- Creditor Protection Beyond Formal Procedures: It demonstrates that compliance with the formal procedural requirements of a company split (like public notice for creditor objections) does not automatically shield the splitting company from all future liabilities, especially if the outcome is patently unfair to a creditor who had limited means to protect themselves during the formal process. The overarching principle of good faith can override the formal effects of the split.

- Scrutiny of "Debt Dumping" or "Liability Evasion" Splits: The ruling serves as a clear warning against structuring company splits in a way that appears primarily designed to isolate significant or troublesome liabilities in a financially weak successor entity, leaving creditors without effective recourse. Courts will look beyond the form to the substance and fairness of such transactions.

- Importance of Contractual Safeguards and Their Limitations: While X had robust contractual clauses (termination for change of lessee, substantial penalty), these were almost circumvented by Y's use of the company split combined with the argument that all liabilities transferred. The Supreme Court's intervention based on good faith shows that courts may step in when legal forms are used to undermine legitimate contractual expectations in a prejudicial way. However, legal commentators also note that the degree of "self-protection" a creditor builds into a contract might influence a court's willingness to invoke good faith. In this instance, X's contractual protections were significant, yet still nearly insufficient without the good faith argument.

- Challenges for Future and Contingent Claims in Creditor Objection Procedures: The decision highlights the inherent difficulty for creditors with future or contingent claims (like X's penalty claim, which depended on a future termination) to effectively utilize the standard creditor objection procedures associated with company splits. These procedures are primarily designed for existing, identifiable debts at the time of the split. This ruling might encourage further discussion on how to better protect such creditors.

- Fact-Specific Nature of Good Faith Rulings: It is important to remember that decisions based on the general principle of good faith are often highly fact-dependent. While this case provides strong precedent, its direct applicability to other scenarios will depend on the specific contractual terms, the nature of the liabilities, the conduct of the parties, and the overall fairness of the outcome.

This Supreme Court decision follows a line of cases where courts have sought to prevent the abusive use of corporate law mechanisms. Previously, a major concern was companies splitting off profitable divisions while leaving debts with an empty shell (addressed by allowing fraudulent conveyance claims and later by statutory amendments providing direct claims against successor companies). This case tackles the converse problem: hiving off an unprofitable division with its attendant liabilities to an undercapitalized entity. The invocation of good faith provides a flexible, albeit less predictable, tool to address such situations where formal statutory protections prove inadequate.

Conclusion

The December 19, 2017, Supreme Court decision underscores that while company splits are legitimate and valuable tools for corporate reorganization, they cannot be wielded in a manner that flagrantly violates the principle of good faith to the severe detriment of creditors. When a company attempts to use a split to offload a substantial, contractually agreed-upon penalty onto a newly formed, undercapitalized subsidiary, particularly when the creditor was practically unable to object to this specific liability transfer through statutory procedures, the splitting company may find itself still bound by that obligation. This ruling reinforces the judiciary's role in ensuring that corporate restructuring mechanisms serve their intended purposes without becoming instruments of unfair dealing.