Specificity in Attaching Bank Deposits: A 2011 Japanese Supreme Court Decision

Case Name: Appeal Against a Decision Dismissing an Execution Appeal Against a Decision Dismissing an Application for a Claim Attachment Order

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 23 (Kyo) No. 34

Date of Decision: September 20, 2011

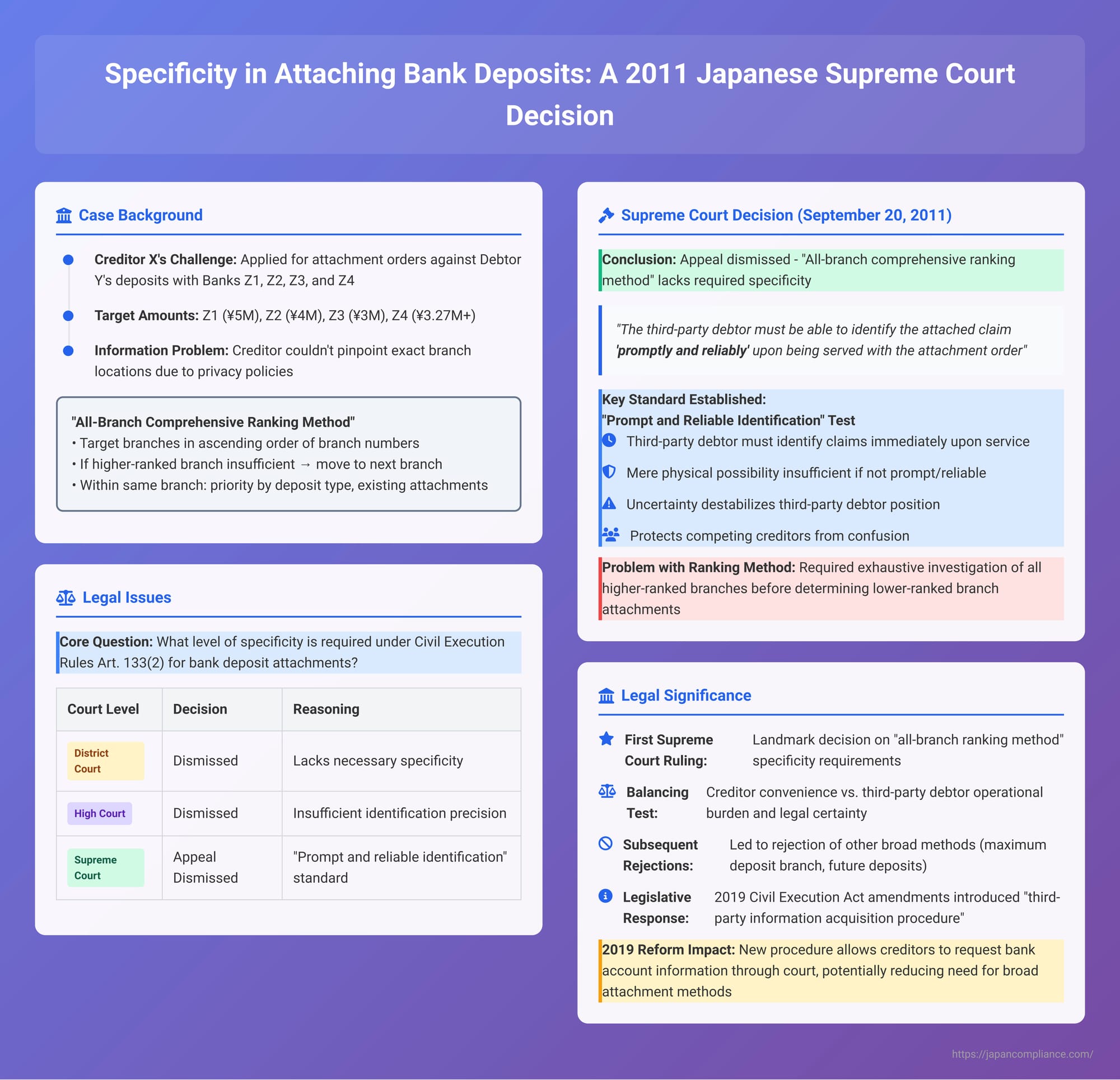

This article examines a pivotal Japanese Supreme Court decision from September 20, 2011, which addressed the level of specificity required when a creditor seeks to attach a debtor's bank deposit claims. The ruling has significant implications for how creditors must identify target assets in claim attachment orders, particularly when dealing with debtors holding accounts across multiple branches of large financial institutions.

The Creditor's Challenge and the "All-Branch Ranking" Approach

Creditor X, holding an enforceable monetary claim against Debtor Y, applied to the execution court for attachment orders against Debtor Y's deposit claims. These claims were held with several major financial institutions: Banks Z1, Z2, and Z3 (as third-party debtors, for claimed attachment amounts of JPY 5 million, JPY 4 million, and JPY 3 million, respectively) and Bank Z4 (for a savings claim, with a claimed attachment amount of over JPY 3.27 million).

In the application, Creditor X employed what is known as the "all-branch comprehensive ranking method" (zenten ikkatsu jun'izuke hōshiki) to identify the deposits to be attached. This method stipulated that if Debtor Y held deposits in multiple branches of the third-party banks (or Z4's savings processing center), the attachment should proceed by targeting branches in ascending order of their branch numbers (or, for Z4, by a number assigned by X). If the deposits at a higher-ranked branch were insufficient to cover the specified attachment amount, the deposits at the next-ranked branch would then be targeted, and so on. For deposits held within the same branch, a further order of priority was specified based on factors such as the existence of prior attachments or the type of deposit (e.g., term deposit, ordinary deposit).

This method was an attempt by the creditor to overcome the common difficulty of pinpointing the exact location and details of a debtor's bank accounts, a task often complicated by financial institutions' privacy policies.

Lower Courts' Stance: Lack of Specificity

Both the initial execution court and the High Court (on appeal) dismissed Creditor X's application. They found that the proposed method of identifying the claims to be attached lacked the necessary specificity required by Article 133, Paragraph 2 of the Rules of Civil Execution (Minji Shikkō Kisoku). This rule mandates that an application for a claim attachment order must clearly state the type, amount, and other particulars sufficient to identify the claim to be attached.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

Creditor X brought the case to the Supreme Court via a permission-to-appeal system. On September 20, 2011, the Supreme Court dismissed Creditor X's appeal, upholding the lower courts' decisions.

The Supreme Court laid down a general standard for the specificity of attached claims and then applied it to the "all-branch comprehensive ranking method":

- The "Prompt and Reliable Identification" Standard:

The Court stated that the specificity requirement of Civil Execution Rules Art. 133(2) means that the third-party debtor (e.g., the bank), upon being served with the attachment order, must be able to identify the attached claim "promptly and reliably" (sumiyaka ni, katsu, kakujitsu ni, sashiosaerareta saiken o shikibetsu suru koto ga dekiru). This identification must occur to a degree that is not inconsistent with the attachment taking legal effect at the precise moment of service.

The Court emphasized that merely being physically possible for the third-party debtor to identify the claim after expending a certain amount of time and following certain procedures is insufficient if it cannot be done with the requisite promptness and reliability. If an attachment order is issued based on a method of description that does not allow for such prompt and reliable identification, the precise scope of the attached claim remains uncertain between the service of the order and the completion of the identification process. This uncertainty could destabilize the position of the third-party debtor and other interested parties, such as competing attaching creditors. Therefore, such methods of describing the attached claim are impermissible. - Application to the "All-Branch Comprehensive Ranking Method":

The Supreme Court found that Creditor X's application, targeting all branches of large financial institutions with a cascading ranking system, did not meet this "prompt and reliable identification" standard.

The Court reasoned that for each third-party bank, the attachment of deposits in lower-ranked branches would only be determined after a full investigation of all deposits in higher-ranked branches. This investigation would involve confirming the existence of accounts, any prior attachments or provisional attachments, the type of deposits (term, ordinary, etc.), and the account balances at the exact moment the attachment order was served. Only after this exhaustive process for higher-ranked branches could the bank ascertain if, and to what extent, deposits in lower-ranked branches were affected by the attachment order.

This process, the Court concluded, would prevent the third-party banks from identifying the actually attached claims with the necessary promptness and reliability. Therefore, the application was deemed to lack the requisite specificity and was correctly dismissed as improper.

The judgment also noted a supplementary opinion by Justice Mutsuo Tahara, which further elaborated on the issues with the "all-branch comprehensive ranking method," considering its applicability beyond just financial institutions to other multi-branch businesses and highlighting the current limitations of bank IT systems (like Customer Information File or CIF systems) in immediately responding to such complex attachment requests. Justice Tahara's opinion also pointed to the potential for significant disruption to transactions and the instability it would cause for competing creditors if such broad attachment methods were permitted.

Analysis and Significance

This 2011 Supreme Court decision was a landmark ruling, being the first by the nation's highest court to directly address the permissibility of the "all-branch comprehensive ranking method" for attaching bank deposits.

- Establishing a Clear Standard: The "prompt and reliable identification" standard provides a general benchmark for assessing the specificity of claims in attachment orders. This standard prioritizes the ability of the third-party debtor (often a bank) to quickly and accurately understand the scope of the attachment upon service, which is critical because the attachment's legal effects (like the prohibition on payment to the debtor) arise immediately.

- Balancing Creditor Rights and Third-Party Burdens: The decision reflects a careful balancing act. While acknowledging the difficulties creditors face in obtaining detailed information about debtors' assets, the Supreme Court ultimately gave more weight to the operational burdens, risks (such as double payment or liability for non-payment), and legal uncertainties that overly broad attachment applications could impose on third-party debtors, particularly large financial institutions. Before this ruling, lower court decisions had been divided, with some permitting such broad methods by considering banks' advanced IT systems (like CIF) and suggesting legal mechanisms to protect banks from liability for errors made during the identification process. The Supreme Court, however, was not persuaded that existing systems could handle such requests with the required speed and certainty without causing undue disruption.

- Impact on Subsequent Case Law: The "prompt and reliable identification" standard has been applied by the Supreme Court in subsequent cases to reject other innovative but broad methods of specifying claims for attachment. For example:

- The "maximum deposit branch designation method" (targeting the branch with the highest aggregate deposit balance) was also found to lack specificity (Sup. Ct., Jan. 17, 2013).

- An attempt to attach future deposits made into an ordinary savings account up to one year after the service of the attachment order (the "future ordinary deposit inclusion method") was similarly rejected (Sup. Ct., Jul. 24, 2012).

These subsequent rulings indicate a consistent application of the standard established in the 2011 decision.

- The Role of Information Asymmetry and Legislative Solutions: The underlying problem that led creditors to attempt methods like the "all-branch ranking" is the difficulty in obtaining precise information about a debtor's assets. The Supreme Court's decision, while providing legal clarity, did not itself solve this practical problem for creditors.

However, a significant legislative development occurred with the 2019 amendments to the Civil Execution Act. These amendments introduced a new "third-party information acquisition procedure" (daisansha kara no jōhō shutoku tetsuzuki). This allows creditors, through the court, to request financial institutions and other relevant third parties to provide information about a debtor's assets, including bank account details (Civil Execution Act Art. 207(1)(i)). This reform directly addresses the information gap and, if effectively utilized, may reduce the need for creditors to resort to overly broad or indirect methods of specifying claims in attachment applications. The success of this new system will depend on its practical implementation and accessibility.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's September 20, 2011, decision established a crucial benchmark for the specificity required in applications to attach bank deposit claims in Japan. By prioritizing the "prompt and reliable identification" of attached assets by the third-party debtor, the Court disallowed the "all-branch comprehensive ranking method" for large financial institutions, thereby emphasizing the need to minimize operational disruption and legal uncertainty for these institutions. While this ruling posed challenges for creditors struggling with information asymmetry, subsequent legislative reforms aimed at improving creditors' access to information about debtors' assets may offer a more direct solution, potentially reducing reliance on the types of broad attachment applications addressed in this case.