Sovereign Immunity Redefined: Japanese Supreme Court Adopts Restrictive Approach

Date of Judgment: July 21, 2006

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

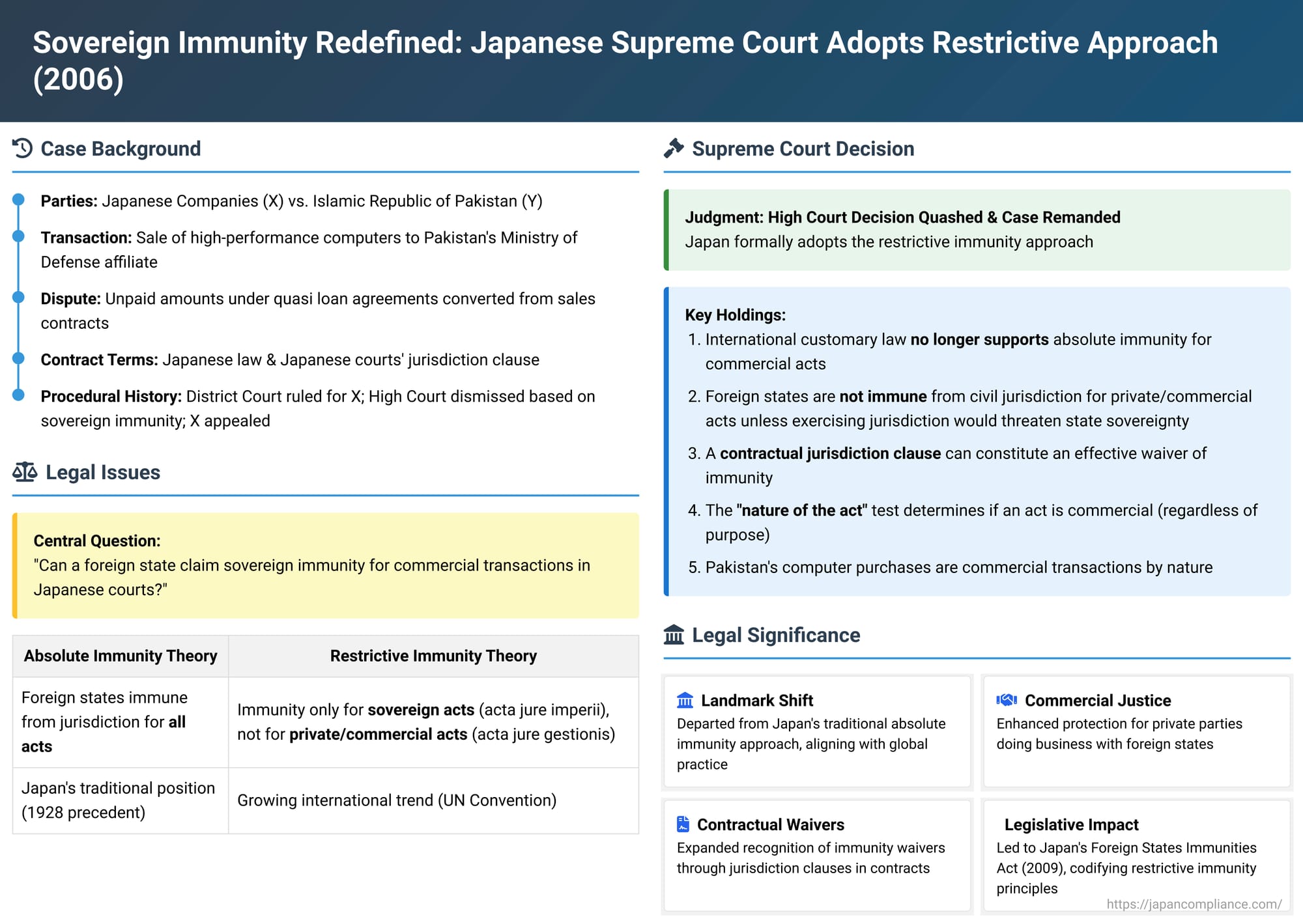

The principle of sovereign immunity, which traditionally shielded foreign states from the jurisdiction of domestic courts, has undergone significant evolution globally. Historically, the doctrine of "absolute immunity" prevailed, granting states broad protection from lawsuits. However, as states increasingly engaged in commercial activities, the theory of "restrictive immunity"—which distinguishes between a state's sovereign acts (acta jure imperii) and its private or commercial acts (acta jure gestionis), granting immunity only for the former—gained widespread acceptance. A landmark decision by the Japanese Supreme Court on July 21, 2006, marked a pivotal shift in Japanese jurisprudence, formally aligning Japan with the restrictive immunity doctrine even before specific legislation was enacted.

The Factual Background: A Commercial Dispute with a Foreign State

The case involved Japanese companies, X et al. (the plaintiffs), and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan (Y) (the defendant).

- X et al. alleged that they had entered into sales contracts with A Corp., described as an affiliate of Pakistan's Ministry of Defence and acting as Pakistan's agent. The contracts were for the sale of high-performance computers and other goods.

- After delivering the goods, X et al. claimed that further agreements were made, converting the outstanding sales price debts into quasi loans-for-consumption (準消費貸借契約 - jun shōhi taishaku keiyaku).

- Crucially, the original sales contracts reportedly included a clause stipulating that Japanese law would govern any disputes arising from the contracts and that such disputes would be adjudicated in Japanese courts.

- When payments were allegedly not made, X et al. filed a lawsuit in the Tokyo District Court against Pakistan, seeking payment under these quasi loan agreements.

The Tokyo District Court initially ruled in favor of X et al., as Pakistan did not appear. However, Pakistan appealed to the Tokyo High Court, asserting sovereign immunity and requesting the dismissal of the suit. The High Court sided with Pakistan, dismissing the lawsuit. It reasoned that foreign states are generally immune from Japan's civil jurisdiction, and a waiver of this immunity would require a formal treaty or a direct state-to-state declaration of intent to submit to jurisdiction, neither of which was found in this case. X et al. then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Journey: From Absolute to Restrictive Immunity in Japan

For a long time, Japanese case law, notably a 1928 decision by the Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation, the predecessor to the Supreme Court), had largely followed the principle of absolute immunity. This meant foreign states were generally immune from suit in Japanese courts unless they explicitly consented.

However, international law and state practice had been steadily moving towards restrictive immunity. The 2004 United Nations Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property (though not yet in force globally at the time of this judgment) also adopted a restrictive approach. Even before this 2006 ruling, there were signs of a potential shift in Japanese judicial thinking, such as the 2002 Yokota Air Base case, where the Supreme Court, while granting immunity to the United States, did so by reasoning that the specific acts in question (military aircraft operations) were sovereign in nature.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Supreme Court, in its July 21, 2006 judgment, quashed the High Court's decision and remanded the case, fundamentally altering Japan's legal landscape concerning sovereign immunity.

1. International Customary Law No Longer Supports Absolute Immunity for Commercial Acts:

The Court observed the widespread state practice and international developments, including the UN Convention. It concluded that:

- While international customary law continues to support the principle that foreign states are immune from the jurisdiction of a forum state for their sovereign acts (acta jure imperii).

- There is no longer an established international customary law granting foreign states immunity for their private law or operational/management acts (acta jure gestionis / 私法的ないし業務管理的な行為 - shihōteki naishi gyōmu kanriteki na kōi).

2. Rationale for Adopting Restrictive Immunity:

The Court reasoned that sovereign immunity stems from the mutual respect for the sovereignty and equality of independent states. However:

- Exercising civil jurisdiction over a foreign state's private law or operational/management acts typically does not infringe upon its sovereignty. Therefore, there is no rational basis for granting immunity for such acts.

- To grant immunity even in cases where a state's sovereignty is not threatened would lead to unfair outcomes, unilaterally denying judicial remedies to private parties who have engaged in commercial dealings with foreign states.

- New Standard Established: A foreign state is not immune from Japan's civil jurisdiction concerning its private law or operational/management acts, unless there are special circumstances where the exercise of Japan's jurisdiction would pose a threat to the foreign state's sovereignty.

3. Broader Interpretation of Waiver of Immunity:

The Court also expanded the understanding of how a state might waive its immunity:

- A foreign state is, of course, not immune if it has consented to Japan's jurisdiction through international agreements (like treaties) or if it has voluntarily submitted to jurisdiction in a specific case (e.g., by initiating a lawsuit in Japan).

- Crucially, the Court added: A foreign state is also, in principle, not immune from jurisdiction over disputes arising from a contract with a private party if that contract includes an explicit written provision whereby the state agrees to submit to Japan's civil jurisdiction for such disputes. In such instances, the Court noted, exercising jurisdiction would generally not threaten the foreign state's sovereignty, and for the state to later claim immunity would often lack fairness and violate the principle of good faith.

4. "Nature of the Act" Test Preferred:

In determining whether Pakistan's alleged actions constituted private/commercial acts or sovereign acts, the Supreme Court focused on the nature of the transactions. It stated that if Pakistan, through its agent, entered into contracts to purchase computers and then into quasi loan agreements, these actions "are, by their nature, commercial transactions that private individuals can also perform." Therefore, "regardless of their ultimate purpose" (e.g., even if the computers were for use by the Ministry of Defence), these acts would qualify as private law or operational/management acts. This indicates a preference for the "nature of the act" test over the "purpose of the act" test.

5. Overruling Precedent:

The Supreme Court explicitly stated that the 1928 Daishin-in decision endorsing absolute immunity should be modified to the extent that it conflicted with this new ruling.

Application to the Case:

The Court found that Pakistan's alleged acts of contracting for the sale and financing of computers, if proven, would constitute private law or operational/management acts. Consequently, Pakistan would not be immune unless special circumstances (threatening its sovereignty) were shown. Furthermore, if the alleged jurisdiction clause existed in the contracts and A Corp. was indeed Pakistan's agent, this could be seen as Pakistan having clearly expressed its intention to submit to Japanese jurisdiction for these disputes.

Since the High Court had dismissed the suit based on the old absolute immunity doctrine without fully examining these factual allegations, the Supreme Court remanded the case for these issues to be properly considered.

Significance and Aftermath: The Foreign States Immunities Act

This 2006 Supreme Court decision was a groundbreaking jurisprudential development in Japan, aligning its approach to sovereign immunity with prevailing international standards.

- It marked a clear judicial shift from absolute immunity to restrictive immunity.

- It broadened the concept of how a foreign state could waive its immunity, recognizing the validity of jurisdiction agreements in contracts with private parties.

Shortly after this ruling, Japan moved to codify the principles of restrictive immunity. It signed the UN Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and Their Property in January 2007 and enacted the Act on the Civil Jurisdiction of Foreign States, etc. (外国裁判権法 - Gaikoku Saibanken Hō) in April 2009, which came into effect in April 2010. This Act now governs sovereign immunity issues in Japan and largely reflects the principles laid out in the UN Convention and affirmed by the Supreme Court in this case. While the Act provides the current legal framework, the Supreme Court's reasoning in this 2006 decision, particularly its adoption of the "nature of the act" test for distinguishing commercial from sovereign activities, may continue to inform the interpretation of the Act's provisions.

Conclusion

The 2006 Supreme Court judgment concerning the Islamic Republic of Pakistan was a landmark decision that significantly modernized Japan's approach to sovereign immunity. By judicially adopting the principle of restrictive immunity and recognizing contractual waivers of immunity, the Court brought Japanese jurisprudence into closer alignment with contemporary international law and practice. This ruling underscored a move towards greater accountability for states when they engage in commercial activities, ensuring that private parties are not unfairly deprived of judicial remedies, while still respecting the legitimate sovereign functions of foreign states. It paved the way for the subsequent enactment of comprehensive legislation on foreign state immunity in Japan.