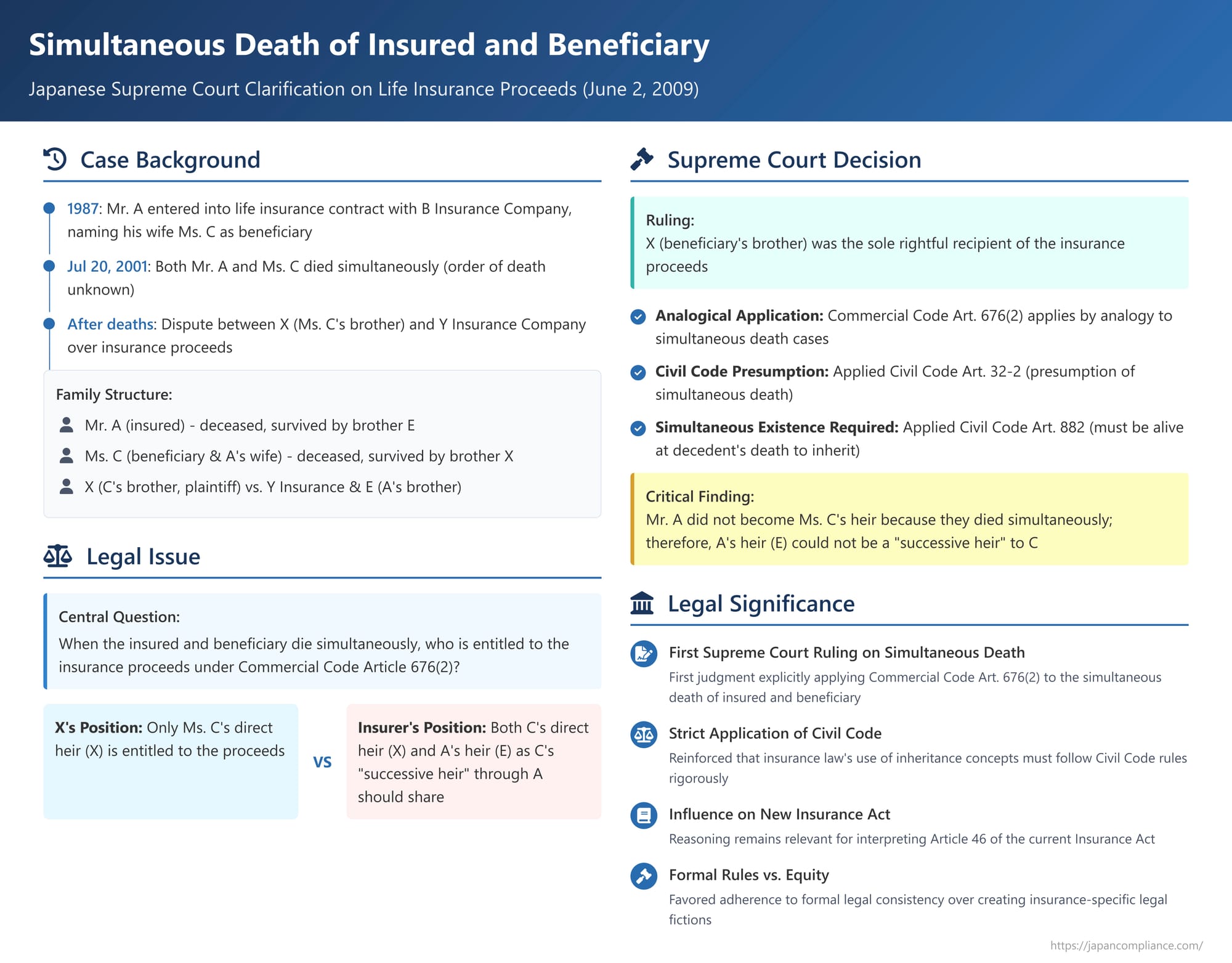

Simultaneous Death of Insured and Beneficiary: A Japanese Supreme Court Clarification on Life Insurance Proceeds

Date of Judgment: June 2, 2009

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Case No. 226 (ju) of 2009 (Claim for death benefits, etc.)

Life insurance policies are intended to provide a financial safety net, but tragic and unforeseen circumstances can lead to complex legal questions about who is entitled to the proceeds. One such scenario is the simultaneous death of the insured person and their designated beneficiary, or their death in circumstances where the order is unknown. A key decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on June 2, 2009, addressed this issue under the framework of the old Commercial Code, providing significant clarification on the interplay between insurance law and general principles of inheritance.

The Factual Background: A Tragic Coincidence

The case arose from a life insurance contract entered into by Mr. A on August 12, 1987, with B Insurance Company. Mr. A was the insured, and he designated his wife, Ms. C, as the beneficiary. Over time, the rights and obligations under this policy were transferred, first to D Insurance Company, and subsequently to Y Insurance Company, the defendant and appellant in the Supreme Court case.

On July 20, 2001, both Mr. A and Ms. C died. The critical aspect of their deaths was that the circumstances made it unclear whether one had survived the other, even briefly. This effectively treated their deaths as simultaneous for legal purposes.

The couple had no children. Both Mr. A's parents and Ms. C's parents had predeceased them. Mr. A's only sibling was his younger brother, E. Ms. C's only sibling was her older brother, X, who was the plaintiff and respondent in this case.

Following the deaths of A and C, X (Ms. C's brother) lodged a claim for the insurance proceeds with Y Insurance Company. X based his claim on being the rightful beneficiary under the provisions of Japan's former Commercial Code, specifically Article 676, paragraph 2 (a provision that corresponds to Article 46 of the current Insurance Act).

Y Insurance Company contested X's sole entitlement to the proceeds. The insurer argued that the beneficiaries should include not only Ms. C's direct heir (her brother, X) but also Ms. C's "successive heir". Their reasoning was that if Ms. C were deemed to have died first, Mr. A (her husband) would have been her statutory heir. Since Mr. A also died, his own statutory heir (his brother, E) would then step into Mr. A's shoes as a successive heir to Ms. C's rights concerning the insurance. Thus, the insurer contended that E should also share in the proceeds.

The lower courts, both the Kobe District Court (first instance) and the Osaka High Court (second instance), ruled largely in favor of X. They applied Article 676(2) of the old Commercial Code by analogy to the simultaneous death scenario and, relying on the legal presumption of simultaneous death, concluded that X was the sole statutory heir of Ms. C and therefore the rightful recipient of the insurance money. Y Insurance Company appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that in cases of simultaneous death, the designated beneficiary (Ms. C) should be treated as having died before the policyholder/insured (Mr. A) for the purposes of applying Article 676(2).

The Legal Quagmire: Old Commercial Code and Simultaneous Death

The core of the dispute lay in the interpretation and application of Article 676, paragraph 2, of the old Commercial Code. This article provided a default rule for determining the beneficiary when the person originally designated to receive the insurance amount died before the insured, and no new beneficiary was named. The challenge for the Supreme Court was to determine how this provision, designed for sequential deaths, should operate when the deaths were, legally speaking, simultaneous.

The Supreme Court's Decision and Reasoning

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Insurance Company's appeal, affirming the lower court's decision that X was the sole beneficiary. The Court's reasoning was methodical:

- Analogical Application to Simultaneous Death: The Court first established that the provisions of Article 676(2) of the old Commercial Code should indeed be applied by analogy in cases where the policyholder (who was also the insured, Mr. A) and the designated beneficiary (Ms. C) die simultaneously. This confirmed the approach taken by the lower courts.

- "Heirs of the Beneficiary" Defined: The Court then reiterated its established interpretation of the crucial phrase "heirs of the person who is to receive the insurance amount" as used in Article 676(2). Citing its own precedent from September 7, 1993 (Heisei 5), it stated that this phrase refers to the statutory heirs of the originally designated beneficiary, or their successive statutory heirs, who are actually living at the time of the insured's death.

- Civil Code Governs Heirship: The determination of who qualifies as a "statutory heir" in this context is to be made strictly according to the provisions of the Japanese Civil Code.

- The Impact of Simultaneous Death Presumption (Civil Code Article 32-2): Under Article 32-2 of the Civil Code, if two or more persons die and it is unclear which of them died first, they are presumed to have died simultaneously. Applying this to the case, Mr. A and Ms. C were presumed to have died at the same moment.

- No Inheritance Between Simultaneously Deceased Persons (Civil Code Article 882): The Court then invoked the principle of "simultaneous existence" for heirship, as stipulated in Article 882 of the Civil Code. This principle dictates that a person must be alive at the time of another person's death to inherit from them. Because Mr. A was presumed to have died at the same instant as Ms. C, he was not alive at the moment of her (presumed) death. Therefore, Mr. A did not become a statutory heir of Ms. C.

- Consequence for Successive Heirs: Since Mr. A did not become Ms. C's heir, his own heir (his brother, E) could not become a "successive heir" to Ms. C through Mr. A under the insurance provision. There was no inheritable right or status from Ms. C that could pass through Mr. A to E in this context.

- Outcome: The Court concluded that, applying Article 676(2) of the old Commercial Code in light of these Civil Code principles, the only person who qualified as the beneficiary was Ms. C's statutory heir who was alive and not simultaneously deceased with her – namely, her brother, X. The Supreme Court found no grounds to exclude the application of Civil Code Article 32-2 and treat the situation as if Ms. C had died before Mr. A.

Unpacking the Rationale: Legal Principles at Play

The Supreme Court's decision underscores a strict adherence to the formal rules of the Civil Code when interpreting insurance law provisions that rely on concepts of heirship. The insurer's argument essentially asked the Court to create a legal fiction for insurance purposes—to treat the deaths as sequential (beneficiary first) even though the Civil Code presumed them to be simultaneous. The Court declined to do this, prioritizing consistency with the general principles of inheritance law.

The judgment turned on the precise interaction between:

- Former Commercial Code Article 676(2): This insurance-specific rule aimed to find a recipient for the proceeds when the named beneficiary was unavailable due to prior death.

- Civil Code Article 32-2: This establishes a legal presumption of simultaneous death when the order of death is uncertain.

- Civil Code Article 882: This embodies the "principle of simultaneous existence," requiring an heir to be alive at the moment of the decedent's death to inherit.

By applying these Civil Code provisions rigorously, the Court determined that Mr. A could not have inherited from Ms. C because, under the presumption, he was not living at the moment of her death. This directly blocked the path for Mr. A's brother, E, to claim a share of the insurance proceeds as a successive heir of Ms. C via Mr. A.

Scholarly Debate and Alternative Views

This 2009 Supreme Court decision was the first to directly apply the old Commercial Code's beneficiary predecease rules, by analogy, to a simultaneous death scenario involving the policyholder/insured and the designated beneficiary. While providing clarity, it also touched upon ongoing academic discussions.

Support for the Judgment:

Many legal commentators support the Court's approach, emphasizing:

- Legal Certainty: A strict application of Civil Code rules for determining heirs provides a clear and predictable framework.

- Consistency with Inheritance Law: It aligns the treatment of "heirs" in insurance contexts with the general principles governing inheritance. The reasoning is that if insurance law borrows the concept of "heirs" from the Civil Code, it should generally adhere to the Civil Code's definitions and operational rules unless there's a compelling reason otherwise.

- Default Rule: Given that Article 676(2) was an optional provision (meaning parties could specify different outcomes in the insurance contract), the Court's interpretation provides a sound default rule for cases where no such specific agreement exists. This promotes stable insurance practices.

Critiques and Alternative Perspectives:

However, some scholars have raised concerns or proposed alternative interpretations:

- Perceived Inequity: A primary criticism is that this approach can lead to the insurance proceeds being "monopolized" by the designated beneficiary's family line (in this case, X), potentially excluding the policyholder/insured's family line (E), even if the policyholder (Mr. A) paid the premiums and might have wished for a broader distribution in such a tragic event.

- Policyholder's Intent: Opposing views often suggest that in simultaneous death cases, it might be more aligned with the policyholder's presumed rational intent to treat the situation as if the designated beneficiary died first. This would allow the policyholder/insured (as an heir of the beneficiary) or their family line to share in the proceeds.

- Flexibility of "Heir" Concept: Some argue that the concept of "heir" in insurance law need not be an exact, inflexible replica of its Civil Code counterpart, and that insurance law could adopt a more tailored interpretation to achieve results deemed more equitable or aligned with the specific purposes of insurance.

- Consistency with Prior Rulings: There were arguments that the decision might not sit entirely comfortably with the spirit of the Heisei 5.9.7 ruling, which, while establishing a chain of succession, was also seen by some as aiming to distribute benefits broadly when the policyholder's intent was unclear.

The commentary acknowledges a fundamental difficulty: regardless of which interpretive stance is taken (strict Civil Code application leading to the beneficiary's line, or a beneficiary-first fiction potentially including the insured's line), scenarios can arise where proceeds go to very distant relatives, an outcome perhaps never actively contemplated or desired by the original policyholder.

Relevance to the Current Insurance Act (Article 46)

The old Commercial Code provision (Article 676(2)) at the heart of this case has been superseded by Article 46 of the current Insurance Act of Japan. Article 46 generally states that if the designated beneficiary dies before the insured event, "all of their heirs become beneficiaries". This wording is seen as largely consistent with the principles of the Supreme Court's Heisei 5.9.7 decision.

The core logic of the 2009 Supreme Court decision—that in a simultaneous death scenario, the strict application of Civil Code heirship rules (particularly Articles 32-2 and 882) means no inheritance occurs between the simultaneously deceased parties—is widely considered to be applicable when interpreting the new Article 46 as well. Thus, even under the new Act, if an insured and beneficiary die simultaneously, the insured would likely not be considered an heir of the beneficiary for the purpose of determining who receives the insurance proceeds via the beneficiary's lineage. Some minor textual critiques of Article 46's phrasing ("before the insured event") exist in the context of truly simultaneous deaths, but the substantive reasoning from the 2009 case is expected to hold sway.

Significance of the 2009 Ruling

The Supreme Court's decision of June 2, 2009, carries notable significance:

- It was the first Supreme Court judgment to explicitly extend, by analogy, the old Commercial Code's rules for beneficiary predecease (Article 676(2)) to the specific situation of the simultaneous death of the policyholder/insured and the designated beneficiary.

- It provided crucial clarity on how fundamental Civil Code principles of inheritance, especially the presumption of simultaneous death and the requirement for an heir to be living at the decedent's death, interact with insurance beneficiary clauses under the former Commercial Code.

- While interpreting a now-superseded provision, its reasoning on the application of Civil Code heirship rules in simultaneous death situations is influential for understanding the operation of the current Insurance Act (Article 46).

Concluding Thoughts

In the face of a profoundly tragic event—the simultaneous deaths of an insured individual and their spouse, the designated beneficiary—the Supreme Court of Japan opted for a path of formal legal consistency. By strictly applying the Civil Code's rules on simultaneous death and heirship to the insurance context, the Court provided a clear, albeit for some, potentially counterintuitive, outcome. The decision favored the designated beneficiary's surviving family line, based on the legal premise that no inheritance could occur between those presumed to die at the same instant. This ruling highlights the ongoing dialogue in law between adherence to formal rules for predictability and the pursuit of outcomes that might align more closely with the unexpressed, presumed intentions of individuals in complex, unforeseen circumstances.