Silent Partnerships and Tax Treatment: Japan's Supreme Court on Income Classification and Reliance on Tax Circulars

Judgment Date: June 12, 2015

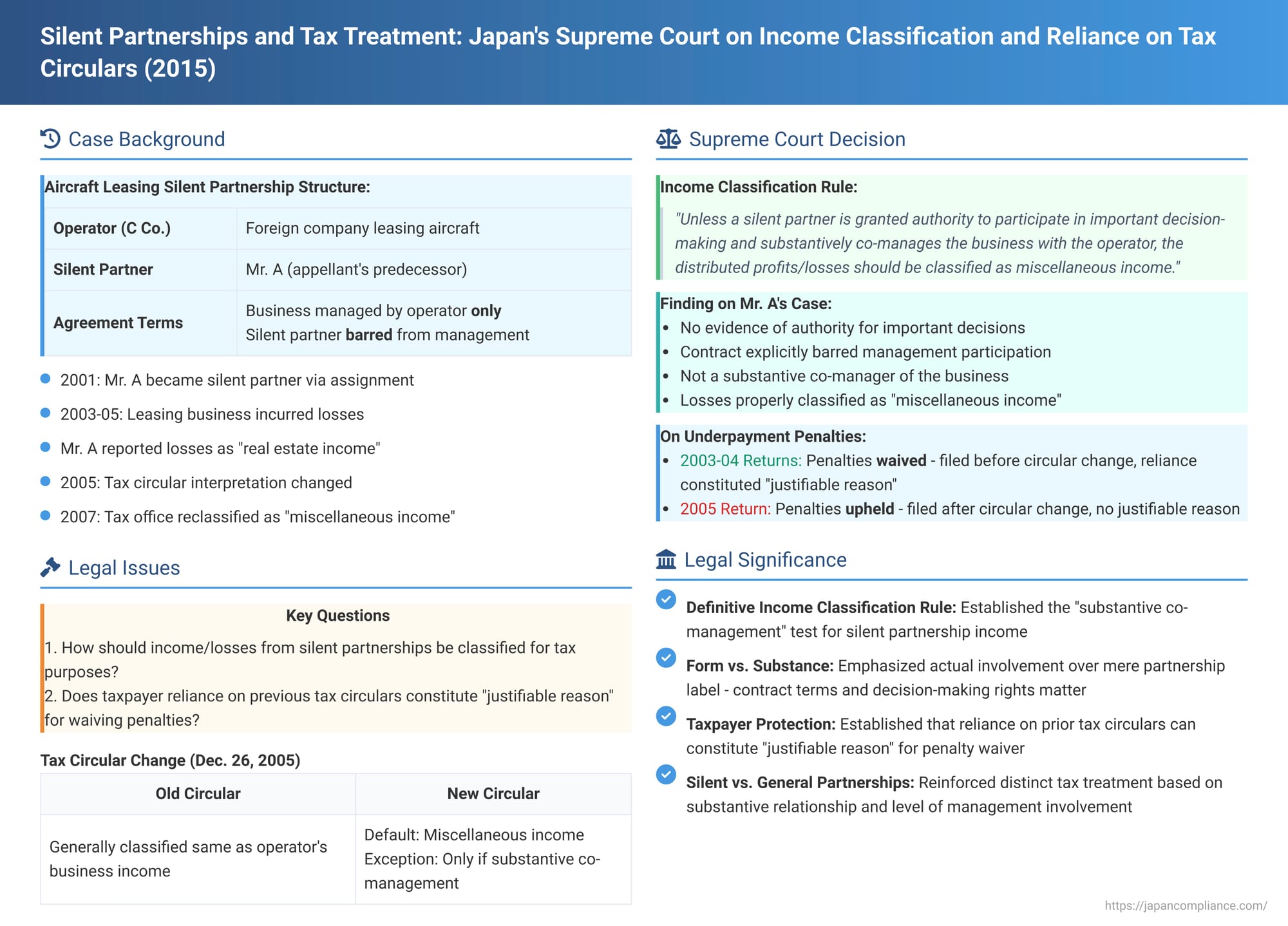

In a closely watched decision with significant implications for investors in silent partnerships (tokumei kumiai - 匿名組合), the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan clarified how income or losses distributed to individual silent partners should be classified for income tax purposes. The Court ruled that such distributions are generally to be treated as "miscellaneous income," unless the silent partner can demonstrate substantive involvement in the management and decision-making of the operator's business. The case also provided important guidance on when a taxpayer's reliance on previous administrative interpretations (tax circulars) can constitute a "justifiable reason" for waiving underpayment penalties following a change in that interpretation.

Background: An Aircraft Leasing Silent Partnership

The case involved the deceased Mr. A, whose successors in litigation were the appellants, X. Mr. A had invested as a silent partner in an aircraft leasing business.

The structure was as follows:

- On November 30, 2000, "B Co." entered into a silent partnership agreement with "C Co.," a foreign corporation, which acted as the "operator" (eigyōsha - 営業者) of the business. The purpose of the silent partnership was for C Co. to engage in leasing aircraft to foreign airline companies ("the subject leasing business").

- On March 1, 2001, Mr. A, by way of an assignment agreement with B Co. (and consented to by C Co.), acquired a portion of B Co.'s status as a silent partner in the subject leasing business, effective retroactively to November 30, 2000. Mr. A paid his contribution for this status on July 13, 2001.

Key Terms of the Silent Partnership Agreement:

The silent partnership agreement and the subsequent assignment agreement stipulated, among other things:

- Profit/Loss Distribution: Any profits or losses generated by C Co. from the subject leasing business during each accounting period (October 1 to September 30 annually) would be distributed to the silent partners (including Mr. A) according to their respective contribution ratios.

- Operator's Sole Discretion: The subject leasing business was to be conducted under the sole discretion and management of the operator, C Co.

- No Silent Partner Involvement: The silent partners were explicitly barred from participating in or influencing the conduct or management of the subject leasing business in any manner.

- Operator's Authority: C Co. was authorized to enter into any contracts and take any actions it deemed necessary or beneficial to achieve the objectives of the leasing business, on terms it considered appropriate.

Crucially, the contractual documents contained no provisions granting the silent partners, including Mr. A, any authority to participate in important decision-making concerning C Co.'s leasing business. Nor was there any evidence of a separate agreement granting Mr. A such powers.

The Tax Dispute: Classification of Losses

The subject leasing business incurred losses during the accounting periods ending September 30, 2003, 2004, and 2005. Mr. A's allocated share of these losses was reported on his Japanese income tax returns for the calendar years 2003, 2004, and 2005 as losses arising from "real estate income" (不動産所得 - fudōsan shotoku). He then offset these losses against his other sources of income, reducing his overall tax liability.

The tax office disagreed with this classification. Following a change in relevant administrative circulars in late 2005 (discussed below), the tax office, in February 2007, issued corrective assessments for Mr. A's 2003-2005 income tax. The tax office contended that the losses distributed from the silent partnership did not qualify as real estate income losses and, therefore, could not be offset against other income in the manner claimed by Mr. A (losses from "miscellaneous income," for instance, generally cannot be offset against other income categories). The tax office also imposed underpayment penalties.

Mr. A's successors, X, challenged these assessments.

Understanding Silent Partnerships (Tokumei Kumiai)

A "silent partnership" (tokumei kumiai) is a specific type of contractual business arrangement defined under the Japanese Commercial Code. Its key characteristics are:

- A silent partner (or anonymous partner) contributes capital to an operator (eigyōsha) for the operator's business.

- In return, the silent partner receives a share of the profits generated by that business.

- The capital contributed by the silent partner becomes the property of the operator.

- The silent partner generally has no right to participate in the execution of the business or to represent the operator. They also typically have no direct rights or obligations towards third parties concerning the operator's business activities.

- The silent partner's rights are usually limited, such as the right to inspect the operator's financial statements and business/property status under prescribed conditions.

This structure differs significantly from a general partnership (nin'i kumiai - 任意組合), where partners typically co-own partnership assets and are jointly involved in the business operations, with profits and losses directly attributable to them according to the underlying nature of the partnership's business.

The Lower Courts' Rulings

Both the first instance court and the appellate court had ruled against X, upholding the tax office's corrective assessments. They reasoned that a silent partner, under the Commercial Code, is essentially an investor, and the distributed profits (or losses) are primarily consideration for this investment. Therefore, they concluded that the losses did not qualify as real estate income losses. These courts also found no "justifiable reason" to waive the underpayment penalties, asserting that the 2005 change in tax circulars did not represent a fundamental shift in administrative interpretation that Mr. A could have permissibly relied upon for the earlier tax years.

X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: A Two-Pronged Analysis

The Supreme Court addressed two main issues: the correct income classification of the distributed losses and the applicability of underpayment penalties.

1. Income Classification for Silent Partner Distributions

The Supreme Court provided a clear framework for determining the income tax classification of profits or losses distributed from a silent partnership to an individual silent partner:

(a) The Default Position: Investor Status and "Dividend-Like" Returns

The Court began by analyzing the legal nature of a silent partner under the Commercial Code (both before and after its 2005 revision). It reiterated that the silent partner's role is primarily that of an investor who contributes capital to the operator's business and, in return, receives a share of the profits from that business. The contributed capital legally belongs to the operator, and the silent partner typically has no say in managing the business.

"Thus," the Court stated, "assuming the legal relationships stipulated by these Commercial Code provisions, it can be said that the silent partner merely holds the status of an investor in the business conducted by the operator. Therefore, the distribution of profits received by a silent partner from the operator based on a silent partnership agreement is fundamentally to be understood as having the nature of a type of dividend on the investment in the operator's business."

(b) The Exception: Substantive Co-Management

However, the Court acknowledged that the terms of a silent partnership agreement could be modified by the contracting parties to a certain extent. It carved out an exception:

"If, in the said agreement, the silent partner is granted authority, such as participation in important decision-making concerning the business conducted by the operator, and if it is recognized that the silent partner, through the exercise of such authority, substantively holds the status of one who co-manages the business jointly with the operator, then the distribution of profits received by such a silent partner from the operator based on the said agreement should be considered as having the nature of a distribution of profits generated by a joint business between the operator and the silent partner."

(c) The Resulting Income Classification Rule

Based on this distinction, the Supreme Court laid down the rule for income classification:

- If Substantively Co-Managing: In cases where the silent partner is found to be substantively co-managing the business with the operator, the income (or loss) distributed to the silent partner should be classified according to the nature of the operator's underlying business. For example, if the operator's business generates real estate income, the silent partner's share would also be real estate income.

- If Merely an Investor (Default Rule): In all other cases (i.e., where the silent partner does not have substantive co-management status), the income (or loss) distributed to the silent partner should be classified based on the nature of that income for the silent partner themselves. Given its "dividend-like" nature as a return on investment, such income is generally to be classified as "miscellaneous income" (zatsu shotoku) under Article 35, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act. An exception to this would be if the silent partner's investment itself is made as part of their own separate, ongoing business activities, in which case it could be classified as their business income.

The Supreme Court noted that a new Income Tax Basic Circular issued in 2005 (discussed below) reflected this same interpretative approach.

(d) Application to Mr. A's Case

Applying this framework to the facts, the Supreme Court found:

The silent partnership agreement between C Co. (the operator) and Mr. A (via B Co.) did not grant Mr. A any authority to participate in important decision-making regarding the aircraft leasing business. There was no evidence that Mr. A substantively co-managed the business with C Co. Furthermore, there was no indication that Mr. A's investment in this silent partnership was made as part of his own separate business operations.

Therefore, the Court concluded that the losses distributed to Mr. A from the silent partnership should be classified as miscellaneous income, not real estate income. As losses from miscellaneous income generally cannot be offset against other categories of income under Japanese tax law, the tax office's corrective assessments (which denied such offsetting) were deemed lawful.

2. Underpayment Penalties and "Justifiable Reason"

The Supreme Court then turned to the issue of the underpayment penalties. Article 65, Paragraph 4 of the Act on General Rules for National Taxes allows for such penalties to be waived if the taxpayer had a "justifiable reason" (seitō na riyū - 正当な理由) for the under-declaration. The Court reiterated its standard (citing previous decisions) that a "justifiable reason" exists when there are "objective circumstances genuinely not attributable to the taxpayer's fault, and imposing the underpayment penalty would, in light of the purpose of such penalties, be unjust or unduly harsh."

The Court then analyzed the change in the Income Tax Basic Circulars concerning the income classification of silent partnership distributions:

- The Old Circular (in effect before December 26, 2005): This circular generally treated distributions to silent partners (unless they were akin to loan interest) as having the same income character as the operator's underlying business. This interpretation was based on an understanding that silent partners were, in substance, co-managing the business, without explicitly requiring an examination of their decision-making powers in each specific contract.

- The New Circular (effective from December 26, 2005): This new circular adopted the approach later affirmed by the Supreme Court in this very case – distributions are principally miscellaneous income unless the silent partner has substantive co-management authority, in which case the income character follows the operator's business.

The Supreme Court found that this 2005 amendment to the circulars constituted a change in the tax authority's publicly expressed interpretation of the law. The old and new circulars differed in their default treatment and would lead to different outcomes in cases like Mr. A's, where there was no co-management.

Given this change:

- For tax returns filed before the New Circular was issued (i.e., Mr. A's returns for 2003 and 2004), a taxpayer who followed the Old Circular and classified their silent partnership distributions according to the operator's business nature (assuming it wasn't like interest) was relying on the then-existing public stance of the tax authority. Such reliance could not be dismissed as a mere subjective error of legal interpretation by the taxpayer.

- Under the Old Circular, the losses from the aircraft leasing business (which is a form of real estate activity) distributed to Mr. A would have been classified as real estate income losses.

- Therefore, for Mr. A's 2003 and 2004 tax returns, which were filed in accordance with the Old Circular before the public interpretation changed, there were objective circumstances genuinely not attributable to Mr. A's fault. Imposing underpayment penalties for these years would be unjust. Thus, a "justifiable reason" existed to waive the penalties for 2003 and 2004.

- However, for the 2005 tax return (filed in March 2006, after the New Circular had been issued), such "justifiable reason" did not exist, as the taxpayer could no longer claim reliance on the old interpretation. The penalty for 2005 was therefore upheld.

Judgment of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court ruled as follows:

- The parts of the lower court's judgment concerning the cancellation of the corrective tax assessments (i.e., the reclassification of losses) were upheld – the assessments were lawful. X's appeal on this point was dismissed.

- However, the parts of the lower court's judgment upholding the underpayment penalties for the 2003 and 2004 tax years were reversed. The Supreme Court cancelled these specific penalties, finding a "justifiable reason" for their waiver.

- The underpayment penalty for the 2005 tax year was upheld.

The litigation costs were apportioned accordingly.

Significance and Implications

This Supreme Court decision is a landmark for several reasons:

- Definitive Income Classification for Silent Partners: It provides the authoritative rule for classifying income/loss distributions to individual silent partners in Japan: by default, it is "miscellaneous income" unless the silent partner can prove substantive co-management of the operator's business, in which case it follows the character of the operator's business income.

- Emphasis on Contractual Reality and Actual Involvement: The ruling underscores that the specific terms of the silent partnership agreement and the actual degree of the silent partner's participation in significant business decisions are critical factors. Merely being a "partner" is not enough to automatically adopt the underlying business's income character.

- Guidance on "Justifiable Reason" and Reliance on Circulars: The decision offers important guidance on what constitutes a "justifiable reason" for waiving tax penalties. It acknowledges that a significant and official change in the tax authorities' administrative interpretation (as expressed in Basic Circulars) can form the basis for such a reason, protecting taxpayers who relied in good faith on the previous interpretation.

- Distinction from General Partnerships Affirmed: The ruling implicitly strengthens the distinction between the tax treatment of silent partnerships and general partnerships (nin'i kumiai). In general partnerships, a more direct "pass-through" of the income character from the partnership's business to the partners is typical, reflecting the partners' direct ownership and management roles. This case clarifies that silent partnerships are treated differently due to the silent partner's typically passive, investor-like role.

This judgment provides much-needed clarity for investors and operators involved in silent partnerships in Japan, highlighting the need for careful consideration of both the contractual terms and the actual operational involvement of silent partners when determining the tax implications of profit or loss distributions. It also offers a degree of protection to taxpayers when navigating changes in official tax interpretations.