Signs of the Times: Japanese Supreme Court Protects Tenant's Signage from New Owner

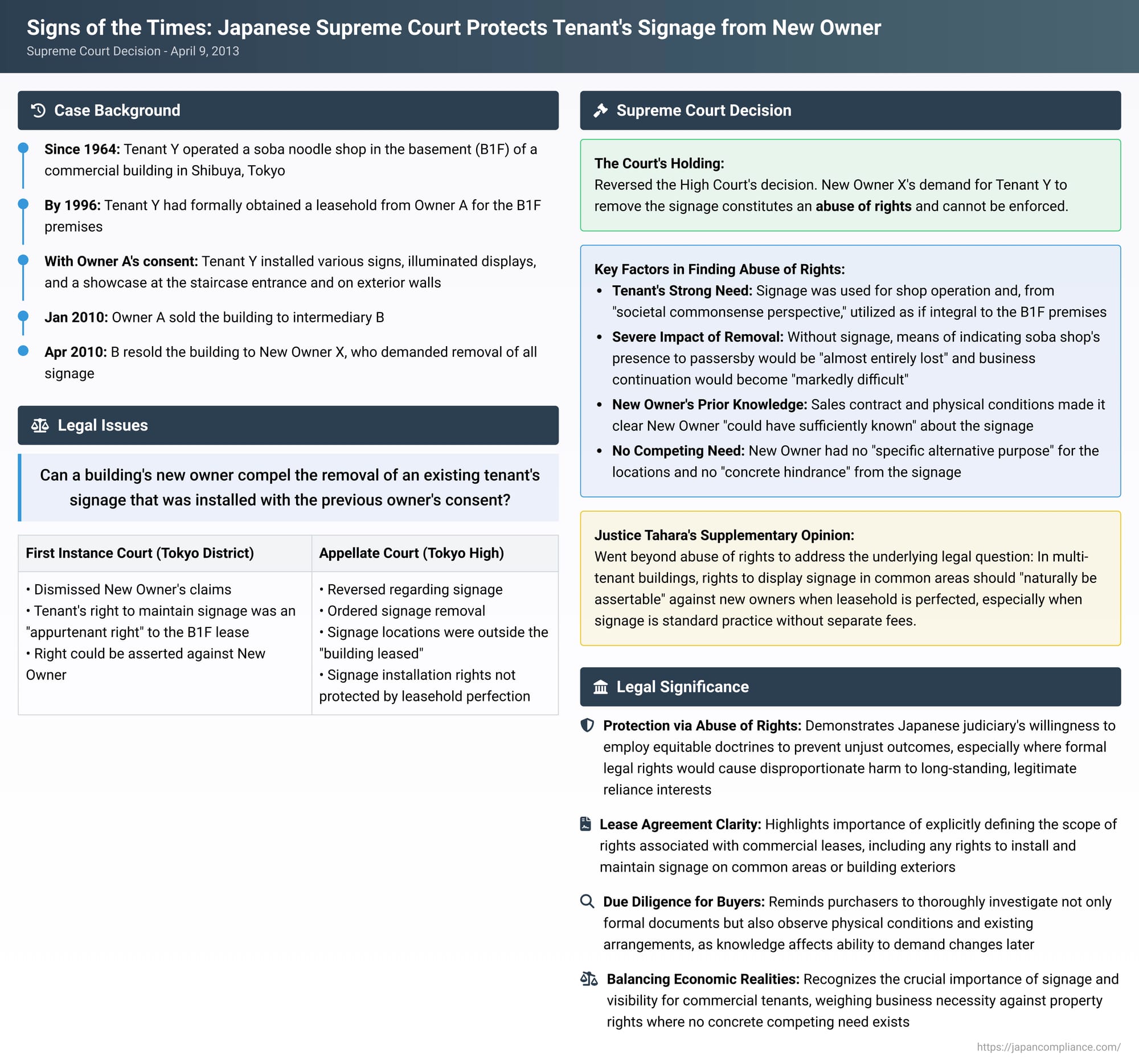

When a commercial building changes hands, what happens to the existing tenants' business signs, especially those affixed to parts of the building not explicitly included in their leased premises? Can a new owner compel their removal, even if the signs are crucial for the tenant's business and were installed with the previous owner's blessing? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed such a scenario in a notable judgment on April 9, 2013 (Heisei 25), in the Building Eviction, etc. Claim Case (Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Heisei 24 (Ju) No. 2280). The Court ultimately protected the tenant's right to maintain its signage, not by directly extending the tenant's leasehold rights to cover the external signage, but by deeming the new owner's demand for removal an "abuse of rights."

The Soba Shop and Its Signs: Factual Background

The appellant, Tenant Y, operated a soba noodle shop in the basement (B1F) of a building situated in a bustling commercial district of Shibuya, Tokyo. Tenant Y had been running the shop since around 1964 and had formally obtained a leasehold for the B1F premises from the then-owner, A, by September 1996 at the latest.

Crucially for the business's visibility, Tenant Y, with Owner A's consent, had installed various signs, illuminated displays, and a showcase (collectively, "the Signage") at the entrance to the staircase leading to the basement shop, as well as on the first-floor exterior walls and floor surface of the building. These items, while affixed, were removable.

In January 2010, Owner A sold the entire building to an intermediary, B. Shortly thereafter, in April 2010, B resold the building to the plaintiff-appellee, New Owner X. The sales agreement between B and New Owner X explicitly mentioned that the building was subject to existing leasehold burdens and also noted the presence of signage on the property.

Despite this, New Owner X asserted that Tenant Y's occupation of the B1F was merely based on a "loan for use" (shiyōshakuken)—a weaker right than a leasehold—and therefore could not be asserted against X as the new owner. Consequently, X demanded that Y vacate the B1F premises and, pertinent to this appeal, remove all the Signage. (The claim regarding vacating the B1F was eventually rejected by lower courts and was not the focus of the Supreme Court appeal regarding the signage.)

The Legal Journey: Lower Courts' Diverging Views

The dispute over the Signage took different turns in the lower courts:

- First Instance (Tokyo District Court): This court ruled entirely in favor of Tenant Y, dismissing all of New Owner X's claims. It found that Y's possession was based on a valid leasehold (chinshakuken) that had been duly perfected against third parties under Article 31 of Japan's Act on Land and Building Leases (Shakuchi Shakka Hō). Regarding the Signage, the court held that Y's right to maintain it could be asserted against New Owner X as an "appurtenant right" (jūtaru kenri) intrinsically linked to the B1F lease.

- Appellate Court (Tokyo High Court): The High Court upheld the dismissal of X's demand for Y to vacate the B1F. However, it reversed the first instance decision concerning the Signage, ordering Tenant Y to remove it. The High Court reasoned:

- The protective effect of Tenant Y's perfected leasehold under Article 31 extended only to the "building" leased, which it defined as the demarcated B1F unit itself and any parts structurally integral to it and used exclusively by the tenant. The locations where the Signage was installed (e.g., 1st-floor exterior walls) did not fall within this definition.

- Tenant Y's right to install the Signage was not primarily related to the "possession" of the leased premises but rather to the "business conducted through its use." Therefore, the perfection of the leasehold for the premises did not extend to this distinct right of signage installation.

- The High Court also concluded that New Owner X's demand for the Signage's removal did not constitute an abuse of rights.

Tenant Y appealed the High Court's order for the removal of the Signage to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Signage Stays (April 9, 2013)

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision regarding the removal of the Signage. It found that New Owner X's demand for Tenant Y to remove the Signage constituted an abuse of rights (kenri no ran'yō). The Court then reinstated the first instance judgment, which had dismissed X's claim for signage removal.

Reasoning: The Doctrine of Abuse of Rights to the Rescue

The Supreme Court's majority opinion hinged on the application of the abuse of rights doctrine. It meticulously weighed the circumstances of both parties:

- Tenant Y's Strong Need for the Signage:

- The Signage was demonstrably used for the operation of Tenant Y's soba shop in the B1F and, from a societal commonsense perspective (shakai tsūnenjō), had been utilized as if it were an integral part of the B1F premises.

- The Court emphasized the severe impact that removal would have: "If Tenant Y were compelled to remove the Signage, the means of indicating to passersby in the surrounding bustling commercial area that the soba shop was operating in the B1F would be almost entirely lost, and it is clear that the continuation of its business would become markedly difficult". Thus, Tenant Y had a "strong necessity" to use the Signage.

- New Owner X's Awareness and Lack of Detriment:

- The sales contract through which X acquired the building, along with the physical location and nature of the Signage, made it clear that X "could have sufficiently known" that the Signage was installed with the consent of the original building owner.

- Crucially, the Court found no evidence that New Owner X had any "specific alternative purpose" for the locations where the Signage was installed. Nor was there any indication that the continued presence of the Signage caused any "concrete hindrance" to X's ownership of the building.

- Balancing of Interests:

- Considering these circumstances—Tenant Y's significant reliance on the Signage for business survival versus New Owner X's apparent lack of specific need for the space occupied by the signs and X's prior awareness—the Court concluded that X's demand for removal was an abuse of X's property rights.

This application of the abuse of rights doctrine allowed the Court to achieve what it considered a fair and equitable outcome without directly resolving the more complex underlying legal question about the inherent scope of leasehold perfection concerning ancillary rights like signage.

Beyond Abuse of Rights: The Underlying Legal Question (The "Supplementary Opinion" and Commentary)

While the main opinion provided relief to Tenant Y through the abuse of rights doctrine, a supplementary opinion by Justice Mutsuo Tahara, and subsequent legal commentary, delved into the more fundamental question of whether Tenant Y's right to the Signage should have been directly protected as part of the perfected leasehold.

Justice Tahara's Supplementary Opinion:

Justice Tahara, while concurring with the majority's conclusion, expressed strong reservations about the High Court's narrow interpretation of Article 31 of the Act on Land and Building Leases. He argued:

- In multi-tenant buildings, it's common for features like tenant directory boards in lobbies, signage on common corridor walls, or external signboards listing tenants to be considered part of the lease agreement, even if not explicitly detailed in the written contract. This can occur when tenants can use such signage without separate fees or under general building rules.

- Therefore, if a tenant's leasehold right for their unit is perfected against a third-party acquirer of the building (as Y's was), the right to display signage under such terms should "naturally be assertable" (tōzen ni taikō suru koto ga dekiru) against the new owner. The mere fact that the signs are not within the tenant's independently possessed unit should not negate the application of Article 31's protection.

- He distinguished this from situations where a tenant's signage is based on a clearly separate agreement or is unique and different from what other tenants are permitted, in which case it might fall outside the scope of the lease agreement and thus outside Article 31 protection.

Justice Tahara also criticized the High Court for granting a provisional execution order for the signage removal given the circumstances.

Scholarly Debate and "Appurtenant Rights":

The case has prompted legal scholars to further analyze how rights ancillary to a lease, like signage, should be treated when a building is sold.

- The "Appurtenant Right" Argument: The first instance court's approach—viewing the signage right as an "appurtenant right" to the main leasehold—resonates with some scholarly views. This is particularly relevant because, unlike land leases which have established perfection methods (like registration), rights to affix movable signs typically do not have a distinct, independent perfection mechanism prescribed by law.

- Comparison to Integral Land Use Cases: Legal commentary often draws parallels to cases involving leases of multiple land parcels where only one parcel's lease is perfected (e.g., registered). Precedents have generally held that perfection for one land lease does not extend to an unperfected lease for an adjacent parcel, even if both are used integrally. The High Court's logic seemed to align with this restrictive view. However, many academics have criticized this precedent, arguing that if the integral use is externally apparent and it's practically difficult for the tenant to independently perfect the secondary right (e.g., for a garden or parking lot essential to the use of a building on the primary plot), perfection of the primary lease should extend to the ancillary one. This argument is seen as applying with even greater force to signage rights, given the lack of a clear independent perfection method.

- Legal Theories for Extending Protection to Signage Rights:

- Comprehensive Succession of Lease Terms: One theory posits that when a leasehold is perfected, the new owner comprehensively inherits the rights and obligations of the original lease agreement (based on a Supreme Court precedent, Showa 38.9.26). If the right to install signage is considered part of that original lease agreement (expressly or implicitly), the new owner would be bound to tolerate it. A later Tokyo District Court case (Reiwa 1.11.8) adopted this reasoning in a similar signage dispute.

- "Economic Integrality" and Accessory Rights: Another view suggests that even if the signage right stems from a technically separate agreement, if there is a strong "economic integrality" between the main building lease and the signage right, the perfection of the former could extend to the latter, viewing the signage right as an "appurtenant right" or "accessory" that follows the "principal" lease (potentially invoking Article 87, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code concerning accessories).

- Recognizability by Third Parties: Some theories add a condition that the third party (the new owner) must have been able to recognize the existence of the signage right from the building's state or usage situation for the tenant to assert it. This echoes the requirement in the land-lease context that the integral use be "externally apparent".

- The precise scope of how far a leasehold's perfection can extend to such ancillary rights, and the necessity of the new owner's ability to recognize the situation, remain active areas of academic discussion in Japan.

The Supreme Court's decision to use the abuse of rights doctrine in this instance provided a practical solution for Tenant Y but left these intricate questions about the direct effect of lease perfection on external signage rights largely for future cases or legislative clarification.

Key Takeaways and Practical Implications

This Supreme Court judgment offers several important insights:

- Protection via Abuse of Rights: It demonstrates the Japanese judiciary's continued willingness to employ the equitable doctrine of abuse of rights to prevent unjust outcomes in property disputes, particularly where a party with formal legal rights seeks to enforce them in a manner that causes disproportionate harm to another party with a long-standing, legitimate reliance.

- Importance of Lease Clarity: For both tenants and landlords, the case underscores the practical importance of clearly defining the scope of rights associated with a commercial lease, including any rights to install and maintain signage on common areas or the building exterior. Explicitly including such terms within the main lease agreement could strengthen a tenant's position.

- Due Diligence for Buyers: Prospective purchasers of commercial properties are reminded of the need for thorough due diligence. This includes not only reviewing formal lease documents but also observing the physical state of the property, noting existing signage, and inquiring about any agreements or consents related to them, as knowledge of such arrangements can impact their ability to later demand changes. The sales contract in this case actually noted the signage, which played a role in the Court's assessment of the new owner's awareness.

- Balancing of Interests: The Supreme Court's reasoning in the abuse of rights analysis—focusing on the tenant's necessity, the owner's lack of specific competing need or concrete detriment, and the owner's prior awareness—provides a framework that may be applied in similar future disputes involving ancillary rights critical to a tenant's business operations.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 2013 decision in the Shibuya soba shop signage case is significant for its pragmatic protection of a long-standing tenant's ability to maintain crucial business visibility against the demands of a new building owner. By finding an abuse of rights, the Court affirmed the importance of considering the practical realities and equities of the situation, particularly the severe hardship the tenant would have faced if the signs were removed, weighed against the new owner's lack of specific need for the space and prior awareness of the arrangement.

While the ruling was a victory for the tenant, the Court's reliance on the abuse of rights doctrine, rather than a definitive pronouncement on whether perfected leasehold rights inherently extend to such external signage, leaves some underlying legal questions open. Justice Tahara's supplementary opinion and ongoing academic discourse suggest a potential path towards recognizing more direct protection for such ancillary rights when they are integral to the lease's purpose and known to new owners. For now, the case stands as a key example of how Japanese law can balance formal property rights with the substantive needs of ongoing commercial operations.