Shunto vs. Japan’s Minimum Wage System: Navigating Dual Wage-Setting Mechanisms

TL;DR

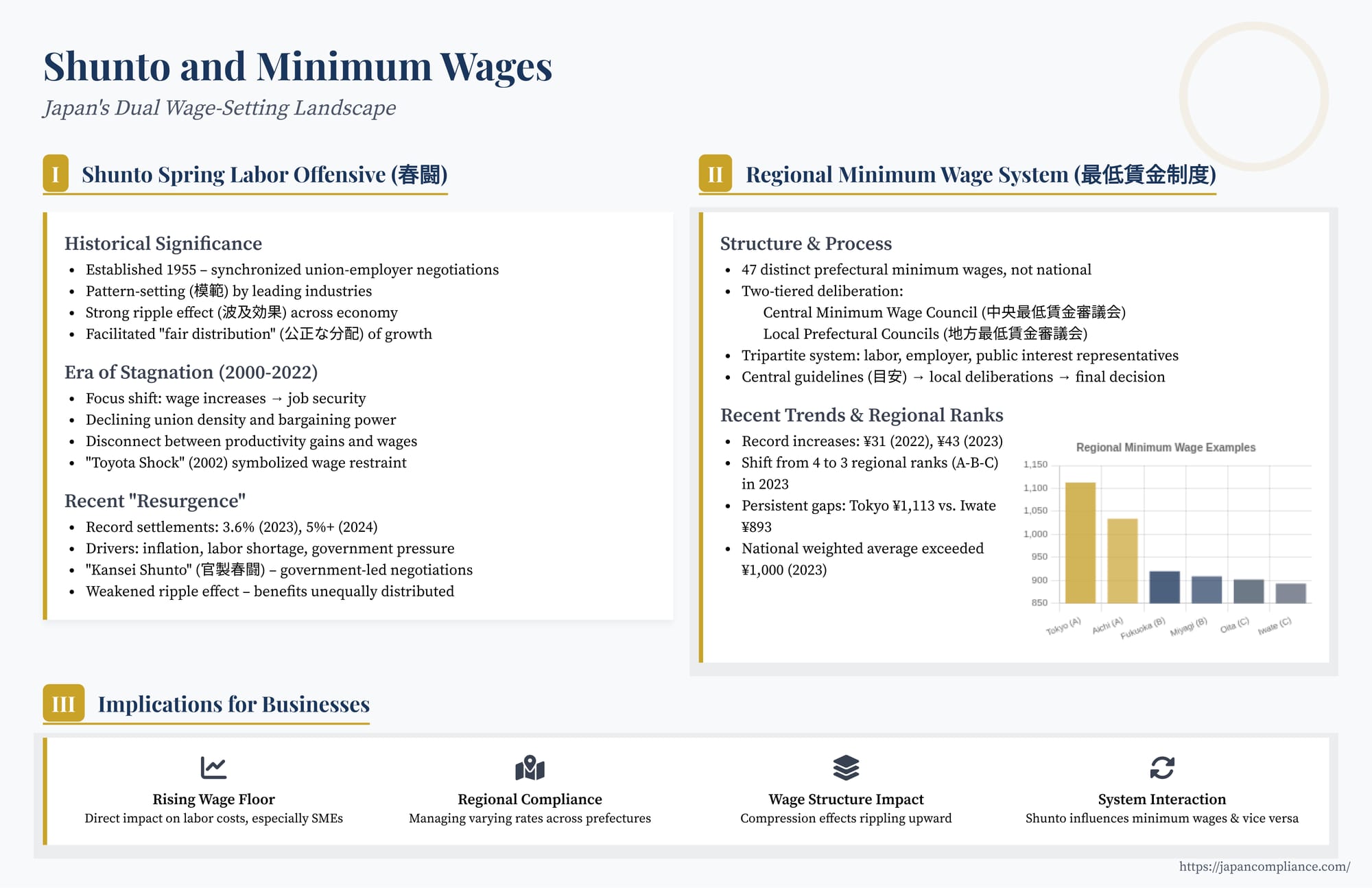

- Japan’s wage landscape now hinges on two forces: revived Shunto negotiations delivering record union wage hikes and rapid prefectural minimum-wage increases.

- Shunto’s ripple effect is weakening, while the regional minimum-wage system exerts growing pressure—especially on SMEs in lower-wage prefectures.

- Businesses must track both mechanisms to budget labour costs, adjust internal pay scales and ensure nationwide compliance.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: A New Dawn for Wages in Japan?

- Part 1: Shunto (春闘) – The Spring Offensive and its Changing Role

- Part 2: Japan's Regional Minimum Wage System (最低賃金制度)

- Conclusion: A Dual System in Flux

Introduction: A New Dawn for Wages in Japan?

After nearly three decades of stagnation, wages in Japan are suddenly a major topic of discussion. Triggered by global inflationary pressures and a strong push from the government, recent years have witnessed headline-grabbing wage increases negotiated during the annual Shunto spring labor offensive, alongside record hikes in prefectural minimum wages. For foreign businesses operating in Japan, understanding the mechanisms that influence wage levels – both the traditional, union-led Shunto and the government-mandated minimum wage system – is crucial for talent acquisition, compensation planning, and overall business strategy.

Are the recent high wage settlements a sign that Shunto is regaining its former power to set broad societal wage norms? How does Japan's complex regional minimum wage system function, and what are the implications of its recent rapid increases, especially given persistent regional disparities? This article delves into these two core components of Japan's wage-setting landscape, exploring their history, current dynamics, and what they mean for businesses navigating the evolving Japanese labor market.

Part 1: Shunto (春闘) – The Spring Offensive and its Changing Role

Shunto, often translated as the "Spring Labor Offensive," is a uniquely Japanese institution dating back to 1955. It refers to the synchronized negotiation process where labor unions, primarily organized at the enterprise level but coordinated through industrial federations and national centers like RENGO (the Japanese Trade Union Confederation), collectively bargain with employers over annual wage increases and other working conditions, typically culminating in settlements during the spring months.

Shunto's Historical Significance: Setting the Pace

In Japan's post-war high-growth era, Shunto played a pivotal role far beyond securing raises for union members.

- Pattern Setting: Key unions in leading industries (historically steel, later automotive and electronics) acted as "pattern setters." Their negotiated wage increases served as benchmarks (sōba, 相場) that other unions, across different industries and company sizes, aimed to match.

- Ripple Effect (波及効果, hakyū kōka): Crucially, Shunto outcomes had a significant ripple effect throughout the economy. Non-unionized companies, particularly SMEs competing for labor, often felt compelled to follow the Shunto trend to attract and retain workers. Furthermore, Shunto results historically influenced public sector wages, agricultural price supports, social security benefit levels, and more, contributing to a broad-based improvement in living standards and income equality during that period.

- Fair Distribution: A core tenet of Shunto was the idea of achieving a "fair distribution" (公正な分配, kōsei na bunpai) of the fruits of economic growth, ensuring that productivity gains translated into higher wages for workers across the board.

The Era of Stagnation (c. 2000 – 2022)

The influence and impact of Shunto waned significantly from the late 1990s / early 2000s onwards.

- Shift in Priorities: Following the collapse of the bubble economy and subsequent economic stagnation, concerns about job security took precedence over wage demands for many unions. The focus shifted from securing substantial base wage increases (ベースアップ, bēsu appu, often shortened to ベア, bea) to merely maintaining existing wage structures (via automatic seniority-based increments, 定期昇給 teiki shōkyū or 定昇 teishō) and relying on lump-sum bonuses, which are more flexible for employers. The infamous "Toyota Shock" of 2002, where the leading automaker agreed to zero base-up despite record profits, symbolized this shift and set a precedent for widespread wage restraint.

- Declining Union Clout: Factors like declining union density, the rise of non-regular employment, and a greater focus on enterprise-specific issues weakened the solidarity and bargaining power underlying Shunto. National union centers like RENGO often refrained from setting ambitious, unified wage targets.

- Productivity-Wage Disconnect: As highlighted in government white papers and academic analyses, this period saw a marked divergence between Japan's labor productivity growth (which, while slower than the US, was comparable to some European countries like Germany) and wage growth, which remained largely flat. This led to a declining labor share of income and a corresponding increase in corporate profits, retained earnings, and shareholder dividends. Shunto, in this phase, failed in its traditional role of ensuring productivity gains were broadly shared.

The Recent "Resurgence" and "Kansei Shunto"

Starting around 2014, and accelerating dramatically in 2023 and 2024, Shunto wage settlements saw a notable uptick, breaking long-standing records.

- High Settlements: RENGO reported average wage increases (including the seniority increment portion) exceeding 3.6% in 2023 and over 5% in 2024 – levels unseen in decades. Major companies reported even higher figures.

- Key Drivers: This resurgence was fueled by a confluence of factors: persistent inflation eroding real wages, intensifying labor shortages making companies more willing to pay to attract talent, and unprecedentedly strong encouragement from the government. Prime Minister Kishida's administration actively engaged with business and labor leaders, urging significant wage hikes, leading to the term "kansei shuntō" (官製春闘) or "government-led Shunto."

- A New Phase? Does this signify a genuine revival of Shunto's power? Some argue it marks a potential turning point, breaking the deflationary mindset. However, skepticism remains. The high increases coincide with high inflation, meaning real wage gains are still lagging for many. Furthermore, the heavy government involvement raises questions about whether the momentum is sustainable without continued political pressure.

- Weakening Ripple Effect: Perhaps most critically, evidence suggests the broad societal ripple effect of Shunto has significantly diminished. While unionized workers in large, profitable firms secured substantial raises, analyses indicate these gains are not automatically spreading to non-unionized firms or SMEs to the extent they once did. Wage dispersion between firms appears to be increasing. This suggests that while Shunto still plays a role for organized labor, its function as a mechanism for economy-wide wage norm setting and equitable distribution may have fundamentally weakened. If recent gains primarily benefit already advantaged workers, it could exacerbate rather than reduce overall wage inequality.

Part 2: Japan's Regional Minimum Wage System (最低賃金制度)

While Shunto influences negotiated wages, the legal wage floor in Japan is set by the Minimum Wage System (最低賃金制度, saitei chingin seido), governed by the Minimum Wage Act (最賃法, Saichinhō).

Structure: Prefectural, Not National

Unlike countries with a single national minimum wage, Japan sets 47 distinct regional minimum wages (地域別最低賃金, chiikibetsu saitei chingin), one for each prefecture. These regional minimums apply universally to all employees within that prefecture, regardless of industry (though separate, typically higher, industry-specific minimums can also be set for certain sectors).

The Deliberation Process: A Unique Tripartite System

The process for determining the annual revisions to these regional minimum wages is unique and involves a two-tiered council structure:

- Central Minimum Wage Council (中央最低賃金審議会, Chūchin): Located within the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), this council comprises representatives from labor unions, employer associations, and the public interest (academics, experts). Each summer (typically culminating in late July), following a formal request (諮問, shimon) from the MHLW Minister, the Central Council deliberates and proposes a non-binding guideline (目安, meyasu) for the amount of increase (e.g., "increase by X yen") appropriate for different regions. It does not set the actual minimum wage levels.

- Local (Prefectural) Minimum Wage Councils (地方最低賃金審議会, Jichin): Each prefecture has its own tripartite council. These local councils receive the central guideline amount relevant to their region. They then conduct their own deliberations, taking into account the guideline plus local conditions – specifically, worker living costs, prevailing wages in the prefecture, and the capacity of local businesses to pay wages (as mandated by Article 9(2) of the Minimum Wage Act). Based on this, each local council recommends a specific minimum wage level (in JPY per hour) for its prefecture.

- Final Decision: The recommendation from the local council is submitted to the Director of the Prefectural Labour Bureau (an MHLW agency), who, after soliciting public comment, formally decides and announces the new regional minimum wage, usually taking effect from October 1st.

The Guideline (Meyasu) System and Regional Ranks

The annual guideline from the Central Council is a key feature:

- Purpose: Introduced in 1978 after all prefectures had established minimum wages, the meyasu system aims to provide a national reference point to ensure some degree of consistency and facilitate timely revisions across the 47 prefectures.

- Regional Ranking: Since its inception, the system has grouped prefectures into ranks based on their overall economic conditions (considering factors like income levels, consumer prices, business activity). Historically, there were four ranks (A, B, C, D). Different guideline increase amounts were recommended for each rank, with higher-ranked (more economically robust) prefectures generally receiving larger recommended increases.

- Shift to 3 Ranks (A-B-C) in 2023: Recognizing that underlying economic disparities between regions had narrowed somewhat over decades, while minimum wage level gaps had actually widened, the Central Council agreed in 2023 to consolidate the system into three ranks (A, B, C). Rank A still includes major metropolitan areas like Tokyo, Kanagawa, and Osaka. Rank B became much larger, encompassing many mid-tier prefectures, while Rank C comprises prefectures with generally lower wage levels. This change was intended, in part, to moderate the widening gap between the highest and lowest minimum wages by reducing the number of differential increase recommendations.

- "Public Member Opinion": Due to often significant divergence between labor and employer representatives' positions on the appropriate increase amount, the Central Council frequently fails to reach a unanimous consensus on the guideline. In such cases, a practice has developed where the public interest members issue a compromise proposal as a "Public Member Opinion" (公益委員見解, kōeki iin kenkai). While labor and employer members may formally dissent, they typically agree to transmit this opinion to the local councils as the official guideline for that year.

Recent Trends: Record Hikes and Persistent Gaps

In recent years, mirroring the Shunto trend, minimum wage increases have accelerated:

- High Guideline Increases: The central guideline recommended record average increases in both 2022 (JPY 31) and 2023 (JPY 41, leading to a weighted average of JPY 43 after local adjustments). The 2024 guideline was also expected to be substantial.

- Local Councils Exceeding Guidelines: Particularly in 2023, many local councils in lower-ranked prefectures (Ranks B and C) recommended increases larger than the central guideline suggested for their rank. This reflects a strong push at the local level to close the regional wage gap more quickly. For example, some Rank C prefectures saw increases of JPY 45-47, significantly above the JPY 39 guideline for that rank.

- Persistent Disparity: Despite these efforts, a considerable gap remains between the highest (Tokyo, JPY 1113 in FY2023) and lowest (Iwate, JPY 893 in FY2023) minimum wages – a difference of JPY 220 per hour. While the ratio of lowest-to-highest has improved slightly (reaching just over 80%), bridging this gap remains a major policy challenge.

- The "National Average" Figure: Media reports often highlight the "national weighted average" minimum wage (calculated by weighting each prefecture's minimum wage by its workforce size), which surpassed JPY 1000 for the first time in 2023. While a useful indicator, it's crucial to remember that this average is heavily influenced by the high wages and large populations in Rank A regions; the majority of prefectures have minimum wages below this average.

- Link to Public Assistance: Article 9(3) of the Minimum Wage Act requires consideration of consistency with public assistance (生活保護, seikatsu hogo) levels. Historically, when minimum wages fell below welfare levels in some regions, special adjustments were made via the guideline system to rectify this "reversal phenomenon." This linkage ensures the minimum wage functions as a meaningful work incentive relative to welfare.

Implications for Businesses

- Rising Wage Floor: The rapid increases in regional minimum wages directly impact labor costs, particularly for businesses employing workers at or near the minimum wage, common in sectors like retail, hospitality, and care services, and especially affecting SMEs in lower-wage prefectures.

- Compliance Across Regions: Companies operating in multiple prefectures must track and comply with varying minimum wage rates and effective dates.

- Impact on Wage Structures: Increases at the bottom can create pressure to adjust wages further up the scale to maintain internal wage differentials ("compression effect").

- Planning and Budgeting: Businesses need to anticipate continued upward pressure on minimum wages and factor this into budgeting, pricing (cost pass-through challenges), and potentially investments in automation or productivity improvements.

- Shunto vs. Minimum Wage: While distinct, the two systems interact. High Shunto settlements can create political momentum for larger minimum wage increases. Conversely, significant minimum wage hikes can influence Shunto demands, especially in lower-paying sectors. Businesses need to monitor both.

Conclusion: A Dual System in Flux

Japan's wage landscape is shaped by the interplay between the collective bargaining outcomes of Shunto and the legally mandated regional minimum wage system. While recent years have seen historically high increases in both arenas, driven by economic pressures and government policy, their underlying effectiveness and future trajectory remain subjects of debate.

Shunto's role appears to be shifting – while still significant for major unionized firms, its power to set broad societal norms and ensure equitable distribution across the economy seems diminished compared to its past. The recent high settlements may be more a reaction to immediate economic conditions than a sign of restored systemic influence.

Meanwhile, the regional minimum wage system is playing an increasingly important role as a rising wage floor, particularly impacting SMEs and lower-wage regions. The recent move to consolidate regional ranks signals an attempt to address disparities, but significant gaps persist, and the system's complex deliberation process continues.

For businesses operating in Japan, this dual system requires careful monitoring. Shunto outcomes remain relevant market signals, while minimum wage regulations represent binding legal obligations with significant cost implications. Navigating this evolving landscape requires understanding the distinct functions, limitations, and recent trends of both mechanisms to formulate effective compensation strategies, manage labor costs, and ensure compliance across Japan's diverse regional economies.

- Wage Claims for Non-Working Shift Workers in Japan: Understanding Employer Obligations

- Managing Your Japanese Workforce: Navigating Retirement Benefits and Wage Claims

- Navigating Japan's "2024 Problem": Work Style Reforms and Their Impact on Business

- MHLW Labour Standards Bureau: Minimum Wage System Overview

- Tokyo Regional Minimum Wage 2024 Leaflet (PDF, MHLW)