Shipping Valuables on the Cheap: Can a Parcel Service's Liability Cap Bind the Owner if They Weren't the Shipper?

Low-cost parcel delivery services (takuhai-bin in Japan) are a modern marvel of logistics, offering speed and affordability for shipping a vast array of goods. To maintain these low prices, carriers typically operate under standard contract terms (yakkan) which almost invariably include clauses limiting their liability for lost or damaged items to a relatively modest fixed sum, unless a higher value is declared and a correspondingly higher fee is paid. These terms also often restrict the carriage of extremely valuable items, like jewelry.

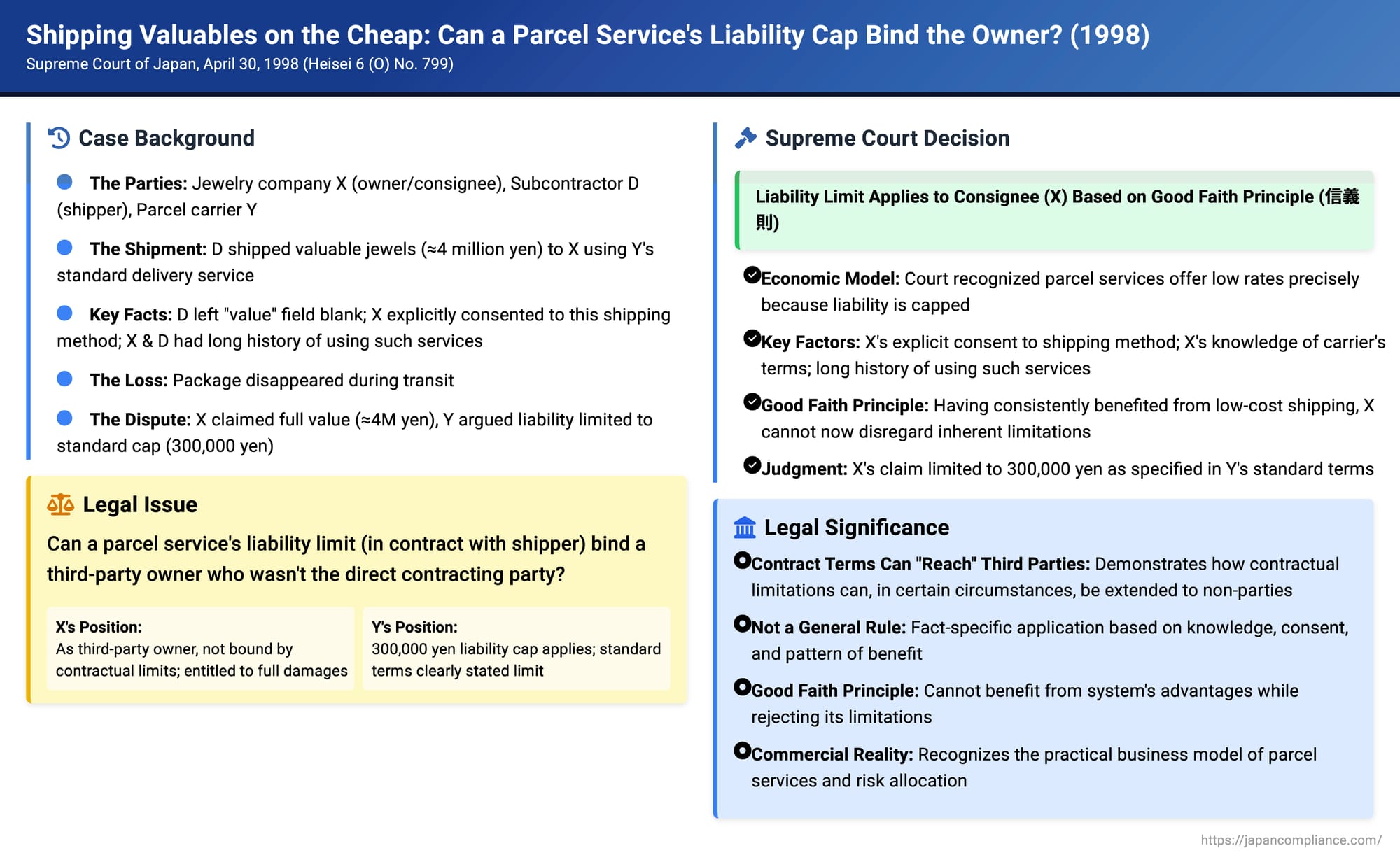

But what happens if, for example, a jewelry business (the owner) has its subcontractor ship valuable jewels back to them using such a standard, low-cost parcel service, the subcontractor doesn't declare the true value (or leaves the value field blank), and the parcel is lost? Can the owner, who wasn't the direct party to the shipping contract with the carrier, claim the full multi-million yen value of their lost jewels? Or is their claim, too, capped by the carrier's standard low liability limit (e.g., 300,000 yen)? This complex question, touching on privity of contract, tort liability, and the principle of good faith, was addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a significant judgment on April 30, 1998 (Heisei 6 (O) No. 799).

Parcel Delivery Services: The Trade-Off Between Convenience, Cost, and Liability Limits

Parcel delivery services have revolutionized how goods are moved, offering a convenient and economical option for businesses and individuals alike. Their business model is predicated on handling a high volume of small to medium-sized packages, processed and transported rapidly through standardized systems. Key to this model are:

- Low Freight Charges: Attracting a broad user base.

- Standardized Terms of Carriage (Yakkan): These are non-negotiable terms that govern the relationship between the shipper (consignor) and the carrier.

- Liability Limitations: A crucial part of these terms is a pre-determined limit on the carrier's financial liability in case of loss or damage to a parcel. This limit is usually a fixed, relatively low amount (e.g., 300,000 yen, which was approximately $2,500-$3,000 USD at the time of the case, a common limit then and often similar today for basic services).

- Declared Value Options (and Restrictions): Senders usually have the option to declare a higher value for their goods and pay an increased freight charge for enhanced liability coverage, but carriers also typically reserve the right to refuse to carry items exceeding a certain declared value or specific categories of high-risk/high-value goods like jewelry through their standard service.

These liability limitations are not arbitrary; they are an integral part of what allows carriers to offer low standard shipping rates. They represent a risk allocation: the carrier accepts a limited risk for a low price, and the shipper, by choosing the standard service for valuable items without declaring their true value, effectively assumes the risk of loss beyond that limit.

Facts of the 1998 Case: Lost Jewels and a Disputed Liability Cap

The case before the Supreme Court involved the loss of valuable jewels during parcel shipment:

- The Parties:

- X Company: A jewelry wholesaler, seller, and processor (the consignee, i.e., the intended recipient and effective owner of the lost jewels; plaintiff/appellant).

- Y Carrier: The parcel delivery service operator (defendant/appellee).

- D: A subcontractor who performed jewelry processing work for X Company (the consignor who handed the package to Y Carrier).

- The Background and Shipment: X Company had outsourced the processing of a valuable diamond (originally sold by X to another company, then given back to X by the ultimate buyer for custom work) and a red stone to its long-term subcontractor, D. After completing the processing, D needed to ship these finished jewels back to X Company.

- Using Y Carrier's Service: D opted to use Y Carrier's standard parcel delivery service for this shipment. When filling out the consignment note (waybill), D left the "description of goods" and "value" fields blank. Y Carrier's standard terms and conditions clearly stipulated a liability limit of 300,000 yen per parcel. The consignment note forms themselves had printed warnings stating that the value of the goods should be declared, that Y Carrier would not accept items valued over 300,000 yen for its standard service, and that it could not be held responsible for damages beyond the limit for such undeclared high-value items. Y Carrier also had stated restrictions on accepting jewelry.

- A Long-Standing Practice and Consignee's Consent: X Company and D had a well-established business relationship spanning approximately 16 years. During this time, they had frequently used various parcel delivery services, including Y Carrier's, to send valuable jewelry items to each other. For this particular shipment, D had informed X Company in advance that Y Carrier's service would be used, and X Company had explicitly consented to this shipping method.

- The Loss: D handed the package containing the jewels to Y Carrier's local agent. The package was transported to Y Carrier's sorting facility but subsequently disappeared and was deemed lost. The precise cause of the loss could not be determined.

- X Company's Compensation and Lawsuit: As X Company was unable to return the processed jewels to their original owners (its clients), it compensated them for their full value – approximately 3.84 million yen for the diamond and 100,000 yen for the red stone. X Company then, arguing that it had acquired the original owners' tort claims against Y Carrier for the negligent loss of the goods, sued Y Carrier for the full amount of nearly 4 million yen. X Company's position was that as a third-party owner, not a direct signatory to the carriage contract between D and Y, its claim in tort should not be restricted by the 300,000 yen contractual liability limit.

- The Appellate Court's Reasoning: The lower appellate court had acknowledged that generally, a consignor (D) might have concurrent claims against a carrier (Y) for both breach of contract and tort (negligence). It also recognized that contractual liability limitations often do not automatically apply to tort claims. However, it reasoned that the relationship between the direct contracting parties (D and Y) should primarily be governed by contract law to prevent the consignor from simply using a tort claim to bypass agreed-upon contractual limitations. Critically, for X Company (the third-party consignee/owner), the appellate court found that X Company was "substantially identifiable" with the consignor D, given their close business relationship and X's explicit consent to D's use of Y Carrier's service for this shipment. Therefore, the court concluded that contract law principles, including the 300,000 yen liability limitation, should apply by analogy to X Company's tort claim. Thus, it limited X's recovery to 300,000 yen.

X Company appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Consignee Bound by Liability Limit Based on the Principle of Good Faith

The Supreme Court dismissed X Company's appeal, agreeing that its claim was limited to 300,000 yen. However, the Supreme Court employed a different, more direct line of reasoning, focusing on the overarching principle of good faith (shingi-soku or 信義則), a fundamental concept in Japanese contract law that requires parties to act honestly and fairly towards each other.

- Reasonableness of Liability Limits in Parcel Delivery Services: The Court first affirmed the commercial reasonableness of liability limitation clauses in the context of parcel delivery services. It recognized that these services are designed to offer "low-cost freight for the rapid delivery of a large volume of small parcels," providing significant convenience to users. While carriers are expected to transport goods safely, reliably, and promptly, the very nature of this low-cost, high-volume model means that users must implicitly accept certain operational constraints. Limiting liability to a pre-determined, relatively low sum (unless the carrier is guilty of intent or gross negligence) is a rational way for carriers to keep their standard freight charges as low as possible and manage the risks inherent in such an operation.

- Liability Limit Applies to Consignor's Tort Claim (as well as Contract Claim): The Supreme Court then stated that given the purpose of these liability limits (i.e., to enable the provision of low-cost services), it should be understood as the "rational intent" of the contracting parties (the consignor D and the carrier Y) that such a limit applies not only to claims based on breach of the carriage contract but also to any tort claims the consignor might bring against the carrier for the same loss. If the limit did not apply to tort claims, its purpose would be easily nullified by the consignor simply framing their claim in tort instead of contract. The Court also noted that this does not unduly prejudice the consignor, because if the loss or damage is caused by the carrier's intentional misconduct or gross negligence, the consignor can still claim full damages (as was typically provided in such standard terms, including Y Carrier's here).

- Extension of the Liability Limit to the Consignee (X Company) via the Principle of Good Faith: This was the core of the Supreme Court's decision regarding X Company's claim as a third party. The Court reasoned as follows:

- Considering the specific characteristics of parcel delivery services, the purpose behind establishing liability limits, and the fact that Y Carrier's standard terms themselves (in a clause regarding damage assessment) took into account circumstances affecting the consignee, it is appropriate to conclude that:

- A consignee (like X Company), at least when they have knowingly consented to their goods being transported by such a parcel delivery service, is barred by the principle of good faith from demanding damages from the carrier that exceed the carrier's pre-determined contractual liability limit.

- X Company's Conduct and the Application of Good Faith: The Court then applied this good faith principle to X Company's specific situation:

- X Company was well aware that if the true nature (jewels) and high value of the items were accurately declared, Y Carrier (or other similar parcel services) would likely not accept them for shipment under their standard, low-cost service.

- X Company and D had a long and frequent history of using such parcel delivery services to ship valuable jewelry to each other, thereby consistently taking advantage of the significantly lower freight charges these services offered (compared to specialized, insured transport for high-value goods).

- For this particular lost shipment, X Company had not merely been aware that it was being sent by a standard parcel service but had explicitly consented to D's use of Y Carrier's service.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded, for X Company, having consistently benefited from the low-cost shipping model (which is viable precisely because of such standard liability limitations for undeclared high-value items), to now attempt to claim the full, multi-million yen value of the lost jewels from Y Carrier—far exceeding the 300,000 yen limit—would be contrary to the principle of good faith. X Company, by its conduct and consent, had effectively accepted the risk framework inherent in the service it chose to utilize.

Consequently, X Company's claim was limited to the 300,000 yen stipulated in Y Carrier's standard terms and conditions.

Significance: When Contract Terms Can "Reach" and Bind Third Parties

This 1998 Supreme Court decision is highly significant for illustrating how contractual terms, specifically a limitation of liability clause, can be effectively extended to bind a third party who was not a direct signatory to the contract.

- Not a General Rule of Third-Party Binding: It is crucial to understand that this case does not establish a broad principle that all contractual liability limitations automatically bind all potential third-party claimants in all circumstances.

- A Fact-Specific Application of Good Faith: The Supreme Court's reasoning was carefully and narrowly tethered to the specific facts and the equities of the situation:

- The particular nature and societal utility of parcel delivery services and the acknowledged commercial reasonableness of their standard liability limits, which are fundamental to their low-cost operational model.

- The third party's (X Company's) actual knowledge of the nature of the service, its typical limitations regarding high-value items, and its explicit consent to its use for their valuable goods under conditions that effectively bypassed those limitations (i.e., non-declaration of value).

- X Company's history of benefiting from the low-cost structure of such services, a structure made possible by these very liability limitations.

The decision highlights that if a third party knowingly consents to and benefits from a contractual arrangement between two other parties, and that arrangement includes inherent limitations that are essential to the benefits being provided, that third party may be prevented by the principle of good faith from later trying to act in a way that disregards those limitations when seeking a remedy.

Distinction from the Lower Appellate Court's Reasoning

It is also noteworthy that while the Supreme Court reached the same monetary outcome as the appellate court (limiting X's claim to 300,000 yen), its legal reasoning took a different path. The appellate court had focused on X Company being "substantially identifiable" with the consignor D and had applied contract law principles (including the limitation clause) to X's tort claim by way of analogy. The Supreme Court, however, based its extension of the limit to X Company more directly and compellingly on the overarching principle of good faith, focusing on X Company's own conduct, knowledge, and the benefits it had consistently derived from the shipping system whose limitations it now sought to ignore.

Conclusion

The 1998 Supreme Court decision in the case of the lost jewels serves as an important illustration of how the fundamental principle of good faith (shingi-soku) can operate within Japanese contract and tort law to achieve equitable and commercially sensible outcomes. It demonstrates that a third party who knowingly and willingly participates in and benefits from a service offered under specific contractual terms—including limitations of liability that are integral to that service's nature and cost structure—may be barred from later claiming damages in a manner that disregards those very terms. In the context of standardized, high-volume services like parcel delivery, where liability caps are a well-understood component of the low-cost offering, one cannot always expect to enjoy the economic advantages of the system while simultaneously rejecting its inherent and often necessary limitations when a loss occurs, especially if one has knowingly sidestepped the procedures for declaring and protecting high-value items.