Shifting Grounds: Can Tax Authorities Change Reasons for Reassessment Mid-Lawsuit in Japan?

Date of Judgment: July 14, 1981

Case Name: Claim for Revocation of Corporate Tax Reassessment Disposition (昭和52年(行ツ)第62号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

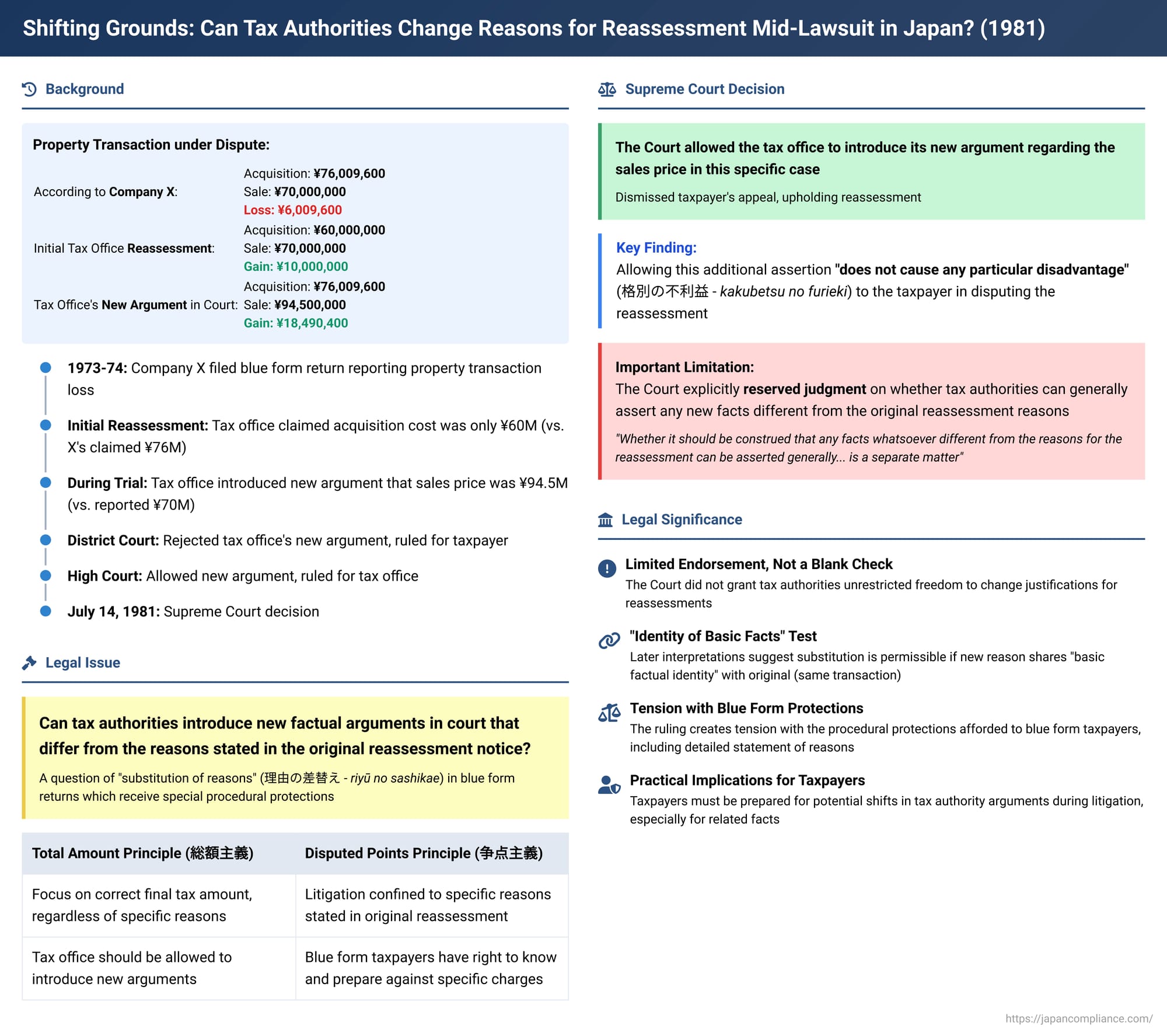

In a significant judgment on July 14, 1981, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed a contentious issue in tax litigation: whether tax authorities, when defending a tax reassessment in court, can introduce new factual arguments or reasons to justify that reassessment if those new justifications differ from the ones provided in the original reassessment notice. This issue, often termed "substitution of reasons" (理由の差替え - riyū no sashikae), is particularly critical for taxpayers filing under Japan's "blue form return" (青色申告 - aoiro shinkoku) system, which offers certain procedural protections, including the right to a detailed statement of reasons for any reassessment.

The Disputed Property Transaction: From Loss to Gain (in Tax Office's View)

The plaintiff, Company X, was a corporation engaged in the real estate business and filed its corporate tax returns using the blue form. In its return for the fiscal year Showa 48 (approximately 1973-1974), X reported a transaction involving a piece of real estate ("the subject property"). X declared that it had acquired this property for ¥76,009,600 and subsequently sold it for ¥70,000,000, thereby claiming a loss of approximately ¥6 million on the transaction.

The head of the competent tax office, Y, reviewed X's return and issued a corrective reassessment. The tax office disputed X's calculation, primarily asserting that the correct acquisition cost of the subject property was only ¥60,000,000, not the ~¥76 million claimed by X. Based on this lower acquisition cost and the reported sales price of ¥70,000,000, the tax office determined that X had actually realized a capital gain of ¥10,000,000 from the transaction, rather than a loss. This, along with other adjustments, formed the basis of the reassessment, and the notice provided to X cited the incorrect acquisition cost as a key reason.

X filed a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of this reassessment, arguing that its originally reported acquisition cost of ~¥76 million was correct and that it had, therefore, incurred a loss.

During the first instance trial, the tax office (Y) introduced a new, alternative argument to defend its reassessment – "the subject additional assertion." Y contended that even if X's claimed acquisition cost of approximately ¥76 million were accepted as correct, the actual sales price of the subject property was not the ¥70 million reported by X, but rather a significantly higher ¥94.5 million. Therefore, Y argued, even using X's acquisition cost figure, the transaction still resulted in a taxable capital gain of over ¥18 million (¥94.5 million sales price minus ~¥76 million acquisition cost). Since this gain exceeded the ¥10 million gain upon which the original reassessment was based, Y asserted that the reassessment, in its final tax amount, was ultimately lawful and should be upheld, regardless of the correctness of the initially stated reason concerning the acquisition cost.

The first instance court (Kyoto District Court) rejected this additional assertion by the tax office. It held that the requirement for a detailed statement of reasons for reassessments made to blue form returns (under Article 130, paragraph 2 of the Corporate Tax Act) implies that the tax office should not be permitted to use facts different from those stated in the original notice to justify its reassessment in court. Based on finding X's original acquisition cost claim to be correct, the District Court partially cancelled the reassessment.

However, the Osaka High Court, on appeal, reversed the District Court's decision. The High Court took the view that a lawsuit to cancel a tax reassessment is, in substance, akin to a lawsuit seeking confirmation of the non-existence of the tax debt itself. Therefore, the factual dispute before the court should be about the correct amount of the taxpayer's income for the period, not merely about the validity of the specific reasons provided by the tax office in its initial reassessment notice. The High Court reasoned that as long as the reasons initially provided in the notice met the minimum requirements of informing the taxpayer and preventing arbitrary administrative action, the tax office should be allowed to introduce new factual arguments or legal theories in court to support the overall correctness of the final assessed tax amount. It thus permitted Y's additional assertion regarding the higher sales price and, after considering it, dismissed X's claim, finding that the overall reassessed tax amount was justified. X appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Battle: Can the Tax Office Change Its Story in Court?

The central legal issue was the permissibility of "substitution of reasons" by the tax authorities in litigation concerning blue form tax returns. Specifically:

- Is the tax office strictly bound in court by the factual and legal grounds articulated in the "statement of reasons" attached to its original reassessment notice?

- Or can the tax office, if its initial reasons are challenged or found wanting, introduce new or alternative factual bases to demonstrate that the final tax amount assessed was nonetheless correct?

This question involves a tension between:

- The procedural protections afforded to blue form taxpayers, which include the right to a clear statement of reasons for any reassessment, enabling them to prepare their defense.

- The principle that tax litigation should ultimately determine the correct tax liability based on substantive law and true facts (often referred to as the "total amount principle" - 総額主義 sōgakushugi, where the lawsuit concerns the overall tax amount).

- The opposing "issue-specific principle" or "disputed points principle" (争点主義 - sōten-shugi), which would confine the litigation more strictly to the specific reasons and issues raised in the administrative disposition.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Substitution Allowed if No "Particular Disadvantage" to Taxpayer

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision that allowed the tax office to introduce its additional assertion regarding the sales price.

The Supreme Court's reasoning was concise:

- The Court acknowledged the tax office's (Y's) new argument: "even if the acquisition cost of the subject real property was ¥76,009,600, its sales price was ¥94,500,000; therefore, in any event, the subject reassessment disposition is lawful."

- The Key Finding: The Supreme Court held that allowing Y to make this "additional assertion" in court "does not cause any particular disadvantage (格別の不利益 - kakubetsu no furieki) to X (the taxpayer being reassessed) in disputing the said reassessment."

- Reservation on General Rule: Importantly, the Supreme Court explicitly reserved judgment on the broader question of whether, as a general rule in lawsuits challenging reassessments of blue form returns, the tax authority can assert any and all facts different from the reasons initially stated in the reassessment notice. The Court stated: "whether it should be construed that any facts whatsoever different from the reasons for the reassessment can be asserted generally in a lawsuit for revocation of a reassessment made with respect to a blue form return is a separate matter."

- Conclusion in the Specific Case: However, in this particular instance, the Court found that allowing Y to present its additional argument regarding the sales price was not prejudicial to X. Therefore, the High Court's decision to permit this additional assertion and ultimately uphold the reassessment was "justifiable in its conclusion."

- The Supreme Court also stated that this interpretation did not conflict with its prior ruling in a Showa 47 (1972) case (Supreme Court, December 5, 1972, Minshu Vol. 26, No. 10, p. 1795), which had established that defects in the statement of reasons in an original disposition are not cured by reasons provided in a subsequent administrative appeal decision. This implies that the issue here was not about curing a defective initial reason, but about the scope of permissible arguments in court.

Analysis and Implications: A Cautious Approach to "Substitution of Reasons"

This 1981 Supreme Court decision is a significant, though cautiously worded, precedent concerning the "substitution of reasons" in tax litigation in Japan:

- Limited Endorsement of Substitution, Not a Blank Check: The Supreme Court did not grant tax authorities unrestricted freedom to change their justifications in court when defending reassessments on blue form returns. The ruling was explicitly limited to the facts of the case, based on the finding of "no particular disadvantage" to the taxpayer. The Court's express reservation on the general applicability indicates its awareness of the potential for such substitutions to undermine taxpayer protections.

- The "Identity of Basic Facts" (基本的事実の同一性 - kihonteki jijitsu no dōitsusei) Criterion: Although not explicitly stated by the Supreme Court in this judgment, legal commentary and subsequent lower court jurisprudence have often interpreted this decision (and others) as implicitly supporting, or at least being consistent with, the idea that substitution of reasons by the tax authority is more likely to be permissible if the new reason shares a "basic factual identity" with the original reasons. In this case, both the tax office's original argument (about the acquisition cost) and its new argument (about the sales price) pertained to the calculation of capital gains from the very same property transaction. If the tax office had attempted to introduce an entirely unrelated income item or a completely different transaction as justification, the "no particular disadvantage" test might have yielded a different result.

- Tension with Blue Form Protections Remains: The blue form system is designed to offer taxpayers greater certainty and protection against arbitrary assessments, partly through the requirement for a clear statement of reasons. Allowing tax authorities significant latitude to substitute reasons in court could be seen as eroding this protection, as taxpayers prepare their legal challenges based on the reasons officially provided. The Supreme Court's cautious phrasing and its specific reliance on the "no particular disadvantage" standard reflect an attempt to balance the need for accurate tax determination with these procedural safeguards.

- Practical Considerations for Taxpayers: This ruling means that taxpayers challenging blue form reassessments must be prepared for the possibility that the tax authority might introduce new or alternative factual arguments to support the assessed tax amount, especially if those arguments are closely related to the originally disputed transaction. Taxpayers and their representatives need to be ready to address such shifts in the litigation.

- Potential Impact of Later Procedural Reforms: As noted by legal commentators, amendments to Japan's General Act of National Taxes in 2011 (effective 2013), which explicitly incorporated principles from the Administrative Procedure Act regarding the requirement for administrative agencies to provide reasons for their dispositions, might influence how courts view the adequacy of initial reasons and the permissibility of subsequent substitutions in current and future cases. These reforms generally aim to strengthen procedural transparency and fairness for individuals dealing with administrative agencies.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1981 decision in this case offers a nuanced perspective on the complex issue of "substitution of reasons" by tax authorities in lawsuits challenging reassessments of blue form tax returns. While not providing a general, unrestricted approval for tax authorities to change their justifications mid-litigation, the Court permitted the introduction of new, factually related arguments by the tax office in this specific instance, based on a finding that doing so caused no "particular disadvantage" to the taxpayer. This ruling highlights the ongoing judicial effort to balance the tax authority's objective of correctly assessing and collecting tax with the taxpayer's right to a fair, predictable, and adequately reasoned administrative process, especially under the protective umbrella of the blue form tax return system. The precise boundaries of permissible reason substitution, particularly concerning the "identity of basic facts," continue to be shaped by subsequent case law and legal scholarship.