Sharing the Shield: How Are Life Insurance Proceeds Divided Among 'Heir' Beneficiaries in Japan?

Date of Judgment: July 18, 1994

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Case No. 1993 (o) of 1991 (Insurance Claim Case)

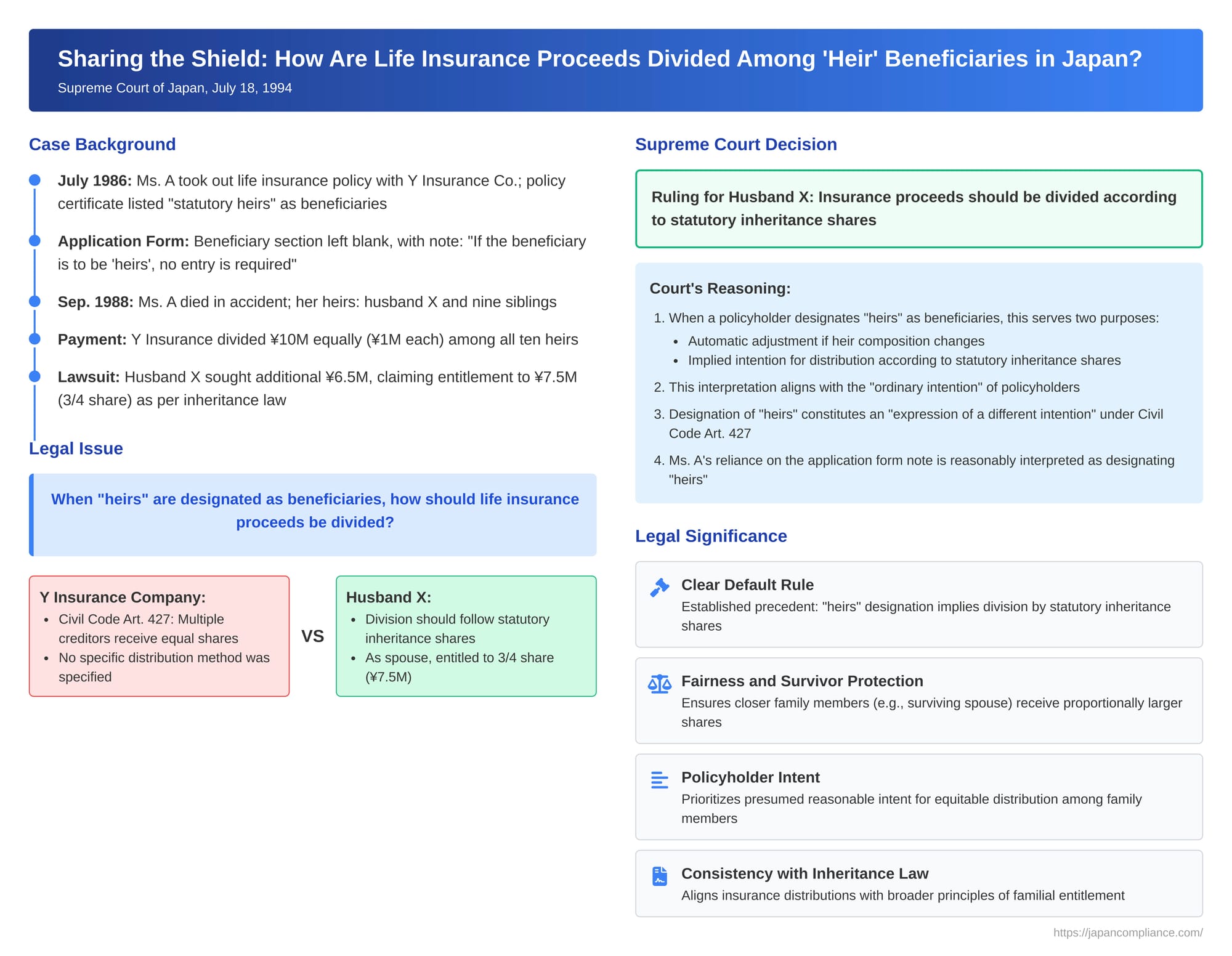

A common practice in life insurance is for the policyholder to designate their "heirs" (相続人 - sōzokunin) as the beneficiaries of the death benefit. While this seems like a straightforward way to ensure family members receive the proceeds, it can lead to a significant legal question when there are multiple heirs: how should the insurance money be divided among them? Should each heir receive an equal share, or should the proceeds be distributed according to their respective statutory inheritance proportions (法定相続分 - hōtei sōzokubun)? This critical issue was clarified by the Supreme Court of Japan in a landmark decision on July 18, 1994.

A Family's Claim, A Legal Question: Facts of the Case

The case involved Ms. A, who, on July 1, 1986, took out an installment savings women's insurance policy with Y Insurance Company (the defendant and respondent). Ms. A was the insured. The policy provided for an accidental death benefit of 10 million yen and had a term of five years.

Regarding the beneficiary designation, the insurance policy certificate itself stated "statutory heirs" (法定相続人). The application form for the policy had its beneficiary section left blank, but this section included a crucial note: "If the beneficiary is to be 'heirs', no entry is required."

Ms. A tragically died in an accident on September 28, 1988. At the time of her death, her statutory heirs consisted of her husband, X (the plaintiff and appellant in this Supreme Court case), and nine of Ms. A's siblings (or their successors by right of representation, if a sibling had predeceased Ms. A). This meant there were a total of ten statutory heirs.

Following Ms. A's death, all ten heirs, including her husband X, jointly filed a claim for the insurance proceeds with Y Insurance Company. Y Insurance Company proceeded to pay out the 10 million yen death benefit by dividing it equally among the ten heirs, with each heir receiving 1 million yen.

Mr. X disagreed with this equal division. He argued that Ms. A had, by her actions (relying on the application note), effectively designated her statutory heirs as beneficiaries. He contended that when "statutory heirs" are designated, the insurance proceeds should be distributed among them according to their respective statutory inheritance shares, as this would most closely align with the policyholder's reasonable intentions. Under Japanese inheritance law, Mr. X's statutory inheritance share as the surviving spouse (with the other heirs being siblings of the deceased) was three-fourths (3/4). He had received only 1 million yen but believed he was entitled to 7.5 million yen (3/4 of 10 million yen). Consequently, he filed a lawsuit against Y Insurance Company to recover the difference of 6.5 million yen.

Y Insurance Company countered that because the beneficiary was determined by the policy's terms (specifically, the note on the application form, rather than an explicit naming by Ms. A in the blank space), the general rule of Civil Code Article 427 should apply. This article stipulates that when multiple creditors have a divisible claim, they are each entitled to an equal share unless a different intention is expressed. Y also argued that even if Ms. A was considered to have designated "heirs," this designation alone did not constitute an "expression of a different intention" sufficient to override the default equal-share rule of Article 427 and mandate distribution by statutory inheritance shares.

The Tokyo High Court, hearing the case on appeal, found that the beneficiary section of the application form was indeed blank and noted the instruction that no entry was needed if heirs were to be the beneficiaries. The High Court concluded that Ms. A had not, in fact, actively designated a beneficiary. It further reasoned that even if her reliance on the note could be inferred as a designation of "heirs," this did not extend to specifying any particular proportion for their respective shares. Thus, the High Court rejected Mr. X's claim, implicitly upholding the equal distribution made by the insurer. Mr. X then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Divide: Equal Shares vs. Inheritance Proportions

The central legal issue was how to interpret a beneficiary designation of "heirs" in the context of distributing insurance proceeds among multiple heirs.

- Civil Code Article 427: This article provides a default rule for situations where several persons are entitled to a divisible claim (like a sum of money). It states that each person is entitled to an equal part, unless a different intention is expressed (別段ノ意思表示 - betsudan no ishi hyōji).

- The Core Question: Does a policyholder's designation of "heirs" as beneficiaries constitute such an "expression of a different intention" that displaces the default rule of equal shares and instead implies a division according to statutory inheritance proportions?

Prior to this 1994 Supreme Court decision, lower court rulings and even some Supreme Court pronouncements in slightly different contexts had varied:

- A 1965 Supreme Court decision (Showa 40.2.2, h74.pdf in the provided documents) had established that when "heirs" are designated as beneficiaries, the insurance proceeds become their proper property and do not form part of the deceased's general estate to be distributed via inheritance law. This meant the division among heirs was not automatically governed by inheritance rules for estate assets.

- A Tokyo District Court case in 1985 held that an explicit designation of "statutory heirs" led to division by inheritance shares.

- Conversely, a 1987 Tokyo District Court case ruled for equal shares where there was no beneficiary designation by the policyholder, and the policy terms themselves stipulated that the heirs would be the beneficiaries in such an event.

- The Supreme Court itself, in cases where a designated beneficiary had predeceased the insured and no new beneficiary was named (leading to heirs becoming beneficiaries by operation of law or policy terms), had previously leaned towards equal shares. For example, a 1992 Supreme Court decision based on policy terms and a 1993 Supreme Court decision (Heisei 5.9.7, h78.pdf in the provided documents) based on the old Commercial Code Article 676(2) both endorsed equal division among such subsequent heir-beneficiaries.

The facts of the 1994 case were seen as somewhat intermediate—not an explicit naming, but an implicit designation through reliance on the application form's instruction.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Ruling: "Heirs" Implies Inheritance Shares

The Supreme Court, in its July 18, 1994 judgment, reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. It held that when a policyholder designates "heirs" of the insured as the beneficiaries of a death benefit, this designation, in the absence of special circumstances indicating otherwise, is presumed to include an intention that the heirs should receive the insurance proceeds in proportions corresponding to their statutory inheritance shares.

The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Dual Purpose of Designating "Heirs": The Court opined that a policyholder's intention in designating "heirs" as beneficiaries typically serves two purposes:

- Firstly, it is to ensure that if changes occur in the composition of the individuals who would be the insured's heirs by the time the insured event (death) happens (e.g., due to births, deaths, marriages, divorces), the policyholder does not need to go through the trouble of formally changing the beneficiary designation each time. The individuals who are the legal heirs at the moment of the insured's death will automatically be the beneficiaries.

- Secondly—and this was the crucial part of the ruling—such a designation is also understood to include the intention that these heirs should acquire the insurance proceeds in proportions determined by their respective statutory inheritance shares.

- Alignment with Policyholder's "Ordinary Intention" and "Rationality": The Supreme Court found this interpretation to be consistent with the "ordinary intention" of a policyholder and also to be "rational".

- "Expression of a Different Intention" under Civil Code Art. 427: Consequently, when a policyholder designates "heirs" as beneficiaries and there are multiple such heirs, this act of designation is itself considered an "expression of a different intention" as contemplated by Civil Code Article 427. This "different intention" displaces the default rule of equal shares. The "different intention" expressed is precisely that the division should follow the inheritance proportions.

- Application to Mr. X's Case: The Court found that Ms. A, by leaving the beneficiary section of the application blank in reliance on the note that "If [the beneficiary is to be] heirs, no entry is required," could be reasonably inferred, according to common experience, to have thereby designated "heirs" as the beneficiaries of her life insurance policy. Based on the principles outlined above, this meant that Mr. X, as Ms. A's surviving spouse, was entitled to receive a portion of the 10 million yen death benefit corresponding to his statutory inheritance share, which was three-fourths (3/4).

The Supreme Court therefore quashed the High Court's decision. It remanded the case back to the High Court to consider Y Insurance Company's defense that it had already made payments to the ten heirs (1 million yen each) and whether such payments could be protected under the legal principles governing payment to a "quasi-possessor of a claim" (meaning Y might be discharged from liability to X to the extent of payments made in good faith to those who appeared to be rightful claimants of at least that portion).

Unpacking the "Ordinary Intention" and "Rationality"

The Supreme Court's emphasis on the "ordinary intention" of the policyholder and the "rationality" of interpreting "heirs" as implying inheritance-based shares is significant.

- Fairness and Survivor Protection: Distributing insurance proceeds according to statutory inheritance shares often leads to outcomes that are perceived as more equitable and better aligned with the typical needs of a deceased's family. For example, under Japanese inheritance law, a surviving spouse usually receives a substantial portion of the estate, reflecting their closer relationship and often greater dependence. Applying this same proportional division to life insurance proceeds intended for "heirs" generally supports the primary function of life insurance, which is often to provide for the financial security of surviving close family members.

- Consistency with General Inheritance Principles: Statutory inheritance shares represent a societal and legal default for how a person's general assets are distributed upon their death if they die intestate (without a will). The Supreme Court's decision suggests that when a policyholder uses the term "heirs" for insurance beneficiaries, they are likely thinking along these established lines of familial entitlement. This aligns the specific insurance context with broader principles of inheritance.

This approach was favored by many legal scholars who argued that the "equal shares theory" could lead to unfair results, especially when a surviving spouse (with a large statutory inheritance share) might receive only a small fraction of the insurance if there were many other heirs with smaller individual statutory shares (like distant siblings).

Distinguishing from Other Scenarios

The Supreme Court's 1994 decision specifically addresses the scenario where the policyholder makes a designation of "heirs". This is distinguished from situations where heirs become beneficiaries by other means, such as by operation of law or policy terms when a named beneficiary predeceases the insured and no new designation is made.

- As mentioned earlier, the Supreme Court in a 1993 case (Heisei 5.9.7, involving the old Commercial Code Art. 676(2)) had ruled that where heirs of a predeceased beneficiary became entitled to the proceeds by operation of law, they took in equal shares.

- The commentary surrounding the 1994 decision explains this difference by focusing on the source of the beneficiary status. If the policyholder actively designates "heirs," their presumed intent for proportional division is given effect. If, however, the law or policy terms simply provide a default fallback to "heirs" because no other effective designation exists, the policyholder's specific intent regarding division proportions is absent, and thus the general Civil Code rule of equal shares (Art. 427) applies. While this distinction is seen as logical, some scholars still critique the outcome of equal shares in the predeceased beneficiary context.

What if the policy terms themselves, rather than an active designation by the policyholder, state that "heirs" will be the beneficiaries if no one is named (similar to the 1987 Tokyo District Court case)? The legal commentary suggests that the rationale of the 1994 Supreme Court decision—focusing on the policyholder's presumed intent for a fair distribution aligned with inheritance principles—should arguably still lead to a division by inheritance shares, even in such cases.

Impact of a Will Specifying Different Inheritance Shares

The 1994 Supreme Court judgment did not need to address what would happen if the insured policyholder (Ms. A) had left a will specifying inheritance shares different from the default statutory ones (as permitted by Civil Code Article 902, paragraph 1). However, based on the Court's emphasis on giving effect to the policyholder's intent, legal commentary suggests it would be natural to conclude that such designated inheritance shares (as per a will) should then determine the proportions of the insurance proceeds. While this might increase the administrative burden on the insurer to ascertain the terms of a will, heirs would have a strong incentive to present the will to the insurer. If an insurer mistakenly paid out according to statutory shares when a will dictated different proportions, its payment might still be protected under the rules for payment made to a "quasi-possessor of a claim" (Civil Code Article 478).

Significance of the Ruling

The Supreme Court's July 18, 1994, decision was a landmark for several reasons:

- It established a clear default rule in Japanese law: when a life insurance policyholder designates "heirs" as beneficiaries, the proceeds are to be divided among those heirs according to their statutory inheritance shares, unless special circumstances clearly indicate a different intention.

- It prioritized the presumed reasonable intent of the policyholder for an equitable distribution of insurance benefits among their family members, consistent with general principles of inheritance.

- It resolved a significant point of contention and uncertainty that had existed in Japanese insurance and inheritance law regarding the division of insurance proceeds among multiple heir-beneficiaries.

Concluding Thoughts

The 1994 Supreme Court decision brings a practical, rational, and equitable interpretation to a common beneficiary designation in life insurance policies. By linking a designation of "heirs" to the division by statutory inheritance shares, the Court aligned insurance payouts with the likely intentions of policyholders—namely, to provide for their families in a manner consistent with established principles of familial entitlement. This approach particularly ensures a fairer distribution for close family members, such as a surviving spouse, who typically hold larger statutory inheritance shares and often have greater financial needs following the loss of the insured. The ruling reinforces the protective function of life insurance within the broader framework of family succession.