Shareholders Calling the Shots? Appointing the Representative Director in Japanese Non-Public Companies

Case: Appeal against a High Court decision dismissing an appeal against a District Court's dismissal of an application for a provisional disposition order for suspension of duties and appointment of a provisional agent.

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, Decision of February 21, 2017

Case Number: (Kyo) No. 24 of 2016

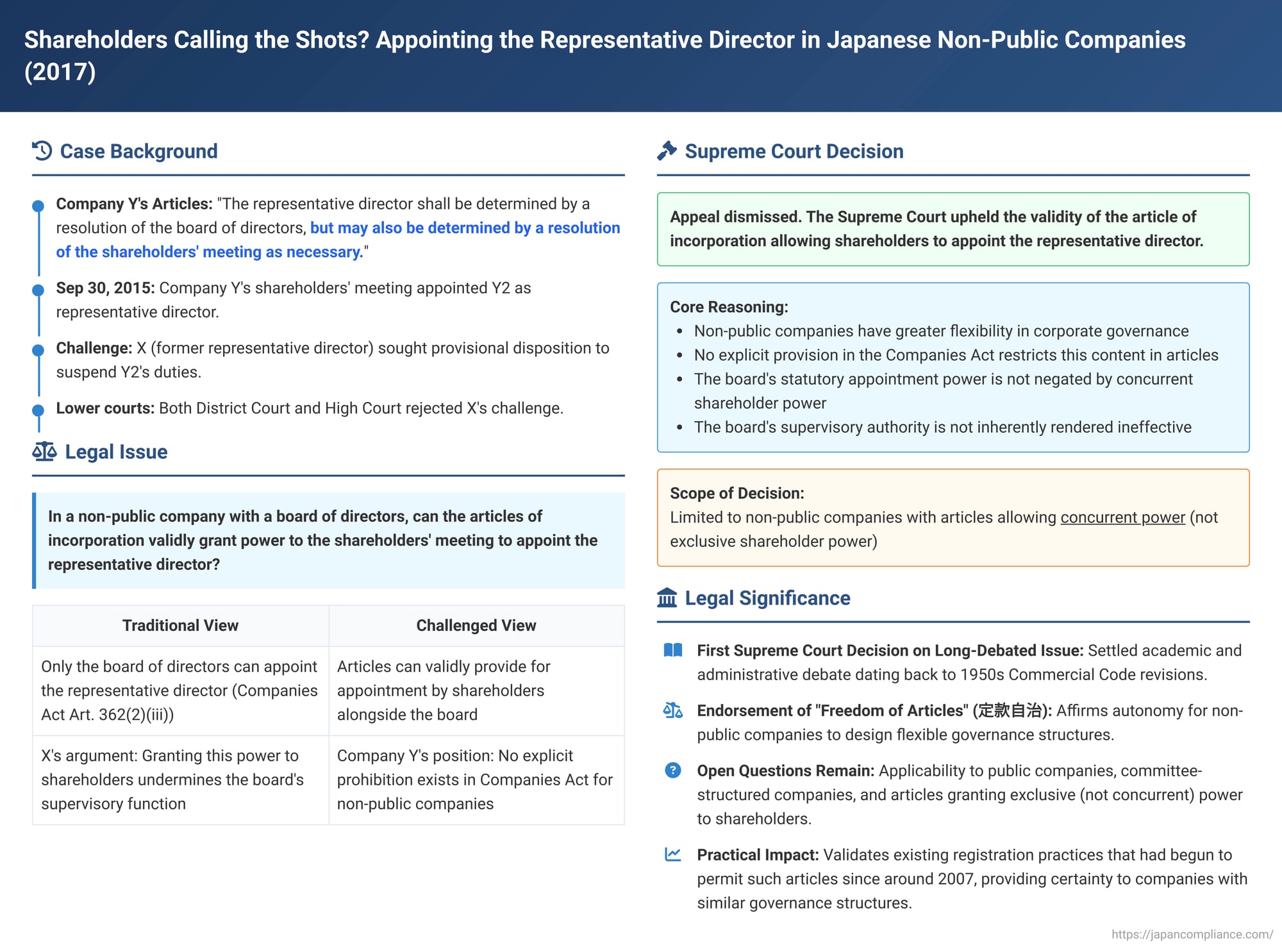

In a typical company with a board of directors, the board holds the statutory power to appoint and dismiss the representative director (often the CEO or President). However, can a company's articles of incorporation—its foundational internal rules—grant this significant power to the shareholders' meeting as well, particularly in a non-public company that has chosen to establish a board? This question, long debated in Japanese corporate law circles, was finally addressed by the Supreme Court in a decision on February 21, 2017, which affirmed the validity of such an arrangement under specific conditions.

The Board, the Shareholders, and the CEO: Facts of the Case

The case involved Company Y, a non-public company (a company whose shares are not publicly traded and typically have transfer restrictions) that had a board of directors. Company Y's articles of incorporation contained a notable provision regarding the appointment of its representative director: "The representative director shall be determined by a resolution of the board of directors, but may also be determined by a resolution of the shareholders' meeting as necessary." This created a system of concurrent power, where both the board and the shareholders' meeting could potentially appoint the company's top executive.

On September 30, 2015, Company Y held its ordinary general shareholders' meeting. At this meeting, a resolution was passed appointing Y2 as the company's representative director.

X, who had been the representative director of Company Y until this point, challenged this shareholders' meeting resolution. X alleged that the resolution was invalid due to legal violations and sought a provisional disposition (an interim court order) from the Chiba District Court (Kisarazu Branch) to suspend Y2's duties as representative director and to appoint a provisional agent to manage the company's affairs.

The Legal Challenge: Can Articles of Incorporation Grant CEO Appointment Power to Shareholders?

In the initial court proceedings, the validity of the specific article of incorporation allowing shareholder appointment of the representative director was not the central point of contention; the dispute revolved more around issues like the recognition of certain shareholders and the overall validity of the company's articles.

However, when X appealed to the Tokyo High Court, the argument shifted. X contended that the article of incorporation itself was invalid. The reasoning proffered was that allowing the shareholders' meeting to appoint the representative director would inherently weaken the board of directors' crucial function of supervising that representative director. The High Court was not persuaded by this argument. It dismissed X's appeal, stating that granting the shareholders' meeting the authority to appoint and dismiss the representative director does not automatically strip the board of its supervisory powers. X then sought and was granted permission to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Green Light: Upholding Shareholder Prerogative in Non-Public Companies

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision and, more importantly, affirming the validity of Company Y's article of incorporation that allowed for the appointment of the representative director by a shareholders' meeting resolution, in addition to by a board resolution.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Balancing Board Functions with Shareholder Autonomy

The Supreme Court's reasoning was concise but impactful:

- Flexibility for Non-Public Companies: The Court began by noting that non-public companies, such as Company Y, are not automatically required by the Companies Act to establish a board of directors (referencing Article 327, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Companies Act). If such a company voluntarily chooses to have a board, its shareholders' meeting retains the power to pass resolutions on matters stipulated in the Companies Act itself and on any other matters specifically provided for in the company's articles of incorporation (as per Article 295, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act).

- No Explicit Prohibition: The Supreme Court emphasized that the Companies Act contains no explicit provision that restricts the content of matters that can be so stipulated in the articles of incorporation, at least in this particular context for non-public companies with a board.

- Board's Supervisory Role and Appointment Powers Remain: The Court acknowledged that the Companies Act generally positions the board of directors as the organ responsible for supervising the representative director's execution of duties. However, it found that allowing a non-public company with a board to also determine its representative director by a shareholders' meeting resolution (in addition to by a board resolution) does not negate the board's own statutory power to appoint and dismiss the representative director, as provided for in Article 362, Paragraph 2, Item 3 of the Companies Act. Both bodies can hold this power concurrently.

- Supervisory Effectiveness Not Fatally Undermined: Crucially, the Court concluded that such an arrangement – where shareholders can also appoint the representative director – does not inherently render the board's overall supervisory authority ineffective.

Based on these points, the Supreme Court held that an article of incorporation in a non-public company with a board of directors, which permits the representative director to be appointed by a resolution of the shareholders' meeting in addition to by a resolution of the board of directors, is valid.

Analysis and Implications: Navigating a Long-Debated Terrain

This 2017 Supreme Court decision is highly significant as it was the first time Japan's highest court ruled on this specific, long-standing issue in corporate law. Previously, the matter was primarily a subject of academic debate and varying administrative interpretations.

- Historical Context and Pre-Companies Act (2005) Era:

The question first emerged in earnest with the 1950 revision of the Commercial Code, which made a board of directors a mandatory organ for stock companies and, in doing so, limited the previously near-omnipotent powers of the shareholders' meeting. Under that regime, the representative director was to be appointed by the board. Early administrative guidance for company registration, issued in a 1951 circular by the Director-General of the Civil Affairs Bureau, did not recognize articles of incorporation that allowed shareholders to appoint the representative director in a board-installing company.

Academic opinion was divided. The "invalidity view" argued that allowing shareholders to appoint the representative director would fatally undermine the board's ability to supervise that individual and could create confusing dual lines of authority and responsibility within the company. Conversely, the "validity view" contended that the board's supervisory function wouldn't be entirely lost, as the board could, for instance, still convene a shareholders' meeting to seek the representative director's dismissal if necessary. It's worth noting that much of this early debate revolved around articles that would grant exclusive appointment power to shareholders, rather than the "concurrent power" model seen in the 2017 Supreme Court case. - The 2005 Companies Act and Shifting Interpretations:

The enactment of the Companies Act in 2005 changed the landscape. It established companies without a board of directors as the default model and made the installation of a board largely optional for non-public companies (with some exceptions). This signaled a move towards greater flexibility in corporate structuring.

Interestingly, an initial administrative circular issued by the Ministry of Justice in March 2006, just before the Companies Act came into effect, seemed to maintain the older, more restrictive stance on shareholder appointment of representative directors. However, within about a year, company registration practice began to shift towards accepting articles of incorporation that allowed for such "concurrent power." This change was likely influenced by the published views of some of the key drafters of the Companies Act, who suggested that while articles granting exclusive appointment power to shareholders might be problematic, "concurrent power" articles could be permissible.

The commentary also points to some potential internal inconsistencies in the drafters' overall views when considering general limitations on what articles of incorporation can stipulate in relation to the Companies Act (specifically concerning Article 29, which states that articles must not violate the Act). Furthermore, the wording of Article 349, Paragraph 3 of the Companies Act—which explicitly allows shareholders to appoint the representative director in companies without a board of directors (the parenthetical expression states "excluding companies with a board of directors")—could have been interpreted as implicitly prohibiting shareholder appointment in board-installing companies. This Supreme Court decision effectively clarifies that such an interpretation is not correct for concurrent power articles in non-public companies. - The Supreme Court's Concise Reasoning:

Compared to the long and complex history of the debate, the Supreme Court's reasoning in this decision was notably succinct. It hinged on two main points: first, the absence of any explicit statutory provision in Article 295, Paragraph 2 (regarding shareholder resolution matters) that would restrict articles from granting this concurrent power; and second, the finding that the board's own statutory appointment and dismissal powers (under Article 362, Paragraph 2, Item 3), along with its overall supervisory effectiveness, are not nullified by such a concurrent arrangement. - Critiques and Ongoing Discussion:

Some legal commentators have questioned the breadth of the Court's assertion that the board's supervisory effectiveness is not undermined. In theory, particularly in companies where procedures for convening shareholder meetings can be streamlined (e.g., through unanimous consent of shareholders for a de facto fully attended meeting), a representative director could potentially be replaced by shareholders without the board's prior knowledge or involvement. However, it is argued that this is more a characteristic of the inherent power of shareholder meetings in such companies rather than a fatal flaw specific to this type of article of incorporation. - The "Shatei" (Scope and Reach) of the Decision:

A crucial aspect of analyzing any Supreme Court decision is its shatei – its scope and the extent to which its reasoning applies to different factual scenarios.- Limited to Non-Public Companies with Concurrent Power Articles: The decision is explicitly framed around "a non-public company with a board of directors" and an article of incorporation that allows appointment by shareholders "in addition to" the board (i.e., concurrent power).

- Public Companies: Would this reasoning apply to public companies (where a board is generally mandatory)? Some scholars argue it could, as the core reasoning about the board's powers not being negated might still hold. Others suggest a different policy consideration applies to public companies, potentially leading to a different outcome. Historical academic views often distinguished between public and non-public companies on this issue, being more restrictive for public companies.

- "Exclusive Power" Articles: What if the articles attempted to give exclusive power to the shareholders' meeting to appoint the representative director, completely removing this function from the board? Most commentators believe the Supreme Court's reasoning would not extend to validate such an arrangement, as it would directly contradict and undermine the board's statutory powers outlined in Article 362, Paragraph 2, Item 3.

- Dismissal/Removal by Shareholders: The decision specifically addresses "appointment" (sentei). Does it also validate articles allowing shareholders to dismiss (kaishoku) the representative director? While not explicitly stated, the prevailing view among commentators is that it likely does. It would be difficult to persuasively argue for allowing shareholder appointment but not shareholder dismissal, especially since shareholders already have the power to remove any director from their position (which would, by extension, remove them as representative director). The logic concerning the board's retained supervisory powers would seem to apply similarly.

- Companies with Special Governance Structures: The applicability of this decision to companies with more complex, statutorily defined governance structures, such as those with nomination committees or audit and supervisory committees, remains a subject of discussion. Some argue that the specific legislative intent behind these structures might lead to a different conclusion (i.e., invalidity of such articles).

Ultimately, the decision reflects the Companies Act's broader theme of allowing greater "freedom of articles" (teikan jichi) – autonomy for companies to design their internal governance structures, particularly for non-public entities – balanced against the fundamental roles and responsibilities assigned to corporate organs by statute.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's February 21, 2017, decision provides important validation for non-public companies in Japan that wish to adopt a more flexible approach to appointing their representative director. By confirming that articles of incorporation can validly grant concurrent appointment power to both the board of directors and the shareholders' meeting, the Court has acknowledged the desire for potentially greater shareholder involvement in leadership selection in such companies. This ruling underscores that the board's statutory role, including its power to appoint and supervise the representative director, is not necessarily undermined when this authority is shared with the shareholders. However, the decision is carefully circumscribed, and its applicability to public companies or to articles that attempt to grant exclusive appointment power to shareholders remains open to further legal interpretation and debate.