Shareholder Unanimity vs. Formal Rules: A Japanese Supreme Court Look at Conflict-of-Interest Deals and Share Transfer Validity

Case: Action for Dissolution of a Company

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of September 26, 1974

Case Number: (O) No. 1225 of 1972

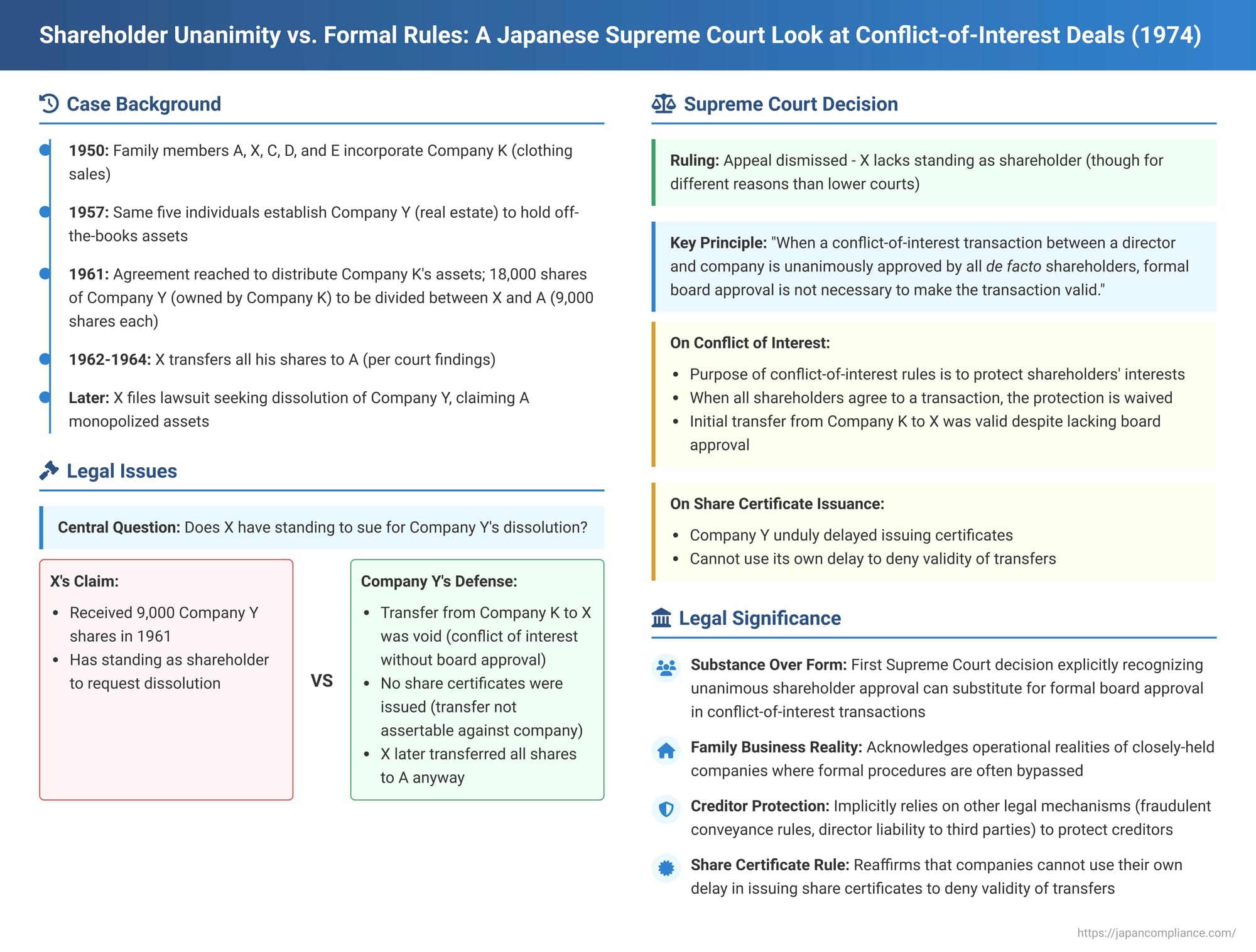

Japanese company law typically requires formal approval from the board of directors for transactions where a director's personal interests might conflict with those of the company. This rule aims to protect the company and its shareholders from potential self-dealing. However, what happens if such formal board approval is missing, but all the company's shareholders unanimously agree to the transaction? And what is the status of share transfers when a company has unduly delayed issuing physical share certificates? A significant Supreme Court decision on September 26, 1974, addressed these questions, particularly in the context of closely-held family businesses, emphasizing substance over strict formality in certain situations.

A Family Feud and Disputed Shares: Facts of the Case

The dispute originated from a family-run enterprise. Company K, a clothing sales business, was initially operated by A (X's brother) and B (X's sister). In 1950, it was incorporated. The key individuals involved in its management and who were its de facto shareholders were A, the plaintiff X, X's other brother C, X's brother-in-law D (husband of another sister), and B's husband E. These five individuals jointly managed Company K.

In 1957, these same five individuals established Company Y, a real estate company, with the purpose of holding and growing certain off-the-books assets belonging to Company K. Again, these five individuals were the effective owners and controllers of Company Y.

In 1961, a critical agreement was reached among these five individuals (A, X, C, D, and E) to distribute the assets of Company K and its affiliated entities among themselves. A key part of this agreement was that 18,000 shares of Company Y, which were legally owned by Company K, were to be divided: 9,000 shares would go to X, and the other 9,000 shares to A.

Subsequently, however, disagreements and conflicts erupted among these five individuals concerning the implementation of this asset distribution plan.

This led X to file a lawsuit seeking the court-ordered dissolution of Company Y. X alleged that his brother A was attempting to monopolize Company Y's assets, improperly disposing of its real estate, and thereby causing Company Y's business operations to grind to a halt and suffer irreparable damage. Such circumstances could be grounds for judicial dissolution under the then-Commercial Code (Article 406-2, Paragraph 1, similar in substance to Article 833, Paragraph 1 of the current Companies Act).

Company Y, in its defense, challenged X's legal standing to bring the dissolution suit, arguing that X was not, in fact, a shareholder of Company Y. This argument was based on two main points concerning the validity of the initial transfer of Company Y shares from Company K to X:

- Conflict of Interest: At the time of the purported transfer of Company Y shares from Company K to X, X was a director of Company K. Under the then-Commercial Code Article 265 (which governed conflict-of-interest transactions between a director and their company, analogous to current Companies Act Article 356, Paragraph 1, Item 2 and Article 365, Paragraph 1), such a transaction required the approval of Company K's board of directors. Company Y asserted that this board approval was never obtained, rendering the share transfer to X void.

- Non-Issuance of Share Certificates: Company Y had never actually issued physical share certificates. According to the then-Commercial Code Article 204, Paragraph 2 (similar to current Companies Act Article 128, Paragraph 2), a transfer of shares made before the issuance of share certificates could not be asserted against the company. Thus, Company Y argued that the transfer from Company K to X was ineffective against Company Y.

Lower Courts' Dismissal

Both the Tokyo District Court (judgment dated August 1, 1970) and the Tokyo High Court (judgment dated August 10, 1972) dismissed X's lawsuit. They found that X lacked the necessary standing as a shareholder of Company Y to sue for its dissolution, although their specific reasons for this conclusion differed. X appealed this outcome to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Standing Denied, but Key Principles Affirmed

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, ultimately agreeing that X lacked standing. However, its reasoning on the validity of the share transfers involved important legal principles.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Substance Over Form in Shareholder Protection

The Supreme Court's judgment meticulously addressed the issues:

- X's Subsequent Transfer of Shares (Factual Finding): The Court first upheld the High Court's factual finding that, while X had indeed initially received 9,000 shares of Company Y from Company K as per the 1961 agreement, X had subsequently transferred all of these shares to his brother A (2,000 shares in 1962, and the remaining 7,000 shares in August 1964). This factual determination alone was sufficient to conclude that X was no longer a shareholder of Company Y at the time he filed the dissolution suit and therefore lacked standing.

However, the Supreme Court went on to address the legal validity of the initial transfer from Company K to X, as this had been a major point of contention and involved important principles of company law.

- Validity of the Company K-to-X Share Transfer (Conflict-of-Interest Issue):

- Purpose of Conflict-of-Interest Rules: The Court began by explaining the legislative intent behind the then-Commercial Code Article 265. This provision, requiring board approval for transactions between a director and their company, aims to prevent directors from abusing their position to pursue their own interests or those of third parties at the expense of the company, and by extension, its shareholders.

- Effect of Unanimous Shareholder Agreement: The Supreme Court then highlighted a crucial fact established by the High Court: the transfer of Company Y shares from Company K to X was carried out based on the unanimous agreement of all of Company K's de facto shareholders (namely, the five individuals: A, X, C, D, and E).

- Board Approval Deemed Unnecessary in this Context: Given this unanimous agreement among all effective shareholders, the Supreme Court ruled that separate, formal approval by Company K's board of directors was not necessary. To invalidate the transfer for lack of board approval, when all the individuals whose interests the rule is designed to protect had consented, would contradict the very purpose of the conflict-of-interest legislation. Therefore, the transfer from Company K to X was deemed valid despite the absence of a formal board resolution.

- Validity of Pre-Certificate Share Transfer:

- The Court acknowledged that Company Y had not issued physical share certificates, meaning the transfers in question (from Company K to X, and subsequently from X to A) were, technically, transfers made before the issuance of certificates.

- However, the Supreme Court found that, based on the factual circumstances, Company Y was unduly delaying the issuance of these share certificates.

- Affirming a prior Grand Bench precedent (Supreme Court judgment of November 8, 1972), the Court held that a company cannot rely on its own undue delay in issuing share certificates as a basis to deny the validity of share transfers made before their issuance. Therefore, the transfers were also considered effective from this perspective.

- Rejection of the Lower Court's "Partnership" Characterization:

The Supreme Court took issue with a part of the High Court's reasoning which had suggested that Company K and Company Y, given their origins and management by a small group of family members, were essentially partnerships (kumiai under the Civil Code) rather than true corporations, and therefore, strict company law provisions might not apply. The Supreme Court cautioned that the "denial of corporate personality" (法人格否認 - hōjinkaku hinin) is an exceptional legal remedy that should be applied sparingly and only in specific circumstances (such as when the corporate form is a mere shell or is abused to evade the law). The facts found by the High Court were deemed insufficient to warrant such a denial for Company K and Company Y. However, this critique of the High Court's reasoning did not alter the final outcome regarding X's lack of standing. - Ultimate Conclusion on Plaintiff's Standing:

Since both the initial transfer of Company Y shares from Company K to X, and the subsequent transfer of those shares from X to A, were deemed valid by the Supreme Court, it followed that X was no longer a shareholder of Company Y when he initiated the dissolution lawsuit. Consequently, he lacked the legal standing to bring such an action, and his suit was correctly dismissed as improper.

Analysis and Implications: Prioritizing Shareholder Will in Closely-Held Companies

This 1974 Supreme Court judgment is highly significant, particularly for its pronouncements on conflict-of-interest transactions in closely-held companies.

- Unanimous Shareholder Agreement as a Substitute for Board Approval:

The most impactful aspect of this ruling is its clear statement that unanimous agreement among all de facto shareholders can validate a conflict-of-interest transaction between a director and the company, even if formal board of directors' approval is lacking. This was the first Supreme Court decision to explicitly establish this principle.

The rationale is deeply rooted in the purpose of the conflict-of-interest rules (now found in Articles 356 and 365 of the Companies Act). These rules are designed to protect the company from harm that might arise when a director's personal interests diverge from the company's interests. The ultimate beneficiaries of this protection are the shareholders. If all shareholders consent to a transaction, they are, in effect, waiving this protection, and there is no remaining interest within the company that the rule needs to shield in that specific instance.

This principle is particularly relevant for closely-held and family-owned companies, where corporate formalities like regular board meetings are often dispensed with, and significant decisions are frequently made by informal consensus among the owner-managers. This ruling prevents a party in a subsequent dispute from opportunistically using the lack of a formal board resolution to invalidate a transaction that everyone involved had previously agreed to. The facts of this case, arising from a dispute within a family business, perfectly illustrate such a scenario. This decision is also consistent with an earlier 1970 Supreme Court case which found board approval unnecessary for a transaction between a one-person company and its sole shareholder-director, emphasizing the lack of actual conflict when the director and the totality of shareholder interests align. - Theoretical Basis for the Principle:

Legal scholars have offered various theoretical underpinnings for this outcome. One view is that when all shareholders agree, there is no substantive conflict of interest to regulate, similar to the situation in a one-person company. Another perspective suggests that unanimous shareholder agreement could be constructively interpreted as a de facto shareholder resolution that both amends the articles of incorporation to allow shareholder approval of such transactions (as permitted by Companies Act Article 295, Paragraph 2) and then approves the specific transaction. However, with the current Companies Act Article 319 requiring written or electronic consent for a resolution to be deemed passed by unanimous shareholder agreement without a meeting, this constructive interpretation faces more formal hurdles if such records are absent. - Concerns Regarding Creditors and Subsequent Shareholders:

A common critique of this principle is the potential impact on company creditors or individuals who become shareholders after such a unanimously agreed but formally unapproved transaction has occurred.

However, the prevailing response in legal commentary is that other legal mechanisms sufficiently protect these parties:- Subsequent Shareholders: Typically acquire their shares at a price reflecting the company's financial condition after the transaction in question. If not, they may have remedies against the seller of the shares under general contract law principles (e.g., for misrepresentation or breach of warranty).

- Company Creditors: The protection afforded to creditors by the board approval requirement for conflict-of-interest transactions is indirect at best; even a board-approved transaction can be detrimental to creditors if it's a poor business deal for the company. Creditors have more direct remedies, including:

- Holding directors liable to third parties for willful misconduct or gross negligence in the performance of their duties (Companies Act Article 429, Paragraph 1). This liability may persist even if the directors' liability to the company itself was waived by unanimous shareholder consent (under Companies Act Article 424).

- Actions to set aside fraudulent conveyances (under Civil Code Article 424).

- A bankruptcy trustee's power to avoid certain pre-bankruptcy transactions.

Given these alternative avenues for creditor protection, and the indirect nature of the conflict-of-interest rules in safeguarding creditor interests, the argument is that there is no compelling need to allow creditors to interfere with transactions unanimously approved by all shareholders by asserting the lack of formal board approval.

- Who Can Assert Invalidity of a Conflict-of-Interest Transaction?

Generally, only the company itself (acting through its proper organs) can assert the invalidity or voidability of a conflict-of-interest transaction that lacked proper approval. The director involved in the conflict or the other party to the transaction typically cannot. In this case, Company Y (a third party to the K-X transaction) was attempting to argue the invalidity of that transaction to undermine X's shareholder status in Y. Most legal commentators on this case suggest that Company Y likely lacked the legal standing to make such an assertion regarding the K-X deal on conflict-of-interest grounds. - Share Transfers Before Certificate Issuance:

The Supreme Court also importantly reaffirmed its existing precedent that a company which has unduly delayed issuing share certificates cannot then use the non-issuance of certificates as a shield to deny the validity of share transfers effected before their issuance. This protects the liquidity of shares and the rights of transferees when a company fails in its obligation to provide certificates in a timely manner.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision of September 26, 1974, delivers a nuanced message, particularly significant for closely-held corporations. It champions the substantive will of the company's ultimate owners – the shareholders – by recognizing that their unanimous agreement to a conflict-of-interest transaction can cure the absence of formal board approval. This pragmatic approach acknowledges the operational realities of many smaller companies while ensuring that the core purpose of conflict-of-interest rules (protecting shareholders) is not undermined when those very shareholders collectively consent. The ruling also reinforces the protection for shareholders involved in transfers of uncertificated shares when a company unreasonably delays issuing the certificates. While the plaintiff in this specific case ultimately failed due to having already transferred his shares, the legal principles articulated by the Supreme Court continue to resonate in Japanese corporate law.