Shareholder Access to Corporate Records: A Deep Dive into a Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Decision

Judgment Date: July 1, 2004

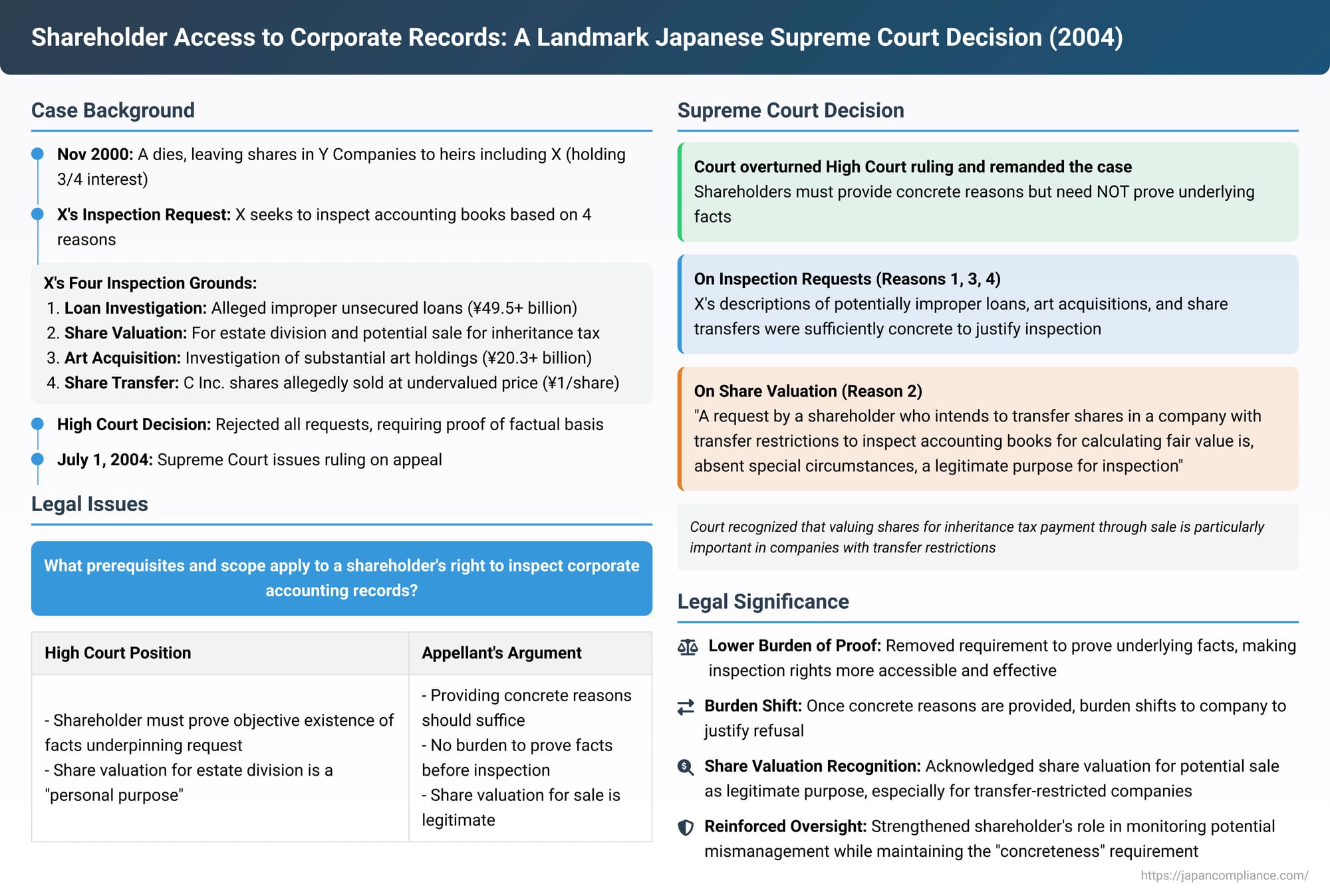

The ability of shareholders to access and inspect corporate accounting books and records is a cornerstone of corporate governance, serving as a vital tool for transparency and accountability. This article explores a significant judgment by the Supreme Court of Japan, dated July 1, 2004, which clarified crucial aspects of a shareholder's right to inspect such records. This case, formally known as the "Accounting Book Inspection and Copying, Shareholder General Meeting Minutes, etc. Inspection and Copying, Employee General Meeting Minutes, etc. Inspection and Copying Request Case" (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, Case No. 2003 (Ju) No. 1104), offers important insights into the prerequisites and scope of these shareholder rights.

Factual Background of the Dispute

The case involved an appellant, X, who was a legal heir of A. Upon A's death on November 15, 2000, A held substantial shares and equity interests (collectively, "the Shares") in a group of companies, referred to here as Y1, Y2, Y3, Y4, Y5, and Y6 (collectively, "the Y Companies"). Y1 was a limited liability company, while the other Y Companies were stock corporations (kabushiki gaisha) whose articles of incorporation stipulated that transfers of shares required approval from the board of directors.

Following A's death, the Shares became part of A's estate, subject to quasi-co-ownership by four legal heirs, including X. X held a three-fourths quasi-co-ownership interest in these Shares. Furthermore, X notified the Y Companies that she had been designated by the co-heirs as the person to exercise the shareholder or member rights associated with the Shares.

X sought to inspect and copy the accounting books and other specified records of the Y Companies. Her request was based on several grounds, which she detailed in writing:

- Reason [1]: Investigation of Loans (the "Loan Investigation Need")

X alleged that C Inc., a company belonging to the "B Group," had received substantial unsecured loans from several of the Y Companies: ¥31.772 billion from Y2, ¥9.95 billion from Y1, ¥7.12 billion from Y6, and ¥700 million from Y4 (collectively, "the Loans"). X further stated that C Inc.'s financial condition deteriorated after it extended an unsecured loan of ¥7.24775 billion on September 17, 2001, to D, who was the representative director of Y2. This, X argued, created a risk that the Y Companies would be unable to recover the Loans. X contended that these Loans made by the four Y companies were illegal and improper, necessitating an inspection of their accounting books to enable her to exercise appropriate oversight. - Reason [2]: Valuation of Shares for Estate and Tax Purposes (the "Share Valuation Need")

X stated that she needed to determine the fair market value of the Shares she inherited. This valuation was for two primary purposes: firstly, for ongoing estate division discussions among the heirs, and secondly, in anticipation of a potential sale of the Shares to cover inheritance tax liabilities. - Reason [3]: Investigation of Art Acquisitions (the "Art Acquisition Investigation Need")

X pointed out that as of the fiscal year ending 2000, Y2 held art pieces with a book value of approximately ¥4.78 billion, and Y1 held art with a book value of approximately ¥15.49 billion (collectively, "the Artworks"). These Artworks were reportedly entrusted to E Foundation, an entity also part of the B Group. X argued that the acquisition of such substantial art holdings for non-business purposes could severely deplete the companies' assets, thereby risking irreparable harm to the companies and, consequently, to their shareholders and members. She sought to investigate the details of these acquisitions, including the nature, quantity, timing, purchase price, and sellers of the Artworks. - Reason [4]: Investigation of a Share Transfer (the "C Inc. Share Transfer Investigation Need")

X alleged that on December 11, 2000, Y1 sold its entire holding of 735,000 shares in C Inc. ("the C Inc. Shares") to D for a total price of ¥735,000 (i.e., ¥1 per share). X asserted that this sale was made at an unreasonably low price. She requested access to Y1's accounting records to investigate the accounting treatment of this share transfer and the original acquisition cost of the C Inc. Shares.

The Lower Court's Stance

The Tokyo High Court, the lower appellate court in this instance, dismissed X's requests. Its reasoning was twofold:

Firstly, the High Court laid down a general principle that for a shareholder or member to request inspection and copying of accounting books, they must specifically identify the target accounting records and concretely state the reasons for the request. Crucially, the High Court added that the shareholder must also demonstrate that the facts underpinning these stated reasons objectively exist.

Applying this to X's claims:

- Regarding Reason [1] (Loan Investigation) and Reason [3] (Art Acquisition), the High Court found that X had not objectively established the illegality of the loans or the art acquisitions. For Reason [1], it also suggested that it would be contrary to the principle of good faith for X, as an heir of A (who was purportedly deeply involved in the loans), to now claim their impropriety.

- Regarding Reason [4] (C Inc. Share Transfer), similarly, no objective evidence was found to support the claim of an illegal, low-price transfer.

- Therefore, these requests were deemed to fall under the statutory grounds for refusal—specifically, that the request was not made "for the purpose of conducting an investigation concerning the securing or exercise of the shareholder's rights" (as per then-Article 293-7, Item 1 of the Commercial Code, and Article 46 of the Limited Liability Company Act which applied this provision mutatis mutandis to limited liability companies).

Secondly, concerning Reason [2] (Share Valuation Need), the High Court interpreted X's purpose as primarily aimed at facilitating the estate division. It concluded that this was a purely personal objective, distinct from her status as a shareholder, and thus also fell under the aforementioned statutory refusal ground.

Dissatisfied with this outcome, X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Reversal and Reasoning

The Supreme Court of Japan overturned the High Court's decision, remanding the case for further proceedings. The Supreme Court's judgment provided critical clarifications on the requirements for shareholder inspection requests.

I. Concreteness of Reasons vs. Obligation to Prove Underlying Facts

The Supreme Court first addressed the general requirements for a shareholder's request to inspect accounting records. It affirmed that both the Commercial Code and the Limited Liability Company Act require a shareholder (holding the requisite percentage of voting rights – 3% for stock companies, 10% for limited liability companies) to submit a written request stating the reasons for seeking inspection.

The Court agreed that these stated reasons must be concrete. However, it decisively rejected the High Court's assertion that the shareholder must also prove the objective existence of the facts that form the basis of those reasons. The Supreme Court found no legal basis for imposing such an evidentiary burden on the shareholder at the stage of requesting inspection.

The Court then examined X's stated reasons:

- Reason [1] (Loan Investigation): The Supreme Court found X's description of the large, unsecured loans to C Inc. by four of the Y Companies, her assertion of their illegality or impropriety, and her stated need to investigate their timing, terms, and conditions, to be sufficiently concrete. There was no lack of specificity in this stated reason for requesting access to the relevant accounting books of the four Y companies.

- Reason [3] (Art Acquisition): Similarly, X's claim that the Y Companies' purchase of substantial artworks was illegal or improper, and her desire to investigate the timing, price, and counterparties of these purchases, were deemed concrete.

- Reason [4] (C Inc. Share Transfer): X's assertion that Y1 sold the C Inc. Shares to D at an unduly low price (¥1 per share) and her intent to investigate the accounting treatment and acquisition cost of these shares were also found to be concrete.

For these three reasons, the Supreme Court concluded that there were no circumstances indicating that the requests fell under the statutory refusal ground (i.e., being made for purposes other than investigating the securing or exercise of shareholder rights).

Regarding the High Court's point about A's alleged deep involvement in the loans, the Supreme Court stated that even if A had been involved, this fact alone would not immediately render X's request based on Reason [1] a violation of the principle of good faith.

Thus, the Supreme Court held that the High Court erred in law by denying these requests based on its incorrect interpretation of the requirements.

II. Valuation for Share Sale as a Legitimate Reason for Inspection

The Supreme Court then turned to Reason [2] (Share Valuation Need). It noted that, separate from the estate division aspect, X also cited the need to value the Shares in preparation for a potential sale to pay inheritance taxes. The Court found this reason, too, to be stated with sufficient concreteness.

The core of this part of the judgment addressed whether seeking to value shares for a prospective sale constitutes a legitimate purpose for inspecting accounting books, particularly in the context of companies with restrictions on share transfers.

The Court outlined the statutory framework under the Commercial Code and Limited Liability Company Act for shareholders in such companies who wish to transfer their shares:

- The shareholder must request the company's approval for the transfer to a specific party.

- If the company disapproves, the shareholder can demand that the company designate an alternative buyer.

- If the company disapproves and designates an alternative buyer, and if the shareholder and the designated buyer cannot agree on a price, either party can petition a court to determine the sale price.

The Supreme Court reasoned that for a shareholder to navigate these mandated procedures effectively—which include negotiating a price with a company-designated buyer—it is indispensable for the shareholder to be able to determine the fair value of their shares. Access to the company's accounting books, which reflect its financial condition and asset status, is crucial for such a valuation.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded:

"A request by a shareholder or member, who intends to transfer their shares or equity in a stock company or limited liability company that has restrictions on such transfers in its articles of incorporation, to inspect and copy accounting books for the purpose of appropriately dealing with the aforementioned procedures by calculating the fair value of said shares or equity, is, absent special circumstances, to be construed as being made for the purpose of conducting an investigation concerning the securing or exercise of shareholder or member rights, and does not fall under the refusal ground stipulated in [the then Commercial Code Art. 293-7] Item 1."

As there were no apparent "special circumstances" in X's case, her request based on Reason [2]—to value the Shares for a prospective sale—was deemed not to fall under the statutory refusal grounds. The High Court's contrary finding was also held to be an error in law.

The Supreme Court, therefore, quashed the parts of the High Court's judgment that were unfavorable to X and remanded the case to the High Court for further deliberation, specifically concerning the scope of the accounting books and records to which X should be granted access.

Analysis and Implications of the Supreme Court's Decision

This 2004 Supreme Court judgment has several important implications for shareholder rights in Japan:

- Lowering the Initial Hurdle for Inspection: No Need to Prove Underlying Facts

Perhaps the most significant aspect of this ruling is the clarification that while shareholders must provide concrete reasons for their inspection request, they are not required to prove the objective truth or existence of the facts underlying those reasons at the initial request stage.

The High Court's position would have created a "Catch-22" situation: shareholders often need access to the books precisely to find evidence of potential wrongdoing or to accurately assess a situation. Requiring them to prove the wrongdoing before getting access would effectively neuter the inspection right as an investigative tool.

The Supreme Court's stance acknowledges that the inspection right itself is a means of investigation. The "concreteness" requirement acts as a filter against vague or fishing expeditions, ensuring that the shareholder has a specific area of inquiry linked to their rights, rather than a general desire to browse company records. - Burden of Justifying Refusal Shifts to the Company

By removing the shareholder's burden to prove the underlying facts of their stated reasons, the practical effect is that once a shareholder presents concretely stated reasons that appear legitimate on their face, the onus shifts to the company. If the company wishes to refuse access, it must demonstrate that the request falls under one of the statutory grounds for refusal. These grounds typically include situations where the request is not for investigating matters related to the shareholder's rights, or where the request is abusive (e.g., intended to harass the company, harm its business for a competitor, or exert undue pressure).

The company cannot simply deny access by asserting that the shareholder's suspicions are unfounded; it must provide valid reasons for the denial based on the statutory exceptions. - Valuation for Share Transfer in Restricted-Share Companies Recognized as a Legitimate Purpose

The Court's explicit recognition that valuing shares for a sale is a legitimate reason for inspection, especially in companies with share transfer restrictions, is crucial. Shares in privately-held or closely-held companies (which often have such restrictions) are inherently illiquid. The statutory procedures for transfer (approval, designated buyer, court-determined price) are designed to balance the shareholder's desire to exit with the company's interest in controlling its ownership.

For these procedures to be meaningful, the shareholder must have a basis for assessing the shares' value. Without access to financial information, a shareholder would be at a significant disadvantage when negotiating a price with a company-designated buyer or when presenting a case for valuation to a court. The Supreme Court acknowledged this practical necessity. This is particularly relevant given that a significant number of Japanese companies, especially smaller and medium-sized enterprises, are structured as stock companies with share transfer restrictions. - Affirmation of Shareholder Oversight for Potential Mismanagement

The Court's acceptance of X's reasons concerning potentially improper loans, excessive art acquisitions, and an undervalued share sale as "concrete" reinforces the role of shareholders in monitoring corporate conduct. The reasons X provided pointed to specific transactions or asset holdings and articulated a concern that these actions were detrimental to the company and its shareholders. The right to inspect allows shareholders to scrutinize such decisions.

The fact that the Supreme Court found these reasons sufficiently concrete without demanding upfront proof of actual illegality underscores that the purpose of the inspection is, in part, to ascertain whether such illegality or impropriety exists. - The "Concreteness" Requirement as a Key Standard

While lowering the bar by removing the need to prove underlying facts, the Supreme Court maintained the requirement for "concrete" reasons. This means a shareholder cannot simply state a vague suspicion of mismanagement. They must identify, with a reasonable degree of specificity, the transactions, activities, or corporate affairs they wish to investigate and why these matters are relevant to their rights or interests as shareholders. For example, instead of saying "I suspect financial irregularities," a more concrete reason would be, "I seek to investigate the terms and justification for the large unsecured loan made to C Inc. on [date] as reported in [source], as this may have impaired the company's assets." X's reasons met this standard. - Estate Division vs. Sale for Inheritance Tax

It's interesting to note the Court's subtle distinction regarding X's Reason [2]. While the High Court focused on the "estate division" aspect as purely personal, the Supreme Court acknowledged the "sale for inheritance tax" component as a valid basis for valuation, tying it into the broader principle of needing to value shares for a potential sale under transfer restriction rules. While the judgment doesn't explicitly state that valuation purely for estate division would always be insufficient, its focus on the share sale mechanism (and the associated statutory procedures) provides a stronger, more company-law-centric justification for the inspection right. - Scope of Inspection Remains for Further Determination

The Supreme Court remanded the case for the High Court to determine the scope of the accounting books to be made available. This is a standard step. Even if a right to inspect is established, it doesn't automatically mean unrestricted access to all company records. The inspection granted is typically limited to those records relevant to the concretely stated reasons. The High Court would need to define this scope.

Conclusion

The July 1, 2004, Supreme Court judgment significantly clarified the landscape for shareholder inspection rights in Japan. By emphasizing that shareholders need to provide concrete reasons but do not bear the burden of proving the underlying facts of those reasons at the request stage, the Court has made the right of inspection a more accessible and effective tool. Furthermore, its recognition of the necessity for shareholders in companies with transfer-restricted shares to value their holdings for potential sale—and to access accounting books for this purpose—addresses a critical practical need. This decision reinforces the principle that shareholder inspection rights are not merely a formality but a substantive entitlement crucial for both exercising individual shareholder rights and promoting broader corporate accountability. It strikes a balance, requiring shareholders to articulate specific concerns while preventing companies from stonewalling legitimate inquiries by demanding premature proof of a case that the inspection itself is designed to help build.