Shared Plan, Different Crimes: The 1979 Ruling on "Excess of Complicity"

Case: The Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Case No. 1978 (A) 2113

Decision Date: April 13, 1979

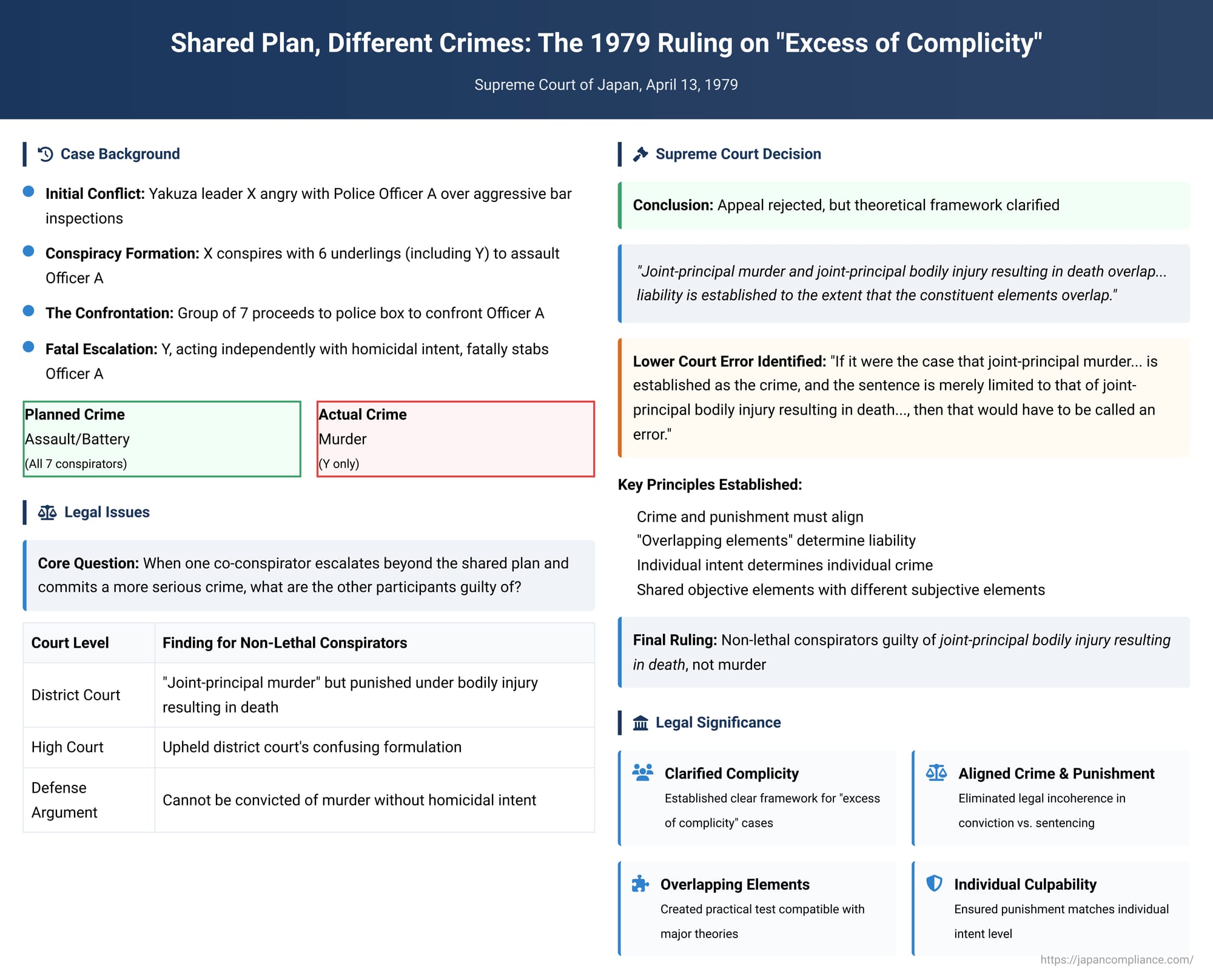

In a pivotal 1979 decision, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed a classic problem in criminal law: when a group conspires to commit a crime, but one member independently escalates the violence and commits a more serious offense, what crime are the other participants guilty of? The case, involving a yakuza gang's planned assault on a police officer that ended in murder, forced the Court to clarify the intricate relationship between shared intent, individual culpability, and the final name of the crime for which a person can be convicted.

The Facts: A Conspiracy of Assault Escalates to Murder

The defendant, X, was the leader of a yakuza affiliate. He became enraged with a police officer, A, who had conducted aggressive inspections of a stand bar that served as a source of income for the gang. X decided to retaliate. He conspired with six of his underlings, including a man named Y, to commit assault or battery against Officer A.

The group of seven proceeded to the local police box to confront A. During the ensuing altercation, X and his men shouted challenges and insults at the officer. In the heat of the moment, Y, one of the gang members, became particularly agitated by Officer A's response. Acting with at least conditional homicidal intent (miketsu no koi, a concept similar to "depraved-heart" or "conscious disregard for human life"), Y pulled out a concealed knife and fatally stabbed Officer A in the lower abdomen. The other six conspirators, including the leader X, had only planned and intended to commit assault or battery; they did not share Y's intent to kill.

The central legal question was clear: While Y was undoubtedly guilty of murder, what was the criminal liability of X and the other five members who had participated in the joint enterprise but did not intend for it to become lethal?

The Lower Courts' Ambiguous Formulation

The trial court (the Kobe District Court) navigated this complex issue with wording that created its own legal controversy. It stated that the actions of the six non-lethal participants "correspond to Article 60 (Joint Principals) and Article 199 (Homicide) of the Penal Code," but because their intent was only for assault or injury, "pursuant to Article 38(2) [Mistake of Fact], they should be punished under the penalty for... Bodily Injury Resulting in Death (Article 205)."

The Osaka High Court upheld this ruling. However, the formulation was deeply problematic. It appeared to find the defendants guilty of one crime (joint-principal murder) but then sentence them for a different, lesser crime (joint-principal bodily injury resulting in death). On appeal to the Supreme Court, X's defense lawyer argued that this was legally incoherent. The law, he contended, should not permit a conviction for a crime whose essential mental element—homicidal intent—was admittedly absent. Instead, the law should be interpreted to mean that the more serious crime of murder was never established for them in the first place.

The Supreme Court's Clarification: Crime and Punishment Must Align

The Supreme Court of Japan ultimately rejected the appeal, but in doing so, it sided with the defense on the core theoretical point and clarified the law for all future cases. It held that the non-homicidal co-conspirators were guilty of joint-principal bodily injury resulting in death, not just punished under that statute.

The Court's reasoning was methodical:

- Shared Objective Elements: The Court first observed that the crimes of murder and bodily injury resulting in death are, from an objective standpoint, identical. Both involve an act that causes the death of a person. The only difference is the subjective mental state of the perpetrator—the presence or absence of "homicidal intent" (satsui).

- The "Overlapping Elements" Principle: Building on this observation, the Court laid down its determinative rule. In a case where a co-conspirator with only an intent to injure participates in an act that results in death, liability is established "to the extent that the constituent elements of joint-principal murder and joint-principal bodily injury resulting in death overlap." Since the non-lethal members intended an act of violence, and that act foreseeably resulted in death, their actions and intent perfectly match the elements of bodily injury resulting in death.

- Rejecting the "Guilty of X, Punished for Y" Theory: The Court explicitly validated the defense's central argument, stating that the lower court's approach, if interpreted literally, was wrong. It declared: "If it were the case that joint-principal murder... is established as the crime, and the sentence is merely limited to that of joint-principal bodily injury resulting in death..., then that would have to be called an error." The Court affirmed that because the six men lacked homicidal intent, "there is no reason for joint-principal murder to be established" for them.

- Reinterpreting the Lower Court's Judgment: Despite finding the lower court's legal theory to be flawed if taken at face value, the Supreme Court salvaged the conviction through a charitable interpretation. It concluded that when the lower court wrote that the defendants' actions "correspond to... Homicide," it was not actually finding them guilty of joint-principal murder. Rather, the lower court was simply acknowledging the objective factual outcome (a death occurred) before correctly applying the law to find them guilty of the lesser crime that matched their intent. Therefore, because the final conviction and sentence were substantively correct, there was no error in the judgment's conclusion.

The Theoretical Underpinnings: A Lingering Debate

While the Supreme Court’s decision provided a clear and practical solution, it left a deeper theoretical debate unresolved. The ruling is compatible with two major competing theories of complicity in Japanese law:

- The Partial Crime-Collective Theory (Bubunteki Hanzai Kyōdōsetsu): This theory holds that a joint crime can be established based on the "overlapping" or shared portion of the participants' intentions. In this case, all seven members shared the intent to commit at least an assault. This shared intent, combined with the resulting death, forms a "partial" collective crime of bodily injury resulting in death for all participants. The killer, Y, would additionally be liable for murder on his own. The Court’s "overlapping elements" language aligns very closely with this theory.

- The Act-Collective Theory (Kōi Kyōdōsetsu): A more modern and influential theory, this posits that complicity is about jointly performing a physical act, not necessarily sharing an intent for the same ultimate crime. Each participant is then judged for the crime that corresponds to their individual intent as applied to the joint act's outcome. This theory also reaches the same result: X and the others are guilty of bodily injury resulting in death, while Y is guilty of murder.

The 1979 decision did not explicitly endorse one theory over the other. By focusing on the practical outcome and the "overlapping elements," it created a rule that works under either theoretical framework, leaving the academic debate to continue.

Conclusion

The 1979 Supreme Court ruling was a landmark clarification in the law of complicity. It definitively established that in cases of "excess of complicity," co-conspirators are convicted of the crime that matches their own level of intent, not the more serious crime unexpectedly committed by their confederate. It corrected a long-standing and confusing practice by ensuring that the crime of conviction aligns with the defendant's actual culpability and the sentence imposed. This decision provides a clear, predictable, and just framework for handling one of the most common and complex scenarios in criminal law.